The four reinforcement contingencies are the most fundamental principles of behavior. Unfortunately, it can be difficult for students to differentiate between the contingencies and generalize that knowledge of contingencies to new examples (i.e., stimulus generalization or far transfer). Many students don’t think about the environmental events that affect their behavior and are unfamiliar with antecedents and consequences. While it may seem straightforward to teach the four reinforcement contingencies, there are many prerequisite skills that need to be established for students to truly understand the functions of behavior.

Before we discuss how to teach the contingencies, we’ll consider the basic definitions for the four reinforcement contingencies. A target response or behavior is the response class or instance of a response class (i.e., behaviors that serve a common function) selected for change.

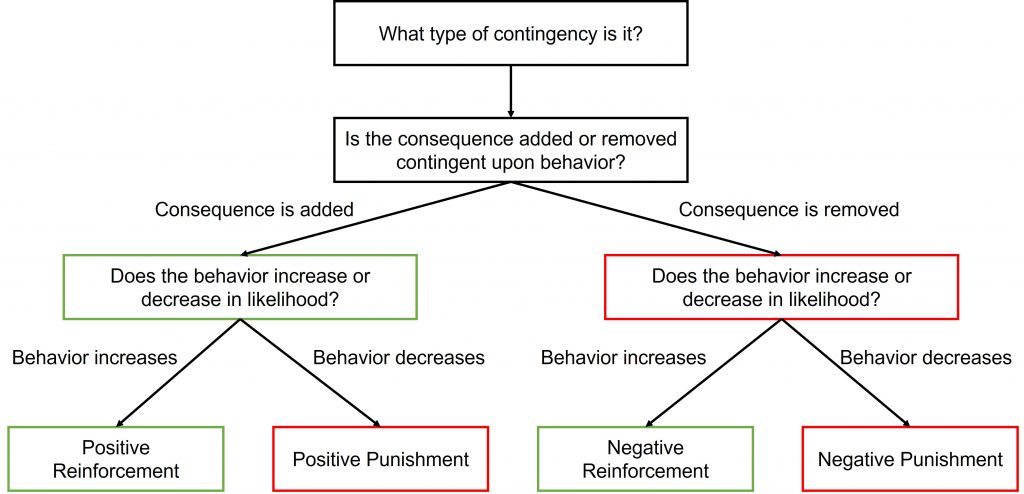

- In positive reinforcement, a stimulus or event is added or delivered after a target response occurs, and the target response is more likely to occur in the future.

- In negative reinforcement, a stimulus or event is removed (i.e., escape) or omitted (i.e., avoidance) after a target response occurs, and the target response is more likely to occur in the future. In applied settings, elopement could be maintained by escape from task demands (e.g., Boyle et al., 2017; Phillips et al., 2018).

- In positive punishment, a stimulus or event is added or delivered after a target response occurs, and the target response is less likely to occur in the future. In applied settings, contingent exercise (e.g., Gordon et al., 1986; Luce et al., 1980) and response blocking (e.g., Hagopian & Adelinis, 2001; McCord et al., 2005) are positive punishment procedures.

- In negative punishment, a stimulus or event is removed or omitted after a target response occurs, and the target response is less likely to occur in the future. In applied settings, planned ignoring is a negative punishment procedure (e.g., Codding et al., 2005; Hester et al., 2009).

If we’re assessing response rate, then we’ll see an increase in the rate of responding with positive and negative reinforcement. With positive and negative punishment procedures, we’ll see a decrease in the rate of responding after the contingency is in effect.

There are two additional types of positive reinforcement contingencies or if-then relations between behavior and its consequences. Extinction is a procedure in which a target response was previously reinforced but is now no longer reinforced (e.g., Iwata et al., 1994; Lerman et al., 1999). When no consequence is delivered, the target behavior will be less likely to occur in the future. Differential reinforcement is a procedure in which a target response is selected for reduction (e.g., Vollmer et al., 1999; Waters et al., 2009). With both extinction and differential reinforcement procedures, the target behavior was previously positively reinforced and will now decrease or extinguish entirely. There are four versions of differential reinforcement procedures: delivering the reinforcer when the target behavior doesn’t occur (i.e., differential reinforcement of other behavior), delivering the reinforcer when an alternative or other appropriate behavior occurs but not the target behavior (i.e., differential reinforcement of alternative behavior), delivering the reinforcer when a behavior that cannot be emitted at the same time as the target behavior occurs (i.e., differential reinforcement of incompatible behavior), and delivering the reinforcer when a target behavior occurs below a specified frequency (i.e., differential reinforcement of low rates of behavior). For these procedures, it’s best to think of positive reinforcement occurring in the natural environment in Phase 1 of an experiment for the inappropriate target behavior and extinction or differential reinforcement occurring in Phase 2.

For students to understand the reinforcement contingencies, they will need to understand some prerequisite concepts like operant behavior (e.g., Bouton & Balleine, 2019; Mechner et al., 1997), classical or Pavlovian or respondent conditioning (e.g., Lattal & Lattal, 2012; Rescorla, 1988), antecedent stimuli (e.g., Call et al., 2005; Catania, 2006), reinforcers and punishers, and aversive and appetitive stimuli. Reinforcers and punishers are not universal and are identified based on their effect on future behavior, but appetitive and aversive stimuli are defined prior to seeing their effect on behavior. Appetitive stimuli are those stimuli and activities that a person will work to obtain (e.g., Dimitropoulos et al., 2000; Silva & Timberlake, 1998). Aversive stimuli are those stimuli and activities that a person will work to avoid (see also Hineline, 1984; Moore & Edwards, 2013). That is, students need to be able to identify examples of behavior within a written description or from a video clip as well as understand how operant and respondent conditioning can create effective antecedents to and consequences of behavior. Diagramming written scenarios can help students practice identifying antecedents, behavior, and consequences.

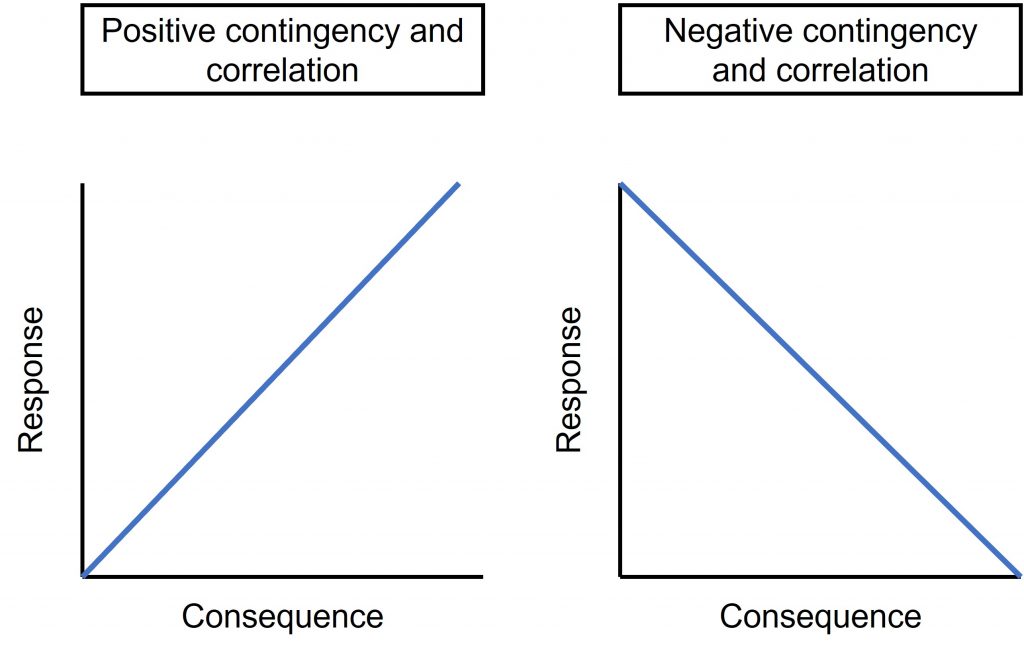

In behavior analysis, we refrain from making value-based judgments about behavior and its consequences (e.g., Ruiz & Roche, 2007). Instead, positive means add or deliver a consequence. Negative means subtract or remove/omit/cancel a scheduled consequence (see also Baron & Galizio, 2006). While it is true that rats will press a lever for food as an example of a positive reinforcement contingency (e.g., Wilkenfield et al., 1992) and press a lever to avoid shock as an example of a negative reinforcement contingency (e.g., Pear et al., 1978), rats will also press a lever for shock if that shock indicates that food will occur as an example of positive reinforcement (e.g., Everly & Perone, 2012; Holz & Azrin, 1961) and press a lever less frequently for a devalued reinforcer even within a positive reinforcement contingency (e.g., Adams & Dickinson, 1981; Stahlman et al., 2021). We’re interested in the correlation between the response and the consequence, and we assume that the target behavior occurs when we describe the contingencies. With positive reinforcement contingencies, we’ll respond frequently to obtain the reinforcer. With negative reinforcement contingencies, we’ll respond frequently to avoid the aversive stimulus (e.g., Deleon et al., 2001; Zarcone et al., 1996). People can detect and identify the direction of these correlations between their behavior and the consequences of their actions (e.g., Chatlosh et al., 1985; Wasserman & Neunaber, 1986).

When selecting examples for the reinforcement contingencies, it seems to work well to choose everyday examples that students have experienced and then fade those examples to better controlled (and clearer) applied and then basic situations. For positive reinforcement, an everyday example is that asking for a raise (target behavior) is maintained by earning more money (positive reinforcer). For negative reinforcement, an everyday example is that leaving work early (target behavior) is maintained by escape from work (negative reinforcer). Asking for a raise and leaving work early do not serve the same function – one response produces more money, and the other response removes an aversive situation. For positive punishment, an everyday example is that arriving late to work (target behavior) is punished by social disapproval or being reprimanded by a supervisor (positive punisher). For negative punishment, an everyday example is that leaving work early (target behavior) is punished by having scheduled hours cut and thereby earning less money than expected (negative punisher). Everyday examples can help ease students into thinking about the functions of their behavior and potentially make learning about how nonhuman animal behavior also conforms to the reinforcement contingencies more palatable. For a finer discrimination between critical variables (e.g., Johnson, 2014; Layng, 2019; Markle, 1975), the examples could include the same target behavior and different consequences. For this activity, students will learn about the four reinforcement contingencies by diagramming examples. Each student should specify the antecedent, target behavior, consequence, overall contingency, and effect on future behavior.

Descriptions of contingencies:

- Bright sunshine: put on sunglasses → remove pain/blinding light

- Put on sunglasses → poke yourself in the eye

- Overcast weather: put on sunglasses → unable to differentiate between objects

- Put on sunglasses → look fashionable

We’ve got four different scenarios with the same target behavior, and by changing the context for that behavior, we entirely change the function of the behavior. This nicely illustrates how we need to consider the antecedents and consequences of behavior even if we have experience identifying the target behavior and assume its function based on past situations. Misidentifying the function of behavior in everyday life examples might not be harmful, but incorrectly identifying the function of a target behavior and establishing a treatment plan for that assumed function can be extremely detrimental for those receiving behavior analytic services. That is, assuming that inappropriate behavior is maintained by positive reinforcement and attempting to use a negative punishment procedure might not reduce the inappropriate behavior. If a learner is engaging in disruptive behavior in class that the teacher assumes is maintained by attention but is actually maintained by escape, then an intervention that incorporates time-out would increase instances of disruptive behavior rather than decrease those instances (e.g., Bolstad & Johnson, 1972; Broussard & Northup, 1997; Northup et al., 1995). The distinction between contingencies may seem arbitrary in the classroom, but by using everyday and practical, applied examples, students might gain an appreciation for the contingencies and learn to correctly identify their examples.

Image credits:

- Cover image provided courtesy of Helena Lopes under Pexels License

- Image provided courtesy of author

- Image provided courtesy of author

- Image provided courtesy of author