PREVIOUSLY IN THIS SERIES

QUEST #1 We need to be more behavioral about this

QUEST #2 A *WIDER REACH* is within our reach

QUEST #3 No-Paragraphs Naomi and the tyranny of text

In the previous post of this series, I went to some lengths to explain what ought to be an obvious point: The long blocks of scholarly text that We Who Have Gone To Graduate School prefer might be a poor way to disseminate behavior analysis to People Who Are Not Behavior Analysts (PWANBAs). Among the empirical facts of that argument: Scholarly text can be rather joyless, and people like some emotion in the things to which they devote their time and effort. [By the way, there’s a sizable literature on the effects of emotion on memory; here’s a rather nuanced review.]

Telling Isn’t Teaching

We Who Have Gone To Graduate School are so immersed in a world of text that’s designed for explanation that we forget how uninteresting, how unstimulating, this is to many people.

For example, people are willing to pay for college instruction — which is based on text resources that can be obtained for much less than the cost of tuition — because they know that, absent artificially created circumstances, they won’t do the necessary textual deep dive. [Doubt me? If you teach, try announcing that your upcoming reading assignment will be super interesting and professionally valuable, but not covered on the test. See what happens.]

Readers of the present post are unusual because of a behavioral history that makes “finding out” from explanatory text inherently rewarding. To build up the necessary conditioned motivating operations took a long time and a lot of special experiences. Unfortunately, other people may not come similarly equipped, so some targeted leverage might be necessary to hold their attention long enough for some useful learning to filter in. Alternatives to academic text can lean directly into this mission, with a primary tool being the telling of a good story.

But Story-Telling CAN Be Teaching

It has long been understood (though often not by academic types) that you can teach and influence via “Trojan horse-ing.” Entertain first, and then make sure the entertaining serves a larger purpose. As all great communicators know, the bread and butter tools of “informational” writing (data and theory and definitions) are, in isolation, attention repellents, whereas a good story is an attention magnet. Phil Hineline, in introducing a behavioral analysis of narrative, noted this effect of story telling on his own behavior:

A good novel or mystery story can make a shambles of my work routine. Too many times, when I’ve begun reading a novel or mystery story despite having important work to do I read late into the night, becoming ineffective for the following day.

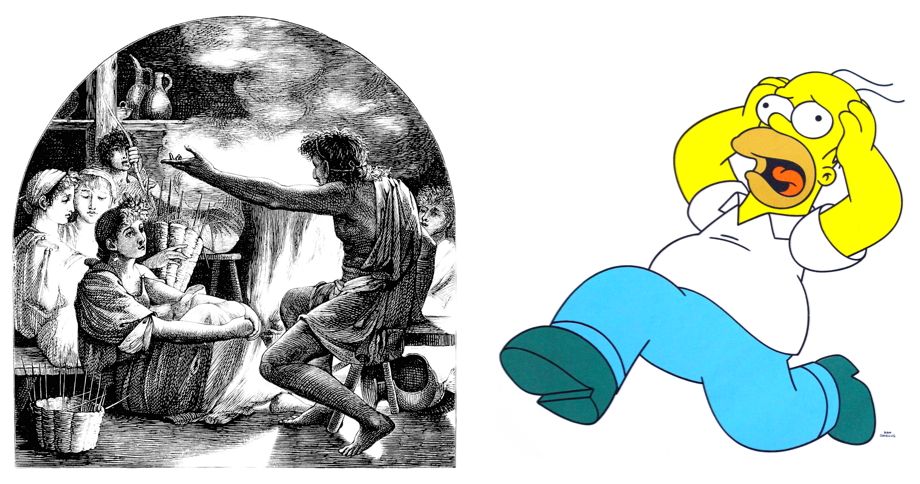

In the days before widespread literacy, well-crafted stories like those of Homer’s epics and Shakespeare’s plays could hold people’s attention for hours straight. And we know from historical tales that stories can teach — for instance, many people who have long forgotten their American History classes know about key persons and events of the American Revolution from the Broadway play Hamilton. [Yeah, some of the “facts” in Hamilton are wrong, but those are exceptions that prove the rule, for people remember Lin-Manuel Miranda’s narrative indulgences better than what history courses told them. It probably doesn’t hurt that Hamilton is a musical, with music being another powerful attention-holding mechanism — something I’ll explore a bit more in Part 5 of this series.]. And, of course, contemporary visual media like TV and film and associated binge-watching on streaming services demonstrate further how story-telling can hold attention.

Here’s a tiny example. Check out what Master Story-Teller Aubrey Daniels does, at about 0:39 of this short clip, while explaining the difference between praise and reinforcement. His brief story, which takes all of 20 seconds to tell, conveys a lot, and coupled with the rest of the video provides a memorable guide to how social reinforcers depend on social relationships.

Throughout his long career in performance management, Daniels has understood that people love a good story — even, it turns out, when it’s about behavior analysis! Daniels’ ability to pick just the right story to get across an important point is part of the charm that made a New York Times Bestseller out of his book, Bringing out the Best in People: How to Apply the Astonishing Power of Positive Reinforcement. Daniel’s writing always does justice to behavior principles, but its folksy tone and liberal use of colorful anecdotes makes it tolerable — no, fun — to work through. If you haven’t looked at Daniels’ stuff, you should, and I think you’ll quickly conclude that, for consumption by PWANBAs, Daniels’ writing has few peers, and therefore makes a great model for those who seek a bigger audience for their ideas.

Another obvious example is Catherine Maurice’s Let Me Hear Your Voice. As most readers of this blog know, it details one family’s heart-rending search for effective services for a child with autism. But there are other great stories. For instance, in classes I often assign What Shamu Taught Me About Life, Love, and Marriage, Amy Sutherland’s engaging account of how writing a book about animal trainers who employ behavior principles affected her personal life. And although I’m a rabid fan of the hopeful tale of child development told by the data in Hart and Risley’s Meaningful Differences, a much better (more story-driven) read on the same theme can be found in the first few chapters of Dana Suskind’s Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain.

Mands and Motivating Operations

As Ronnie Detrich (2018) has noted, many stories function as a mand in tact’s clothing. They often describe one person’s journey, but there is an implied rule for what you, the reader, ought to do to get similar results.

When a speaker tells a story as part of a dissemination strategy that speaker is manding for adoption, even if that mand has many topographical features of a tact. The story is probably more effective if it is not obviously a mand. Politicians have long used storytelling as a means of manding for votes. For example, in nearly every election cycle one will encounter a television advertisement in which a constituent tells an inspirational story about a candidate’s passion, values, and effectiveness. For instance, “When Senator Jones heard about the water problem at our elementary school she worked night and day to make sure our kids could be educated in safety….” Sometimes the story communicates that a candidate’s political opponent does not share the proper values and, if elected, will take actions that can harm the subject of the story and, by extension, the voters. For instance: “Mr. Smith wants to cut funding for our schools. If Mr. Smith is elected, we will not be able to make our aging schools a safe place for our children to be educated.”

So, of course, you too ought to vote for Mr. Smith. In other stories the implied rule is to be more (or less) like a key character. This is one reason why personal testimonials make for great advertising: They are nominally about some other person, but they suggest the desirable consequences that will follow if you mimic their product use. But to have this effect a story has to hold attention.

As Phil Hineline and Lyle Grant have both described, instead of depending on pre-existing motivating operations the way “informational” text does, stories expressly manipulate motivating operations. They’re built so that each part of the story makes you want to know the next part. Think about it this way: No story about behavior analysis makes people want behavior analysis unless they first want to know the story. The reason Let Me Hear Your Voice could have such an impact on public demand for applied behavior analysis is that, first and foremost, it is an enjoyable read. You care about that family and you want that daughter to get help. You excitedly flip to each new page to find out what happens next.

Our discipline hasn’t studied story-telling enough to identify best practices — the Hineline and Grant analyses are speculative — but in fields like English literature and journalism they have a pretty good idea about how to create a story that works. We ought to learn from those folks. In the meantime, note that a critical component of good stories seems to be the juxtaposition of content that’s pleasant and unpleasant to learn about. For instance, people like a transition from text that’s negatively emotional to test that’s positively emotional. Check out this video of novelist Kurt Vonnegut commenting on the effect.

It’s Not the Volume of Text, It’s What You Do With It

So, I’m advancing a “if you tell a good story, they will come” hypothesis.

In other words, whatever medium we may choose for disseminating behavior analysis, we could make more headway by telling good stories rather than simply “educating.” Let Me Hear Your Voice may be 400 pages of words — and, remember, huge chunks of text tend to scare people off — but nevertheless a lot of text-averse people have read and been influenced by that book. Pretty sure even No-Paragraphs Naomi would enjoy it.

Another productive use of story-telling can be found in Dardig and Heward’s Let’s Make a Contract, a manual for parents about behavior contracting (see a review of the book here). After briefly introducing the fundamentals of contracting in plain language, the book presents a series of short stories that illustrate the uses (and pitfalls) of contracting in everyday situations. These stories show the “how to” rather than tell it.

And by the way, at last count the book was available or in development in these languages: Arabic, Ajerbaijani, English, French, Hebrew, Italian, Korean, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovik, Spanish, and Turkish. This is a big deal, because it goes without saying that If you want to reach PWANBAs, you need to communicate in a language they understand.

Alternative Media for Dissemination

Conclusion: Once we’re open to reaching PWANBAs by telling informative stories rather than by “educating” in the classical sense, it becomes possible to consider where, besides journal articles and books, we might tell those stories. If I’ve done my job so far, then you should expect me to weigh in on the side of short-form media that employ limited wordage in accessible ways. There’s historical precedent for this. For instance, the two primary intellectual parents of behaviorism, John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner, were not above penning the occasional article for popular-press magazines like McCall’s and Ladies Home Journal. If Watson and Skinner could explore alternative ways of communicating with the general public, why shouldn’t we? That’s the focus of Part 5 of this series. Coming soon.

Postscript

To find out where Watson and Skinner published in the popular press, see Bruno Sappason’s Watson bibliography and the B.F. Skinner Foundation’s Skinner bibliography.