PREVIOUSLY IN THIS SERIES

QUEST #1 We need to be more behavioral about this

QUEST #2 A *WIDER REACH* is within our reach

For the better part of a semester, my undergraduate student Naomi looked to be a star. She aced brief quizzes based on the lectures and produced beautiful small weekly assignments. In group work she was a natural leader and she clearly understood a lot of the course material. When it came time for the big, end-of-term paper, however, Naomi’s was an abject disaster. What she submitted was barely even recognizable as the paper that I had assigned. Perplexed by this reversal of fortune, I pulled out my lengthy, step-by-step instructions for creating the paper and asked Naomi what in it had led her astray. “Oh, Dr. Critchfield,” she replied, somewhat amused and conveying no hint of irony or sarcasm, “I don’t read paragraphs.”

I was too flabbergasted to ask Naomi precisely what she meant by that. But the general message was clear: For Naomi, lots and lots of printed words on a page functioned as a big old S-. No matter how carefully crafted, those words did not invite Naomi in and could not, therefore, exert any instructional control.

In the moment, Naomi struck me as a strange outlier in our text-driven world, yet upon reflection I suspect We Who Have Gone To Graduate School grossly overestimate the society’s tolerance of the printed word. Naomi’s approach to (er, avoidance of) blocks of text may be partly generational, as she grew up in a world dominated by brief social media posts. In such a world people might not get a lot of practice consuming lengthy text passages. But the truth is that most people, of all generations, don’t find large blocks of text inviting and they don’t go out of their way to consume them. Consider that classic long-form collection of paragraphs called book. A fairly recent Gallup Poll showed book-reading among American adults reaching an all-time low. Reportedly, 57% of Americans tackle between 0 and 5 books in a year, with all age groups showing a decline in book-reading since 2012. The steepest decline was among college graduates — pretty informative when you consider that this is the only captive population of adults that is nominally required to read books.

Reading is Hard

Let me be super clear about what I’m not doing here — this is not some Baby Boomer’s civilization-is-going-to-hell-in-a-handbasket rant. The reality is that consuming big chunks of text has always been hard work for most people. Writing was invented only about 5500 years ago, which means that for well over 95% of our species’ existence we operated without it. The printed word began to be distributed widely only in the 9th through 15th Centuries, and literacy only became the norm in industrialized countries in the 19th and 20th Centuries. It’s still a minority outcome in many places.

My point: Reading as a cultural phenomenon has been superimposed upon human biology and traditions that evolved for other reasons. Reading is hard, therefore, because in the context of our species’ history it’s “unnatural” (and the challenge is considerably greater when text is infused with numerical information, as we often see in professional writing). With the right kind of instruction and practice, of course, just about any person can learn to read. But as a point in contrast, compare reading to music. Reading and writing are hard-won victories. Across the last couple of centuries, we’ve had to create schools and other special institutions to promote reading (and we’re not even very good at that — for instance, the average American reads at the 7th or 8th grade level). But every human culture ever examined has had music, and just about everyone in every culture participates in it in some fashion (they hum, sing, play instruments, dance, etc.). Apparently, compared to reading, music is easy.

I’m Just Advancing an Untested Hypothesis Here, But Maybe the Way to Entice People Who Aren’t Behavior Analysts Isn’t With Hundreds of Pages of Technically-Precise Academic-Style Text

And with this as backdrop, consider how often we try to disseminate behavior analysis to People Who Are Not Behavior Analysts (PWANBAs) with big chunks of traditional academic text. For much of our discipline’s history the preferred media for spreading the good word have been journal articles and professional books (like textbooks). I’ve been guilty of this attentional bias in recent posts, where I looked at how much non-scholarly attention journal articles received from places like the news industry and social media. And it’s great when this stuff gets noticed — for instance, check out the Behavior Analysis in Practice article that, through news reports, reached a potential audience of 81 million people. But let’s face it… most behavior analysis journal articles do not garner news coverage and most do not get much attention in social media (or from everyday people in any other context).

Yes, behavior analysts have also created trade books, which are aimed at the general public, and we’ve had some noteworthy successes. For instance, Foxx and Azrin’s Toilet Training in Less Than a Day has been purchased by more than two million PWANBAs! But one major problem with trade books is that they are still books — lengthy repositories of text — and we’ve already seen that most people don’t read a lot of books. Unsurprisingly, most attempts by behavior analysts to create trade books have been quickly forgotten.

Also, when it comes to marketing the discipline, it doesn’t help that many of our “popular press” books read a lot like scholarly works. Here’s a challenge for you: Keeping in mind that the average American PWANBA reads at the 7th or 8th grade level, pull 500 words or so from several popular-press books of your choice related to behavior analysis, and run those samples through one of the many free reading-difficulty calculators available online. You will find that in most cases the reading difficulty far exceeds the comfort zone of the typical citizen. I’ve done this with Science and Human Behavior (which Amazon.com calls “Skinner’s most accessible book”) and Beyond Freedom and Dignity. Both register at the 12th grade reading level or above.

We also encumber our outreach efforts by talking to PWANBAs as if they were behavior analysts. In part this means including lots of technical jargon, which PWANBAs either misunderstand or perceive as conveying an emotionally unpleasant tone. For evidence, check out this article, which shows that the valence (emotional effect on a typical listener) of many behavior analysis terms places them among the most unpleasant English words (limited evidence suggests that the same applies to many behavior analysis terms in other languages).

A Case Study in Clunky Communication

Even separate from a reliance on jargon, there may be something about the way we communicate that lands with a thud where everyday audiences are concerned. I suspect that our strong commitment to operationism and determinism leads to word choices that PWANBAs find sterile and stiff — or perhaps joyless is the word I’m grasping for. Here’s a case study to illustrate. In 1956, Skinner and Humanistic Psychologist Carl Rogers co-authored a debate in Science magazine, which has a big subscriber base and doesn’t target any one specialized audience. Consequently, both Skinner and Rogers did a pretty good job of avoiding excessive jargon. Here then, are two men of similar age and education, writing at the same moment in the history of Psychology on the same topic for the same audience, relatively unencumbered by the peculiar vocabulary of a given theoretical system.

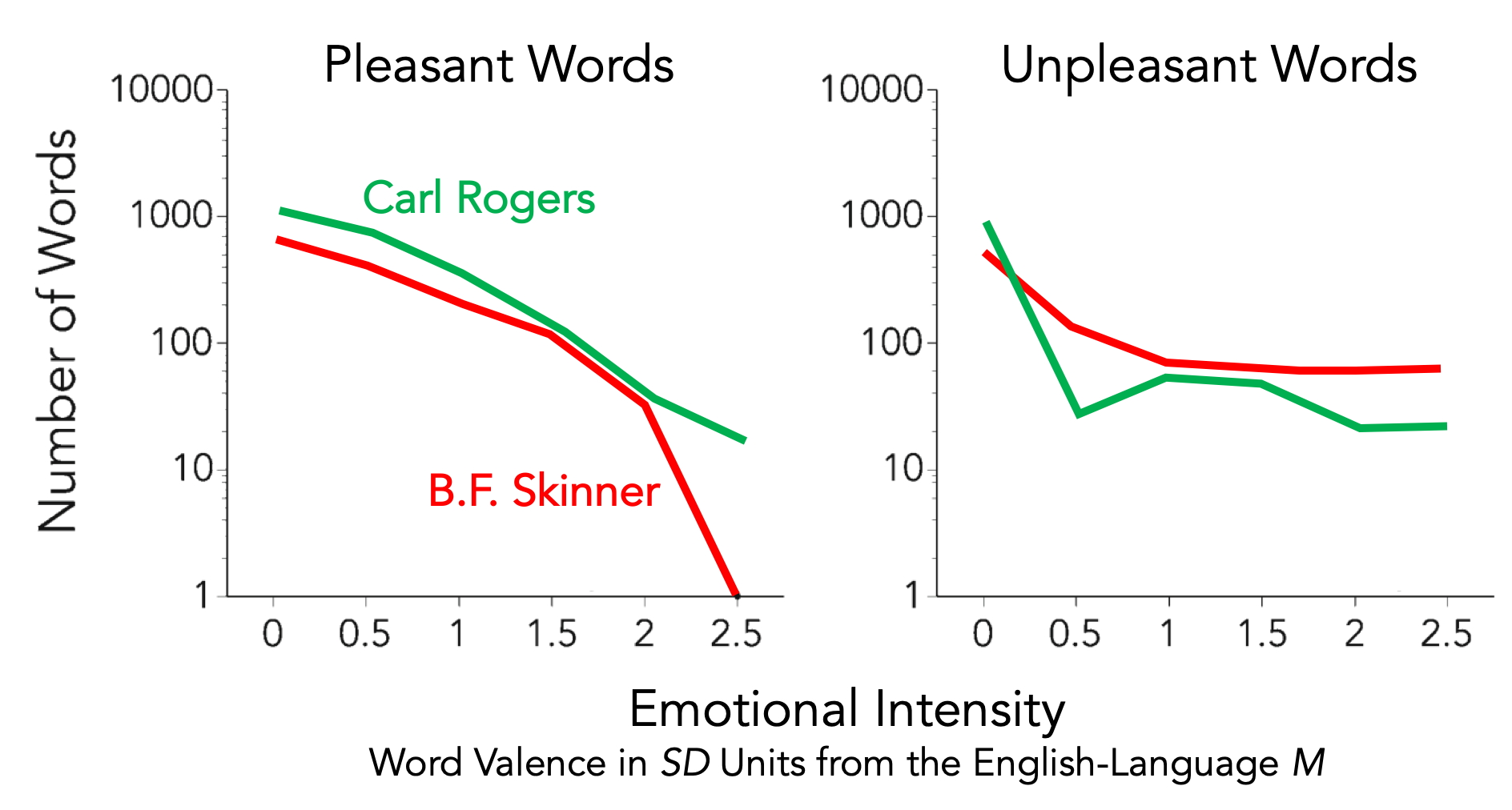

To understand the graph below (which is redrawn from this article), you need to understand three things about how word valence is distributed. First, all languages that have been studied so far have a ton of relatively neutral words, but overall more pleasant words than unpleasant ones. Second, strongly emotional words are relatively rare, but at the most extreme levels of valence, unpleasant words are relatively more common. Third, these two patterns apply not just to whole languages but also the communication habits of individuals, although there can be some individual differences, as the graph below shows.

The graph shows the prevalence, for text authored by Skinner and Rogers in the Science article, of pleasant and unpleasant words of varying degrees of emotional intensity. You can see that across the intensity scale, Rogers used more pleasant words than Skinner (note that, because of the logarithmic ordinate, small looking differences can actually be pretty big). Across most of the intensity scale, Skinner used more unpleasant words than Rogers. Of the two, then, Skinner is the Debbie Downer (or, in the immortal words of Spiro Agnew, the Nattering Nabob of Negativism), at least as depicted by his word choices. Oh, and in case you’re wondering, Skinner’s communication style is pretty similar to that of several other behavior analysts who have been praised (by other behavior analysts) for their capacity for clear communication.

Let me summarize thus far: People don’t tend to like lots of text, and at least in traditional writing formats we behavior analysts don’t tend to produce the kind of writing that might overcome their aversion to text. So here’s my central question: If we want PWANBAs to know about and appreciate behavior analysis, shouldn’t we “start where the organism is” by designing our outreach efforts around their high-probability verbal repertoires? And shouldn’t we simultaneously prefer modes of communication that might avoid the worst of our excesses when it comes to jargon and dour tone?

Common sense suggests two general strategies for solving this problem: Using text in different ways, and using media other than text. Those possibilities will be explored in Parts 4 and 5 of this series,