PREVIOUS POSTS IN THIS SERIES

#1 HOW MUCH DO WE VALUE DEMOCRACY?

#2 A “LOVELY” DEPICTION OF A TERRIFYING TREND

#3 THE AJR INITIATIVE: A WAY TO PRACTICE WHAT WE PREACH

Politics as Tribal Warfare

It’s been a troubling year in politics — actually the continuation of a troubling era that’s been afflicting us for a while. The problems are so widely known that I will not bother to cite specifics. Everyone, it seems, is aware of the erosion of political norms in democratic nations. Political parties appear to absolutely hate one another. Ditto for voters. My grandmother used to say that it’s impolite to bring up religion or politics at the dinner table… but these days, it’s not even safe. Someone could get punched.

I’m not exaggerating. I read a news report a while back about three members of an extended family who ended up in the emergency room when a Thanksgiving dinner brawl erupted. A daughter’s college boyfriend had the gall to malign her dad’s favorite presidential candidate. Fisticuff ensued.

As a Columbia University conflict resolution scholar notes:

When you have the kinds of conflicts that are hot today—the Trump supporter and hater conflict, the opposing values, the tribalism and contempt—those conflicts are not negotiable. They’re not… responsive to talking things out.

The political game has gotten so contentious (see the Postscript) that political parties seem uninterested in governing and, instead, are intent on maligning their rivals and thwarting their attempts [if any] to govern. Political leaders, once valued for competence, are now selected for their abilities as a street brawler, turning the political process into the ill-begotten child of Kabuki Theater and professional wrestling (that’s not just my interpretation; if you can get past the paywall, read this brief analysis by The Economist).

As political institutions appear to rot from the inside, the reaction of most intelligent people I know — regardless of political affiliation — is one of bewilderment. Have people gone crazy? How in the world did we arrive at this place where politics-as-a-quest-to-govern has been replaced by overt tribal warfare?

The present series of posts is predicated on an answer that should be familiar to our readers: The organism is always right. If you buy into this thing called behavior analysis, you lead with faith in the notion that what people do, no matter how peculiar or self-destructive it might seem, is governed (pun intended) by the natural laws of behavior. Faith is the easy part, however, because the political world is a roiling cauldron of competing, complementary, and interactive influences. Simple cause-and-effect is rarely on the table, and we sure as heck are not going to make sense of most political behavior using the linear single-case experimental designs that are out disciplines bread and butter.

But we can start by taking in the maelstrom before us, educating ourselves about its nuances, and looking for the behavioral lines of fracture. Here I’ll examine the U.S. situation with which I’m most familiar (other political systems deserve their own analysis, but he organism is right there, too).

Fragile Cooperation

Now, when political competition overshadows all hope of co-existence and cooperation, it’s worth remembering that in general cooperation may not be the human comfort zone. Sure, humans cooperate more than a lot of other species (a thousand humans might participate in a blood drive or or show up for a political rally, but “I should like to see anyone, prophet, king, or God, convince a thousand cats to do the same thing at the same time” — Neil Gaiman). But research shows that, for humans, robust cooperative behavior tends to sustain mainly in two special circumstances:

(1) Targeted cultural practices shape and reinforce cooperation from a young age, giving it some behavioral momentum into adulthood.

This circumstance definitely does NOT exist in the U.S. and a number of European nations, places where contentiousness rules. Parents treat 6-year-old soccer matches as blood sport. People harass servers, flight attendants, and others in service roles every time they don’t get exactly what they want. Social media disagreements instantly turn venomous. As one psychologist has written, there’s a technical name for people who emit such behavior:

At 5:00 AM on a Monday morning, I received what felt like an accusatory text-message from a colleague. My immediate reaction was to fantasize about ways to shred my relationship with this person—a relationship I’d been painstakingly building for almost ten years—by firing back the nastiest response I could pack into a text message…. What had happened? I immediately came out swinging; or, put another way, I instantly turned into a dick (emphasis added).

For the linguistically squeamish, here’s the official operational definition of that term: “a mean-spirited, self-serving individual who thinks and acts as though everyone else in the world can only be understood―and whose only importance is defined―in terms of their relationship to himself or herself.”

In some places, people are expressly taught how not to be a dick. In Norway, for instance, people begin participating in cooperative rituals from a very young age — “a cultural practice that creates an environment that nurtures prosocial and cooperative activities” (we’re not so lucky in the U.S., where the best you can do, once you reach flawed adulthood, is buy a book on how to counter the already-engrained impulse to be a dick).

(2) Current contingencies directly encourage cooperation.

In everyday life the main “special circumstance” would be social pressure. For instance, in Norway, because cooperation is reinforced from a young age, by the time you’re a grown-up, if you act selfishly you know immediately that your neighbors don’t approve. In Norway, being a dick costs you.

Gridlock

In American politics, there used to be contingencies that discouraged being a dick, or that at least rewarded occasional cooperation. Here’s a quick civics lessons for those fortunate enough not to face U.S. politics every day. There are only two functional political parties in the U.S., and the federal legislative body, the Congress, can pass needed laws most easily with at least some support from both parties. One side effect of the contentious zeitgeist is that in recent years fewer and fewer laws have gotten created.

The most visible manifestation of this problem is Congress’ recurring inability to even create an annual federal budget, resulting in that uniquely American phenomenon, the government shut-down. But lots and lots of public needs don’t get addressed when Congress can’t seem to do its job.

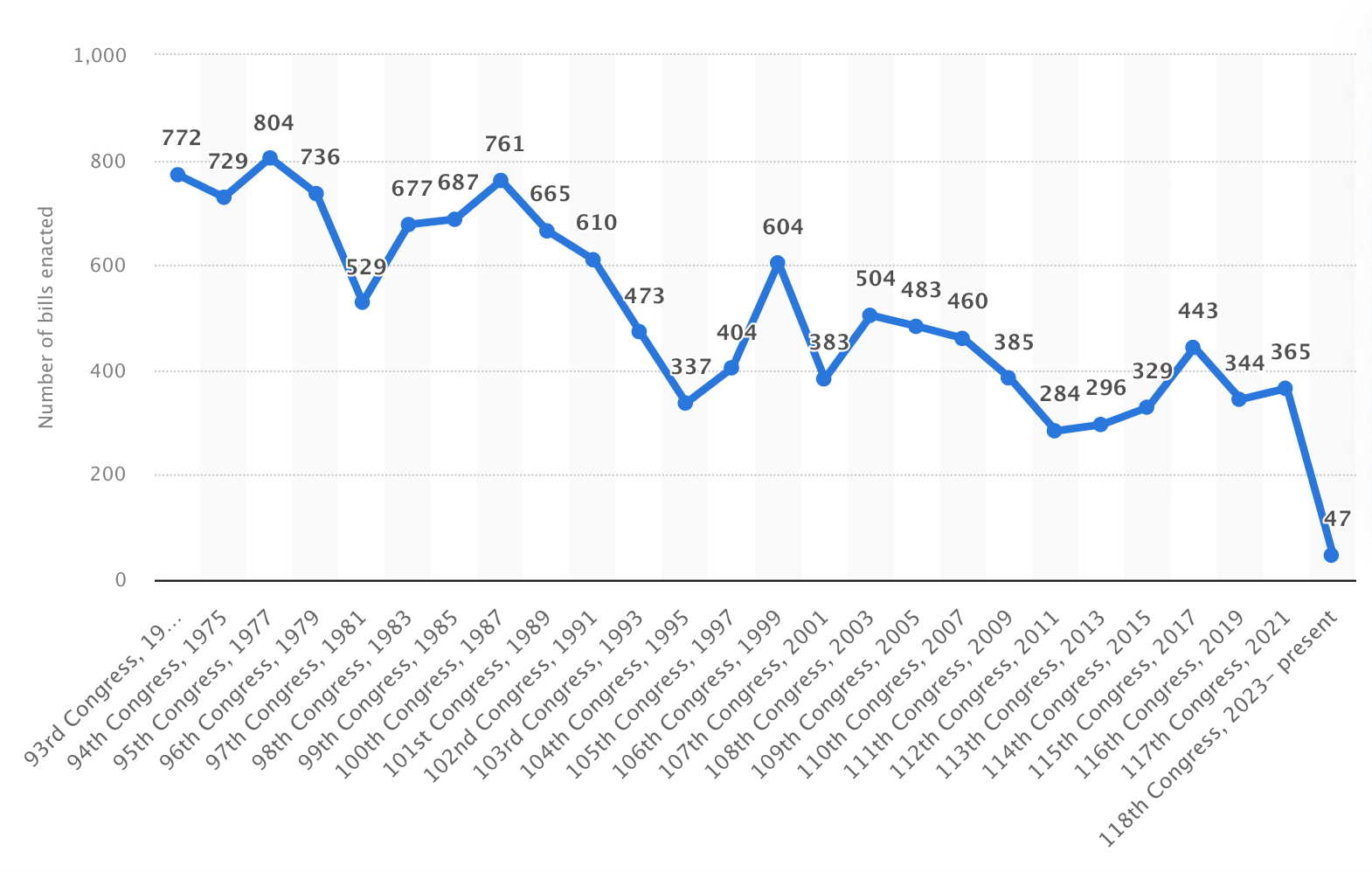

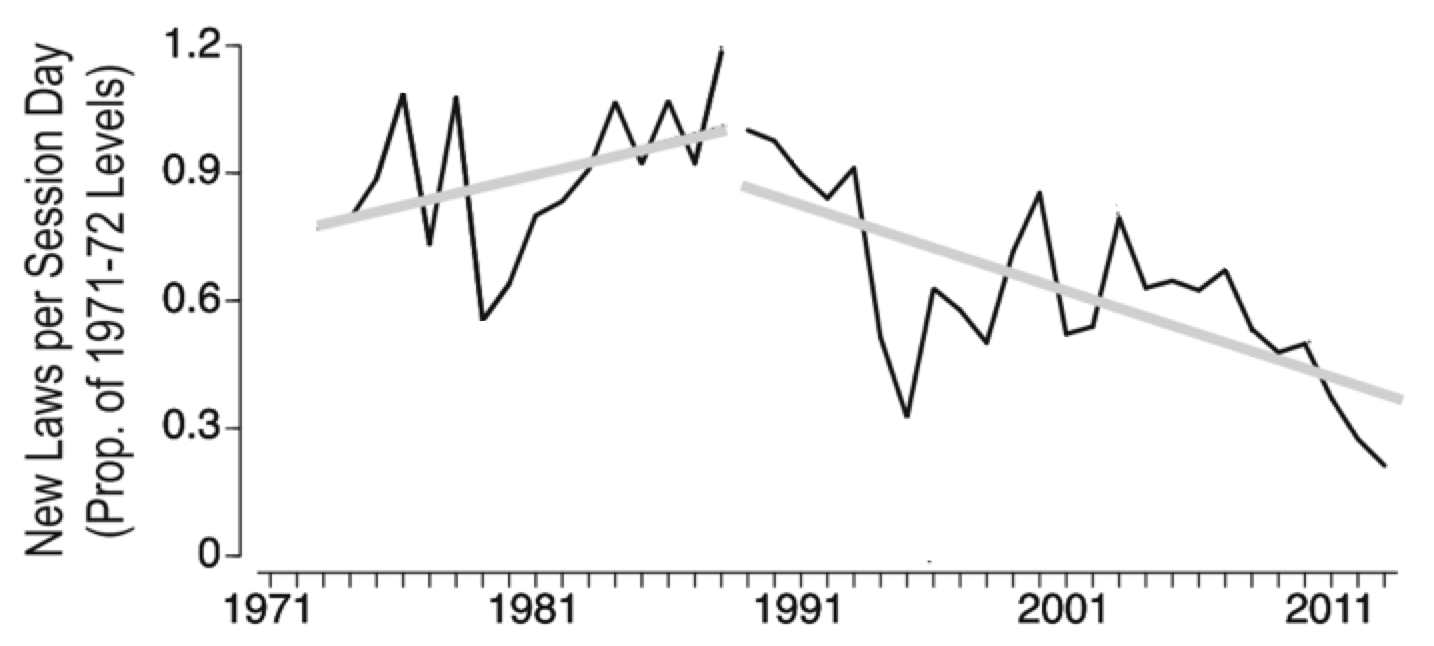

WHY can’t Congress do its job? To understand this, you have to start with the reality that only special circumstances create cooperation. A few years back, my colleagues and I examined some changes in “special circumstances” that might be responsible for the legislative gridlock. Below is a measure of Congressional productivity from the early 1970s to the early 2010s. Using least-squares regression we determined the best-fitting trend lines, which suggested two distinct phases.

Phase 1 looks like a possible gradual increase in annual legislation, though the trend isn’t statistically significant. Phase 2 is a significant decrease in legislation.

Contingencies of Gridlock

Since the political organism is always right, what changs that could explain the shift? There. are several likely influence.

Mid-1980s through 1990s

- Political parties perfect a “soft money” loophole in campaign finance laws which allows corporations and special interest groups to donate unlimited amounts to political campaigns. Because candidates need cash to fund campaigns, this funding tends to give disproportionate influence to a relative few donors, often with extreme political views.

- Special software is perfected for gerrymandering, the creation of noncompetitive political districts. In such districts, getting elected means earning the approval of only one party, who may punish a candidate for collaborating with the other party (see “Americans prize party loyalty over democratic principles“).

First Decade of 2000s

- The rise of frequent political polling and social media exacerbate pressure on legislators to please a politically homogeneous voter majority in home districts.

- A Supreme Court ruling gives a relative few wealthy donors additional influence over political campaigns.

- Congress eliminates its “earmark” custom, in which Legislator A could pad a bill with unrelated provisions favoring other legislators’ interests, thereby providing motivation to vote across party lines.

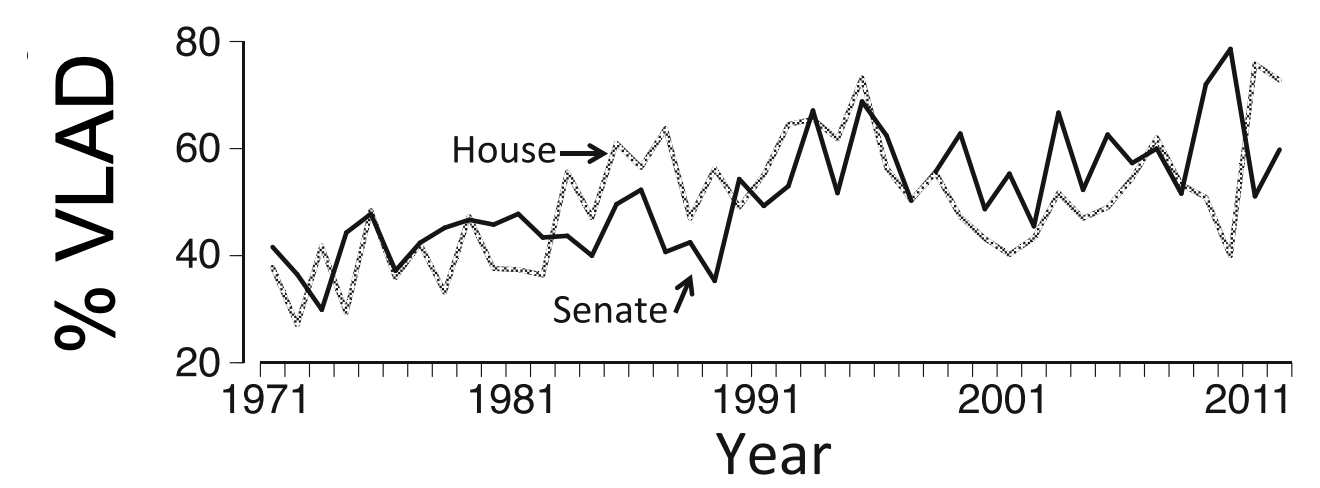

Correlation doesn’t verify causation of course, but note how all of these changes cluster temporally around the phase-shift in Congressional productivity. They all push in the same direction by rewarding legislators’ strict allegiance to their own party and/or discouraging cooperation with the other party. The result has been a dramatic trend toward “party line” voting on proposed bills in both Congressional chambers (House and Senate). Party-line voting is when members of each party vote exclusively with each other, and exclusively in opposition to the other party (inset; VLAD = voting like a dick).

You can see that, to a some degree, cooperation was once the norm, such that party-line voting happened for only a minority of bills. Nowadays, competition rules, with party-line voting in a majority of instances. Importantly, in a nation where slim political majorities are common, simple math dictates that it’ll be hard to get things done without some inter-party cooperation.

Oh, and by the way, some of this helps to explain why voters are more polarized too. When you live in a politically homogeneous district, and your social media feed gives you a single set of opinions, it’s easy to become ideologically rigid. Ditto when the only politicians you encounter constantly villainize the opposition. It’s a vicious cycle.

But, hey, the political organism is always right! Politicians and voters are merely doing what the contingencies of a broken system promote.

To say this, of course, fixes nothing, but it’s a start at getting past the “they’ve all gone crazy” bewilderment and moving toward getting a handle on some of the factors that probably are responsible for our fraught political landscape. There’s much more to discuss. A couple of guest posts on voter behavior are in development. Perhaps they will cast additional light on the nature of the problem. Stay tuned.

Postscript

Here’s a video from America’s Finest News Source, The Onion, which pretty well captures the contentious spirit if not the literal essence (maybe) of contemporary politics.