This week marks the official start of the Presidential election campaign season in the United States, though anyone’s who’s been paying attention knows that the unofficial campaign has been in full swing for quite sometime.

And if you’ve paid attention, you know that this election takes place in the shadow of much panic over the recent erosion of democratic norms in the U.S. and elsewhere. Some observers even say that democracy is close to total collapse. Factually speaking, there might be good reason for concern.

The worry is shared breathlessly in the media, not just because it might be correct, but also because of an assumption that people care. Threats to democracy are only newsworthy if people actually value democracy.

But do they really?

Just because democracy exists doesn’t mean people value it. Lots of things have their moment in the public consciousness but disappear without anyone missing them — think of the Yugo, the Bee Gees, Fruit Stripe gum, and the tradition of throwing apple peels on Halloween to predict your romantic future.

And voters make us doubt their commitment to democracy when they support politicians who openly detest democratic institutions (for instance, Bolsonaro in Brazil, Le Pen in France, and Trump in the U.S.). If voters install people like this into office, how much can they really love democracy?

Because you’re an empiricist, at this point you should be hungering to move beyond speculation. You should be asking, “How, using behaviorally sound methods, might one measure just how much people value democracy?” An interesting new article by Adserà and colleagues (“Estimating the value of democracy relative to other institutional and economic outcomes among citizens in Brazil, France, and the United States“) sought to do just that and soon I’ll share one of their key findings.

To help that study make sense, however, requires a bit of a dive into behavioral economics (for a nontechnical tutorial see here, and for a more sophisticated discussion of premises see here), the methods of which were approximated by Adserà et al.

Demand and Behavioral Price

A core idea in behavioral economics is that reinforcers don’t exist in an either-or fashion. You typically can’t say that, for a given individual, M&Ms are a reinforcer but Skittles are not. Rather, many tangible goods and activities (“commodities,” in behavioral economic lingo) can be reinforcers, depending on their price (meaning the amount of behavioral investment on which they are contingent) and other factors. When the price is low, many commodities are reinforcers. When the price is too high, a given commodity ceases to function as a reinforcer.

You probably already understand this principle at an intuitive level — for instance, there may be crappy movies on Netflix that you’ll happily watch when all that’s required is to press the remote from your sofa; you would never drive to the theater and pay a hefty additional fee to watch them. This is cost/value relationship the same principle underpinning the familiar progressive ratio reinforcement schedule, in which the response requirement rises systematically until a “break point” is achieved in which behavior ceases. In progressive ratio schedules, the break point is the behavioral price at which a commodity stops being a reinforcer. You might say it’s the price at which a commodity is no longer “worth it.” And this makes for a good standardized measure of reinforcing value.

In behavioral economic methods, demand, defined as how much of some commodity is “purchased” (earned), is studied as a function of price. Here’s a simple example from a study by Roland Griffiths and colleagues that sought to understand the reinforcing value of caffeine (doesn’t sound like the most compelling research question, I know, but see Postscript 1).

Adult men lived in a residential laboratory where they could work for up to 10 “doses” a day by riding an exercise bicycle for a specified amount of time. On different days a “dose” was either a cup of coffee (caffeinated or not, unlabeled) or a capsule (containing caffeine or a placebo, unlabeled). The price of a dose varied across days from 0 minutes of riding (the men just had to ask for a dose) up to 32 minutes of riding.

The figure below (left side) shows that demand dropped as price increased. Note that the (presumably) least attractive commodity, placebo capsules, functioned as a reinforcer when the price was low, but demand dropped off quickly as price rose. Caffeinated capsules (not shown) and caffeinated coffee were more resistant to this effect (decaffeinated coffee fell in between these and decaf capsules). The take-home notion to derive for present purposes: The more resistant a commodity is to price increases, the stronger a reinforcer it is.

Hypothetical Purchase Tasks

As an important aside, I hope you can see how difficult it was to run the Griffiths caffeine study. The participants had to be housed and fed for more than 6 weeks and were compensated financially for their time. The lab had to be staffed 24 hours a day. Needless to say, most labs simply could not mount a study like this (arrangements like this usually are reserved for studies with captive animals). If this were the modus operandi, not much human behavioral economic research could be done.

Another hurdle to behavioral economic research is that it’s impractical to deliver some commodities of interest. For instance, imagine an experimental condition to measure how many alcoholic beverages a person would consume if drinks were free. If the answer were 10 or 20 (not implausible, as people who’ve been to college parties understand), medical risks would be arise that no research team can ethically assume.

To get around problems like these, behavioral economic researchers have created hypothetical purchase tasks, in which price-consumption relationships are examined in what-if scenarios. As a way of standardizing across investigations, price is usually operationalized in terms of money. So, instead of riding a bike for a dose of drug, a participant might be asked how many doses they would purchase (and consume) at various prices. In hypothetical purchase tasks, then, verbal reports are taken as measures of consumption, and verbal reports of money expenditures stand in for direct measures of behavioral effort. This allows a variety of commodities and prices to be examined quickly and safely.

[Side note: If you’re a behavior analyst who’s been taught to be appalled at verbal report measurement and hypothetical scenarios, take heart. These procedures have been extensively vetted and their results correspond closely to “real” demand for various commodities (though see Postscript 2 for an important note on a limitation of these procedures).]

Value Depends on the Alternatives

The above graph (right side) shows the result of a hypothetical purchase task experiment that illustrates a second principle of behavioral economics: Reinforcing value of Thing X depends on reinforcing value of alternatives. Skidmore and colleagues (2011) asked college students how many alcoholic beverages they would purchase at an evening gathering given various price points ranging from $0 (free) to $20 per drink. In one condition, participants were told to imagine that they had an exam scheduled the next day. In another condition, no mention was made of next-day contingencies. In both cases demand dropped as price rose, but demand was systematically depressed in the “test” condition. One way to think about this result: Alcohol is a reinforcer, but its value decreases if consuming it means forfeiting other reinforcers (in other words, if you drink rather than study and show up to a test hungover, your grade is going to suffer).

Democracy in a “Hypothetical Vending Task”

Now you know enough to examine the Adserà study, which treated the free elections of democracy as an economic commodity and sought to quantify their value. There is, however, a key difference between democracy, so defined, and many commodities for which hypothetical purchase tasks are used to determine value: People in the three countries of interest (Brazil, France, and the U.S.), to a large extent, already have free elections, and thus have no need to “purchase” them. So instead of asking what they would purchase at a certain price, in the Adserà study residents of the three countries were asked if they would prefer free elections or a given amount of money (defined as a percentage income increase for everyone in the country).

That is, at what price would people be willing to give up free elections?

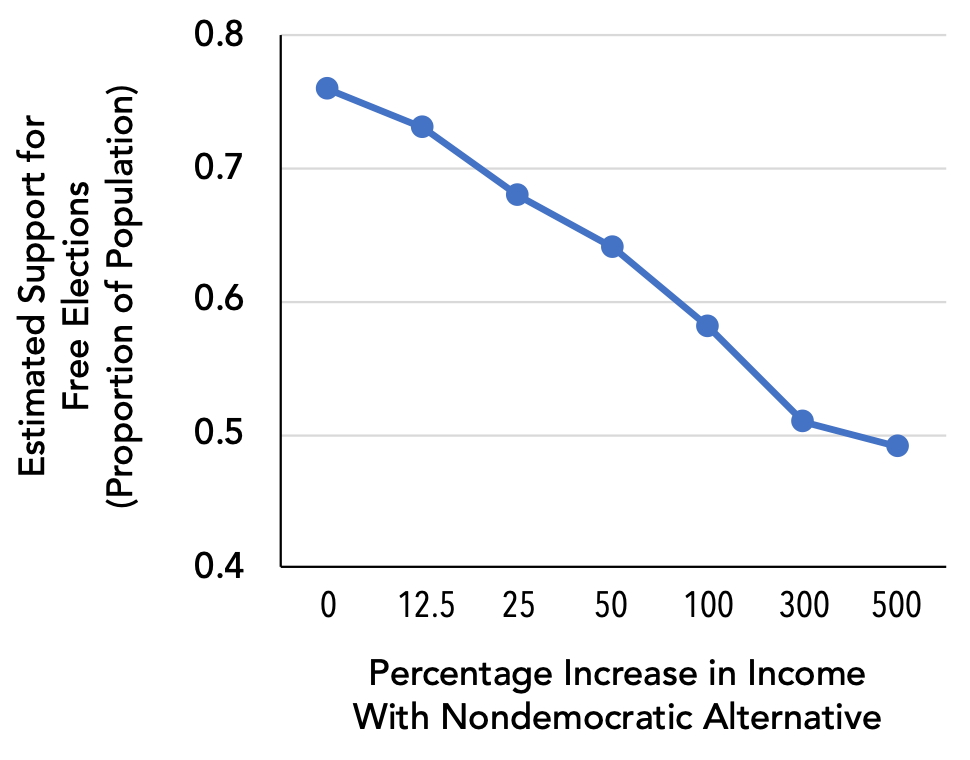

The graph at right shows the proportion of respondents (all three nations combined) who said they would prefer democracy over a given-sized increase in income (this is based partly on some statistical treatments that we need not delve into here). When retaining free elections is cheap, most residents prefer to have them. But when forced to choose between retaining free elections and receiving a financial windfall (but losing free elections), supporters of free elections become increasingly scarce as the windfall grows larger. Make the windfall big enough, and support for democracy becomes a minority proposition.

Gorking Out on Tyranny

There’s a tendency in everyday discourse to discuss political beliefs as if they’re characterological — sort of fixed traits, or at least firmly-held philosophical positions that are resistant to change. Hence in the U.S. we call people conservatives and liberals, as if you are one or the other, more or less in perpetuity. There is also a tendency to think of “democratic nations” in terms of residents’ political attitudes. We think of Americans, for instance, as people who straight out cherish democracy, and we like to think that that residents of nondemocratic elections would, if given the chance, embrace it at all costs.

The Adserà study makes clear that these are oversimplified ideas. What’s both illuminating and terrifying about the results is that they depict support for democracy as transactional. “Democratic” voters do generally like democracy, but they have a price, and they admit that they would abandon democracy for the right “compensation.”

This makes the occasional free election of tyrannical politicians, which at first sounds like an oxymoron, entirely expected, assuming they can offer up the right “compensation.” To start with, like all politicians, Bolsonaros, Le Pens, and Trumps of the world make economic promises, as explained in a recent review of Alberto Toscano’s Late Fascism (which sounds like it offers interesting commentary on what people value more than democracy):

Trump’s movement is conspicuously driven by nostalgia for America’s postwar affluence, for “the ‘Fordist’ heyday of Big Capital and Big Labor (generally coded as male and white) … for a racialized and gendered image of the socially recognized patriotic industrial worker.” Yet that era of rising if unequal prosperity was fueled by progressive taxation, widespread union membership and an unprecedented explosion of government spending and social welfare programs, all of which are not just anathema to the MAGA creed but unimaginable under current political conditions. The Trumpian false utopia promises the benefits of social democracy, in other words, without compelling the ruling class to pay for them.

But the “compensation” that anti-democratic politicians offer is not only financial. In the U.S., for instance, Trump promised to all but end immigration and to eliminate the boundaries of church and state (for Evangelical Christians, at least). To some voters, those outcomes might be more attractive than money — and, of course, than future free elections.

Another gambit commonly employed by tyrannical politicians is to nurture a cult of personality. According to the tyrant’s own story, in a world of weak and sleazy politicians who kowtow to insidious forces and propagate political inertia, only they have the fortitude to stand up and take independent action. Never mind if “taking action” means disregarding democratic institutions! In the U.S., Trump apparently benefitted substantially from voters’ frustration with the established political parties, with Congress, and with entrenched special interests. In cases like this, the “compensation” for voter support may simply be seeing an elected official who talks differently than the toadies who came before. Perhaps Trump voters were thinking, “Watching regular politicians try to negotiate our messy democratic system has been a shit show. Let’s get a man of action instead.”

If you want a colorful sense of how this dynamic works, I recommend a satirical article in McSweeneys entitled, “Inflation is high, so I’m voting for Gork the merciless.” From the article:

Gork has promised to slaughter our families, sell our children, burn our houses, steal our land, and enslave our people for generations, but milk prices went up, and even though they’re starting to come down, we might as well see whether Gork’s warlord approach is better for the economy.

Political support for a Gork makes zero sense if you think of beliefs like “support for democracy” as a fixed philosophy. But when free elections and other democratic institutions are viewed through the lens of behavioral economics, they are commodities whose value depends on the context.

The strong implication: You can’t simply depend on citizens’ “democratic ideals” to maintain free elections. Everybody, maybe, has a price at which they’d be willing to sell out democracy. With tyrannical politicians continuing to attract support in many putatively democratic nations, the challenge for supporters of democracy is make sure that such a price is never met. How to accomplish this remains uncertain, but a good start is to think of the institutions of democracy as commodities in a behavioral economic framework, in which value varies as a function of known factors. If there’s an election coming up near you, and you care about democracy, better study up on your behavioral economics.

Postscript 1: Note on Caffeine Reinforcement

Caffeine (see the Griffiths et al. study, above) is a weird drug. Humans ingest a LOT of it, with 75% of Americans reporting daily consumption, a privilege for which they spend around $1100 per year. This suggests a powerful reinforcer and yet, in contrast to most drugs that function as human reinforcers, caffeine is a sketchy reinforcer in nonhumans; see here and here). Moreover, for humans caffeine typically is embedded in flavored beverages and other products that could be reinforcing to consume even without caffeine. Finally, most drugs that humans use recreationally can serve as positive reinforcers, but at the time the Griffiths et al. study was conducted there was some debate about whether this was true for caffeine (the alternative is that it becomes reinforcing only after dependence creates withdrawal symptoms, in which case caffeine would be strictly a negative reinforcers). The Griffiths et al. study is rather elaborate because it was part of a concerted effort to see whether caffeine could be understood within the behavioral framework that explains most drug reinforcers.

Postscript 2: What Hypothetical Tasks Can and Can’t Tell Us

Here’s an important procedural note about hypothetical tasks: They work to the extent that participants have relevant behavioral experience. For example, ask me if I would buy milk at $6 per gallon, or whether I would go for a run if the temperature dropped to -10 F, and I can tell you, because I have been buying milk and exercising outdoors my whole adult life. But ask me if I would fight back against a mugger or give up one of the Titanic’s few lifeboats to helpless women and children, and I might give you an answer, but in truth I have no idea how I would respond because I’ve never been mugged or found myself on a sinking ship.

Our verbal projections of future behavior, therefore, are grounded in self-observations of past behavior. In the “democracy” study, people’s projections of what they would accept in order to give up free elections are somewhat plausible because (a) they have lots experience with money and (b) they live in nations with free elections. Change either of those conditions and the estimates become less plausible.

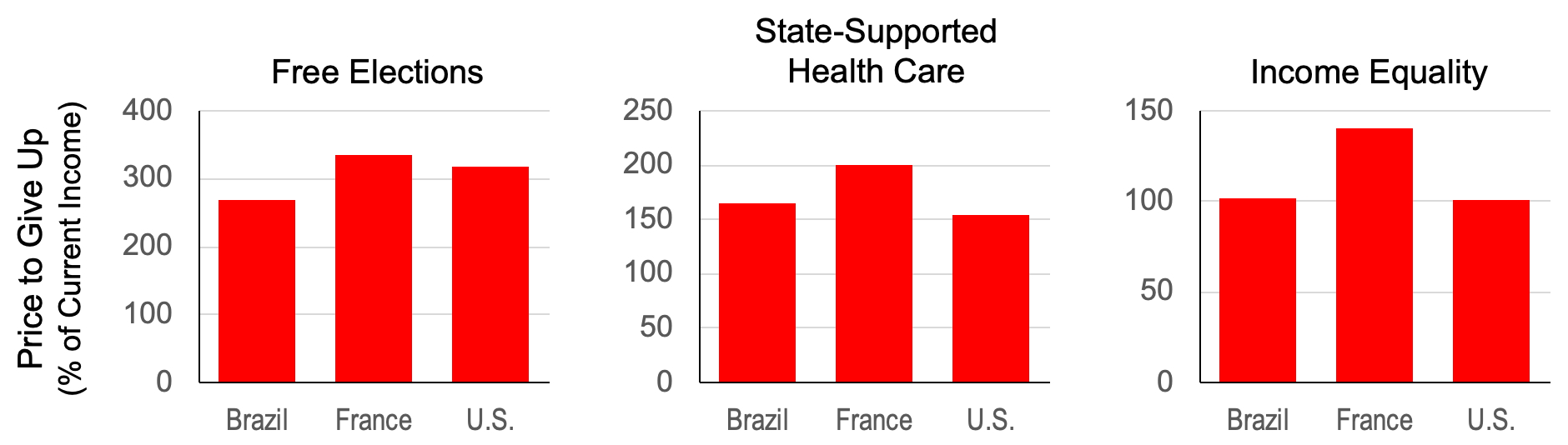

By the way, the Adserà study provides possible examples in which verbal projections may not be fully reliable. In the graph below, the left panel shows the average level of income at which at least half of respondents from three countries said they’d be willing to part with free elections (their price: roughly tripling their income). In addition to free elections, the researchers asked about the amount of extra income people would require to forego certain other benefits of a free society, including subsidized health care and income equality.

The middle panel seems to show that French residents value public health care more than their Brazilian and U.S. counterparts, and indeed the France-Brazil comparison has some credibility, because both nations offer free, publicly-funded health care. But the U.S. does not offer free health care to most residents, so it’s unclear whether U.S. respondents really understand what they’re being asked to give up.

Similarly, the right panel suggests that residents of all three countries place relatively little value (compared to the other societal benefits_ on income equality — they’d give that up for a low price (note the difference in ordinate scales). But none of these countries has ever had real income equality. The gini coefficient is a measure of income inequality based on the distribution of incomes in a society. It ranges from 0 (no income disparity) to 1 (extreme disparity). Current gini estimates are

- France = 0.32 (35th best among 163 nations), a score that’s considered “adequate” but not ideal

- U.S. = 0.41 (110th), a score that’s considered to represent “big income inequality“

- Brazil = 0.53 (154th), a score that’s considered to represent “severe income inequality“

We also don’t know how the individual respondents of the Adserà study fell within a nation’s income distribution. It’s simply not clear how all of this might affect the way residents value income equality, highlighting that in examining the results from hypothetical procedures you have to cast a critical eye on what is being measured and how it corresponds to participant life experiences.