I would not be just a nuffin’,

My head all full of stuffin’,

As witless as an elf…

Just because I’m presumin’

That I could be kind of human

If I only had a self.

Based on “If I only had a brain/a heart/the nerve,” by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg. © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

One of my recent posts caused a bit of a stir when some readers found its portrayal of a Famous Behavior Analyst to be insufficiently respectful. Yeah, okay, technically they were right, as the post included a tongue-in-cheek illustration of said Famous Behavior Analyst that, while not meant to be hostile, also fell well short of encomiastic. One writer on social media suggested that I must really despise this Famous Behavior Analyst because I would never-ever-ever have depicted, say, the great Don Baer in such a whimsical way.

There’s something fascinating and important in this that I’d like to discuss — but first, let’s clear one thing up.

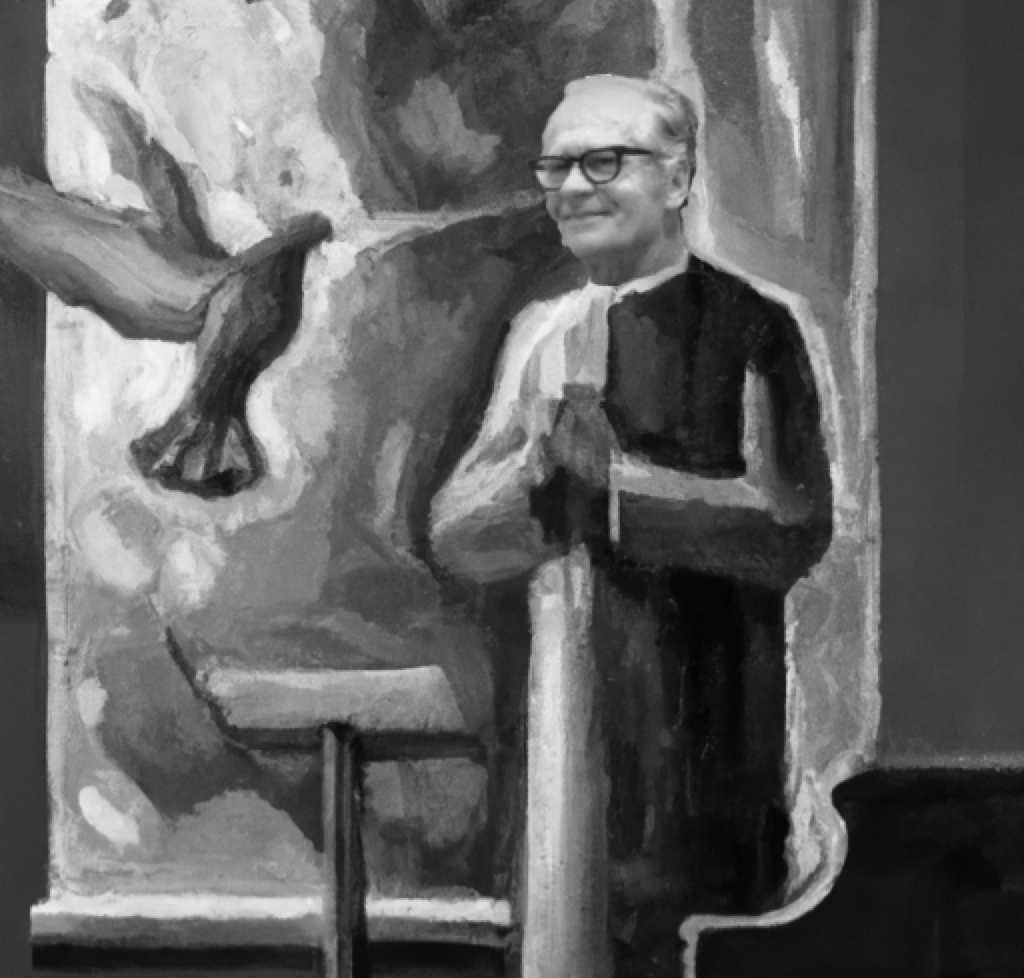

Contrary to my critic’s overly-generous assessment, there actually are no depths to which I won’t sink. To prove it, here’s a reimagining of not only Baer (aka Tin Man) but also, from left to right, Montrose Wolf, Betty Hart (whose work I especially admire), and Todd Risley [see Postscripts 4 and 5].

No doubt this blasphemy is raising your blood pressure right now… perhaps it’s so searingly impious that it’s melting the very eyeballs out of your face!

The horror! Make it stop!

But while you prepare to unleash the social media hounds on me [see Postscript 3], can we talk a bit about what makes this image appalling or offensive, if indeed it strikes you that way?

Let’s start by considering what changed in the science of behavior in that instant between when you opened this post and when you gazed at the illustration. Nothing. The amazing accomplishments of the people I depicted remain what they have always been, even if I posted an insipid graphic that may not be… dignified. The only thing new is that you now have a better grasp of my lowbrow sense of humor. With that and an old newspaper, you can wrap a fish.

Yet somehow throw-away silliness like this still evokes emotional responses. It treads upon a deep-seated desire to show reverence to people whose accomplishments we value.

And, boy, do we love to revere! We dedicate books and journal articles to our idols. We name scholarships and foundations and buildings after them. We buy t-shirts and mugs emblazoned with their likenesses. We quote them ad nauseum. If they are alive, we give them awards. If they have passed, we put their names on awards that we give to other people. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that, when we speak of these individuals, we whisper their names in a worshipful tone normally reserved for the Lord God Almighty.

This is, to say the least, a most interesting problem in behavior! It’s clear that our reverence isn’t a way to reinforce worthy actions, because the subjects of our devotion, in the present case and many others, are no longer around to appreciate the accolades. For the same reason, clearly we’re not concerned that something like my illustration will hurt their feelings. So there’s something else going on, and it points to one way in which it’s just incredibly difficult to think like a behavior analyst — even for well trained behavior analysts.

Speaking of idols, one of my all-time favorite B.F. Skinner papers is “A Lecture On ‘Having’ a Poem” (in Cumulative Record). It accentuates a point laid out in Beyond Freedom and Dignity, Science and Human Behavior, and elsewhere:

There is a sense in which having a poem is like having a baby, and in that sense I am in labor; I am having a lecture. In it I intend to raise the question of whether I am responsible for what I am saying, whether I am actually originating anything, and to what extent I deserve credit or blame.

Credit and blame…. This is the theme of “personal responsibility” and its place in a deterministic-contextualistic science that points to environmental experience as the shaper of behavior. In pure behavioristic thinking, there is no place for the “self” as an initiating agent. People don’t plan and create their behavior… they are the nexus in which many events in a behavioral history combine to synthesize something that can be emergent and new… just not self initiated. Even when our private verbal events set a course for future action (i.e., we “choose” or “decide” or engage in problem solving), they do so only because of a behavioral history that set those private behaviors into motion [see Postscript 2]. Thus, there is no “self” in the classical sense, and without a self there can be no self-determination.

In “On Having a Poem,” Skinner points out that people don’t assign “credit” to a woman for giving birth in the same way that they might, for instance, to someone writing a classic poem. There are poetry contests and high-profile “best poem” awards, but as far as I’m aware, there are no “best birthing” awards.

…Although Dan Polcari of my high school wrestling team was one of 15 kids, so if there is a “best birthing” award I don’t know about, please nominate his mom. And btw, I’ve SEEN someone give birth, and they definitely should hand out medals for that.

What’s the difference between giving birth and writing a poem? We understand the biological processes of conception and gestation, so it’s obvious that when the right variables come together, a baby can eventually result. We’re all intuitive determinists at some level, so if biology is obviously doing the heavy lifting, we don’t laud the person in whose uterus the baby grew.

By contrast, humans have a much hazier grasp of how behavior forms, so when a great poem “pops out,” it feels rather magical (especially when the creative process seems virtually instantaneous; see inset). Still, the intuitive determinist in us craves a cause, so, since the only potential “causal agent” in our line of vision is the poem’s author, that’s where we assign the credit [see Postscript 2].

…Oh, and since AUTHORS are people too, they have the same perceptual biases as everyone else, and therefore tend to tell the same kinds of tales about where their work came from. When writing one of these blog posts, for instance, I am sometimes surprised by what “pops out” (see Skinner’s, “How to discover what you have to say” and Stephen King’s On Writing). If, as a reader, I really enjoy the post, I puff out my chest in pride over the magic that “I” have just created — even though, at a rational level, I know this is complete hogwash.

The preceding is part of Radical Behaviorism 101 (though not necessarily unique to behaviorism). It’s something drilled into us from the first moment we’re told that, “The organism is always right.” Good behavior analysts totally get the message — up to a point. When, for instance, a child’s behavior harms the child or others, we don’t dispense blame and retribution. We ask what circumstances created the behavior and look for ways to enhance the environment (i.e., teach more beneficial replacement behaviors).

Where we get caught up, where we are oddly inconsistent, is when credit is in the mix. If you’re a good Skinnerian, you absolutely should try to reinforce desirable behavior. You absolutely should try to teach yourself, and others, that same behavior. But it’s simply not logical to lionize a person as some kind of magician who can sidestep the laws of Nature to conjure admirable behavior out of thin air.

Which brings us back to the Famous Behavior Analyst and my supposed disrespect thereof. In behavioral terms, what does it mean to “disrespect a person”? Yes, “disrespect” can be operationalized — this comes down to things we do to or in reference to others — but in behavioral terms, a “person” is an assemblage of behavioral repertoires. Can you “disrespect” behaviors? And if you do, do they care?

At this juncture, let’s go ahead and, in the immortal words of a great philosopher, “say the quiet part loud.” Something that everyone in behavior analysis notices but few tact publicly is that there is a whole lot of hero worship in our discipline… veritable cult-of-personality stuff [see Postscript 6] in which accomplished individuals are canonized and worshipped as infallible saints. From this arises tribes of apostles (insert your own example tribes here; off the cuff I can name at least a dozen of ’em) who tend to distrust, ignore, or even dislike one another, in part because opposing tribes never adequately adore each other’s preferred saint.

Why we do this is curious indeed, given how far it departs from our discipline’s mantra that, “It’s the behavior, stupid.” I suspect the roots of this go so far back in our species’ evolutionary history that it’s hard to overcome our base tendencies with logic and reason. We hominins began as small roving groups who competed with other groups and might even perish at their hands, so it was critical to our species’ survival to recognize and value in-group peers while keeping out-groupers at arm’s distance. So perhaps we’re built for that? Also, most primate groups tend to operate within a dominance hierarchy, so perhaps it comes naturally to us to elevate selected individuals as objects of worship. And when outsiders lob the contemporary verbal equivalent of a spear at our fearless leader, well, of course we feel compelled to mount a defense.

Although a metaphorical spear like my stupid Oz illustration causes zero measurable harm, we may respond as if it does — as if the amazing behaviors a cherished individual emitted were somehow diminished. But this is only one manifestation of the general tendency for people who are philosophically opposed to the concept of blame to liberally hand out person-focused credit. And, folks, I’m not immune to this tendency. I’ve written a number of posts about accomplished behavior analysts and, even though I’ve made a conscious effort to highlight their admirable behaviors (e.g., see here), if you inspect those posts you’ll catch me occasionally slipping into hero-worship mode. We almost can’t help ourselves.

To be sure, there are waaaaay worse sins than saying good things about people! Except insofar as doing so fuels tribal conflict and, worse, leads us away from what our science teaches us. The blessing of a successful science is that it gives us a way to understand all of behavior. The curse is that science demands consistency of perspective. You can’t apply behavior principles where you feel like it but ignore them otherwise — at least not if you’re a real behavior analyst.

To be consistent with my own message, I must point out that, like everything people do, how readers respond to my blog posts is no occasion for me to assign credit or blame. Each reaction is merely what a behavioral history makes possible in a given situational context and, as a behaviorist, how can I not be okay with that?

…Aside to my Critic: A sincere thank you for getting me thinking! I know you’re probably horrified to realize that YOU made this disrespectful post happen, but perhaps Postscript 7 will offer some solace.

I guess the really interesting question to be posed concerns what kind of behavioral history one needs to get past hero worship and truly focus on behavior. We seem to be a long way from figuring that out.

Postscripts

- Flex your logic chops! The present discussion illustrates why it’s useful to stay sharp on the basic tenets of what we call behaviorism. This is something that’s not often forced upon us in day-to-day life. The truth is, when you’re designing experiments or treatment plans, you’re borrowing strategies that originally were shaped by philosophical principles but have been ritualized to the point where you don’t need to be philosophically sophisticated to use them. Put another way, our designs and treatment plans help to protect us from sloppy thinking, and that works fine in familiar circumstances for which time-tested protocols are available. But turn your attention to new problems and logical discipline needs to come from somewhere else. As luck would have it, ABAI is hosting a Theory & Philosophy conference this October 28-29 in Chicago, with options for both in-person and remote attendance. At this writing, registration is still open. This is an opportunity to stretch yourself a bit and to engage with other people who are concerned with disciplined thinking about all things behavior. It’s good and necessary practice, no matter what your day job.

- Why people appear to be autonomous. As Skinner pointed out, one way to parse the problem at hand is that, even if logically there is no initiating self, it sure as heck feels like there is when we observe others or even our own person. I’ve found it helpful to think about behavior and the initiating self as an autopoieitic system. The language people use to talk about autopoiesis is often convoluted so let me explain with an example. Lightning has ignited a small brush fire. As the fire consumes fuel where it began, it grows bigger, allowing the wind to blow it to new areas where there’s fuel. As it grows bigger it gets hotter, so that it can now ignite fuel that’s farther away. You might say, metaphorically, that once the fire gets started it “seeks out” what it needs to maintain and grow. That’s an autopoietic system. But that system isn’t self initiating: In this case, external energy from the lightning is what started the system into motion. The system simply has properties that tend to put it into contact with fuel. Behavior is like that. It requires external influence to get it going, but thereafter gets stronger in ways that may cause it bump into additional reinforcement. A simple example: Teaching kids to recruit praise is a compound of two skills, doing “something good” and altering others to it in appropriate ways. This starts with external influences (shaping and reinforcement) but quickly becomes self-sustaining, making both component classes of behavior stronger and long-lasting.

- Cancel culture. Closely related to the present discussion is the matter of how we evaluate historical figures whose contributions are… mixed. In these days of neurodiversity political correctness, a favorite whipping boy is Ivar lovaas, who gave us not only a model for effective positive-reinforcement-based early autism intervention but also, at earlier stages of his career, extremely cringey interventions involving corporal punishment and attempted gender-role reassignment. The logic of some neurodiversity advocates has been that, because Lovaas was guilty of some pretty awful things, contemporary ABA, which owes much to him, must also be pretty awful too. In drawing this conclusion, ABA’s critics maybe factually incorrect, but they are just forming stimulus relations as Nature designed them to. They are also applying the faulty logic of personal responsibility, in which people deserve credit or blame. If you examine Lovaas through the lens of “On having a Poem,” you understand that when his learning history intermingled with his circumstances, what “popped out” was sometimes noble, sometimes misguided. Designing interventions is behavior, and as every behavior analyst knows, every person is the point of origin of both “better” and “worse” behaviors. What’s called cancel culture, therefore, is a manifestation of the myth of personal responsibility, but more than that, it’s confusing. After all, is it okay to enjoy Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs even though Walt Disney may have had a racist/sexist/anti-semitic streak (not to mention that his writers failed to employ a more sensitive title like Snow White and the Seven Little People)? The thing is, as every behavior analyst should already understand, when you evaluate behaviors (some “better” and some “worse”) rather than people, you avoid this kind of conundrum.

- On thematic coherence. In the Wizard of Oz image, I really, really wanted to include Jack Michael as Toto (and I still laugh out loud when I picture that mischievous Michael-mutt slipping out of evil old Elvira Gulch’s bicycle basket). But had I gone that route, we wouldn’t be in completely in Kansas anymore (Michael was a UCLA grad and worked at Arizona and Western Michigan).

- Acknowledgement. In the Credit/Blame Where It Is Due Department: The Wizard of Oz theme is not entirely my demented fever dream. Many years ago, something fairly similar was the conceit of an ABAI Presidential Address that, let’s just say, nobody who was there is likely to forget.

- Cults. For one behavioral interpretation, see the Spring/Fall 2024 issue of Journal of Behaviorology, which should be online soon.

- Olive branch. In the interest of good collegial relations, if a bit of blaming will make anyone I’ve offended feel better, I’m willing to pose for creation of a Tom Critchfield voodoo doll (Who knew that a whole slew of Etsy vendors make custom voodoo dolls? Philosophical considerations about credit and blame notwithstanding, I love the internet.).

replace Betty Hart with Beth Sulzer-Azaroff and I’ll watch your weird movie