Lessons from 2022’s Most Reviled Behavior Analysis Article

In previous posts I have stressed that it’s critical for members of the public to notice and value the good work behavior analysts do. To know whether this is happening, it’s critical for behavior analysts to to actively monitor this kind attention, even when it comes from sources, like social media, that don’t exactly ooze scientific credibility. Non-scholarly attention is one way society votes on the social validity of research, and researchers should have a realistic appraisal of how valued their work really is.

I’ve enjoyed sharing some success stories of dissemination impact that may hold clues about the kind of work, and style of communication, that society appreciates. Now, however, we will take a stroll through the Twilight Zone and discuss what it looks like when dissemination goes off the rails.

A Torrential Tweetstorm

In 2022 my colleagues and I published a paper called, “ABA from A to Z: Behavior Science Applied to 350 Domains of Socially Significant Behavior.” We wanted to describe as many different domains of application as we could in which someone took up the mantle of “Do good, take data.” And it took us about 4 years to compile that many domains, but we thought the effort well worthwhile in order to showcase the incredible reach and flexibility of applied behavior analysis (ABA). We expected that the paper would attract some attention because there is really no other resource quite like it.

Imagine our pleasure, therefore, when the paper’s Altmetric Attention Score (which measures non-scholarly attention received by scholarly publications) skyrocketed upward until, only a few short weeks after publication, it reached the 99th percentile among more than 240 million articles tracked in the Altmetric.com database. We were especially pleased that most of this attention came in the form of over 200 mentions, or tweets, in the micro-blogging site Twitter (now called “X”). This was the most tweets for any behavior analysis article of 2022, and this thrilled us because Twitter is “everyman” territory. Most Twitter users are regular people, not scientists or practitioners, so we thought we were living the dissemination-impact dream, bringing happy news of ABA to the masses.

Yet every social media user knows you can’t just count mentions. You have to monitor what is actually said. When we peeked under the hood of our shiny numbers, what we found (at left) was alarming. Yes, right after the article’s publication a number of tweets mentioned it rather positively (green). But starting only about a week later we began to see bursts of caustic tweets (red) referring to the article as an example of “abuse” and “torture” and to ABA as “an imperialist cult.”

Yet every social media user knows you can’t just count mentions. You have to monitor what is actually said. When we peeked under the hood of our shiny numbers, what we found (at left) was alarming. Yes, right after the article’s publication a number of tweets mentioned it rather positively (green). But starting only about a week later we began to see bursts of caustic tweets (red) referring to the article as an example of “abuse” and “torture” and to ABA as “an imperialist cult.”

What the hell?

Eventually the negative posts outnumbered the positive ones (see graph). And although twitter attention for journal articles normally abates after a few weeks, the negative ones showed staying power, with little bursts of unwanted attention continuing to erupt for long after the positive tweets had essentially ceased.

Although my “A to Z” co-authors are a smart bunch who have been around the block of behavior analysis a few times, none of us saw this coming. Yet what happened to us is far from the worst outcome a scientist has experienced on social media. Ultimately we were left feeling bewildered and not a little bit scared. Here’s a reaction from my co-author Derek Reed:

I was honestly surprised by the attack… The content of the paper is all about the various ways ABA can be used in “everyday” contexts and applications—specifically, beyond autism. I repeat: Specifically. Beyond. Autism. The ad hominem attacks on me were, of course, discouraging, but more troubling was the accusations that I “abuse children” and “support torture.” As a credentialed and licensed behavior analyst, such accusations could result in investigation and a host of potential regulatory problems. As the parent of a child with autism, I was particularly upset that the respondents jumped to conclusions about my stance on particular aspects of ABA.

All in all, I’m pretty sure that no other ABA-related article from 2022 got such rough treatment in social media. The question, of course, is WHY this happened to a paper that my co-authors and I never imagined as controversial.

The answer may say more about the societal milieu that ABA inhabits than about our article per se. The fact is that over the years ABA has spawned a few controversial practices, such as gender-role reassignment “therapy” and the use of electric shock and slapping as punishment. But behavior analysts know that these were a tiny fraction of what developed in ABA, and for the most part these practices were short lived because early applied behavior analysts rejected them as unethical and/or ineffective. By any objective assessment these were unfortunate historical mis-steps in the evolution of a valuable discipline.

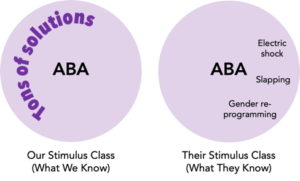

To most of us, then, ABA means scores of effective, humane, reinforcement-based interventions that have contributed to making so many lives better (below, left side). As Derek mentioned, that is what the “A to Z” paper emphasized. It made no reference to punishment or any other touchy subject. Clearly, then, the tweetstorm wasn’t a response to our article’s content. Rather, the bone of contention seemed to be the general concept of ABA, which we had the misfortune to mention in our title. In fact, I suspect that publishing a blank page with “ABA” for a title might have evoked a similar response. The question then becomes: Why would this simple acronym elicit such venom?

People Know What They Know

Here some theory of mind is required. Remember that most people lack our detailed understanding of behavior analysis, in part because as a discipline we have not always been proactive or savvy when it comes to explaining what we do and why it’s vital. Now and again, however, somebody on the outside will stumble onto one of ABA’s unfortunate mis-steps and become appropriately appalled. They tell some other people, and in a digital world where ideas can go instantly viral, pretty soon a lot of people are in on the conversation. But remember, since these people don’t know a lot else about ABA upfront, their conception of it is colored heavily by those atypical examples. In the diagram below (right side), theirs is a stimulus class that virtually forms itself.

This isn’t new. ABA has attracted criticism since before it even existed, as some reviewers thought that the behaviorally engineered world of Skinner’s utopian novel Walden Two would be “intolerable” or worse. Once ABA got going, things did not improve. In the 1970s “behavior modification” reminded some people of brainwashing in the film Clockwork Orange. In the 1990s it was popular to equate reinforcement with bribes. More recently, the use of electric-shock as punishment by a few practitioners has been in the spotlight, so much that it was the subject of most of the June, 2023, issue of Perspectives on Behavior Science. None of this helps to persuade skeptics of ABA’s good intentions and prosocial goals.

Fuel on the Flames

And that is true even without an internet. The rapid flow of electronic information has created a marketing challenge of a whole new magnitude. For instance, at the time I wrote this, Paragraph 2 of the Wikipedia entry for “Association for Behavior Analysis International” read:

ABAI has been criticized for its connections to the Judge Rotenberg Center (JRC), a school that has been condemned by the United Nations for torture. According to the Autistic Self Advocacy Network … ABAI has endorsed the methods of the JRC, including its use of … a device that delivers painful electric skin shocks, by allowing them to present at ABAI’s annual conferences.

Yikes. This (“torture” and “painful electric shocks”) is what an uninformed a reader would encounter before learning about any of ABAI’s many prosocial contributions, which don’t pop up till Wikipedia’s Paragraph 3.

Adding even more fuel to the fire in recent years: An outspoken neurodiversity community. Before doing anything else, I want to give credit where it is due to this community. One dictionary I consulted defines neurodiversity as “the range of differences in individual brain function and behavioral traits, regarded as part of normal variation in the human population.” The neurodiversity movement demands, appropriately, the recognition that even people who qualify for a diagnosis of some sort have strengths and talents (and rights). And the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network, which was mentioned in the Wikipedia post on ABAI, has done some really important work such as combating harmful stereotypes, producing materials for persons with autism who go to college, and lobbying against harmful practices in special education. I’m 100% for all of that.

But it is also the case that some neurodiversity advocates view any intervention aimed at teaching persons with intellectual disabilities “neurotypical” skills as an insulting and disempowering quashing of diversity. A few outspoken opponents of ABA have claimed that the resulting process of “normalizing” causes serious psychological trauma. As best I can tell, all of the hostile tweets about “A to Z” originated in the neurodiversity community.

With this in mind, think of those purple bubbles in my diagram above as stimulus classes comprised of relations between “ABA” and various other things. It should be obvious that people inside and outside of behavior analysis can have very different stimulus classes encompassing the stimulus “ABA.”

And this matters because of a fundamental principle regarding stimulus classes: Two classes that share a member can spontaneously merge into a single, larger class. Thus, for people who relate “ABA” to practices that are humane and effective, the “ABA” class can merge with a larger one incorporating numerous other humane and effective practices. For people who relate “ABA” to specific painful and coercive practices, the “ABA” class can merge with a larger one incorporating numerous other painful and coercive practices.

The ABA Critic is Always Right

You might think that this is just an overly technical way of saying that first impressions matter. But I hope you can see that when people cast dark and sinister aspersions at ABA, they are only doing what behavior principles demand of them given their respective learning histories. These are the same processes that help to forge our own positive impressions of ABA.

In the words of political strategist Frank Luntz, this is a classic case of “it’s not what you say, it’s what people hear.” That’s the subtitle of his highly recommended book, Words that work, which is a non-technical exploration of how people can understand words in different ways. If what a person knows indicates that ABA is equivalent to torture and abuse, well, it’s impossible for that person to see it otherwise

So, the thing on which to dwell is not that first impressions matter, but rather why they matter: Because they are the first in a chain of potential stimulus-relations dominos that can make a bad first impression so much worse. The echo-chamber world of social media only magnifies the problem because one person’s derived stimulus relations can be effortlessly transmitted to many others.

A Reckoning is Coming

This raises a key point. Although the number of people taking the lead on neurodiversity-driven criticism of ABA may be small, their audience is not. Last I checked, the Twitter users who disparaged the “A to Z” article had a combined total of about 178,000 followers. This kind of reach makes it possible for even minority views to seep into the public consciousness. Again, Derek Reed:

I am currently teaching Introduction to Behavior Analysis and for the first time ever I have had students vocalize — in front of 180 other students — that ABA is abusive, wrong, and evil. I don’t know how many others share those thoughts but simply haven’t vocalized it. But now I’ve been doing damage control all semester, in the hope that students don’t leave the course assuming these accusations are true. Keep in mind, this is at Kansas, in a very behavior analysis friendly department. More and more I hear others’ stories of how random people share concerns about ABA when they find out the colleague is a behavior analyst. This isn’t going away. It’s festering and I fear a reckoning is coming. We can’t just keep willing the problem to disappear.

I have had the same experience recently with students arriving in my classes already predisposed against ABA. During the most recent semester this included a woman who quit her job as a Registered Behavior Technician, which she initially enjoyed, after learning (presumably online) that she was helping to perpetrate “abuse.”

A study by Saar and colleagues (2023) on ABA-related posts on the social media platform Reddit provides a glimpse into how widespread this problem might be. The study examined roughly 1000 posts that expressed a pro- or anti-ABA opinion, finding that more than half were anti-ABA, with the most common criticism being that ABA is abusive in the conformity-enforcing sense touted by the neurodiversity community. Among posters who identified their role as stakeholders, about one-third of parents and professionals endorsed an anti-ABA stance. Almost four out of every five posters with autism spectrum disorder were anti-ABA.

An Ounce of Prevention

The thorny question raised by all of this is what in the world can be done to burnish ABA’s public reputation. Some good news is that stimulus classes are not forever: Given the right experiences they can be modified. This means that people who have concluded that ABA is “torture” and “abuse” don’t necessarily have to think this way forever.

One of my favorite examples of how corrective measures operate was in a series of articles by University of Illinois Chicago’s Mark Dixon, who demonstrated the kind of stimulus-relations experiences Americans would need in order to project less prejudice toward people of Middle Eastern descent. But there’s also bad news: It can be easier to create than dismantle stimulus classes , that is, once stimulus classes form they are resistant to change. The available evidence, therefore, suggests that you may not get a second chance to make a good first impression.

The better alternative is to discourage ABA-hostile stimulus classes from forming in the first place by creating ABA-friendly stimulus classes. As my ever-upbeat “A to Z” co-author Bill Heward often reminds me, all posts on the “A to Z” article from people who know behavior analysis were positive. It follows, perhaps, that if more behavior analysts were posting more effectively on social media, then lots of people would get to know ABA through its many prosocial, non-abusive, non-coercive contributions. This would place ABA into desirable stimulus classes that would be hard for occasional critics, like those in the neurodiversity community, to perturb.

We behavior analysts are all guilty of doing too little to create those critical positive first impressions. Consider my co-authors and I. Once the “A to Z” article was published we did tweet about it, but our single post was boringly informational (we simply announced that the article was out). We failed to harness any of the features that make social media posts eye-catching to everyday people, such as:

- Talk about solutions to problems that affect large segments of the population

- Emphasize issues already prominent in the news or on social media

- Report surprising or counterintuitive findings

- Focus on social justice issues

- Draw connections with the values and agendas of special-interest groups that are active in social media

Folks, the “A to Z” author team of Heward, Critchfield, Detrich, Reed, and Kimball are not victims. We dropped the promotional ball and our article paid a steep price in the currency of social media chaos. Instead of passively hoping for positive attention, we could have actively crafted a series of social media posts focusing on the many things ABA is good for that would people those who know only about its role in autism. We could have partnered with pro-ABA groups of parents and professionals to generate far more positive attention than we got from the autism community. And so forth. I’m not saying that these steps would have prevented the hostile posts we attracted, only that had we done our jobs right a hundred or so shouts of “abuse” and “torture” could have been overwhelmed by positive commentary, thereby appearing to be precisely what they are: the subjective impressions of a poorly-informed minority. Context is everything, even in social media, and good dissemination means creating a societal context in which our contributions can be appreciated.