Pioneers is a series of occasional posts celebrating people

who helped to make behavior analysis what it is.

Guest posts are always invited.

Contact Tom Critchfield (tscritc@ilstu.edu) with your idea.

PREVIOUS POSTS IN THIS SERIES:

PREMISE: Contemporary behavior analysis is big and diverse. We got here through the efforts of people with crazy competence, persistence, and creativity, and valuable lessons can be learned by examining how they made possible our discipline’s hard-won advances. Posts in the Pioneers series elaborate on their contributions, hopefully in a way that provides food for thought about how to approach our own lives and careers.

Because our discipline so big and diverse, no one is fluent with all of it. One particular goal of Pioneers posts is to highlight people who might be iconic in one specialty area but unknown in others. Elsewhere I’ve emphasized the benefits of knowing about a ton of different things. One of the best ways to understand an area outside of your own, and to find connections to your interests, is to see how that area came to be in the first place. Look to people like those described in these posts for insights.

One of a Kind

If you met Ogden Lindsley (1922-2004), you remembered him.

There was his tall, athletic frame… the perfectly-fitting suit, sometimes in a daring plaid that most men couldn’t pull off… and the ubiquitous bow tie that on Og didn’t seem a bit nerdy. There was the mile-wide smile and the manicured whiskers that gave him a mischievous aura (and always reminded me of “Old Scratch” as portrayed in one of the best-ever Twilight Zone episodes; check it out and see if you agree)

And then there was the room-sized personality. Og laughed often, was prone to breaking out in song, and was happy to render a pointed opinion on just about anything (he was definitely among those who may be right, may be wrong, but are never in doubt).

To complement the colorful demeanor, there was a colorful life story, full of twists and turns which included, among many other things, a case of “reports of my death are greatly exaggerated” (he was erroneously declared killed in action during World War II and his name appears on a Rhode Island monument to fallen soldiers). All in all, when I think of Og’s vibe, I can’t help but recall a boisterous old ad campaign that featured “The Most Interesting Man in the World” (here’s one installment).

Og commanded attention, and where you found him you found a coterie of rapt admirers. With Og, there was always a risk of the legend overshadowing the man, something worth exploring as we approach the 20th anniversary (October 10) of his passing. A lot of people remember the flamboyant persona that Og cultivated, but it’s the life of twists and turns that most interests me.

The whole conceit of the “Something Interesting” blog section is that, as Skinner told us, life’s twists and turns present opportunities, so when something interesting comes along, you should follow where it leads. If you are observant and persistent, nature will reveal its secrets. In a previous post, I wrote about how people who fit Skinner’s description are especially good at recognizing “something interesting” when it appears, and thus tend to make contributions in more than one area. That certainly describes Og Lindsley. But I won’t attempt a full biography here (if you’re interested in that, check out this obituary in American Psychologist and this list of Lindsley’s papers).

Instead, I’ll recommend two brief-but-informative reads addressing very different phases of Lindsley’s career.

At the Mountains of Madness: The First Human Operant Lab

When Walden Two came out in 1949, and Science and Human Behavior came out in 1953, their extensions of operant principles to humans were highly speculative. There was no applied behavior analysis to speak of and in fact only sketchy evidence in humans of the rock-solid operant processes that had been demonstrated in animals.

I have written in previous posts about the value of being broadly educated. People with diverse skills and knowledge see opportunities that others might not. Lindsley, of course, studied under Skinner at Harvard and so of course he was influenced by the famous Harvard Pigeon Lab. But he had a rather eclectic academic background prior to graduate school (including some engineering, chemistry, and psychology), not to mention diverse experiences in the military, including as a trainer/instructor.

Even in grad school, Lindsley was interested in seeing what operant analyses could reveal about humans, both typical and otherwise. Or maybe the better worrd is “impatient”

He was livid, for instance, that so many people had used air cribs without taking advantage of the opportunity to collect systematic data from their babies (reported by Alexandra Rutherford in Beyond the Box: Skinner’s Technology of Behaviour from Laboratory to Life, 1950s to 1970s). So he connected a cumulative recorder to daughter’s, resulting in the first cumulative record of human operant behavior presented at a scientific meeting (Eastern Psychological Association, circa 1951). [BTW, if anyone out there has a copy, I’d love to see it!]

Following many conversations between Lindsley and Skinner, a grant was secured to establish a human operant laboratory at a state mental hospital near Boston, starting in the early ’50s. Now, you might think that because laboratory research had already been conducted with many different species it would be easy to figure out how to study one more. Not so. Humans are unusual creatures and mental patients perhaps more so (for instance, Lindsley found that it took considerable ingenuity just to build a response apparatus that his participants couldn’t break).

Please don’t prejudge! You might not think a story on the theme of “building a lab” could be engaging, but a lot of important things flowed from this grant project.

- The grant helped to set the stage for the experimental analysis of human behavior (EAHB). Today we take for granted at EAHB is an integral part of the experimental analysis of behavior but that wasn’t always necessarily so. Through at least the 1990s hard questions were being asked about whether human studies could really reveal fundamental principles. Lindsley provided encouraging early evidence that perhaps they could.

- It’s not trivial that that the grant discovered orderly behavior in humans who were considered so “disorderly” that they had to be institutionalized. This helped to set the stage for the development of behavior therapy (Lindsley coined the term), in which “abnormal” behavior is viewed as the product of “normal” processes. And, of course, applied behavior analysis has the same North Star.

- Lindsley was one of the first to appreciate that verbal and social behaviors may be “uniquely human” and thus require special study. In grad school, with Nate Azrin, he conducted possibly the first study on reinforcement of human social behavior. The grant included a focus on disordered verbal behavior, and, as mentioned in the blog post, it demonstrated that delivering reinforcement to another individual could function as a reinforcer.

- Lindsley’s work evaluated behavior in “altered states” created by physiological processes (sleep) and external agents (drugs). In this sense, it anticipated behavioral medicine and human behavioral pharmacology, two areas of research and application that have contributed significantly to human well-being.

- The grant marked an early transition toward single-case experimental designs that are considered foundational in our discipline today. Those designs simply hadn’t been formalized in the 1950s, and as the blog post discusses, you can see in the grant Lindsley wrestling with some of the issues that would come to shape our preferred designs.

Check out the blog post for a peek at some of the halting first steps toward the creation of modern behavioral research.

Revolution in the Making: Behavioral Technology for Everyone

Lindsley’s experience as a military instructor stuck with him, and of course he was also aware of Skinner’s early explorations of teaching technology. In 1964, Lindsley recorded some preliminary thoughts on how behavioral expertise could be useful in what today is called special education. As had Skinner in Technology of Teaching, Lindsley mostly emphasized how a behavior analyst could improve upon traditional instruction.

I’ll confess that I’m not a giant fan of most of this paper. Its tone is one familiar in academic circles: Brilliant outside expert looks to rescue (but simultaneously assume control over) work that others are already struggling with. That’s intellectual colonialism, not dissemination (For example, not just anyone could construct a teaching machine or the Skinnerian instructional sequences that they employed. And much of the behavioral expertise that Lindsley originally saw as relevant to special education required advanced training).

But a brief passage in the 1964 article foreshadows a revolutionary pivot that would define the last 40 years or so of Lindsley’s professional life.

[Behavior analysis] can provide a practical tool for helping special educators and vocational rehabilitors [sic] to increase the efficiency of their education, training, and management of [student] behavior. In this new approach the educator or rehabilitator [sic] does not assume the role of playmate, custodian, policeman, or even sophisticated clinician. Instead, his role is that of a specialist in… behavior. He arranges the classroom, home, or institutional environment so that the children can play with each other and maintain their own personal dignity and deportment. [emphasis added]

Note two things about this comment. First, long before special education law forbade the institutional warehousing of persons with disabilities, Lindsley foresaw a “student first” future defined by the needs and progress of the individual. This would become a guiding principle in his view of education for all kinds of learners.

Second, perhaps because Lindsley himself had worked as an instructor, this passage suggests, not how behavioral technology can supplant those who are failing in the applied trenches, but rather how technology might empower those people to be more effective. Indeed, rather than derogate their efforts, Lindsley honored their motivation to be better.

The current training, motivation, and philosophy of special educators and vocational rehabilitators are ideal for operant prosthetic methods. Their concern is with the children and their behavior. Their interests are practical, and their needs immediate and direct. [emphasis added]

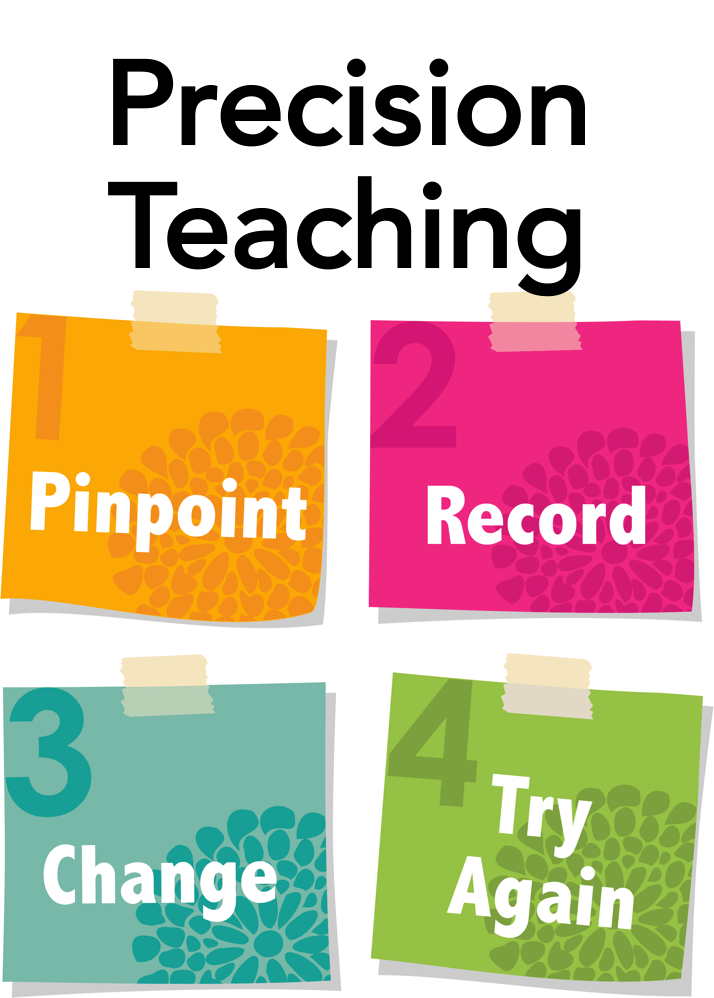

The rest of the 1964 paper is hyper-technical and heavy with jargon, but going forward Lindsley refined and accentuated the twin realities that (a) someone other than a behavior analyst does the heavy lifting in most instruction and (b) their interests are practical. Those notions guided Lindsley’s creation of Precision Teaching (PT), which began taking shape in the 1960s and 1970s and which Lindsley tirelessly promoted thereafter.

Briefly, according to West et al. (1995), “Precision Teaching is not so much a method of instruction as it is a precise and systematic method of evaluating instructional tactics and curricula.” Lindsley himself called PT “mostly a monitoring, practice, and decision making system [that] combines powerfully with any curriculum approach.” PT’s core ideas are to (precisely) pinpoint educationally useful behaviors, to arrange lots of opportunities for them to occur, and to (precisely) measure the result. A lot else could be said about PT, but those are revolutionary precepts when you consider how often traditional education is vague about what’s being taught, leaves students doing next to nothing, and dodges objective accountability for student progress.

Even more revolutionary, however, is that from the beginning PT was developed with the idea that it would be taught to and used by people in the trenches of education. Lindsley believed that people who care about students will find ways to help them if they have objective, real-time feedback on what is and isn’t working. PT was designed to let teachers, and even students, seek out their own high-quality feedback.

In this focus on designing interventions expressly for dissemination and natural-environment implementation, Lindsley was decades ahead of his time. One of the standard complaints of behavior analysts — tracing all the way back to Skinner and continuing today — is that they can devise amazing behavioral technology that nobody seems to value. But that technology is often cumbersome to use — It’s complicated, it requires training that non-behavior-analysts can’t acquire quickly, it doesn’t fit comfortably into existing systems and daily routines, and it’s explained using words people don’t understand.

PT, by contrast, was intended to be something that could be talked about in simple language, that could dovetail with any instructional environment, and that didn’t require an advanced degree in behavior analysis to implement. In this regard, contemporary applied behavior analysis still has a lot to learn from Lindsley.

Here’s the context for the second recommended article. For years Ohio State University has run a graduate behavior analysis seminar featuring distinguished guests who participate remotely, early on via teleconferencing and later via video conferencing. The guests discuss their interests and engage in freeform give-and-take with students. Bill Heward recorded many of these dynamic sessions and is now, with Jonathan Kimball, leading an effort to transcribe them and preserve them in print. John Eshleman helped with the Lindsley installment, about which I’ll say: Og may or may not have been “The Most Interesting Man in the World,” but in this article you’ll see him at the height of his colorful, charismatic, and sometimes controversial powers. Definitely worth a read.

Postscript: Yet Another Career

After this post dropped, Dan Hantula wrote to mention that Lindsley had another interesting career phase, in advertising. To wit:

While Watson first brought behaviorism into consumer behavior, its influence was not evident in empirical research until the 1960s when Lindsley (1962) applied operant theory and techniques to studies of consumer behavior. In a typical study of this type, a participant was placed in a comfortable air-conditioned room with a television receiver in front of the viewer, holding a small switch that produced a slight increase in the brightness of a television image when pressed according to a conjugate schedule of reinforcement. In a conjugate schedule of reinforcement the participant directly and immediately controls the intensity of a continuously available reinforcing stimulus, such as a television show. The use of conjugate reinforcement continued when advertising researchers used a device called conjugately programmed analysis of advertising (CONPAAD) to measure advertising effectiveness in terms of such variables as attention to story board and finished versions of advertisements (Nathan & Wallace, 1965); effects of satiation on advertising (Grass & Wallace, 1969); magazine article interest in an ad lib situation (Wolf, Newman, & Winters, 1969); and readership with magazine articles (Winters & Wallace, 1970). Although this methodology fell into disuse in favor of eye-tracking devices (Hantula et al., 2001), ironically, with the advent of the television remote control, consumers could perform the opposite function of this device by clicking a button to switch off a program that they did not want to vie (from DeClemente & Hantula, 2003).

Don went on to say:

He worked with an ad agency in the Philadelphia area called Arbor, Inc. Some years ago I was able to talk with a couple of the guys who worked with Og on ‘behavioral’ measures of ad attractiveness. They also got into some work on TV ads for pet food that were targeted at pets, not humans. They thought his behavioral measurement stuff was genius. At ABAI 1997 (I think) Og had coffee with me and my grad students. One student asked him why he stopped the ad work. His reply was something like …. “I was working with the ad agency (Arbor) but at the same time some large federal grants came in to Harvard to study operant behavior in schizophrenics. I was trying to keep both projects going but at the time there was more money in the lab at Harvard than at the ad agency so I chose the lab work.” He then paused, looked around the conference area, waved one of his arms, and said something like, “This (i.e., all autism all the time in ABA) is not what I hoped for…. Maybe I made the wrong choice.” He encouraged the students to keep working on behavioral stuff in consumer behavior, advertising, etc, stressing that this, rather than what ABA had become, was the future of behavioral work.