This is a followup to “The Crispy R and Form versus Function in Verbal Behavior,” (published April 24, 2024), in which I argued that behavior analysis sometimes ignores potentially important issues concerning the topography of verbal behavior.

Obvious Observation #1: With selected exceptions, behavior analysts have not been very good at talking to People Who Are Not Behavior Analysts (PWANBAs).

Obvious Observation #2: Systematic programs of research on how listeners respond to various kinds of verbal behavior are needed to guide the creation of evidence-based practices for talking to PWANBAs.

Our discipline could really benefit from an evidence-based technology of PWANBA outreach. And among the critical targets of such a technology would be first impressions, because. if PWANBAs have an instant, visceral dislike for us, well, we’re not going to get very deep into any message before we’ve lost our audience.

And, by the way, that’s exactly how some PWANBAs have responded to us in the past, the most famous example, perhaps, being Catherine Maurice‘s initial reaction to her first ABA therapist, whom she covertly nicknamed “Attila the Hun” (scary, since that particular therapist is considerably more warm and inviting than a lot of behavior analysts I know).

First impressions can hinge on manipulating motivating operations, for instance, by emphasizing the wonderful outcomes that will be created rather than the technologically sound and linguistically pure procedures which will make that happen). Or they can hinge on gut-level emotional responses to general features of the speaker or the speaker’s word choices. Importantly, you don’t need to think in terms of mands and acts and autoclitics and intraverbals, and so forth, to begin peeling back the layers of this onion.

That’s something Matt Laske, now an Assistant Professor at University of North Texas, has understood in pursuing a program of research on public speaking that he began under the tutelage of Florence DiGennaro Reed at the University of Kansas.

The ecological validity of Matt’s research should be obvious. Behavior analysts, basic and applied alike, spend a lot of time telling others about what they do and why it’s important, and much of that communication is spoken. It makes sense to figure out the conditions under which listeners will be receptive to spoken communication. Let me repeat that: Gauging the success of communication is an analysis of speaker-related independent variables and LISTENER DEPENDENT VARIABLES. Which is a very different enterprise than Skinner’s mostly speaker-focused analysis in Verbal Behavior.

For a great example of the distinction between speaker and listener behavior functions, check out political strategist Frank Luntz’s book Words that Work, which is subtitled, “It’s not what you say, it’s what people hear.” [Luntz is famous for helping the U.S. Republican Party package its platform in emotionally-appealing ways; e.g., instead of the off-putting “drilling for oil,” they speak of the exciting-sounding mission of “exploring for energy”]. Also see my November 23, 2023, post describing an article that was received very differently than its well-meaning authors intended. The take-home: What launches verbal behavior (the variables controlling composition) of is a fascinating and vital topic — but so too is how verbal behavior lands (the variables controlling listener responses).

Says Matt:

When there is a speaker, there is a listener. Therefore, we need to consider the interaction between their behaviors. I think the general consensus is that communicating our work and values relies heavily on our vocal verbal behavior as researchers and practitioners. How do we know if we are effective? Well, we need to know how the listener responded to our behavior.

As an aside, as often happens with research programs, Matt kind of stumbled into this one sort of by accident:

Skinner’s 1956 A Case Study in Scientific Method is one of my favorite papers as a researcher. One of the informal scientific principles Skinner wrote about was, “When you run onto something interesting, drop everything else and study it” (p. 223). This is what happened to me while studying public speaking. I read the work done by Dr. Raymond Miltenberger and his students about reducing speech disfluencies with public speakers (Mancuso & Miltenberger, 2016; Spieler & Miltenberger, 2017). In addition to measuring disfluencies, they also measured audience (i.e., listener) ratings of speaking effectiveness. What fascinated me in those studies is that although the speakers used fewer disfluencies following intervention, they were not consistently rated as more effective speakers by the listener. I thought to myself, “huh, maybe there are other behaviors necessary to be an effective speaker. Well, what are those behaviors?”

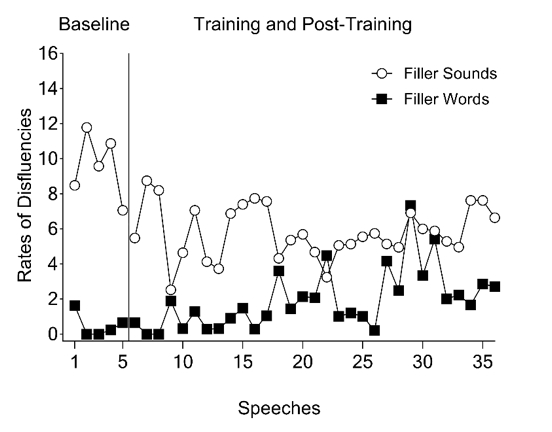

Speech disfluencies can be loosely defined as sounds and content that are not necessary to the “intended message.” They are intrusions into the flow of spoken verbal behavior that have no “content.” In his early work Matt realized that not all disfluencies are created equal. Here’s an example. In a 2022 study, an intervention was developed to reduce disfluencies during public speaking, but for one participant the results were mixed. Note how the intervention reduced the prevalence of non-word disfluencies (such as um, er, ah), but increased the rate of unneeded words (such as like).

Matt has also been careful to measure listener responses to public speaking, in part by having it rated on various dimensions by objective experts.

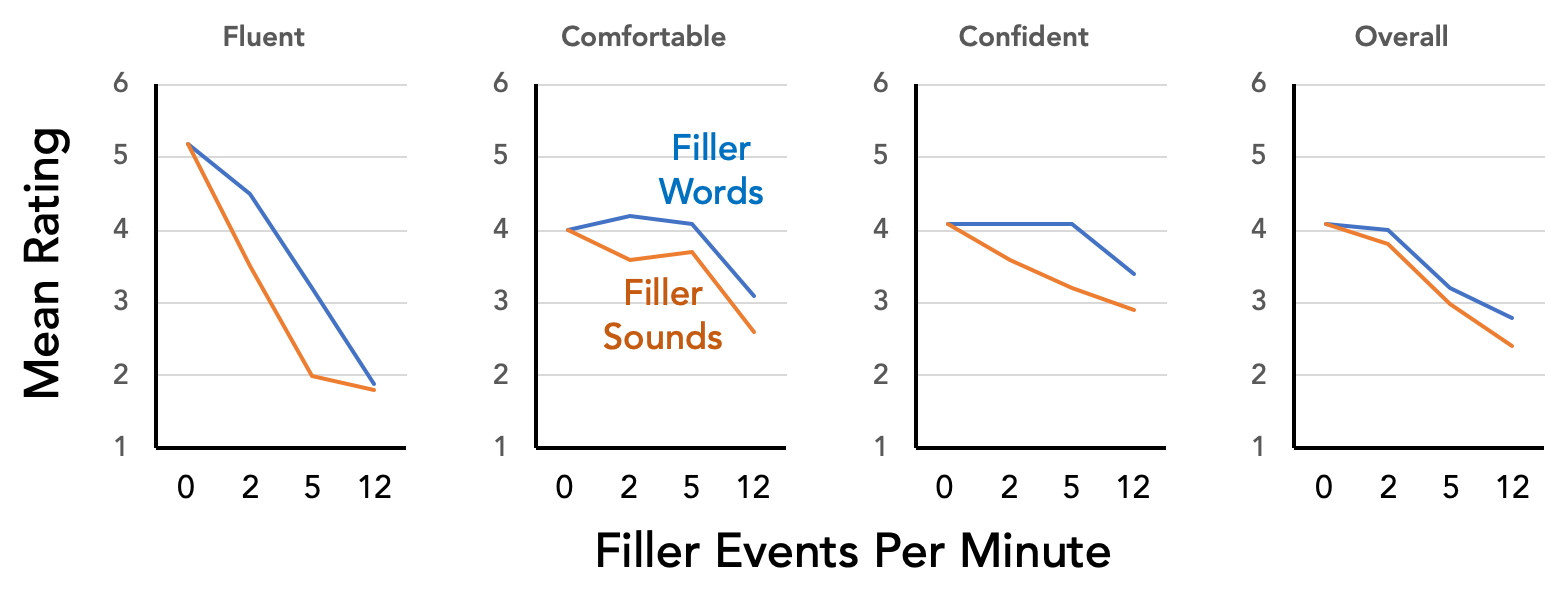

That’s enough to set you up for a highly recommended Laske and DiGennaro Reed article in Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (“Um, so, like, do speech disfluencies matter? A parametric evaluation of filler sounds and words“). The study asked a cool dose-effect question: How do different rates of two kinds of disfluencies affect listener perceptions of the speaker?

Research confederates were recorded while giving brief presentations, with their performances seeded with different rates of word and nonword disfluencies (“filler events” below). The recordings were then rated by objective “expert listeners” on a number of dimensions. See below for a sample of the findings.

Two things are evident: (a) the fewer disfluencies the better, but (b) across the board, non-word disfluencies (filler sounds) hurt listener appraisals of a speaker more than word disfluencies (filler words). What’s brilliant about this study is how it integrates a fine-grained analysis of speaker verbal topography and a fine-grained analysis of listener behavior, rather than [in Matt’s words]…

… Treat function and topography as two isolated behavior features . The function of response is important, obviously, but if we consider topographical differences as a change in stimulus conditions, now we are bringing in stimulus control and bringing in the three-term contingency. For example, there is research demonstrating that variability in a speaker’s vocal pitch influences a listener’s physiological arousal and ratings of effectiveness (Rodero, 2022). From an analysis of the speaker’s behavior, the function might be the same regardless of vocal pitch, but the topographical difference has a different function for the listener. Again, this is why I suggest that function and topography be considered together AND include the listener’s response.

Precisely. As per Skinner, you may sometimes be able to evaluate speaker behavior alone, but communication is inherently interactive. There’s no way to meaningfully examine it without looking at both speaker and listener behavior. And, with respect to “It’s not what you say, it’s what people hear,” there’s no way to understand listener behavior without a careful analysis of the topography of speaker behavior.

Yet when I opened the present post with this:

Obvious Observation #2: Systematic programs of research on how listeners respond to various kinds of verbal behavior are needed to guide the creation of evidence-based practices for talking to PWANBAs.

…I sort of lied. I don’t actually know whether the preceding is “obvious” within our discipline. Indeed, I suspect that, in the history of behavior analysis, more printed words have been devoted to bemoaning our communication failures than to formally analyzing what controls listener responses in order to support the development of evidence-based technologies of effective communication. Work like Matt’s is extremely important, therefore, and if you got hung up on the fact that the results shown above are sort of what you’d intuitively expect (fewer disfluencies = better), you’re missing the point of “evidence-based technologies.” As empiricists, we can’t say we understand listeners till we study them. Doing so will sometimes confirm suspicions and sometimes surprise us. The data will be what they will be — emphasis here on having data.

Matt is one of the few currently doing systematic research on how speaker verbal topographies affect listener perceptions of speakers and their messages. What these studies teach us will be critical in unlocking the secrets of effectively sharing behavior analysis with more and more PWANBAs. We need a lot more of this kind of research.