PREVIOUSLY IN THIS SERIES: QUEST #1

If I were to tally up all of the various frustrations that I’ve heard behavior analysts express over the years, far and away the most common is that behavior analysis, despite a rigorous natural-science foundation and ample evidence of effectiveness, gets little love from the broader culture. This problem bugged Skinner and it has bugged every generation since.

Many explanations for this problem have been suggested, and a lot of them go something like this:

People Who Are Not Behavior Analysts (PWANBAs) are too steeped in

traditional mentalistic notions to ever understand a behavioral perspective.

OR

PWANBAs won’t let go of ineffective ways of

thinking about behavior because these keep them unaccountable

for the hard work of being good behavioral engineers.

There are lots of other similar claims, but you get the basic story line: We haven’t had more societal impact because, due to audience inadequacies, this an impossible goal.

Quit Bellyachin’ and Start Disseminatin’

Hmmm…. In my very first undergraduate class on applied behavior analysis, my professor, the underappreciated Rob Hawkins (see Postscript 2), emphasized that a first step in understanding challenging behavior is to ask when/where it doesn’t occur. So, if our problem is the big societal brush-off… how do you account for the runaway success of Let Me Hear Your Voice and the resulting boom of interest in ABA for autism? What about the 7 million copies sold of Toilet Training in Less Than a Day? How about the popularity of Karen Pryor’s Don’t Shoot the Dog! and the near-viral spread of positive-reinforcement approaches among pet owners, animal trainers, and zoo personnel?

Apparently when the message is right, PWANBAs can embrace what behavior analysis has to offer.

That’s as good an introduction as I can think of to the WIDER REACH INCUBATOR, a project headed by Adam Hockman with the goal of helping behavior analysts disseminate to the public through high visibility publications. Adam has a background in instructional design and eLearning. Wider Reach is the product of a Public Awareness Grant from the Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis, whose purpose is “to support projects designed to deliver messaging focused on behavior science and behavior analytic solutions to important problems. Messaging should be grounded in scientific evidence and target an audience that has not yet been reached by existing initiatives.”

Wider Reach is currently wrapping up its first year. What I like most about the project is that it focuses on something that many previous efforts to promote dissemination of behavior analysis have not — how to craft a message that is audience-friendly (see Postscript 1).

In a series of short introductory videos on the Wider Reach site, you’ll see attention to how to identify high-interest topics; how to structure an article to sustain interest; how to craft a catchy title; and how to determine which high-impact publications are suitable for your topic. All of that is about matching the message to the audience, rather than expecting an audience to track you down and spontaneously adapt our highly technical stuff to their needs.

The Genesis of Wider Reach

When I asked Adam what compelled him to start Wider Reach, he echoed a theme sounded by the late, great Ronnie Detrich: “It is somewhat ironic that what is arguably a science of influence (behavior analysis) has not been more effective at influencing the adoption rate of a science of influence.” As Adam notes:

When I was the editor of the Standard Celeration Society, I regularly helped behavior analysts and precision teachers write for non-academic outlets. SCS had exceptional practitioners and researchers of precision teaching who could not describe what they do or how it works to the broader community. They often had a hard time figuring out what to write and when and where to do it.

This experience led Adam to want to

…Fill a gap in behavior analysis by teaching individuals and organizations how to write for mainstream content providers like consumer and trade magazines and popular websites. Most people learn about advancements in science, health, and education by reading these, not peer-reviewed academic journals.

When working with organizations (e.g., ABAI affiliate chapters), Wider Reach helps the leadership team create a strategic communication plan—the position statements, resources, blog posts, or earned media they need in order to have a broader impact. Since most affiliates are volunteer-led with limited budgets, they can’t afford consultants and marketing firms. As a result, they don’t publish enough material or the right kind of material to have influence. We help these organizations build a library of foundational publications and a plan for producing content throughout the year. We also advise on web design and social media.

Audience, Audience, Audience

Adam says that writing for effective outreach involves three things:

First, the ability to discuss the history, concepts and principles, research designs, and change procedures of behavior analysis. Writing about a topic and critically analyzing it for a reader require translating and applying the science. It’s hard to do that if you can’t talk about it.

Second, basic writing (and thinking) skills that allow you to transmit ideas clearly and logically. Sort of a combination of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style and Whimbey, Lockhead, and Narode’s Problem Solving and Comprehension.

Third, an awareness that even if you know what you’re talking about and have decent thinking and writing skills, you need someone whose thinking you trust to put a critical eye on what you’ve written.

It’s funny. Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior is nominally about speaker behavior, but you could just as easily say it’s about how audiences shape and set the occasion for speaker behavior that, in turn, is effective with the audience. Somehow, this point escapes a lot of behavior analysts when they set out to communicate with PWANBAs. Adam, for his part, conceived of Wider Reach as the result of a broad array of critical experiences.

Years ago I took Marilyn Gilbert’s writing course for behavior analysts at the University of North Texas. Her approach transformed my writing and that of other students. She was a behavior analyst “by marriage,” as well as a technical writer and instructional designer. She lamented that behavior analysts do not communicate effectively within their own community and beyond. In her course, students called Marilyn once a week to read aloud their essays to her. She would stop them after each sentence to give feedback. Once the course ended, I stayed in touch with Marilyn and she continued to guide me on how to improve my writing so that it would have a bigger impact.

I also spent a few years at the Mechner Foundation, working with Francis Mechner. He is a fantastic writer who takes a broad perspective and integrates the sciences, math, art, and philosophy into everything he writes related to behavioral science. He and Karyn Slutsky (his spouse), took the time to critique my writing line by line, and they gave me writing exercises and examples of well-written articles. Karyn is a professional editor who applied that skill to running the school she and Francis founded. She continues to shape my writing and demonstrate advanced techniques for improving mechanics, clarity of expression, and impact.

I’ve read books on writing, the media, and science communications from which I’ve gleaned a few “tricks” for writing effectively. One book I truly value is Living Proof: Telling Your Story to Make a Difference. It’s a step-by-step guide to writing advocacy stories that can be used to influence policy and communities. I have also taken courses in manuscript editing and grammar through University of Chicago, and these helped me learn about the publication and editing process.

All of this experience paid off when Adam went to work in the field, where he had to collaborate with such diverse professionals as classical musicians, music educators, talent development professionals, elementary school educators, and speech pathologists. “Through this work,” Adam says, “I learned to introduce and explain behavioral ideas while still honoring the framework of the situation. This enabled me to reach a wider audience.”

The Wider Reach Process

Adam orchestrates workshops at conferences and for organizations, such as universities, service organizations, ABAI affiliates, research collectives, and professional associations.

One of our workshop formats focuses on helping individuals write a piece for a mainstream publication. Prior to the workshop, they complete pre-work to identify what they’d like to write about; this helps me select a potential publication outlet. During the on-site or virtual workshop, participants learn about the mainstream publication process and how to structure their ideas in ways outlets will accept. Over two days, participants practice different strategies, and by the end most have completed a detailed outline or first draft. From then on, the Wider Reach team works with participants remotely to edit their pieces and draft pitch letters to the editors of targeted publications. We walk each participant through every step of the process, including how to communicate with publishers and handle rejections.

[I can’t say enough about Adam’s emphasis on communicating with editors and publishers. A lot of mainstream publications use systems very different from the peer-review drill of scholarly journals. Suffice it to say that if you don’t understand how articles are chosen for publication, yours has little chance of being chosen.]

Our other workshop format is for organizations. We help them create a strategic communication plan and identify people who can write the content. For example, we have hosted two virtual workshops for the executive leadership of an international affiliate to devise a communication strategy that aligns with their goals and barriers. We brainstormed their core messages and ways for them to reach their audiences. We also developed a list of prioritized pieces to write, along with potential publications for them, and we assigned the pieces to those in their community who are best suited to write them. At the next workshop, we will guide those writers through the steps of producing their pieces.

So far events have been held or scheduled at Georgia Southern University, Western Michigan University, University of Kansas/Juniper Gardens, Endicott College, West Virginia University, University of Nebraska Medical Center, and Rollins College.

Catching Fish

Graduates of Wider Reach workshops have developed articles on such diverse topics as yoga, police training, workplace safety, cultural and linguistic diversity, and online gaming harassment, to mention just a few. Here’s one of the success stories Adam shared with me:

Erin Houghton, a behavior analyst and special educator at Celeration Learning LLC in Maine, attended a Wider Reach workshop at the 2023 Precision Teaching conference. She owns a private practice that tutors students on academic skills. She wanted to write for educators, specifically, about a client who learned to effectively brainstorm before writing a paragraph or essay. During the workshop, Erin drafted a multi-paragraph outline (using techniques developed by Judith Hochman and Natalie Wexler). After the workshop, we worked with Erin to tighten up her outline, complete her first draft, and send a pitch letter to the editor of Edutopia. On March. 5, Erin’s article (“Guiding students in special education to generate ideas for writing“) was published and when I last checked it had attracted 604 reads on the Edutopia site, 79 Facebook shares, and 113 reactions.

Adam reports that 10 articles developed in Wider Reach workshops are currently in the publication pipeline, and he expects around 50 or so to have been submitted by the end of 2024.

Let me put those outcomes into context. Some years ago, ABAI hired a professional public relations firm, at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars, to grease the wheels toward more popular-press positive coverage of behavior analysis. The result was incredibly disappointing: not a lot of coverage, in not a lot of high-profile outlets. By contrast, the SABA grants are for a maximum of $5000. What Adam and Wider Reach are showing us, I believe, is that you can have a lot more success by showing behavior analysts how to disseminate their own stuff. An old saying about teaching a person to fish comes to mind here.

Find Out More

Wider Reach is addressing a long-standing hole in the technological expertise of behavior analysts: How to talk to PWANBAs. Meeting organisms where they are should not feel like a revolutionary concept, but that’s the adjective I’d apply to Wider Reach, because every single behavior analysts is a potential disseminator. Harness that, and we don’t need to wait around for the next Catherine Maurice to do our job for us.

For the moment, Wider Reach’s services are free of charge, though as Adam explains this could be temporary:

Generous funding from SABA will pay for the first 100 or so articles that get produced. I plan to pursue additional grants, especially those aimed at service organizations and affiliates. Wider Reach also accepts donations and is working to incorporate as a 501(c)(3). My hope is that affiliate chapters and other organizations will see value in the project and allocate a portion of their budget to host a writing workshop and/or cover editing services.

Check out the Wider Reach site and talk to Adam (widerreachincubator@gmail.com) about how your group can ride this new wave of active self-dissemination.

Postscripts

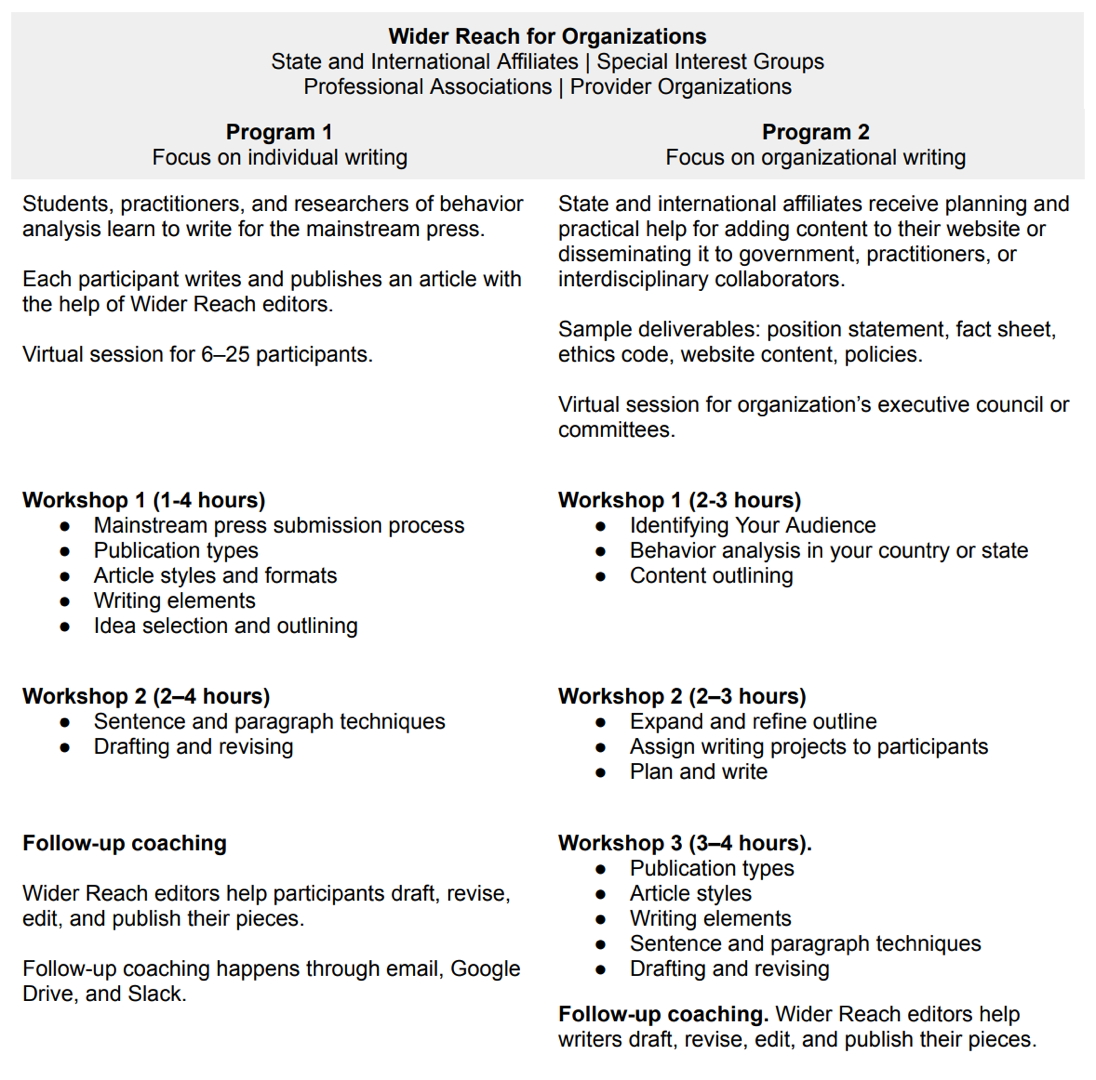

- To give you an idea about what’s covered in Wider Reach workshops, here’s a fact sheet for organizations (courtesy Wider Reach).

2. Rob Hawkins was a pioneer in school applications of learning theory. In fact, while on faculty at Western Michigan University, he established a journal called School Applications of Learning Theory (1970-1977), which later became Education and Treatment of Children. Rob moved on to West Virginia University, where he played a foundational role in the growth of WVU’s incredible behavioral child clinical Ph.D. program. A Google Scholar search will reveal that Rob was quite the applied-behavior-analyst-generalist, but one of my favorite threads in his work was a focus on dissemination via adapting behavioral interventions for implementation by consumers like parents and children. That emphasis, pleasantly enough, is entirely consistent with the spirit of Wider Reach.