Introduction by Blog Coordinator Darnell Lattal, Ph.D.

Dr. Green reminds us that our work is more than just the content of what we do; it is also the health and well-being of each of us doing the work. He recommends including physical well-being as part of our everyday practices and encouraging our clients to do the same. Based on years of practice and the applications research about making health a priority, he recommends we involve not only the employee but the leadership from top to bottom in ensuring this self-care is an important part of the culture of the organization. Nick provides a list of tips we can implement with ourselves and others inside organizations. Dr. Green, your name alone inspires visions of renewal, as in ever-green — as does your life work.

Who is Responsible for Employee Self-Care?

Nicholas Green, PhD, BCBA

We work. We engage in leisure activities. Not only that, but we work some more. And, if we are lucky, have the power to change our work and home environments to better promote our sense of well-being.

Enter self-care.

Self-care is a hot topic, with trends spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic and often during the new year — resolution, anyone? A Google trend analysis reveals such patterns:

(Google Trends Data, January 2024)

The nursing field teaches that self-care is “a multidimensional, multifaceted process of purposeful engagement in strategies that promote healthy functioning and enhance well-being (Dorociak, 2017).”

However, self-care hinges on an understanding and a relationship.

The employee provides value to the employer’s outputs and is compensated accordingly. Among the variables that contribute to an employee’s productivity, a hidden one remains in plain sight: employee health.

For us to our best work, who is responsible for our health? The employee, employer, or both?

A few historical points.

Work conditions were not ideal in the first 200 years of organized labor, but we course-corrected. Following the Industrial Revolution, laws prevented child labor and required industry to improve worker conditions — no more exposed saw blades, electrical hazards, or slippery floors. Employers gave workers a few days off (i.e., the weekend) and learned that this led to increases in work productivity during our standardized work week — Monday through Friday. Given these simple environmental changes, industry-produced goods — Model-Ts, church benches, and fountain pens — at profitable rates.

With this foundation, we see how our modern work evolved today. Knowledge workers are bound to the traditional Monday through Friday work schedule and are expected to work the industrialized standard of 40 hours per week. However, there is a catch, our job tasks require significant mental effort and do not require physical labor outside the Human Resources job requirement labeled, “you may be required to lift 20 pounds (9.07 kg)”.

For what? Carrying boxes of marketing material to the next campus recruiting event?

Whose Responsibility?

Outside of silly physical requirements — none of which are thoroughly assessed or monitored — both our physical and mental health will likely function as a major variable contributing to knowledge worker productivity. As a clinically trained behavior analyst, I value, present on, and follow this core principle, Benefit Others:

“Behavior analysts work to maximize benefits and do no harm by: Actively identifying and addressing the potential negative impacts of their physical and mental (italics emphasized) health on their professional activities (BACB, 2020)”

Although a part of behavior analysts’ code, this could be easily applied to other industries. Given this code, the question becomes, when an employee and employer enter a working relationship, where does the responsibility of addressing negative impacts lie?

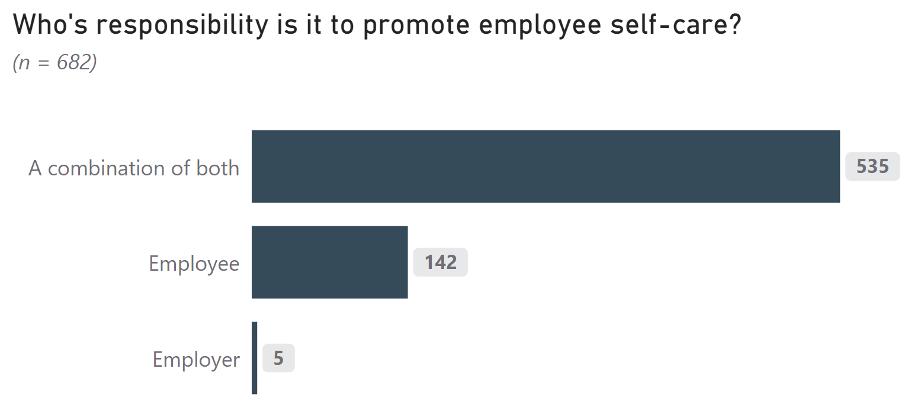

I delivered a live webinar on this topic regarding self-care and worksite wellness in January 2024 and asked this same question to a group of behavioral health clinicians. Here are the results:

The people have spoken — 78% of this subset of knowledge workers report that they believe the employer and employee should work together to support the employees’ wellbeing. How to get there is a separate challenge, but I am encouraged that working together should be a part of the solution.

Beyond that poll question, self-care in the workplace is a win-win for both employee and employer. As Slowiak and Delongchamp (2022) point out, self-care can be separated into personal and professional self-care. That is, behaviors and results that align with both values related to personal well-being (e.g., getting healthier) and workplace interests (e.g., advocating for career opportunities).

We can all agree that we all want to be a little healthier, a little less stressed, and more productive in all areas of our lives. By leveraging behavioral science, we can arrange our home and workplace environments to create positive conditions for promoting our self-care.

Guest Author: Nick Green

Nick Green, Ph.D., BCBA, spearheads BehaviorFit, dedicated to improving health and fitness with Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). Established in 2015 as a blog, BehaviorFit now offers advanced coursework, coaching, and consulting services.

With graduation training from the Florida Institute of Technology and the University of Florida, Nick combines behavioral psychology expertise with organizational behavior management and health behavior change. His career spans clinical work, organizational improvement, project management, product development, data analytics, and dashboard design.

As CEO, Nick ensures BehaviorFit’s evidence-based recommendations are personalized to each individual. Beyond work, he enjoys training his dog, Pete, and pursuing interests in productivity, photography, and Olympic weightlifting. Nick’s passion for sports like running, wrestling, golf, and baseball mirrors his dedication to physical activity and personal growth. Through BehaviorFit, he empowers individuals to achieve fitness goals, one behavior at a time.

Follow him on LinkedIn

References:

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts.

https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-code-for-behavior-analysts/

Dorociak, K. E., Rupert, P. A., Bryant, F. B., & Zahniser, E. (2017). Development of a self-care assessment for psychologists. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(3), 325.

Google Trends (n.d.). “Self care”, Retrieved on February 5th, 2024, from https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&geo=US&q=self%20care&hl=en

Slowiak, J. M., & DeLongchamp, A. C. (2022). Self-care strategies and job-crafting practices among behavior analysts: Do they predict perceptions of work–life balance, work engagement, and burnout? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(2), 414-432.