If you’re reading this, most likely you’ve chosen behavior analysis to anchor your professional identity and world view. In this post I’ll ask you to think critically about that choice. At the end, I’ll invite you to publicly defend your choice by entering a cool contest with a great prize. But first I need to explain the problem I’d like you to try to solve. Strap in.

Disclaimer: This post is A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT, an EXERCISE IN DEVIL’S ADVOCACY, THAT expresseS VIEWS WHICH ARE THE AUTHOR’S ALONE AND do not represent the position of contest sponsors, the Association for Behavior Analysis International, OR ANY OTHER MEMBER OF THE ABAI BLOG TEAM.

Woven deeply into the fabric of the culture that calls itself behavior analysis is the assumption, nay, bold confidence that our science is BETTER. Our swagger is evident in the separatist path we have chosen. Dissatisfied with the scientific methods and terminology employed by others, we invented our own. Dissatisfied with the professional conferences and journals that others created, we withdrew from those and formed our own. Dissatisfied with the quality of human services delivered by others, we established our own professional credential that only behavior analysts can hold.

We have a sense that we have cracked the code of behavior science, and with our science we, and only we, have the power to save the world. Skinner said it, not me:

No other field of science has ever been more clearly defined…or has a greater potential for solving the problems that face the world today.

Admit it: We think Behavior Analysis is BETTER.

Here I’m posing this question: Where is the proof?

A Hypothesis and Some Data

Behavior Analysis is BETTER is a hypothesis, and hypotheses are meant to be evaluated. One approach is to consider whether your hypothesis uniquely accounts for observations. If some alternative hypothesis can account for the same observations, then yours becomes less persuasive.

Here are some observations that need to be explained.

- We behavior analysts observe scientific rituals that virtually nobody else does. For instance, in research and practice, we insist on the individual as the unit of analysis, an approach that mystifies those who are accustomed to experimenting with groups. [Example of the frosty reception: For over 20 years a developmental psychology colleague badgered me, insisting that nothing learned from small-N designs has merit because a small N is synonymous with poor external validity; the badgering stopped only when he retired and moved away.] In theorizing, we insist on a particular way of speaking that few people understand. Richard Foxx has spoken eloquently about how this makes us look obtuse, or even nuts, and hinders the dissemination of our science.

- Collectively, these practices drive a wedge between us and the professionals and lay people who we think could profit from our science.

- We rigorously enforce each others’ adherence to our peculiar practices. For instance, in peer review we reject papers for scientific “sins” like studying groups rather than individuals or someone’s verbal reports rather than their physical actions. In conversation, we call each other out for linguistic sacrilege like saying “reinforce the organism” instead of “reinforce the behavior.” And we are suspicious of colleagues who mingle with outsiders. A while back some behavior analysts published a critique of a paper I co-authored. One feature of the paper that the critics said gave them pause was that it was not published in a behavior analysis journal. A similar theme: For a number of years I was fortunate, as a member of the Board of Directors of the Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis, to be part of deliberations to choose recipients of SABA Awards. On multiple occasions, I heard colleagues discount some otherwise worthy candidate on the grounds that they mostly published in mainstream journals and presented at mainstream conferences.

According to the Behavior Analysis is BETTER hypothesis, these are mundane facts. It seems obvious that our scientific practices are atypical because we are so far ahead of other sciences with interests in behavior. Our practices may cost us, in the currency of acceptance, but this is simply because outsiders are too steeped in a mentalistic culture to understand the superiority of our ways. We lean so hard on one another and keep to ourselves because, if we didn’t, societal countercontrol would undermine our science. Again, Skinner said it, not me. In his final article, “A world of our own,” he wrote that remaining apart might be the only way to nurture a truly great science of behavior.

Devil’s Advocacy: An Alternative Hypothesis

I will grant that behavior analysts are different, and apart. But that’s not necessarily synonymous with BETTER. When I was in graduate school, a woman with obvious mental illness lived for a time in a back stairwell of the university library. You could find her nearly any time of day or night in her “nest” of sleeping bag, old clothing, and vending machine snack wrappers, animatedly mumbling unrecognizable words to herself. She seemed scary, and any poor student unfortunate enough to wander into her realm would blanch and beat a hasty retreat. This woman was different and apart, but I don’t think she was thriving.

At the risk of sounding flippant, I’ll say that this anecdote may capture more of our situation than you might imagine. As Berger (1973) observed about us:

A devotee of Skinner can carry on conversation for hours and… the only recognizable symbols will be an occasional conjunction.

When the behaviorists gather and begin to discuss conjunctive schedules and respondent extinction, the social workers turn pale and begin to leave the room.

Could a different hypothesis, other than Behavior Analysis is BETTER, account for the ways in which we are different? To lob my devil’s advocacy grenade requires a bit of explanation, so please bear with me. My alternative hypothesis draws on costly signaling theory, which anthropologists invoke to explain the cultural practices of groups that are different and apart. Potz (2023) explained the theory thusly:

Adapted from evolutionary biology, this theory proposes that, by engaging in risky, burdensome, or otherwise costly behavior, individuals signal their commitment to the group, which, in turn, allows the group to eliminate free riders, enhances mutual trust, and facilitates effective cooperation… Costly signals are hard-to-fake signs of commitment beyond the simple profession of faith, such as engaging in time-consuming rituals, celibacy, behavioral restrictions, etc.

Costly signals are group-specific behaviors that outsiders find weird or objectionable. Sosis (2004) has noted that these behaviors seem, to a casual observer, to be nonsensical or even harmful:

I was 15 years old the first time I went to Jerusalem’s Old City and visited the 2,000 year-old remains of the Second Temple, known as the Western Wall. It may have foreshadowed my future life as an anthropologist, but on my first glimpse of the ancient stones I was more taken by the people standing at the foot of the structure than by the wall itself. Women stood in the open sun, facing the Wall in solemn worship, wearing long-sleeved shirts, head coverings and heavy skirts that scraped the ground. Men in their thick beards, long black coats and fur hats also seemed oblivious to the summer heat as they swayed fervently and sang praises to God. I turned to a friend, “Why would anyone in their right mind dress for a New England winter only to spend the afternoon praying in the desert heat?” At the time I thought there was no rational explanation and decided that my fellow religious brethren might well be mad.

The Orthodox Jewish practitioner seems to suffer directly from engaging in these rituals, but also indirectly, because, as Young Sosis observed, outsiders like Christians and Muslims and non-orthodox Jews are likely to judge the practitioner as daft, perhaps even threatening. The expected result is ostracism or worse.

However, costly signaling theory holds that the behaviors in question exist because they’re weird (non-normative), not despite that fact. Their weirdness fuels several behavioral functions that help to maintain group cohesion, but I’ll boil this down to two premises grounded in social cost (i.e., the fact that these in-group behaviors make outsiders uncomfortable). First of all, because they are costly, these behaviors signal to members of an in-group the individual’s genuine commitment to it. In essence, they convey that reinforcers gained from the in-group outweigh those lost outside the group. This establishes in-group trust, potentially increasing the frequency and magnitude of in-group reinforcers. Second, because outsiders tend to reject those they regard as weird, these behaviors create a no-turning-back scenario. Once you display one group’s costly signals, the odds of another group wanting you go down, and the in-group becomes the only reliable source of reinforcers. These two factors combine to create rock-solid in-group allegiance.

By the way, consistent with the tenets of the cultural materialism branch of cultural anthropology, the claim is not that someone intentionally designed costly signals with group cohesion as a goal, merely that groups which, for whatever reason, engage in costly signals are the ones most likely to endure.

Some of the evidence behind costly signaling theory is anecdotal, like this observation from Sosa (2004):

One prediction … is that groups that impose the greatest demands on their members will elicit the highest levels of devotion and commitment….This may explain a paradox in the religious marketplace: Churches that require the most of their adherents are experiencing rapid rates of growth. For example, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses, who respectively abstain from caffeine, meat and blood transfusions (among other things), have been growing at exceptional rates. In contrast, liberal Protestant denominations such as the Episcopalians, Methodists and Presbyterians have been steadily losing members.

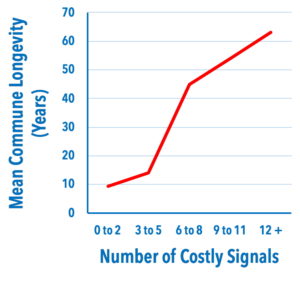

There is also research evidence. Sosa (2004) described a study in which he measured the longevity of 19th-Century religious communes. Then he combed their records to quantify how many prominent costly signals (weird behaviors) were dictated by each group’s culture. I’ve redrawn the findings to show that there was a clear pattern: The more costly signals in a group’s collective repertoire, the longer the commune held together.

It’s fascinating that many tests of costly signaling theory focus on religious groups, because the nominal benefits of religious practice, which concern one’s spiritual fate, are a matter of faith rather than objective evidence. Unless you’ve invented a digital “soul meter,” there is no objective basis for saying that one religion’s practices are better than any other’s at saving souls. Different religions just approach this mission in colorfully different ways.

Could costly signals also explain contrasting approaches to science — for which objective evidence of effectiveness seems possible? Consider the psychotherapy “theory war” of the 20th Century. Considerable effort was invested in debating the relative merits of various systems of therapy, each of which demanded colorfully distinct practices of their devotees. In the end, however, effectiveness research revealed the single biggest predictor of clinical outcomes to be not the particular brand of therapy but rather the quality of the therapeutic relationship, that is, the interpersonal connection between therapist and client. This finding raises the possibility that much of what makes the historically dominant systems of psychotherapy different is just costly signals that help to keep people devoted to the various systems.

What matters most in this example is that evidence, not faith, ended up anchoring the discussion. Could we apply the same standard to our own discipline?

So Is Behavior Analysis BETTER?

I’m finally getting to my devil’s advocacy point: What if the “weird” practices that make behavior analysis unique are simply costly signals? What if everything we do differently that we say makes us BETTER has evolved simply as a way of maintaining group cohesion?

This could be true without us realizing it — after all, no Jew at the Wailing Wall says to himself, “If I do this, I am helping to hold Orthodox Judaism together!” As Marvin Harris explained in his delightful book Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture, there is usually a “cover story” that group members tell, to themselves and outsiders to explain their cultural practices… but that story doesn’t necessarily correlate with real behavioral functions. We may tell each other, “We do this because it’s BETTER,” but doesn’t make it so. Just as, in the immortal words of Baer, Wolf, and Risley, “there is little… value in the demonstration that an impotent man can be made to say that he no longer is impotent,” normally there is little value in asking an in-group member why they emit the group’s customary, peculiar behaviors.

And yet now I’m asking you to do just that. The contest to be introduced below asks you to, in effect, refute my costly signaling hypothesis by providing objective evidence that behavior analysis really is BETTER.

Why This is Hard

To argue that Behavior Analysis is BETTER, in an objective sense, you need three things. First, you need a source of evidence about disciplinary success, the existence of which is subject to interobserver agreement. Second, you need a “control condition.” In keeping with the principle of constancy in science, this presumably means a case where some out-group took up the same problems we have, with equal gusto, but using a different approach. Third, the evidence must show that behavior analysis was more successful than the comparison group.

With these requirements in mind, let’s examine some common arguments that, in my opinion at least, are not persuasive.

- The philosophy of science fallacy. This type of argument focuses on the logical superiority of our approach. For instance, when first studying measurement, we’re told that hypothetical constructs, like those which are the focus of measurement in much of the rest of Psychology, are at best metaphors and at worst pure fiction. “Memory” and “personality” and the “self” are not real things — but behavior is! Focusing on constructs supposedly clouds our perspective on Nature’s laws, and focusing on real things supposedly makes us BETTER. But this is not objective evidence; it’s a premise, a rationale for one of the practices that makes us weird. We’re told that if we emphasize behavior over hypothetical constructs in measurement, better science and practice will follow. But that’s the hypothesis that bears testing, not evidence.

- Chicken Little (“The sky is falling!”) logic. This type of argument focuses on the devastating consequences of not doing science or practice our way. For example, we’re frequently told to use single-case experimental designs because group-comparison designs are so much worse. If you believe your textbooks, aggregating data from multiple individuals will yield false conclusions in the form of average outcomes that represent no individual. Consequently, we’re assured, single-case research yields better data, better theory, better practical applications. But go back to your textbooks and check for the evidence of those illusory functions that group data are said to show us. Almost always, you’ll find that the harm resulting from group-comparison designs is presented through hypothetical scenarios. This is not evidence, but merely speculation about what could go wrong in group research. Whether it really does apparently remains to be systematically established.

Side comment: In point of fact, it is hard to come up with very many examples where single-case and group-comparison researchers studied the same topic with equal gusto and arrived at different conclusions. Instead, single-case researchers in behavior analysis and group-design researchers in other disciplines usually study different things, making direct comparison difficult. Ah, but what you can find, ironically enough, buried in our own literature, are hints that the two approaches to design, when targeting the same questions, tend to arrive at the same truths. For instance, much of the foundational basic science on stimulus generalization employed group designs. Check it out for yourself. Pull up some studies from the 1950s through 1970s and you’ll see that a lot of what today we hold as axiomatic about generalization by individuals actually originates in that deadly sin, averaging data from multiple individuals (gasp). It’s hard to find much in the generalization literature that arose from early group research but was later overturned by single-case investigations.

- “Heuristic value” validation. This argument treats our success in addressing selected problems as evidence that other approaches were incapable of creating the same results. A classic case in point is autism, for which applied behavior analysis (ABA) has become the recognized treatment of choice. To take this as evidence of superiority assumes both that it was inevitable that behavior analysts would hone in and have success with on autism, and that other groups either would not or could not. But take a careful look at ABA’s history, and you’ll see that a focus on autism was shaped partly by happenstance. Behavior analysts did, from very early on, work with people with intellectual disabilities. But they did so partly because nobody else wanted that gig, and partly because they weren’t exactly invited in elsewhere. So ABA’s founders dug in and developed their craft where they could. To accentuate this point, imagine if, circa 1965, every school district in the United States had wanted to hire (at a fat salary) a behavioral instructional designer who would have real authority to change how children are taught. Do you think ABA would have evolved into Autism Incorporated? Or would it look different today?

Side comment: It’s not as if the first applied behavior analysts were prescient about intellectual disabilities and other thorny problems. I love Ted Ayllon’s admission, in Alexandra Rutherford’s history of ABA, Beyond the box, that when he first started working with residents in mental hospitals he didn’t believe behavioral procedures would work at all given how intractable those patients seemed. Progress since then has been gradual and uneven; for instance, it took more than thirty years after the birth of ABA for that bedrock procedure, the functional behavioral assessment, to become formalized. And let’s acknowledge that there have been false starts in the evolution of behavioral treatments. No behavior analyst of my generation can forget a horrific early film in which Ivar Lovaas repeatedly screams at and slaps children in the name of “treatment.” At that time applied behavior analysts were very much still figuring out, by trial and error, what worked and didn’t. [And, heck, we’re still figuring that out. Consider the controversial use of contingent electric shock, which today continues to divide our discipline and bring scorn upon it.] All I’m saying is that it’s a mistake to confuse ABA’s autism success with destiny. The success is awesome, but circa 1960 it was by no means inevitable, based on characteristics of the underlying science, that ABA would become today’s preferred form of autism treatment.

Side comment: It’s not as if the first applied behavior analysts were prescient about intellectual disabilities and other thorny problems. I love Ted Ayllon’s admission, in Alexandra Rutherford’s history of ABA, Beyond the box, that when he first started working with residents in mental hospitals he didn’t believe behavioral procedures would work at all given how intractable those patients seemed. Progress since then has been gradual and uneven; for instance, it took more than thirty years after the birth of ABA for that bedrock procedure, the functional behavioral assessment, to become formalized. And let’s acknowledge that there have been false starts in the evolution of behavioral treatments. No behavior analyst of my generation can forget a horrific early film in which Ivar Lovaas repeatedly screams at and slaps children in the name of “treatment.” At that time applied behavior analysts were very much still figuring out, by trial and error, what worked and didn’t. [And, heck, we’re still figuring that out. Consider the controversial use of contingent electric shock, which today continues to divide our discipline and bring scorn upon it.] All I’m saying is that it’s a mistake to confuse ABA’s autism success with destiny. The success is awesome, but circa 1960 it was by no means inevitable, based on characteristics of the underlying science, that ABA would become today’s preferred form of autism treatment.

-

The “But we have data!” boast. This argument focuses on world-changing potential via our mountain of single-case data supporting the claim that ABA is effective. But the relevant studies almost always compare treatment to a no-treatment baseline, a strategy that can only reveal whether treatment is better than doing nothing. To claim that ABA is BETTER requires comparing it with another form of treatment, and the scholarly consensus is that this requires large-N randomized controlled trials (those are group-comparison designs, folks!) that are evaluated using statistical techniques. I can’t resist the observation that in order to show that our stuff is BETTER could require using scientific methods that many behavior analysts reject. But setting aside that conundrum, it’s important to recognize that a growing number of large-N studies are converging on the conclusion that the available evidence supports ABA’s effectiveness but not its superiority. For examples see here and here and here and here. If you’re inclined to see something sinister in the fact that most of these reports originate outside of the behavior analysis literature, by all means check out this newly published paper in Perspectives on Behavior Science.

A Contest!

I don’t believe in prizes for adults or for children.

– B.F. Skinner, quoted by Holth (2018)

I do. They’re fun.

– Tom Critchfield

So there you have it: My effort to apply critical thinking to the proposition Behavior Analysis is BETTER.

To be clear about my motivation, I see nothing wrong with trying to be BETTER. Indeed, I hope we all agree that this is the goal and that we have an ethical duty to try to achieve it.

But I hope we can agree as well that premature “Mission Accomplished!” pronouncements are damaging to the cause. No reason to try harder if you’re already #1, right? So let’s take a careful look at where we stand. If the evidence supports our collective swagger, great! If not, let’s find out why and begin to discuss how to do better. The first step is an all-important look in the mirror.