In this month’s ABAI Symbolic Language and Thought blog we have insights from Dr. Colin Harte and Prof. Dermot Barnes-Holmes on the verbal sense of self and consciousness. This one is a fun intellectual workout so get the popcorn out and enjoy!

Thank you Colin and Dermot for joining the ABAI Symbolic Language and Thought Blog series. -Prof. Louise McHugh, University College Dublin, ABAI Symbolic Language and Thought Blog series host.

Colin Harte Bio: Colin received his PhD in 2020 under the supervision of Professors Dermot and Yvonne Barnes-Holmes at Ghent University in Belgium. His doctoral work was part of the Odysseus research project which focused on the conceptual development of relational frame theory (RFT) as a behaviour analytic account of human language and cognition. His work during this time focused on exploring the behavioural dynamics involved in rule-governed behaviour, and persistent rule-following specifically. Since then, Colin has continued to be heavily involved in the empirical and conceptual development of RFT more  generally. To this end, he has published 18 peer reviewed journal articles, 2 book chapters in edited volumes and presented multiple papers and workshops at international behaviour science conferences. He is currently an associate faculty lecturer in psychology at the National College of Ireland (NCI) in Dublin and has recently been awarded a post-doctoral research fellowship by the São Paulo research foundation (FAPESP) with Professor Julio de Rose which he intends to take up once it’s safe to travel again.

generally. To this end, he has published 18 peer reviewed journal articles, 2 book chapters in edited volumes and presented multiple papers and workshops at international behaviour science conferences. He is currently an associate faculty lecturer in psychology at the National College of Ireland (NCI) in Dublin and has recently been awarded a post-doctoral research fellowship by the São Paulo research foundation (FAPESP) with Professor Julio de Rose which he intends to take up once it’s safe to travel again.

Bio: Prof. Dermot Barnes-Holmes received his D.Phil. in behavioral analysis and behavioral biology from the University of Ulster, Coleraine, N. Ireland. He returned to Ulster University in 2020 to take up a professorial position in the School of Psychology. Previously, he served as Senior Full Professor and Odysseus Laureate at Ghent University, Belgium, having previously served on the faculties of the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, and University College Cork. Dr. Barnes-Holmes is an extraordinarily prolific researcher who has made extensive contributions to the behavior analytic literature, especially in the areas of language and cognition. The competitive and prestigious Odysseus Laureate awarded to Dr. Barnes-Holmes in 2015 is just the most recent recognition of the esteem in which his work is held among behavioral scientists internationally.

the behavior analytic literature, especially in the areas of language and cognition. The competitive and prestigious Odysseus Laureate awarded to Dr. Barnes-Holmes in 2015 is just the most recent recognition of the esteem in which his work is held among behavioral scientists internationally.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes, et al., 1999) emerged from clinical behavior analysis and was tied closely to the behavior-analytic account of human language and cognition known as relational frame theory (RFT; Hayes, et al., 2001). Many of the concepts in ACT are defined as middle-level terms, such as “self-as-context” and “defusion,” and are difficult to connect directly to traditional behavior-analytic concepts. Indeed, such middle-level terms, it has been argued, are even difficult to connect directly to RFT (Barnes-Holmes et al., 2016). In a recent chapter, referenced below, we presented an overview of RFT, which drew on recent empirical and conceptual developments in the theory itself. In doing so, we did not offer an RFT “point-to-point translation” of middle-level concepts in the ACT literature. Indeed, such direct translation should not be expected because a primary purpose of basic or technical analyses is to generate verbal stimuli that control scientific behaviors (among basic and applied researchers, and practitioners) in new and unique ways; direct translation, by definition, cannot achieve this aim because one term is simply replaced with another and no substantive change in scientific or therapeutic behavior is required or encouraged.

In keeping with this general approach for the current blog, we will refrain from providing current definitions of specific middle-level terms or focusing on particular therapeutic interventions or exercises. Instead, our objective is to show how recent developments in the empirical and conceptual development of RFT may permit an increasingly technical account of the verbal self. Thus, we will build our account from the “bottom up” and allow readers, who have some knowledge of ACT, to judge if the technical analyses we offer are perhaps relevant to one or more ACT-based middle-level concepts that refer to self, such as self-as-context and indeed other middle-level terms such as defusion.

Deictic Relations and the Verbal Self

A considerable body of conceptual and empirical research has been conducted on deictic relational responding in RFT, which is seen to be critical for the emergence of a verbal self. For RFT, three core relations are involved in deictic relating (Barnes-Holmes, 2001): the interpersonal relation, I-You, the spatial relation, Here-There, and temporal relation, Now-Then. These three types of relations combine into the basic or simplest deictic relational frame, which involves locating oneself in time and space relative to another individual. The core idea is that as children learn to respond in accordance with these deictic relations, they are essentially learning to relate the self to others in the context of particular times and spaces. For example, imagine a very young child being asked “What did you have for breakfast at home this morning?” while they are eating lunch in a restaurant later that day with their family. If the child responds simply by referring to what, for example, their sister is currently eating, they may be corrected and told “No, that’s what your sister is now eating here. What did you eat earlier at home for breakfast?” Ongoing refinement of the three deictic relations in this way thus allows the child to respond appropriately to questions about their own behaviour in relation to others, as it occurs in specific times and places (e.g., McHugh et al., 2004).

The concept of deictic relations highlights that a verbal human’s sense of self is, in a sense, socially constructed. The construction of this self begins with the cooperative acts involved in what has been termed mutually entailed orienting and evoking (see Harte & Barnes-Holmes, in press; Barnes-Holmes & Silvarman, 2020, for a detailed exposition). In brief, when a care-giver orients an infant towards a toy teddy bear, for example, and asks the child do you want the teddy, the child may reach towards the bear as part of that cooperative act, without yet understanding a word that the care-giver has uttered. Nevertheless, the overarching evolutionary history of human cooperation involved in child-rearing has begun to establish the verbal self from which all events will be viewed. In this sense, the verbal self is another term for having a perspective, as experienced by a verbal human. In a technical RFT sense, therefore, it is not possible for a verbal human to experience the world non-verbally (at least in a pure sense of ‘non-verbal’), once a history of mutually entailed orienting/evoking has begun to establish arbitrary relations with I-You, Here-There, and Now-Then. Metaphorically speaking, the young child is being dragged verbally out of the garden of Eden with a gradual loss of ‘non-verbal’ innocence.

Deictic relational responding is viewed as being relatively advanced because it involves learning to respond to one’s own relational responding. As noted elsewhere (e.g., Harte & Barnes-Holmes, in press), this level of relational responding is likely involved in relating relations, and certainly in relating entire relational networks to other relational networks. In simple terms, a child would find it difficult to relate two separate relational responses if they could not “locate” those relational responses in a specific time and space. Indeed, this basic argument has been elaborated recently by Kavanagh et al. (2019) in their presentation of an RFT interpretation of the classic false belief perspective-taking task. We will not dwell on this work here, but the core technical RFT conceptual analysis will be employed and elaborated in dealing with the verbal self and altered states of consciousness. Before dealing with the verbal self specifically, we will first outline the general RFT (technical) analysis itself.

An RFT Technical Analysis of Human Psychological Events

A growing number of recent experimental and conceptual analyses in RFT have focused on a framework that proposes five key levels of relational development; (i) mutual entailing, (ii) relational framing, (iii) relational networking, (iv) relating relations, and (v) relating relational networks. These five levels of relational activity are seen as intersecting with four dimensions that target key variables that may be manipulated in exploring the dynamic nature of arbitrarily applicable relational responding (AARR; the generic concept used in RFT to define human language and cognition itself). The four dimensions are coherence, complexity, derivation, and flexibility. Coherence refers to the extent to which a pattern of derived relational responding coheres or is consistent with previously established patterns of such responding. Complexity refers to the level of detail or density of a particular pattern of derived relational responding. Derivation refers to the extent to which a particular pattern of derived relational responding has been “practiced” or emitted in the past. Flexibility refers to the extent to which a given instance of derived relational responding may be modified by contextual variables.

The intersections between the levels of relational development and the four dimensions yield 20 units of analysis, thus producing a hyper-dimensional multi-level (HDML) framework (see Figure 1). The Figure also illustrates a general concept that emerges from the framework, referred to as the ROE-M (pronounced “roam”), which provides a way of conceptualizing human psychological events as they unfold in real time (see Harte & Barnes-Holmes, in press, for a detailed treatment). Specifically, each cell of the HDML contains an inverted ‘T’ with a third dashed line. This symbol represents orienting and evoking functions, and the impact of motivating variables, that may occur within each of the 20 units of relating. Orienting refers to the extent to which a stimulating event is noticed or “stands out” in the wider context. Conceptually, orienting within the HDML is seen as lying on a continuum, on the vertical axis, from complete absence (0) to strongest orienting response possible (1). Evoking refers to the extent to which a stimulating event is deemed to be appetitive versus aversive. Evoking is also seen as lying on a continuum, on the horizontal axis, from the strongest aversive response possible (-1) to the strongest appetitive response possible (+1) with 0 representing the absence of either an aversive or appetitive reaction. Motivating is represented with the broken line, which is scaled from 0 to 1, indicating the putative strength of motivational variables, which interact with orienting and/or evoking functions, and indeed relating, in a dynamical manner (see below). The core or fundamental unit of analysis for AARR is thus defined as relating, orienting, and evoking within a given motivational context. The unit is summarized with the acronym, ROE-M.

As an aside, in RFT, all instances of relating are controlled by specific contextual cues (i.e., Crels) and the psychological functions that are actualized by such relating are controlled by other cues (i.e., Cfuncs). When we refer below to Crel properties this indicates the relational nature of an event (e.g., the word “apple” coordinates with an actual apple), whereas reference to Cfunc properties indicates the psychological reaction to the event (e.g., the word apple may evoke some of the appetitive properties of an actual apple).

Figure 1. A visual representation of the HDML

Note. 20 intersections between the five levels and four dimensions of the arbitrarily applicable relational responding, combined with orienting and evoking functions, and motivating variables. Note that motivating is represented by a broken line because its impact is inferred based on changes in orienting and evoking functions. Overall, this figure aims to capture the dynamic nature of AARR (i.e., relating, orienting, evoking, and motivating; the ROE-M).

The RFT analysis outlined above proposes that most if not all human psychological events (for verbal humans) involve the ROE-M. As an illustrative example, a mutually entailed relation (e.g., “Covid-19 is awful”) may be conceptualized as varying in coherence, complexity, derivation, and flexibility. In general terms, the relation between Covid-19 and awful may be relatively high in coherence if the statement coheres with similar assertions (e.g., “Covid-19 has killed over 2 million people worldwide”); relatively low in complexity if understanding the statement involves a limited number of other relational responses (e.g., the label “Covid-19” was applied directly to an “awful” event, such as the diagnosis and death of a loved one); relatively low in derivation (e.g., if similar statements have been heard many times in the past); and low in flexibility (e.g., if it is difficult to modify or “challenge” the perceived truth of the statement). Critically, this relational activity is seen to interact in a non-linear and dynamical manner with the orienting and evoking functions of stimulating events for humans as they navigate their environments. For example, a passing comment (“Isn’t Covid-19 awful?”) may increase orienting and (aversive) evoking functions for others’ sneezing and coughing while travelling on public transport. Various motivational variables will likely impact on the relative strengths of the orienting and evoking functions, such as personal health risk factors (e.g., age, weight, pre-existing medical conditions, etc).

It is important to emphasize the inseparable, interactive and non-linear nature of ROE-Ming that the HDML aims to capture. In the example provided above of someone passing a negative comment about Covid-19 (i.e., it is awful), the comment could increase orienting and evoking functions for sneezing on public transport. In contrast, imagine that no such comment was made. You may be less likely to orient as strongly and as aversively towards someone else sneezing, but may still engage in some level of relating, such as emitting a relational network that functions as a self-rule (e.g., “I better keep my distance in case that person has Covid-19”). And of course, the nature and relative strength of the relating and orienting/evoking will be moderated by motivational variables. In essence, the concept of the ROE-M is designed to capture the constant, dynamical, and non-linear nature of the core unit of responding that characterizes human psychological events. From an RFT perspective, the set of relational abilities, and associated orienting and evoking functions (interacting with motivational variables) contained within the ROE-M, appear to be core defining characteristics of the human species, which allow us to navigate and react to our physical and social environments in increasingly sophisticated and powerful ways.

Relating Relational Networks and the Verbal Self

A HDML analysis of the verbal self seemingly involves responding at the highest level of relational development (relating relational networks), which we will explain shortly. In order to get to this highly advanced level a number of critical relational precursors would need to be firmly established within the individual’s behavioral repertoire. First, a number of basic relational frames (e.g., coordination, distinction, containment, and temporality) would be required to be in place, therefore involving the first two levels of relational development as specified within the HDML framework (mutual entailment and relational framing). These basic patterns of relational responding would also need to be high in coherence (i.e., consistent with many other past and current instances of responding in accordance with these patterns), relatively high in complexity (i.e., subject to multiple sources of contextual control), low in derivation (i.e., have relatively extended histories), and low in flexibility (i.e., should persist in the absence of supporting contextual variables, such as reinforcement, and in contexts that could undermine such responding, such as “mild” punishment).

In addition to relatively basic relational frames, the three core deictic relations (I-You; Here-There; Now-Then) would also need to be firmly established, as a relational frame, within the individual’s repertoire. While the deictic frame could be seen as located at the second level of relational development, if well established it would likely also participate within larger relational networks (i.e., the third level of relational development specified by the HDML framework). Furthermore, as is the case for the frames of coordination, distinction, containment, and temporality the deictic frame would similarly need to be high in coherence and complexity, and low in levels of derivation and flexibility. Responding in accordance with these increasingly complex relational networks, at these dimensional levels, would likely be crucial in order for the individual to “locate” relevant relational responses in a specific time and space (e.g., “I thought about that yesterday before you got here”).

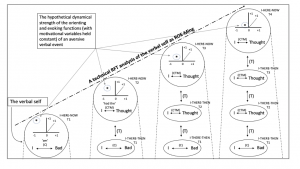

Assuming these relevant precursors are sufficiently established in the individual’s history, it is likely that a sophisticated or advanced example of the verbal self would involve relating entire relational networks to other entire relational networks. To appreciate the detailed analysis we will now provide, the reader should refer to Figure 2, and first examine the bottom, left-hand, corner of the figure. The circle contains a graphical representation of a HDML analysis of the relating, orienting, and evoking (with motivational variables held constant in the current example) of a verbal self “having a thought,” in this case, “I am bad.” (i.e., the “I” network is in a coordination relation with the “bad” network). In a sense, at T1, the verbal self is the relational response, “I am bad” including its various functions, and the contextual history that led to that response at that point in time. Parenthetically, readers familiar with ACT may begin to see some overlap between the example of the verbal self we present here and certain therapeutic exercises. As noted earlier, however, it is not our intention to present a technical analysis of any specific ACT exercise or intervention, but we have drawn on an ACT-relevant example given the historical connection between ACT and RFT. In principle, therefore, the thought “I am bad” could be substituted with any verbal relation or even a highly complex network (we will consider an example of the latter subsequently).

Figure 2. A technical RFT analysis of the verbal self as ROE-Ming

Note. ‘(C)’ refers to a coordination relation, ‘(T)’ to a temporal relation, and ‘(CTM)’ to a containment relation. The vertical axis for the inverted ‘T’ indicates the dimension of relative strength for orienting functions, the horizontal axis for evoking functions, and the dashed diagonal line motivational variables. The asterisk indicates the relative strength of the orienting and evoking functions of the “I-bad” coordination relation for each of the four ROE-Ming events, I-Here-Now T1-T4 (reading from left to right).

The hypothetical orienting and evoking properties of the “I-bad” relation are plotted as an asterisk on the inverted ‘T’, indicating strong orienting and highly aversive evoking responses. The inverted ‘T’ and the relational response (“I” coordinated with “bad”) are contained inside a single circle to indicate the “leading edge” of the analysis of the verbal self (I, Here, and Now). The two dashed lines extended from the circle indicate that the “verbal self” is conceptualized as a behavioral unit of analysis, in this case the ROE-M, that is continuously in flow, and as such subsequent behavioral events will always follow, at Time 2, Time 3, and so on.

Imagine now that the verbal self responds relationally to the verbal event that has just occurred (e.g., during a course of ACT), responding at Time 2 with “I just had the thought that I am bad.” The hypothetical relational activity involved is illustrated to the right of the first circle in Figure 2. Informally, the verbal self is having a thought about a thought, in this case “I had the thought that I am bad.” In technical terms, the phrase “had the” functions as a contextual cue which specifies the type of relation (i.e., a Crel), in this case containment rather than coordination (as in “I had the thought” versus “I am the thought”, respectively). Note that we use the term containment here because when combined with deictic relations, thoughts are usually responded to as things that occur inside the head or mind. In terms of the diagram, the containment relation (“I had the thought that”) is in a temporal relation with the coordination relation (“I am bad”). Technically, this may be interpreted as relating relational networks. Specifically, the “I am bad” network at Time 1 (I-There-Then) is related to the “I had the thought” network at Time 2 (I-Here-Now). The hypothetical orienting and evoking properties of the “I-bad” network may be seen as reducing slightly, as indicated by the shift down and towards the right of the asterisk inside the inverted T. The changes in the orienting and evoking functions may occur for a number of reasons. For example, the elaboration of a network involving coordination between “I-bad” to networks involving both coordination and containment (also involving a temporal relation), may begin to undermine the narrow and inflexible repertoire that is typically controlled by the “I-bad” network alone. In broad terms, the dominance of the Cfunc properties of the “I-bad” network are reduced as additional Crel properties elaborate the original network with a relatively non-aversive event (i.e., “neutral” thoughts I have, rather than a thought about who I am).

If we extend this example, imagine the verbal self responds relationally to the two verbal events that have just occurred. More informally, they continue to notice that they just had a thought that they are bad, and then they have a thought, that they had a thought that they are bad, thus moving over another step to the right in Figure 2. Technically, the “I am bad” network at Time 1 (I-There-Then) is related to the “I had the thought” network at Time 2 (I-There-Then) which is related to another “I had the thought” network at Time 3 (I-Here-Now). Once again, the reader is directed toward the position of the asterisk inside the inverted ‘T’, which indicates that the hypothetical orienting and evoking properties of the “I-bad” network may be seen again as reducing, as additional Crel properties further elaborate the original network. One more step in the example is illustrated when I-Here-Now occurs at Time 4 (i.e., the far right of Figure 2). More informally, the verbal self notices that they had a thought, about a thought (I-There-Then, Time 3), about a thought (I-There-Then, Time 2), that they are bad (I-There-Then, Time 1). Once again, technically, a reduction in the Cfunc properties of the “I-bad” network are represented by a further shift in position of the asterisk inside the inverted ‘T’ as yet additional Crel properties elaborate the original network. We remind the reader to observe the two dashed lines extended from each circle at each time-point, illustrating the continuous flow of the ROE-M as a behavioral unit of analysis (of the verbal self) unfolding in current and historical contexts.

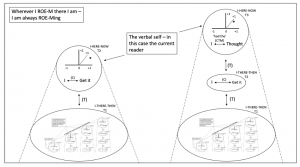

To appreciate the “reflexive nature” of the technical analysis being offered here it may be useful for the reader to briefly consider their own reaction to the analysis itself (see Barnes & Roche, 1997). Imagine, for example, that you (the reader) just had the thought “I get it” (or “This is weird, I just don’t get it”) about the analysis. This is represented in the left-hand side of Figure 3, in which that reaction (e.g. “I get it”) is represented as I-Here-Now at Time 2, as related to the entire technical analysis as I-There-Then at Time 1. Note that I-Here-Now at Time 1 is not shown in Figure 3 (i.e., the verbal self “working through” the technical analysis itself); this would be represented by placing the complex network analysis depicted in the bottom-left circle, inside the small circle above, thus replacing the “I get it” relation, which can only follow an attempt to understand the prior technical analysis. If we extend the reflexive event (see right-hand side of Figure 3), the reader then has the thought “I had the thought” (I-Here-Now at Time 3), about “I get it” (I-There-Then at Time 2), about the entire technical analysis (I-There-Then at Time 1). Note, that the position of the asterisk in the inverted ‘T’ indicates a generally positive evoking function because the reader “gets the analysis”; if the reaction was “This is weird, I just don’t get it”, then the position of the asterisk might indicate a less positive or even negative evoking function. In either case, the position of the asterisk would likely shift slightly closer to the zero point as the dominance of the Cfunc properties of the “I get it” network are reduced as the Crel properties elaborate the original network with a relatively neutral event (i.e., a “neutral” thought about a thought, rather than the appetitive thought itself). The point here is to appreciate that the verbal self as the ROE-M is never static but is constantly moving and unfolding in all current and historical contexts. To paraphrase a mindfulness-based quote by Jon Kabat-Zinn (1994), “Wherever I ROE-M, there I am”.

Figure 3. The reflexive nature of a technical RFT analysis of the verbal self as ROE-Ming

Note. See caption for Figure 2 and text for additional relevant details.

The Verbal Self and “Altered States of Consciousness”

Arguing that the verbal self, interpreted as the ROE-M, is never static should not be taken to mean that variations within and among the properties of the ROE-M cannot become severely reduced (i.e., to a quasi-static state). Indeed, allowing for reductions in variation to near-zero levels in and among the four dimensions of the HDML (coherence, complexity, derivation, and flexibility), and the Cfunc properties of orienting and evoking, with motivation held relatively constant, is critical in providing a technical analysis of at least some so-called altered states of consciousness. Consider, for example, the mystical or spiritual experience that was discussed by Hayes (1984), and others since then (e.g., Barnes & Roche, 1997).

Such experiences frequently involve reports of a loss of sense of self and also time and space. The boundaries between the self and reality appear to break down, such that the self experiences being “at one with the universe” or being “everywhere and nowhere at the same time.” As noted above, such experiences may involve a substantive and protracted reduction in variations in and among the dynamics of the properties of the ROE-M. For example, virtually all meditative practices involve removing potential sources of Crel and Cfunc “distractors” (e.g., focusing on breathing rather than external stimuli or staring at a candle flame and/or engaging in repeated chanting). In such cases, the properties of the ROE-M do not necessarily “disappear”, rather changes or variations in the variables greatly diminish. Thus, orienting, for example, may be seen as relatively high (e.g., by staring at a candle flame), but fluctuations in that orienting response will be minimal during a successful meditative exercise because one stares at the flame, without distraction, and nothing else. Similarly, the Cfunc property of evoking may be conceptualized as relatively appetitive (i.e., the meditative experience is generally considered to be positive) but with very little variation in the appetitive quality of the experience itself.

With the extensive and protracted reduction in variations in the Cfunc properties of orienting and evoking, the relating property of the ROE-M will gradually approach zero (because there is very little to relate about). That is, the extended and uninterrupted focus of the meditative experience (e.g., on the candle flame or the sound of the chant) gradually removes variations in the stimulus properties of the environment that typically provide the source for Creling itself. In this sense, relational responding to the flame or chant becomes neither coherent or incoherent, simple or complex, high or low in derivation, or flexible versus inflexible. We are not suggesting that the dimensions, per se, completely “disappear” but variations in and among those dimensions may approach zero during a successful meditative exercise, particularly one that generates an altered state of consciousness.

In terms of the verbal self, metaphorically speaking, the polarities in the three deictic relations (I-You, Here-There, Now-Then) may be seen as “collapsing” during the meditative event, such that the self is experienced as everyone and no-one, everywhere and nowhere, and without (temporal) beginning or end. Technically, the so-called collapsing in the polarities of the deictic relations remains a verbal event, in the sense that a verbal history is involved in generating that event. Furthermore, the event, as it occurs, maintains some verbal properties, in that these properties participate in entailed relational responding, as the meditative exercise comes to an end (e.g., when the meditative experience is labelled “weird,” “strange” “amazing” or “scary,” etc.). Epistemologically, within the world view of behavior analysis, even the “collapsing” in the polarities of the three deictic relations is intensely verbal because all psychological events are known, defined, and explained in terms of a current and historical behavioral context, not in terms of how an event feels when it is experienced.

Conclusion

The current blog has provided a conceptual RFT analysis of the verbal self in largely technical terms. In doing so it has drawn heavily on recent experimental analyses within RFT (see Harte & Barnes-Holmes, in press), recognizing that the Cfunc properties of orienting and evoking become related (in an arbitrarily applicable manner) to increasingly complex networks (as depicted in the HDML). The ROE-M thus emerges as a functional-analytic-abstractive unit of analysis. The ROE-M is a-topographical, in that it does not refer in any way to physical behavior, not even specific relational frames. Of course, specific relations, frames, and networks may be invoked in any given analysis within a domain of interest, but the core unit (the ROE-M) remains “frameless.” In the current case, that domain is the self, and the ROE-M appears to be useful in providing a technical RFT analysis of the verbal self, including self-related verbal events, such as thoughts about thoughts and so-called altered states of consciousness.

*Some of the material in the current blog appears in a chapter in the upcoming Oxford Handbook of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [Harte, C. & Barnes-Holmes, D. (In press). A primer on Relational Frame Theory (RFT). In M.P. Twohig, M.E. Levin, & J.M. Peterson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oxford University Press.]; copyright granted by the Oxford University Press under the fair use doctrine.

References

Barnes, D. & Roche, B. (1997). A behavior-analytic approach to behavioral reflexivity. The Psychological Record, 47, 543-572. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395246

Barnes-Holmes, Y. (2001). Analysing relational frames: Studying language and cognition in young children (Unpublished doctoral thesis). National University of Ireland Maynooth.

Barnes-Holmes, Y., Hussey, I., McEnteggart, C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Foody, M. (2016). Scientific ambition: The relationship between relational frame theory and middle-level terms in acceptance and commitment therapy. In R.D. Zettle, S.C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds.) The Wiley handbook of Contextual Behavioural Science (pp. 365-382). Wiley-Blackwell.

Barnes-Holmes, D. & Sivaraman, M. (2020, August 14). Updating RFT: cooperation came first, the ROE as a unit of analysis, and engineering prosocial behaviour. https://science.abainternational.org/up-dating-rft-cooperation-came-first-the-roe-as-a-unit-of-analysis-and-engineering-prosocial-behavior/louise-mchughucd-ie/

Harte, C. & Barnes-Holmes, D. (in press). A primer on Relational Frame Theory (RFT). In M.P. Twohig, M.E. Levin, & J.M. Peterson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oxford University Press.

Hayes, S.C. (1984). Making sense of spirituality. Behaviorism, 12(2), 99-110.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D, & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Plenum.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K.G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion

Kavanagh, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2019). The study of perspective taking: Contributions from mainstream psychology and behaviour analysis. The Psychological Record, 70, 581-604.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-019-00356-3

McHugh, L., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2004). Perspective-taking as relational responding: A developmental profile. The Psychological Record, 54, 115- 144. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395465