For the November ABAI Symbolic Language and Thought blog entry I am delighted to have my dear colleague and world leading RFT expert Dr. Fran Ruiz. Fran blogs about the verbal nature of human joy and suffering. At this time of global challenge the post provides evidence based ease from our ruminative thoughts that can entangle us and pull us away from what matters. – Prof. Louise McHugh, coordinator for the ABAI Symbolic Language and Thought blog series.

Bio: Francisco J. Ruiz received his doctoral degree in Psychology in Universidad de Almería (Spain) under the supervision of Dr. Carmen Luciano in 2009. He worked in several Spanish universities before accepting a professor position in Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz (Colombia) in 2015. In this position, he designed one of the first Ph.D. programs in Psychology in the country and has been awarded as a “Distinguished Researcher” of the institution. He has published about 75 scientific articles focused on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Relational Frame Theory (RFT). During the last few years, he and his colleagues are developing an ACT model that focuses on dismantling dysfunctional patterns of repetitive negative thinking (RNT). He is a Fellow of the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science and acts as Associate Editor of the Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science.

Why do human beings enjoy and suffer differently from other animal species? Where does this joy and suffering come from? Why do some human beings develop a meaningful life while others a life full of suffering? In this blog entry, I will try to briefly answer these questions based on the functional-analytic approach of human language and cognition known as Relational Frame Theory (RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001).

Human beings are born with a series of primary reinforcers that reflect the phylogenetic history of our species. Among these are positive reinforcers such as food, drink, physical contact, and negative reinforcers such as loud noise or violent physical contact. The contact with these reinforcers is associated with experiencing appetitive and aversive emotions.

Through respondent and operant conditioning, multiple neutral stimuli soon acquire the property of secondary reinforcers such as the mother’s voice while the baby is being fed or the father’s worried face that precedes the presence of screams. Some of these secondary reinforcers will probably become generalized reinforcers such as money, social approval, or criticism. In other words, the array of stimuli that will provoke emotional responses in the child will increase significantly.

The range of stimuli that will function as reinforcers will extend exponentially as the child develops skills in relational framing (or arbitrarily applicable relational responding). Relational framing means responding to one event in terms of another based on arbitrary relational cues. There are different patterns of relational framing, including coordination (“is,” “same as”), distinction (“is different from”), opposition (“is opposite to”), comparison (“more than,” “less than”), hierarchy (“is part of,” “includes”), deictic (I/here/now vs. you/there/then), causal (“if… then”), etcetera. Transformation of functions is the main property of relational framing. It involves the change in a stimulus function due to the derived arbitrary relations with other stimuli.

For instance, a boy who is told “chess is the game of intelligence” may begin to show an inclination towards this game if “being intelligent” was previously established as a positive reinforcer. Winning a chess game can lead the child to derive thoughts with appetitive functions such as “I’m smarter than him” due to the developed fluency in framing events in comparison. However, when losing a chess game, the child may also derive thoughts with aversive functions such as “I’m dumb” due to the opposite relationships between winning vs. losing and smart vs. dumb.

Things become even more complex when developing fluency in hierarchical framing. This type of framing allows the gradual construction of increasingly abstract positive reinforcers (i.e., values) that will contain goals, objectives, and tangible reinforcers. Let’s see an example following the article by Ruiz et al. (2020). The left panel of Figure 1 depicts a hierarchical relational network of positive reinforcers in which having a “meaningful life” consists of developing trustful friendships, literature knowledge, and literacy skills. These abstract positive reinforcers contain objectives and actions such as telling problems and concerns to friends, developing common projects, sharing time, reading novels frequently, writing own novels, and teaching literature. The thoughts and actions signalling these hierarchical positive reinforcers will acquire appetitive functions due to the transformation of functions through hierarchical relations (Gil et al., 2012). For instance, sharing a problem with a friend will acquire appetitive functions that might counteract experiencing aversive feelings while telling it.

Figure 1. Hierarchical networks of positive reinforcers (left) and negative reinforcers (right) that are related in opposition.

The construction of hierarchical networks of positive reinforcers dramatically changes the source of joy in human beings, which becomes increasingly verbal, symbolic, and abstract. Primary reinforcers lose relevance in controlling human behavior because they are even modified by verbal means (e.g., the preferred meal functions might be modified when relating it to future health issues). Similarly, suffering also becomes primarily verbal because the individual will derive a relational network of negative reinforcers related in opposition to the network of values. This network will become the “other side of the coin” of values (Gil-Luciano et al., 2019).

The right panel of Figure 1 depicts a relational network of negative reinforcers. In this case, a meaningless life for the individual would consist of not developing trustful relationships, literature knowledge, and literacy skills. As in the other network, the thoughts and actions signaling these hierarchical negative reinforcers will acquire aversive functions. For instance, when experiencing the rejection of some proposals to hang out with friends, the individual could derive “They don’t want to spend time with me,” which will acquire aversive functions because it is hierarchically related in opposition to the value of developing intimate friendships.

In the last paragraphs, I have tried to explain the verbal origin of human joy and suffering in a simple way. However, appetitive and aversive thoughts are only transitory events. So, why do some human beings develop a meaningful life while others a life full of suffering? The response to this question seems to be related to how we respond to these appetitive and aversive functions. Törneke et al. (2016) identified two main forms in which individuals respond to these events. The first is the most simple type and involves responding under the control of the derived functions of the events (i.e., responding in coordination with their discriminative functions). When thoughts and emotions have aversive functions, the predominant reaction is to engage in some behavior that aims to reduce these functions (i.e., some form of experiential avoidance). The problem with this type of responding is that it is “blind” to values, and, when becoming the predominant form of responding, it tends to provoke a paradoxical effect.

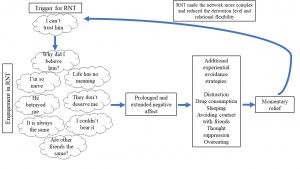

For instance, repetitive negative thinking (RNT) in the form of worry and rumination tends to be the first reaction to aversive thoughts and emotions due to our extremely sophisticated relational framing skills. RNT usually prolongs and intensifies the aversive functions because most of the thoughts involved in this process also have aversive functions. This prolonged negative affect usually leads to engaging in other experiential avoidance strategies that finally reduce aversive functions. However, RNT increases the complexity of the relational networks involved in this process, which facilitates deriving a thought that will initiate a new RNT process. Furthermore, when this cycle is repeated, the networks’ derivation level decreases, which is associated with a higher rapidity and automaticity of the thinking process. Lastly, relational flexibility is also reduced, which is related to experiencing more difficulties in disengaging from RNT. Figure 2 shows an example of this vicious loop that traps the individual in an inflexible pattern of behavior characterized by suffering. In other words, suffering in human beings seems to be related to a pattern of behavior mainly under the control of hierarchical negative reinforcers.

Figure 2. A vicious loop of RNT and its consequences.

The second type of responding to thoughts and emotions is more flexible and entails framing them in hierarchy with the deictic “I,” which allows other sources of stimulus control to enter in the stage. Said another way, framing ongoing thoughts and emotions in hierarchy (i.e., discriminating them as transitory events that the individual is experiencing) permits deriving rules that specify actions signaling hierarchical positive reinforcers (i.e., appetitive augmentals) and behavior according to them. When this type of responding becomes the main response to thoughts and emotions, the individual’s behavior will be mainly controlled by positive reinforcement. In other words, developing a joyful and meaningful life in human beings seems to be related to a pattern of behavior mainly under the control of hierarchical positive reinforcers even when experiencing aversive thoughts and emotions sometimes.

In this blog entry, I have tried to summarize an RFT approach to human joy and suffering. The previous conceptualization has influenced the design of brief interventions based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999; Wilson & Luciano, 2002) and focused on dismantling dysfunctional patterns of RNT. Preliminary empirical evidence indicates that RNT-focused ACT protocols are being highly efficacious in treating emotional disorders.

References

Gil, E., Luciano, C., Ruiz, F. J. y Valdivia-Salas, S. (2012). A preliminary demonstration of transformation of functions through hierarchical relations. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 12, 1-20. https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen12/num1/313/a-preliminary-demonstration-of-transformation-EN.pdf

Gil-Luciano, B., Calderón-Hurtado, T., Tovar, D., Sebastián, B., & Ruiz, F. J. (2019). How are triggers for repetitive negative thinking organized? A relational frame analysis. Psicothema, 31, 53-59. http://www.psicothema.com/psicothema.asp?id=4514

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame theory. A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Kluwer Academic Press.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy. An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press.

Ruiz, F. J., Luciano, C., Flórez, C. L., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., & Cardona-Betancourt, V. (2020). A multiple-baseline evaluation of RNT-focused acceptance and commitment therapy for comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 356. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00356/full

Törneke, N., Luciano, C., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Bond, F. W. (2016). Relational frame theory and three core strategies in understanding and treating human suffering. In R. D. Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of contextual behavioral science (pp. 254-272). Wiley-Blackwell.

Wilson, K. G., & Luciano, C. (2002). Terapia de Aceptación y Compromiso. Un tratamiento conductual orientado a los valores [Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. A values-oriented behabioral treatment]. Pirámide.

List of published RNT-focused ACT studies (chronologically ordered)

Ruiz, F. J., Riaño-Hernández, D., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., & Luciano, C. (2016). Effect of a one-session ACT protocol in disrupting repetitive negative thinking. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 16, 213-233. https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen16/num3/443/effect-of-a-one-session-act-protocol-in-EN.pdf

Ruiz, F. J., Flórez, C. L., García-Martín, M. B., Monroy-Cifuentes, A., Barreto-Montero, K., García-Beltrán, D. M., Riaño-Hernández, D., Sierra, M. A., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., Cardona-Betancourt, V., & Gil-Luciano, B. (2018). A multiple-baseline evaluation of a brief acceptance and commitment therapy protocol focused on repetitive negative thinking for moderate emotional disorders. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 9, 1-14. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212144718301170

Ruiz, F. J., García-Beltrán, D. M., Monroy-Cifuentes, A., & Suárez-Falcón, J. C. (2019). Single-case experimental design evaluation of repetitive negative thinking-focused acceptance and commitment therapy in generalized anxiety disorder with couple-related worry. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 19, 261-276. https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen19/num3/521/single-case-experimental-design-evaluation-EN.pdf

Dereix-Calonge, I., Ruiz, F. J., Sierra, M. A., Peña-Vargas, A., & Ramírez, E. S. (2019). Acceptance and commitment training focused on repetitive negative thinking for clinical psychology trainees: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 12, 81-88. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212144718303302

Ruiz, F. J., Luciano, C., Flórez, C. L., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., & Cardona-Betancourt, V. (2020). A multiple-baseline evaluation of RNT-focused acceptance and commitment therapy for comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 356. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00356/full

Ruiz, F. J., Peña-Vargas, A., Ramírez, E. S., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., García-Martín, M. B., García-Beltrán, D. M., Henao, A. M., Monroy-Cifuentes, A., & Sánchez, P. D. (2020). Efficacy of a two-session repetitive negative thinking-focused acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) protocol for depression and generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized waitlist control trial. Psychotherapy, 57, 444-456. https://content.apa.org/record/2020-02082-001

Salazar, D. M., Ruiz, F. J., Ramírez, E. S., & Cardona-Betancourt, V. (2020). Acceptance and commitment therapy focused on repetitive negative thinking for child depression: A randomized multiple-baseline evaluation. The Psychological Record, 70, 373-386. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40732-019-00362-5

Bernal-Manrique, K. N., García-Martín, M. B., & Ruiz, F. J. (2020). Effect of acceptance and commitment therapy in improving interpersonal skills in adolescents: A randomized waitlist control trial. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 86-94. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212144720301551