5 years ago, Cory Monteith – most famous for his acting role in Glee, passed away in a Vancouver hotel room. His cause of death was drug toxicity from a mixture of heroin and alcohol. His death was highly publicized but this was due to his public popularity, not because overdoses are rare events. In fact – it’s quite the opposite.

I can hardly go a few days without hearing another story. Recently Demi Lovato, an American singer/actress, had a near-fatal overdose and is now in rehab. Shortly after I found out that a friend from Michigan died from a heroin overdose – no one even knew he was using. Then, a few weeks back, rapper Mac Miller died from an apparent overdose.

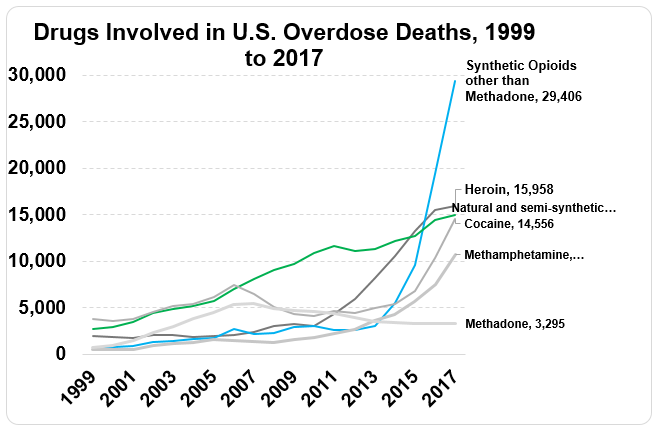

There are several reasons why overdoses can occur, but there’s no question that overdose fatalities have increased in recent years. Since my last post the Center for Disease Control updated the statistics for 2017 indicating that over 72,000 Americans died from overdoses, which is a 2-fold increase over the past ten years (see figure, source: CDC WONDER). It’s notable that while there’s an increase in overdoses with nearly each drug type, the sharpest increase in recent deaths have been from synthetic opioids including fentanyl and fentanyl analogs.

Synthetic means that the drug is man-made. While fentanyls have a range of potencies, many are fast-acting and strong even with a VERY small dose (see graphic below). Without laboratory testing it’s impossible to know whether cocaine or heroin is “laced” with fentanyl, so some users simply are unaware of what they’re taking. In those cases, an overdose may occur because drug can overwhelm the body – the respiratory system, quickly leading to lower heart rate and slowed (or stopped) breathing.

Beyond these cases in which a person may simply be unaware of what drug they’re taking or of what quantity, users can sometimes overdose even when taking the same dosage of the same drug they habitually consume. This may seem difficult to fathom if you only view drugs pharmacologically or metabolically – as in, if you were able to handle a certain drug dose yesterday and the day prior and the day prior then why not today?

As I began discussing in the last blog post – your body has the amazing ability to learn about meaningful events and even to anticipate your next move based on your prior actions. We’re able to naturally associate reliable environmental stimuli (such as drug paraphernalia) with important events (e.g., heroin use) and, after learning this association, our body prepares and can compensate for the upcoming drug. Thanks to classical conditioning, when we’re in the presence of stimuli that have previously predicted drug use, our bodies can begin to produce effects that are at odds with the drug effect to essentially dampen or mute it. This contributes to the development of drug tolerance – where you need to take a larger dose of a drug to receive the same subjective effects. However, if you deviate and are not in the presence of a similar context when you take a drug… this can have dire consequences.

To provide several examples of interesting research that has investigated this general phenomenon:

A pain med such as morphine produces a decreased sensitivity to pain – called analgesia – essentially allowing us to tolerate more painful stimuli when taking the drug. If you’ve been hospitalized prior, it’s likely that you’re familiar with morphine. However, researchers (e.g., Siegel, 1975) have found that giving just a few injections of morphine in the same environmental context leads to hyperalgesia (a heightened sensitivity to pain) upon being re-exposed to that environment.

This conditioned compensatory response can also apply to drugs many people commonly enjoy – such as your morning coffee or evening wine. Alcohol, for example, produces an unconditioned response of expanded blood vessels which causes you to lose heat more rapidly (… despite you perhaps feeling warm and fuzzy when drinking). But upon conditioning to environmental cues such as the taste of alcohol or even time of day, your body can start to compensate producing hyperthermia – an above normal body temperature (Crowell et al., 1981).

Beyond producing a subjective “alertness”, caffeinated beverages also increase saliva. However, for regular coffee drinkers a decrease in saliva production is initiated upon us sensing the reliable environmental cues of the impending coffee intake (e.g., scent, morning routine) to compensate for the upcoming increase. Perhaps luckily, research has not reliably shown that there is tolerance or compensation for the heightened alertness that caffeine also produces… meaning that smelling your coworker’s coffee isn’t going to decrease your ability to focus intently at work. Though, smelling it might make your mouth a bit dry.

And while you’re unlikely to overdose on caffeine, some other drugs produce effects that push the pleasurable dose close to the lethal dose. When this is combined with the compensatory effects produced by classical conditioning, a person can overdose just by taking the same dose they’d typically consume.

Let’s imagine a person who typically uses a drug such as heroin at home. There are several “home” stimuli that can become conditioned to predict heroin use. If that person were to go to new environment – perhaps a party or a hotel – and administers the same amount they typically would at home, since no compensatory responses will be produced that same dose will produce stronger effects than typical. And depending on the drug effects that otherwise would’ve been dampened, these effects can overwhelm the respiratory system and prove to be fatal. Indeed, Siegel (1984) collected data from survivors of near-fatal overdoses who frequently reported that the circumstances of the drug use were different from the conditions they normally would consume the drug.

Not all overdoses are due to classical conditioning “gone wrong”. However, depending on the circumstances it certainly plays a role. Furthermore, this compensatory reaction is not limited to illicit drugs. Researchers have found that patients who visit a hospital setting for chemotherapy treatments can exhibit immunosuppression (such as anticipatory nausea and vomiting) upon seeing and entering the hospital setting.

What can be done to weaken these compensatory responses? Well – a lot, but that’s probably best left to discuss in another post.