The Double Edged Sword of Human Language and Cognition: Shall We Be Olympians or Fallen Angels?

Guest Blog by Dermot Barnes-Holmes, Ghent University

(Blog based on the 2018 SQAB/ABAI Tutorial)

In his 1982 novel, “Before She Met Me”, the famous English author, Julian Barnes opens with the following quotation:

“Man finds himself in the predicament that nature has endowed him essentially with three brains which, despite great differences in structure, must function together and communicate with one another. The oldest of these brains is basically reptilian. The second has been inherited from the lower mammals, and the third is a late mammalian development, which . . . has made man peculiarly man. Speaking allegorically of these brains within a brain, we might imagine that when the psychiatrist bids the patient to lie on the couch, he is asking him to stretch out alongside a horse and a crocodile.”

Paul D. MacLean, Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases,

Vol. CXXXV, No 4, October 1962

The novel tells the story of a mild-mannered, reserved, middle-aged English academic historian, Graham Hendrick, who finds himself trapped in a loveless marriage and as the old saying goes, living a life of quiet desperation. The narrative unfolds when he begins an affair with another women, divorces his wife and then re-marries. The second marriage appears to possess all that the first one did not, but alas his new wife, Ann, has “a past” as a B-movie actress who had her fair share of on-screen and off-screen affairs and sexual encounters. Although Graham and Ann are very much in love and completely faithful to each other, Graham gradually develops an obsessive jealousy over Ann’s previous sexual partners. The novel describes Graham’s frightening and tragic descent into a self-destructive madness, as he struggles with what he himself sees as a completely irrational reaction to Ann’s past.

The novel thus provides a tour de force of the core paradox of human psychology – even when we have everything that could possibly make us happy, it is only too easy to find reasons, sometimes even completely irrational ones, to make ourselves utterly miserable. This Blog, Acting and Relating, is devoted, in part, to presenting a behavior-analytic approach to understanding and treating this peculiarly human capacity for psychological suffering. The appeal to three brains presented at the beginning of Julian Barnes’ novel, as a cause or source of human psychological struggle, is of course as apocryphal as it is comical, but it also has a metaphorical side that may be useful in presenting a currently emerging behavioral understanding of the human condition. Allow me to explain.

Relating, Orienting, and Evoking: A Behavioral Unit of Analysis for Acts of Meaning

In a recent invited lecture in the SQAB/ABAI tutorial series (presented in San Diego), I outlined a conceptual development that is just emerging in my research group (www.GO-RFT.com). Specifically, we have begun to conceptualize psychological events for verbal humans as involving a constant behavioral stream of relating, orienting, and evoking, summarized as ROE-ing (pronounced “rowing’). In very simple terms, relating refers to the myriad complex ways in which language-able humans can relate stimuli and events; orienting refers to noticing or attending to a stimulus or event; and evoking refers to whether it is responded to as appetitive, aversive, or relatively neutral. The three elements of the ROE are not separable units of analysis but are “fuzzy” categories that work together in virtually every psychological act emitted by a verbally-able human. For illustrative purposes, imagine you are about to enter a forest with a tour guide who warns you, “Watch out for snakes with red and yellow stripes because they are quite aggressive and also highly venomous.” If the warning is understood, it may be conceptualized as involving an instance of relating (snakes with danger), which may increase the likelihood that you will orient towards any odd movement on the ground in the forest that could be a snake, followed by an appropriate evoked reaction, such as backing away, freezing, or beating it with a heavy stick if the moving object is perceived to be a snake with red and yellow stripes (i.e., a highly aversive stimulus). In effect, your reaction to the snake in the forest is conceptualized as involving the three elements of the ROE.

It important to understand that the three elements of the ROE do not necessarily interact in a linear or uni-directional manner, but are dynamical. Thus, for example, an orienting response may produce relating, which then leads to an evoked response. Imagine you entered the forest without hearing any warning about snakes. You might be less likely to orient towards snake-like movements, in the absence of the previous warning, but if you did notice a snake you may engage in some relational activity, such as emitting the self-generated rule “better safe than sorry” and with-drawing slowly. In this latter case, orienting led to relating, which led to evoking.

The examples of ROEing I have just provided are of course completely rational, in the sense that they would help you to avoid a potentially lethal snake-bite. But less healthy examples of ROEs are of course possible. In the novel, “Before She Met Me” Graham insists that when he and Ann take a summer holiday in Europe they avoid visiting any country or region in which she had previously spent time with a former lover. The verbal knowledge (relating) that Ann had previously spent time in a particular location with a former sexual partner thus transforms that location into an aversive stimulus because it would increase orienting responses towards Graham’s intense feelings of jealousy. Adopting an avoidance strategy “works” for that particular holiday, in that Graham and Ann enjoy their vacation by deliberately avoiding any location associated with Ann’s past life as an actress. But ultimately of course Graham is doomed to fall increasingly victim to his obsessive jealousy because the human capacity for relating stimuli and events knows no bounds, which is borne out in the remaining part of the novel to which we shall return later.

The concept of the ROE serves to highlight the inherent “design flaw” in human psychology. Our ability to orient very quickly towards a stimulus that may present some danger and then quite sensibly respond to that stimulus as aversive (by fleeing, freezing, or fighting) typically serves us and other animals quite well. But when combined with the human capacity for relating stimuli in increasingly abstract and complex ways (i.e., via human language), orienting and evoking may run amok and the human mind can literally drive itself mad as it struggles with “irrational” orienting and evoking responses.

So, where did this concept of the ROE come from? Well, it has emerged from working on the relationship between the two foci of this very blog, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and relational frame theory (RFT). In what follows, I will attempt to explain briefly how the concept of the ROE has emerged from RFT, through our recent empirical and conceptual research (go to www.GO-RFT.com to find out more about the background and details of this research activity).

I will not work through the history and concepts of RFT in detail here because they have been explicated elsewhere many times before (see Barnes-Holmes, Finn, Barnes-Holmes, & McEnteggart, 2018, for a recent review article that relates directly to the content of this particular blog). I will, however, attempt to provide sufficient background information so that the recent conceptual developments may be readily understood.

Relational Frame Theory

Basic Relational Framing

Relational frame theory emerged directly from the seminal work of Murray Sidman on what he called stimulus equivalence (see Sidman, 1994, for a book-length review). The basic stimulus equivalence effect was defined as the emergence of unreinforced or untrained matching responses based on a small set of trained responses. For example, when a person was trained to match two abstract stimuli to a third (e.g., A-B and A-C), untrained matching responses frequently appeared in the absence of additional learning (e.g., B-C and C-B). When such a pattern of unreinforced responses occurred, the stimuli were said to form an equivalence class or relation. Importantly, this behavioral effect appeared to provide the basis for a functional-analytic definition of symbolic meaning or semantic reference. In other words, a written or spoken word could only be defined as a symbol for an object or event if it participated in an equivalence class with that other stimulus.

Relational frame theory appeared to provide an important extension to the work on stimulus equivalence (see Hughes & Barnes-Holmes, 2016a, 2016b, for recent extensive reviews). Specifically, the theory argued that stimulus equivalence may be considered a generalized relational operant, and many different classes of such operants were possible, and indeed common in natural human language. According to this view, exposure to an extended history of relevant reinforced exemplars serves to establish particular patterns of generalized relational (operant) response units, defined as relational frames. For example, a young child would likely be exposed to direct contingencies of reinforcement by the verbal community for pointing to the family cat upon hearing the word “cat” or the specific cat’s name (e.g., “Tibbles”), and to emit other appropriate naming responses, such as saying “Tibbles” or “cat” when the family pet was observed, or saying “Tibbles” when asked, “What is the cat’s name?” Across many such exemplars, involving other stimuli and contexts, eventually the operant class of coordinating stimuli in this way is established, such that direct reinforcement for all of the individual components of naming are no longer required when novel stimuli are encountered. Imagine, for example, that the child was shown a picture of a platypus, and the written word, and was told its name. Subsequently, the child may say “That’s a platypus” when presented with a relevant picture or the word without any prompting or direct reinforcement for doing so. In other words, once the generalized relational response of coordinating pictures, spoken stimuli, and written words is established, directly reinforcing a subset of the relating behaviors “spontaneously” generates the complete set. Critically, when this pattern of relational responding has been established, the generalized relational response may then be applied to any stimuli, given appropriate contextual cues.

Contextual cues are thus seen as functioning as discriminative for particular patterns of relational responding. The cues acquire their functions through the types of histories described above. Thus, for example, the phrase “that is a”, as in “That is a cat”, would be established across exemplars as a contextual cue for the complete pattern of relational responding (e.g., coordinating the word “cat” with actual cats). Similarly, phrases such as “That is not a”, or “That is bigger than” or “That is faster than” would be established across exemplars as cues for other patterns (or frames) of relational responding. Once the relational functions of such contextual cues are established in the behavioral repertoire of a young child, the number of stimuli that may enter into such relational response classes becomes almost infinite.

Contextual cues are also seen as critical in controlling the behavioral functions of the stimuli that are produced in any instance in which stimuli are related. For example, the word “cat” could produce different responses for a child if she was asked “what does your cat look like” versus “feel like”. In RFT, therefore, two broad classes of contextual cues are involved in any instance of relational framing – one class controls the type of relational response (e.g., equivalence) and the other cue controls the specific behavioral functions of the stimuli that are produced during the act of relating; these two classes of contextual cue are denoted Crel and Cfunc, respectively.

The core analytic unit of the relational frame is defined as possessing three properties; mutual entailment (if A is related to B then B is also related to A), combinatorial entailment (if A is related B and A is related to C, then B is related to C, and C is related to B), and the transformation of functions (the functions of the related stimuli are changed or transformed based upon the types of relations into which those stimuli enter). The third property, the transformation of functions, marks a substantive and important extension to the concept of equivalence relations. Specifically, it ensures that the concept of the relational frame always refers to some change or modification in the behavioral functions of the framed stimuli that extend beyond their relational functions per se. For example, if A is more than B and B is more than C in a particular instance of relational framing, and a reinforcing function is attached to A, then C may acquire a reduced reinforcing function relative to A or B. The concept of a relational frame was thus designed to capture how human language and cognition changes our reactions to the “real” world around us rather than simply providing, for example, an analysis of logical or abstract human reasoning.

According to RFT, many of the functions of stimuli that we encounter in the natural environment may appear to be relatively basic or simple but have acquired those properties due, at least in part, to a history of derived relational responding. Even a simple tendency to orient strongly towards a particular stimulus in your visual field may be based on relational framing. Consider the earlier example of a “startle response” to the movement of a snake because a native speaker recently coordinated “snakes” with “highly venomous.” Such functions may be defined as Cfunc properties because they are examples of specific stimulus functions (i.e., orienting/startle) that are acquired based on, but are separate from, the entailed relations (Crel properties) among the relevant stimuli.

Relational Networks, the Verbal Self, and the ROE as an Act of Meaning

According to RFT, a child’s on-going interactions with the verbal community establish increasingly complex networks involving coordination and temporal relations with contextual cues that transform specific behavioral functions. Some of these networks may be rules or instructions, such as “If the light is red then stop”. This rule involves frames of coordination between the words “light”, “red”, and “stop” and the actual events to which they refer. In addition, the words “if” and “then” serve as contextual cues for establishing a temporal relation between the red light and the act of stopping (i.e., first red light then stop). The relational network thus transforms the functions of the red light itself, such that it now controls the act of “stopping” whenever a child who was presented with the rule observes a red light.

Additional levels of complexity in derived relational responding are also established through a child’s on-going interactions with the verbal community. For example, relating relations, and relating relational networks, are seen as critical when children learn to reason analogically and engage in increasingly complex problem solving. Consider, for example, the analogy, apple is to orange as goat is to sheep. In this example, there are two relations coordinated through class membership (controlled by the cue is to) and a coordination relation that links the two coordination relations (controlled by the cue as). From an RFT point of view, analogical reasoning thus involves the same behavioral process involved in relational framing more generally, but applied to framing itself.

Another area in which RFT argues that human language (defined in terms of increasingly complex relational networks) plays a critical role is in the development of a sense of self. Specifically, a “verbal” self involves three deictic relations: the interpersonal relations I-YOU, spatial relations HERE-THERE, and temporal relations NOW-THEN. The core postulate here is that as children learn to respond in accordance with these relations, they are in essence learning to relate the self to others in the context of particular times and places. Imagine a very young child who is asked “What did you have for breakfast today?” while they are eating an evening meal with their family. If the child responded simply by referring to what the family is currently having for dinner, they may well be corrected with “No, that’s what we are all eating now for dinner, but what did you eat this morning?” In effect, this kind of on-going refinement of the three deictic relations allows the child to respond appropriately to questions about their own behavior in relation to others, as it occurs in specific times and specific places.

It should be emphasized that the verbal self, as defined by RFT, is best thought of as a dynamical and complex relational network, rather than a basic or simple relational frame. As the foregoing example illustrates, an advanced level of verbal ability or derived relational responding on behalf of the young child is required in order for the verbal community to establish and refine a verbal self for that child. Furthermore, the self-referential terms (e.g., “I,” “me,” “self,” “mine” the child’s name, etc.) come to participate in a complex network of relational responses some of which are more constant than others. For example, the statement or network “I am older than my brother but younger than my sister” is unlikely to change once it is established, whereas other self-related networks are more “fluid” (e.g., “Today I feel really sick, but tomorrow I might feel better”). In this sense, it is useful to think of the verbal self as lying at the very center of a vast and undulating web of derived relations, some of which almost never change, with others emerging and disappearing as determined by a host of contextual cues and variables.

Once a verbal self is established in the behavioral repertoire of an individual it becomes a stimulus or on-going event that participates in virtually every ROE. The vast majority of these ROEs may be seen as relatively trivial in the grand scheme of things, but the verbal self remains a participant in such acts. For example, the relating, orienting, and evoking that occurs in the act of switching off a bedroom lamp before going to sleep could be seen as extremely trivial, but it is still a “verbal you” who turns off the lamp to achieve some outcome (i.e., a good night’s sleep). Other ROEs, of course, may be seen as far more fundamental, and clearly are self-focused. For example, the relating, orienting, and evoking that occurs in the act of taking an overdose to end one’s life could be seen as an attempt to escape, in a very permanent and final way, the very essence of the verbal self. In any case, the constant and iterative daily cycle of ROEing, from the most trivial to the most fundamental of human acts, could be seen as creating what philosophers and others have called a sense of purpose or meaning to one’s life.

The concept of the ROE thus provides a general conceptual unit of analysis, based on RFT, that aims to capture the distinct way in which most humans navigate their psychological worlds. In a broad sense, the ROE, as a unit of analysis, sees human “acts of meaning” as emerging through the evolution of human language, and through our on-going interactions with the verbal communities in which we reside from birth through to death. The complexities involved in learning to engage in such acts of meaning are far from simple and in my SQAB/ABAI tutorial I presented an RFT-based framework for conceptualizing and analyzing the dynamics involved in human acts of meaning, named the hyper-dimensional multi-level (HDML) framework. As an aside, the HDML is an extension of the MDML framework (see Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, Luciano, & McEnteggart, 2017, for a detailed treatment of the latter). The HDML replaces the M (“multiple) with H (“hyper”) in order to emphasize the relating and functional properties of acts of meaning as defined within the ROE itself. The reader might also note that the HDML arose, in part, by integrating the MDML with a recent model my research group had developed, called the Differential Arbitrarily Applicable Relational Responding Effects (DAARRE) model (Barnes-Holmes, Finn et al., 2018). In the interest of brevity, I have not covered the model or relevant empirical research here (but go to www.GO-RFT.com, for relevant material).

The HDML, Acts of Meaning, and Human Psychological Suffering

One of the purposes of the HDML is to provide a framework that outlines how the simpler units of analysis specified in RFT, such as mutual entailment, which is relevant to naming, connect to the more complex units, such as the relating of relational networks, which is seen as critical to “full-blown” acts of meaning. A very brief outline of the framework is presented below before illustrating how it can help to conceptualize the importance of ROEs, or acts of meaning, in understanding human psychological suffering.

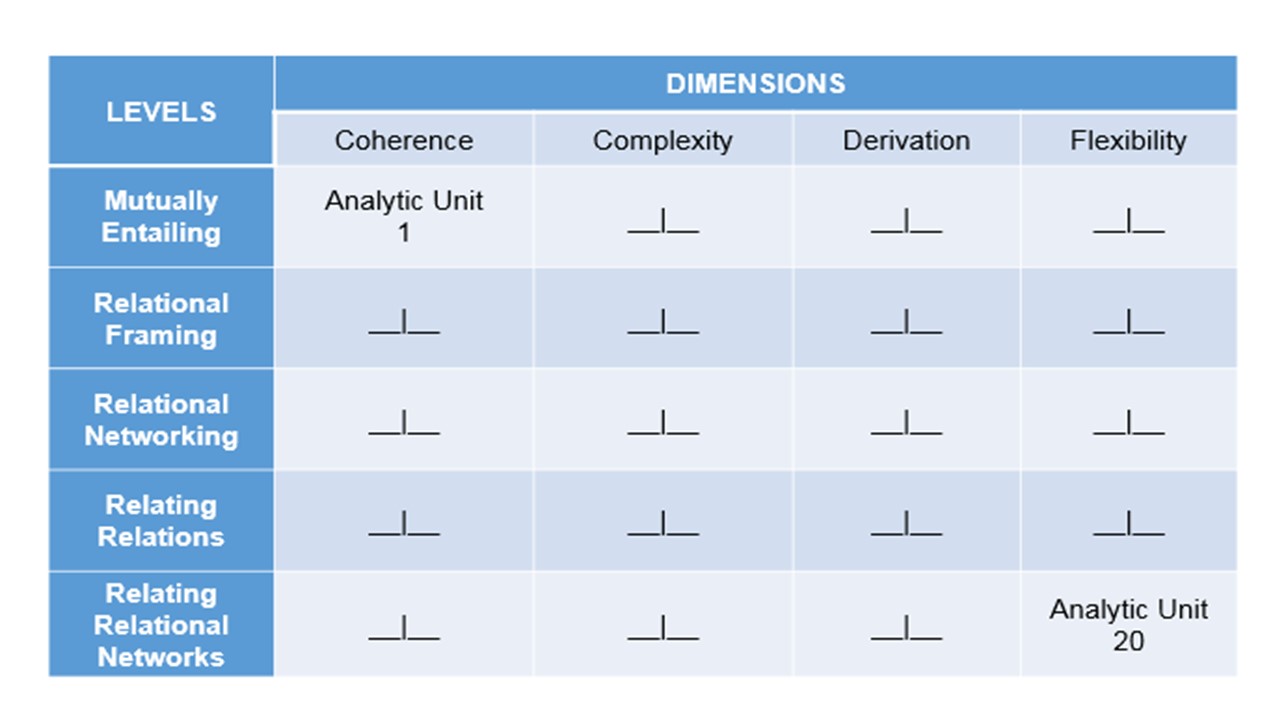

The HDML specifies five levels of relational responding: mutual entailing; relational framing (the simplest type of relational network); relational networking; relating relations; and relating relational networks. In addition, the framework conceptualizes four dimensions for each of these five levels: coherence, complexity, derivation, and flexibility (see Table 1). Each level intersects with each dimension yielding a total of 20 units of experimental analysis, which it has been argued emphasizes the highly dynamical nature of derived relational responding involved in human language and cognition. Coherence refers to the extent to which current relational responding is broadly consistent with previous patterns of relational responding (whether they are directly trained or derived). Complexity refers to the detail or density of a pattern of relational responding, including the number or types of relations in a given relational network. Derivation refers to the number of times a derived response has been emitted; the first response is high in derivation because it is being derived entirely from a trained relation, but thereafter derived responding gradually acquires its own history and is, therefore, less and less derived relative to the initial relation that was trained. Flexibility refers to the extent to which patterns of derived relational responding may be influenced or changed by contextual variables (e.g., when trained baseline relations are reversed).

Table 1. A Hyper-Dimensional Multi-Level Framework, which extends the MDML by emphasizing the relating and functional properties of the ROE as a unit of analysis in RFT.

I will now focus on how the HDML could help to conceptualize ROEs or acts of meaning in the context of psychological suffering. To do so, let us return to the main protagonist, Graham, in Julian Barnes’s novel. Imagine that Graham goes to see a psychotherapist for help with his obsessive jealousy (in the novel Graham does not do so). Early in therapy, Graham says, “I have become obsessively jealous about my wife’s previous lovers.” The therapist asks, “Do you feel jealous all of the time?” and Graham replies “Oh yes, the jealousy never goes away – it dominates my every waking hour.” The therapist then asks, “How long have you felt like this?” and Grahams replies, “Almost from the first day I met my wife – she has always been very open and honest about her past life — and although we’ve been married for a few years now, my jealous feelings seem to be getting worse rather than better.” The therapist then asks, “Why do you think you are so obsessively jealous?” to which Graham replies, “I don’t know really, I just am.” Finally, the therapist asks, “Do you think that your jealousy could fade away with time?” to which Graham reacts angrily with, “If I thought that do you think I would have bothered to come to see you?”

Within the framework of the HDML, we could conceptualize this therapeutic interaction as follows. Graham’s first statement, “I have become obsessively jealous. . .” involves mutually entailing the verbal self (i.e., words and terms, such as “I” “self” and “Graham Hendricks”) with “jealous.” Graham’s next statement “. . . the jealousy never goes away. . .” suggests that the relational responding is high in coherence in the sense that it coheres strongly with virtually all other self-statements. Graham’s answer to the question about how long he has felt this way (“Almost from the first day I met my wife”) suggests that the relational responding is also low in derivation, because he has been focused on his jealousy for years. When asked why he is so jealous, the reply “I don’t know really, I just am” suggests that the relational responding is low in complexity. Graham’s angry reaction to the therapist’s final question about the jealousy possibly fading away with time suggests that the relational responding is low in flexibility. (In the interests of brevity, the foregoing interpretation focuses simply on the four dimensions of the HDML rather than the intersections between the dimensions and the levels of relational responding. In general, however, it seems likely that therapeutic interactions such as the one above, often involve relational networking, relating relations, and relating relational networks; see Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & McEnteggart, 2018).

The relative precision the HDML provides in defining acts of meaning may be appreciated in considering how subtle differences in Graham’s responses might be interpreted. Imagine that when the therapist asked “Do you feel jealous all the time?” Graham had replied “No, I can see many reasons not to be jealous and that I am just being stupid when I feel that way.” This could suggest responding that is low in coherence (rather than high), because it is inconsistent with other examples of Graham’s relational networking with regard to his current wife. Imagine also that after being asked how long he had felt this way, Graham had responded “I only started feeling really jealous in the past few months” (rather than “Almost since the first day. . .”). Such a response could be interpreted as relatively high in derivation, because it emerged only recently in Graham’s relational responding. Imagine, also, if Graham had provided a list of reasons why he is so jealous (rather than simply saying, “I just am”); for example, if Graham had said “My mother and father divorced when I was young because my mother had an affair, and my first wife cheated on me, and I never really understood women anyway.” In this case, the relational responding may be seen as relatively high rather than low in complexity. Finally, imagine if in response to the therapist’s last question concerning the possibility that the jealousy could fade with time, Graham had replied calmly “I suppose so, it’s possible – do you think that might happen?” This response, instead of the angry retort, would suggest the relational responding may be relatively high in flexibility.

In the foregoing, I have offered various interpretations of Graham’s hypothetical responses by focusing on the entailing or relational properties of the HDML. But acts of meaning in RFT, or ROEs, require focusing also on the functional properties of the relational responding. More informally, Graham’s “problem” of obsessive jealousy is not just something he talks about in therapy – it is a psychological issue that impacts upon how he lives his day-to-day life. To reflect this, any pattern of relational responding captured within the 20 analytic units of the HDML also involves orienting and evoking functions. These are represented in each cell by the inverted “T” shape. The vertical line represents the relative value of orienting functions from low to high and the horizontal line represents the relative value of evoking functions from extremely aversive (on the far left) to extremely appetitive (on the far right). Within the context of the ROE, these functions impact upon, and are impacted by, the relational properties highlighted within each of the 20 units of the HDML. And virtually any contextual variable may be involved in influencing the dynamical interplay among the three properties within or across cells. Indeed, at the end of the Julian Barnes’ novel, an example of the “darkest side” of ROEing is graphically narrated.

The final pages of the book end with Graham orienting towards a moment of innocent flirtation between his wife and a mutual friend, Jack, who writes low-grade fiction for a living. Fuelled once again with raging jealousy, Graham searches obsessively through Jack’s past novels and concludes correctly from specific descriptions of sexual encounters contained therein that Jack and Ann had had a sexual encounter at some point in the distant past, but also derives, in complete error, that they are currently having an affair. Graham at this point has “related” himself into a black hole of obsessive jealousy from which he cannot escape. So crushed is he by this obsession that Jack has now become such an aversive stimulus that he calls to Jack’s house and butchers him to death with a carving knife, and sits all night waiting for Ann to call to Jack’s house, which eventually she does (hoping to find Graham). Upon arrival, Graham brings her in to the living room sits her in a chair, and then cuts his own throat and bleeds to death in front of her. Alas, Graham’s ROEing has caused his own existence to become so aversive that he attacks it in much the same way that one might attack a deadly snake with a machete. The novel ends with Ann breaking a window in Jack’s house and screaming for help with the blood soaked bodies of her erstwhile lover, Jack, and her deranged dead husband, Graham, surrounded by pools of their own blood. The narrative is thus complete and another tragic tale of the paradox of the human condition is told. Metaphorically, Graham ROEed himself into the psychological rapids of a dangerous river and over the edge of a large and deadly water-fall.

Epilogue

Both RFT and ACT adopt the position that the evolution of human language is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it allowed a relatively weak and slow-moving primate (i.e., humans) to develop virtually all of the benefits of the modern world in which we now live. On the other hand, human language and cognition allow us to create almost countless reasons to despair, even when there appears to be every reason to be happy and content. Metaphorically, humans can literally reach for the stars and live as Olympians or perhaps fall like angels from heaven, and join the many other species who have long since faded into the distant history of our planet. Perhaps the evolution of the highly abstract form of derived relational responding that emerges with any complex system of social communication, such as human language, leads almost inevitably to the rapid demise of that species, as it depletes the resources that are needed to maintain its survival, or its members “relate” themselves into some tribal apocalyptic conflict that leaves no one standing. Alternatively, perhaps the on-going development of the behavioral sciences will help us to navigate the perilous rocks, rapids, and waterfalls of the “dark-side” of derived relating, and allow us to produce the technology we need to escape a planet that sooner or later will cease to provide a viable home for our species.

References

Barnes, J. (1982). Before she met me. London: Jonathan Cape.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes Y., Luciano, C., & McEnteggart, C. (2017). From the IRAP and REC model to a multi-dimensional multi-level framework for analyzing the dynamics of arbitrarily applicable relational responding. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(4), 434-445.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Finn, M., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & McEnteggart, C. (2018). Derived stimulus relations and their role in a behavior-analytic account of human language and cognition. Perspectives on Behavior Science. In press.

Barnes-Holmes, Y, Barnes-Holmes, D., & McEnteggart, C. (2018). Narrative: Its importance in modern behavior analysis and therapy. Perspectives on Behavior Science. In press.

Hughes, S. & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2016a). Relational frame theory: The basic account. In R.Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds), The Wiley handbook of contextual behavioral science(pp. 129-178), West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hughes, S. & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2016b). Relational frame theory: Implications for the study of human language and cognition. In R. D. Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds), The Wiley handbook of contextual behavioral science (pp. 179-226), West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sidman, M. (1994). Equivalence relations: A research story. Boston, MA: Authors Cooperative.