Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Through the Lens of Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968)

GUEST BLOG BY JONATHAN TARBOX, University of Southern California

As the excitement about Acceptance and Commitment Therapy builds inside the ABA community, one of the biggest questions that folks are curious about is how and whether ACT is ABA, versus clinical psychology, social work, family therapy, or some other discipline. Fully answering this question would require something more like a journal article than a blog post but just to stoke interest and get the conversation going, I thought it might be fun to hit Baer, Wolf, and Risley’s (1968) seven characteristics very briefly. After all, what better yardstick do we have than the foundation laid by these incredible pioneers 50 years ago? With the understanding that much more clarification is needed on each of the points below, join me in a fun exercise by considering each of the seven characteristics below. And as a warning, for the sake of space and time, I’m not going to cover foundational information about what ACT is, you are going to have to get that somewhere else!

As the excitement about Acceptance and Commitment Therapy builds inside the ABA community, one of the biggest questions that folks are curious about is how and whether ACT is ABA, versus clinical psychology, social work, family therapy, or some other discipline. Fully answering this question would require something more like a journal article than a blog post but just to stoke interest and get the conversation going, I thought it might be fun to hit Baer, Wolf, and Risley’s (1968) seven characteristics very briefly. After all, what better yardstick do we have than the foundation laid by these incredible pioneers 50 years ago? With the understanding that much more clarification is needed on each of the points below, join me in a fun exercise by considering each of the seven characteristics below. And as a warning, for the sake of space and time, I’m not going to cover foundational information about what ACT is, you are going to have to get that somewhere else!Applied

The main focus of ACT is to help people do more behaviors that enhance their quality of life, especially orienting folks to positive reinforcement more and negative reinforcement less. Smoke less cigarettes, spend less money on gambling, exercise more, spend more time with family, get off the couch, spend more time with friends, eat healthier, be present and commit to one’s relationships, etc. These behavioral changes are about as applied as it gets.

Behavioral

The only point of ACT is to increase committed actions, in the form of overt behavior, towards things people really care about in life. Lots of the ACT research published in clinical psychology journals has used self-report measures, evaluated in between-groups designs, but that’s because those are considered the gold standard measures in those scientific communities (and most scientific communities in the larger world outside behavior analysis). ACT targets rigid behavior patterns that include private events, but not for the sake of changing private events. In fact, the whole point is to spend less time engaging with one’s private events and more time engaging in socially meaningful overt behaviors. For example, if I feel anxious about reaching out to make a new friend, but I value having more friends, then what’s the point struggling with how I feel about it? How about just saying hi to someone? And if you want more ABA research that shows these overt behavior changes, rather than self-report measures, it’s coming. Recent single case design research on ACT done by behavior analysts has used direct measures of overt behaviors as the primary dependent variables and the results have been strong.

Analytic

Carefully evaluating whether or not ACT interventions are responsible for behavior change, and nothing else, is the cornerstone of ACT research. More than 200 randomized controlled trials have done this very well, resulting in ACT being considered an empirically supported intervention for many important behaviors by multiple independent bodies. In addition, the last five or so years of research have seen behavior analysts using single-case research design to evaluate the effects of ACT interventions on specific overt behaviors of individual people. Such research uses exactly the single-case research tactics that the concept of “analytic” was born from.

Effective

The only point of ACT is to change socially meaningful overt behaviors to a large enough degree to actually matter. Research has shown that ACT produces large changes in behavior, plenty large enough to make meaningful differences in the lives of people who practice it.

Conceptually Systematic

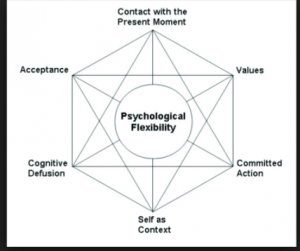

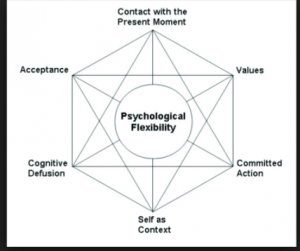

ACT was designed on the basis of behavior analytic principles, applied to analysis and intervention for complex verbal and rule-governed behavior. 100% of ACT procedures are analyzed and understood in terms of behavioral principles. However, as with any applied science, the practitioners implementing ACT are not all experts in behavioral conceptual analysis of complex verbal and rule-governed behavior. As a matter of fact, how many of us can really say we are? Because ACT was originally created by behavior analysts for the non-behavioral community (e.g., clinical psychology, etc.), the procedures were packaged with lay names (e.g., defusion, present moment awareness, values, etc.), which comprise the playfully named “hexaflex.” Each of these terms can be analyzed precisely with behavioral principles but these analyses are difficult. They should be difficult because we are talking about very complex human behavior! The need for ACT to be conceptually systematic with behavioral principles was the main reason why I, personally, wasted years before getting busy with ACT. I wanted to understand ACT the way I understand discrete trial training or functional communication training; tightly and with conceptual precision. That desire for conceptual precision is great but don’t let it get in the way of you learning more about it and trying a little piece of it here and there. Other really important areas of behavior analysis are confusing too (delay discounting, matching law, stimulus equivalence, etc.), but that shouldn’t prevent us from learning and growing as a science and a practice community. Reach out and learn, attend a workshop – or the ABAI ACT Seminar after the ABAI Annual Convention in San Diego!

Technological

This is perhaps the greatest challenge for ACT and, indeed, any complex treatment package within ABA. ACT consists of six main sets of procedures and their corresponding conceptual functional analyses: 1) Acceptance, 2) Present Moment Attention, 3) Self-As-Context, 4) Defusion, 5) Values, and 6) Committed Action. Each of these six consist of complex functional relations between verbal behavior, rule-governed behavior, and nonverbal behavior, in contact with derived verbal functions of stimuli, as well as nonverbal, direct functions of stimuli. Each of these six areas have scores of different procedures that can be used to move overt behavior in positive directions. And it all involves complex verbal behavior on the part of the behavior analyst. AND…a big part of ACT is being flexible, that is, NOT rigid and rote. Think about how hard it is to get perfect procedural integrity with even the simplest ABA procedures! So, being technological is a challenge for ACT, like any other complex package intervention. But many manualized ACT interventions exist and procedural integrity measures exist, so it is not impossible. And again, perfect procedural precision is difficult with other important areas of ABA, such as natural environment training and good quality parent training.

Generalized Outcomes

Generalization is perhaps one of ACT’s greatest strengths because ACT interventions establish what Skinner referred to as “secondary repertoires” of behavior – good habits of noticing one’s own behavior and responding to it in ways that support one’s own socially meaningful overt behaviors. These repertoires, by definition, are NOT under tight stimulus control. They are under broad, flexible contextual control and so can easily be transported to virtually any environment one finds oneself in. For example, the self-cue (stated to oneself overtly or covertly) “I’m here, now,” sometimes useful to self-monitor and orient one’s own attending behavior to be in the present, is applicable just about anywhere, anytime. Accordingly, it is not surprising that ACT research has pretty consistently found strong generalization and maintenance, sometimes with maintenance effects stronger than initial intervention effects.

In conclusion, this post was way too long for a blog post and too short for a journal article but I hope you found it fun and inspiring. I encourage you to continue the conversation by reading a book on ACT, attending a workshop, listening to a pod cast, or coming to the ABAI one day ACT seminar the day after the annual convention in San Diego! So, keep doing overt behaviors that matter to you and don’t believe your private events too much, they really aren’t that useful!