Author note: I thank Jonathan Kimball for helpful comments on a draft of this post.

A Darwinian Survival Guide: Hope for the 21st Century (2024), by Daniel R. Brooks and Salvatore J. Agosta. MIT Press.

From the publisher web site: Despite efforts to sustain civilization, humanity faces existential threats from overpopulation, globalized trade and travel, urbanization, and global climate change…. Brooks and Agosta offer a novel — and hopeful — perspective on how to meet these tremendous challenges by changing the discourse from sustainability to survival…. Our immediate goal ought to focus on preserving as many of humanity’s positive achievements—from high technology to high art—as possible to shorten the time needed to rebuild.

“The science of behavior can save the world!”

That rallying cry has echoed through our discipline for as long as I’ve been part of it. Skinner put the goal into writing in 1987’s Upon Further Reflection (and elsewhere), and we behavior analysts continue to discuss how to accomplish it (e.g., here and here; also Postscript 1).

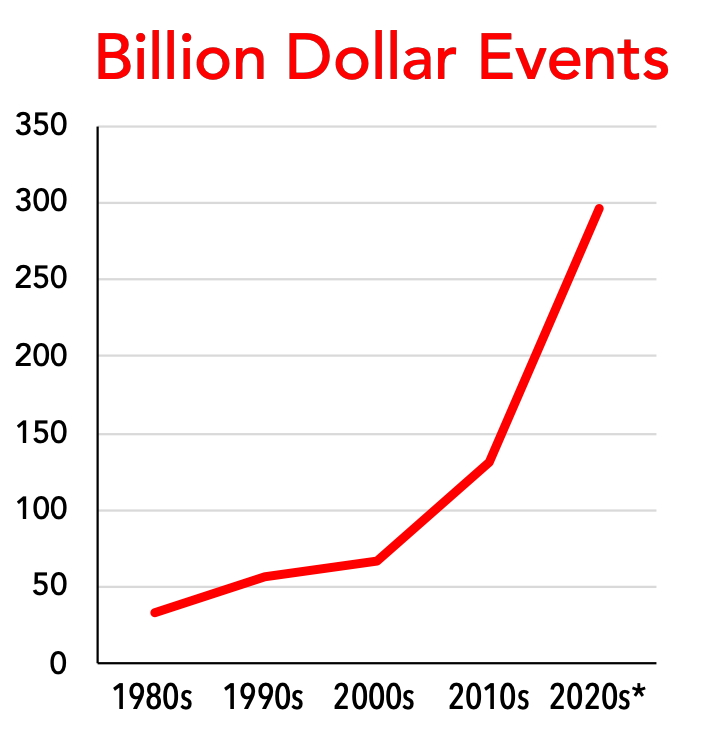

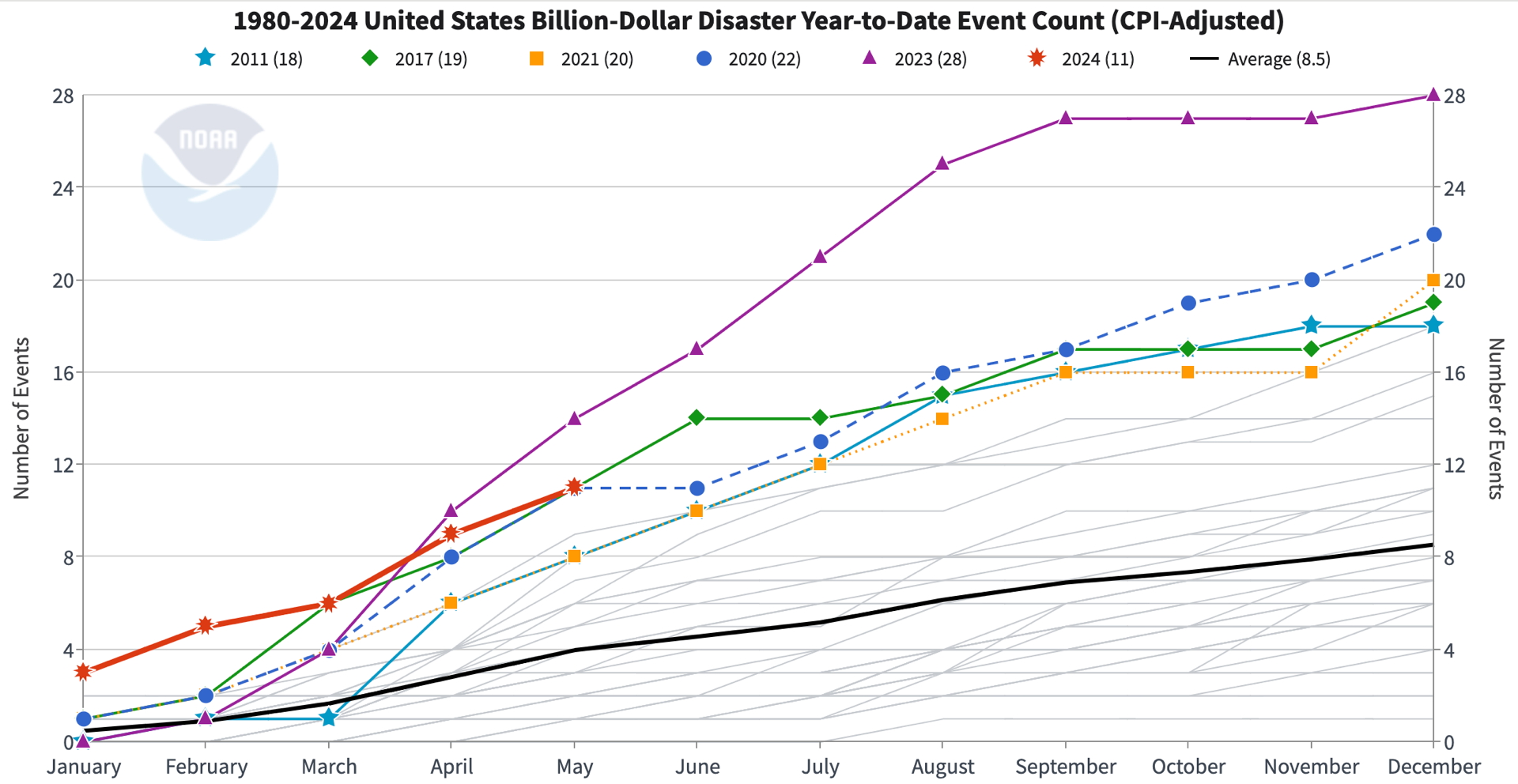

Yet in a very real sense the opportunity to save the world as we know it may have already passed. Glaciers are melting and seas are rising. Drought, storms, and heat waves are intensifying. As evidence of the latter, consider the frequency of major weather-related disasters, defined here as resulting in at least one billion US dollars of damage, in the United States over the past 45 years. To be clear, I’m not primarily interested in money, but financial cost is an objective marker for the harder-to-quantify toll in terms of damage to humans and their way of life (fwiw, weather-related deaths are increasing too). There’s been a pronounced uptick in weather disasters during the most recent decade — and the last full year for which data are available, 2023, was much worse than the preceding few years (Postscript 2).

Evidence like this fuels a growing scientific consensus that human-created climate change may have accelerated past a tipping point. If so, then climate disaster is now an inevitability, and human systems predicated on the world as it was may be at risk for collapse (though see Postscript 3). Some projections are for the worst to begin overtaking us as soon as about 2050, although in some parts of the world the worst may already be unfolding. Check out this video of Tuvalu Foreign Minister Simon Kofe addressing an international climate change conference from knee deep water to illustrate how his low-lying island nation — maximum elevation: 15 feet — is succumbing to rising seas (already, according to Reuters, 40% of the capital is submerged at high tide, and the entire island is expected to be perpetually under water by the end of this century).

To be sure, I laud behavior analysts’ efforts to draw attention to climate issues and to promote sustainable practices that might prevent climate catastrophe. However…

In A Darwinian Survival Guide, Brooks and Agosta make the sobering point that exhortations to save the world carry two limitations. First, they tend to be pretty nonselective, by which I mean they seek to extend a status quo that includes many things worth saving but also practices and institutions that put the world in peril in the first place. That problem deserves serious consideration, but the topic of present interest is that, second, sustainability efforts may distract attention from the need for contingency plans that address what comes next should the “saving” fail.

To be sure, confronting the “end of the world” is a high-powered bummer, but it offers one liberating luxury: If your focus is on what happens after a collapse, you can be picky about what you try to preserve and rebuild.

To be sure, confronting the “end of the world” is a high-powered bummer, but it offers one liberating luxury: If your focus is on what happens after a collapse, you can be picky about what you try to preserve and rebuild.

As far as I’m aware, behavior analysts have held no substantive discussions of what follows from civilization collapse, but one thing is obvious: Just as human behavior got us into the present pickle, it will dictate what kind world human survivors of collapse will inhabit. In this respect, A Darwinian Survival Guide explores a theme popularized by Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series of novels, in which a scholar, recognizing that his civilization is doomed, attempts to set forces into motion that will shorten the long climb back from catastrophe and, hopefully, result in the building of a better world than the one that is soon to pass.

For an interesting (if somewhat rambling) introduction to some of Survival Guide‘s perspective, check out an interview with author Daniel Brooks. From the interview:

What’s important is what happens in the first generation after 2050….That first generation after 2050 is going to determine whether or not technological humanity reemerges from an eclipse, or whether Homo sapiens becomes just another marginal primate species… What we want to do [is] want to tip the odds in our favor a little bit. We want to increase the odds that we’re going to be one of those lucky species that survives. And we know enough to be able to do that. We know now enough about evolution to be able to alter our behavior in a way that’s going to increase the odds that we’ll survive. So the question is, are we going to do that?

As you read Brooks’ comments, consider: Behavior analysts have invested a fair amount of intellectual capital in promoting sustainability… But what is our role if the only agenda left to humanity is to survive and rebuild? The premise of Foundation is that this agenda defines a problem in behavior.

If we cannot save the world, perhaps we can act now to smooth out the path to creating a new one (see Postscript 4). So, chew on this thought. For the sake of argument let’s accept that, no matter what we do now, the seas are going to rise and crops are going to fail and overpopulation is going to accelerate and social infrastructure is going to crumble (and so forth). What kind of behavior change, implemented now, would prepare those who come out the other side of this crisis to survive and, eventually, thrive? How could the needed behaviors be shaped and maintained now, long before they will ever bump into the ultimate contingencies of selection?

To me, this sounds like a job for metacontingencies, something about which behavior analysts talk a lot. I’d love to hear someone with a better understanding of the concept than mine discuss how to engineer practices whose natural consequences will be contacted at the end of a long chain of contextual dominos — basically, after the world enters full-blown crisis and contemporary contingencies no longer prevail.

As the Survival Guide notes, one thing seems clear (again from the interview):

Our governance systems, long ago coopted as instruments for amplified personal power, have become nearly useless, at all levels from the United Nations to the local city council. Institutions established during 450 generations of unresolvable conflict cannot facilitate change because they are designed to be agents of social control, maintaining what philosopher John Rawls called ‘the goal of the well-ordered society.’ They were not founded with global climate change, the economics of wellbeing, or conflict resolution in mind.

In other words, in establishing the metacontingencies of survival, don’t expect any help from big societal institutions (see Postscript 5). The behavior change of today that will save our species tomorrow will have to be insinuated into society less formally than via legislation and regulation. Once more from the interview:

The worst thing you could do to try to create social change for survival [is] to attack social institutions… The way to cope with social institutions that [are] non-functional, or perhaps even antithetical to long-term survival, [is] to ignore them and go around them.

This means culture change — and this is the part that most worries me, because we behavior analysts have not really distinguished ourselves when it comes to redefining culture. We talk a lot about practices that can be beneficial, but have rarely found ways (so far) to get people to adopt those practices at scale.

A Darwinian Survival Guide is interesting food for thought. No doubt if you’re still focused on chasing sustainability rather than programming for survival you’ll find its message inherently depressing. But the realist in me thinks we’d better hedge our bets and expand the way we think about the role of behavior in humanity’s future. As difficult as it has been to forge sustainable behavior to avert catastrophe, it’s even more challenging to imagine how to build behavior that will make humans resilient and constructive when, and after, catastrophe comes.

Postscripts

(1) Behavior Development Solutions offers an interesting-looking continuing education course called, “Behavior Change for Climate Action 101 for Behavior Analysts.” Its purpose: To provide “an understanding of the influencing factors affecting pro-climate behavior; behavior tools for countering these factors; the process for applying behavioral principles to climate change; how to match the behavior tool to the audience and situation; and outreach and communication tips.” All of which is fantastic assuming that climate perturbation is not already past the point of no return. When Jonathan Kimball graciously vetted a draft of this post, he pointed out that, no matter how dire the climate situation seems, it makes sense to behave as if we can still have a positive impact. That is, even if the odds are long we still have to try to save the world. I am certainly not arguing against that.

(2) Below: Rate of major weather-damage events in the US, in selected years. Grey lines represent years prior to 2011, and the thick black line is a historical average. National Centers for Environmental Information graph reproduced from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/

(3) Check out what counts as an “optimistic” appraisal of the climate situation these days. Yikes.

(4) Here’s a modest, less-than-apocalytic example of what it’s like to deal with unpleasant changes you can’t prevent. In the U.S., it appears that several shifts in tornado season (perhaps driven by climate change) are underway. One change is that tornadoes are increasingly popping up east of what traditionally was called “Tornado Alley.” This means that people in the newly-affected areas must learn how to respond to tornado watches and warnings (these are, unsurprisingly given the intermittent negative-reinforcement schedule involved, often disregarded). Another change is that tornadic events, once isolated occurrences, are increasingly occurring in clusters, with just a few hours or days between storms, so that people accustomed to hunkering down for a short interval may now have to plan for more extended hunkering. Clustering also changes the nature of tornado forecasting and warnings, as well as how people may respond to those. All of this, of course, involves moulding human behavior around circumstances that can’t be controlled — a microcosm of the challenges to be faced during a true apocalypse. However, this limited example only addresses short-term survival (i.e., assuming you dodge the latest tornado, you get to return to normal life). It’s a much bigger thing to try to build behavior that will prove useful after The End Of The World As We Know It.

(5) We have plenty of historical examples to show that when one way of life ends what replaces it is not automatically better. For example, societal disruptions have a tendency to centralize wealth and power in the hands of a few who do not necessarily have everyone else’s best interests at heart. See this previous post for details.

(6) The image at the top of the page is all over the internet and of uncertain provenance. It may have originated with Dick Malott but I can’t verify that.