In 1964, B.F Skinner (writing as F. Galtron Pennywhistle) published an article in the satirical Worm Runner’s Digest entitled, “On the relation between mathematical and statistical competence and significant scientific productivity” (see also Postscript 1). It’s reasonable to wonder how Skinner — who on the basis of published works may not be remembered as a comedic genius, or even someone given to public frivolity — arrived at this exercise, and honestly I don’t know the article’s back story (cf. Postscript 2). The article is, however, part of a long running tradition of injecting parody and satire into scholarly discourse. For early examples in literature, think of Shadwell’s (1626) “The Virtuoso” or Jonathan Swift’s (1729) “Modest Proposal.” Famous science hoaxes like Piltdown Man (and an associated “fossil” of the “earliest cricket bat”) serve much the same purpose.

Many contemporary examples of science humor can be found in the aforementioned Worm Runner’s Digest, which published satirical papers from 1959 to 1979, and a similar publication, Annals of Improbable Research, which has operated since 1995. Journal of Polymorphous Perversity, which specialized in psychology-themed satire, ran from 1984 to 2003. The Journal of Irreproducible Results began in 1955; Wikipedia says it’s still publishing, though I couldn’t verify this. Most recently, the Journal of Astrological Big Data Ecology ramped up in 2020. There’s more good stuff scattered across a variety of serious science journals that aren’t too self-important to wink at themselves now and then (e.g., Postscript 6).

In short, over the years a LOT of scientists have put a LOT of effort into skewering science. (Aside: Although behavior analysis has not yet spawned its own humoro-behavioral science periodical, there is empirical evidence to support the contention that Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis is the discipline’s funniest journal).

It’s easy to look down your nose at something as base as humor (for amplification of this point, see Postscript 3). As Stern (2013) recalled, “Critics [of Worm Runner’s Digest] referred to it pejoratively as a ‘scientific comic book,’ arguing that science is not the place for such sophomoric humor.” Thus, If, like Skinner, frivolity isn’t your go-to gear, you may be asking yourself why so much of the planet’s finest brain power would be channeled into what seems like, well, goofing off. One way to parse the problem is through the lens of general theories of humor (see also Postscripts 4 and 5).

Let’s begin by acknowledging that science is crushingly serious work — our job is to describe how the Universe works, for goodness sake. It’s work that yields unpredictable returns with high personal stakes on the line. Everything that matters in terms of tangible professional gain (job security, funding, status) depends on, not just giving science the old college try, but actually succeeding at coaxing secrets from said Universe.

Oh, and at every step of the way, reviewers, theoretical rivals, and other barbarians are taking hostile swipes at your work and your reputation. In short, something sinister or lugubrious may lurk around every corner. Suffice it to say that the next time you see a researcher with a pinched expression, it’s probably not from constipation (or if it is, that’s a physical side effect of professional stress).

Nerds Need a Laugh

With this as context, consider the Relief Theory of humor, which Wikipedia traces back to Aristotle, who suggested that humor “releases pent-up negative emotions that may have been caused by trauma or tragedy we have experienced.” Morreall (2023) elaborates:

The Relief Theory is an hydraulic explanation in which laughter does in the nervous system what a pressure-relief valve does in a steam boiler… According to John Dewey (1894)… laughter… “marks the ending … of a period of suspense, or expectation.” It is a “sudden relaxation of strain, so far as occurring through the medium of the breathing and vocal apparatus… The laugh is thus a phenomenon of the same general kind as the sigh of relief.”

Other adherents of Relief Theory include John Locke, Herbert Spencer, and Sigmund Freud. Whatever the theory’s origins, any serious practitioner of science can understand the steam boiler analogy. Making experiments behave properly is at least as much work as raising children, although experiments find more ways to get into peril than teenagers. A “pressure-relief valve” comes in quite handy, therefore. As Worm Runner founder James McConnell is reputed to have said, “Anyone who takes himself, or his work, too seriously is in a perilous state of mental health.” And yet, in the quest for chuckles, there is a problem: Science nerds mostly hang around other science nerds, who, let’s face it, tend to be humor-challenged. So if want something done, you better do it yourself, and writing a satirical paper would serve the purpose.

Revenge is Funny

A second major account of humor, Superiority Theory, has roots in Hobbes and Descartes. At its core, Superiority Theory holds that we laugh when “we feel superior to the person who is the target of the joke” (again, Wikipedia). Often implied is the inversion of a social power dynamic. For instance, one of my undergraduate textbooks, about the rise of a distinctly American brand of humor after the creation of the United States, noted that a trope of early American fiction involved a high-born Brit finding misfortune at the hands of some putatively simpleminded Yankee hayseed. Apparently it’s funny when the mighty fall.

In science, the “mighty” include those aforementioned reviewers, theoretical rivals, and others who can dent your career, so it makes sense to poke fun at the established science they stand for. Skinner’s well-known feelings about statistics, as expressed in the Worm Runner’s Digest paper, are a likely example of this.

Strategic Play as Simulation

Relief Theory and Superiority Theory both focus on the functions of humor: From these perspectives, a scientist who can laugh is better off for it, at least emotionally. But if we view humor more generally as a form of play, additional possible benefits come into focus. Consider this example of scientific play. Before heading home from the lab each weekend, Alexander Fleming would “paint” petri dishes with various kinds of microorganisms, for example, in an attempt to recreate famous paintings once the organisms bloomed. As Root-Bernstein (1988) has observed, for Fleming this was both a fun game and extended practice with observing the growth patterns of and interactions between various organisms, with the latter proving useful when Pasteur later tackled complex biological problems outside the lab.

In order to prepare his dishes, Fleming had to draw on what he knew but also imagine what might follow from that under conditions that would not occur naturally. By embedding what he knew in a novel context (trying to reproduce famous paintings that presumably had never before been rendered in petri dishes), he exercised existing knowledge networks (stimulus relations), to be sure, but probably evoked emergent relations that were further updated each Monday when he saw what had actually grown.

With this in mind, consider Morreall’s (2023) account of humor as a form of play:

Ethologists… point out that in play activities, young animals learn important skills they will need later on. Young lions, for example, play by going through actions that will be part of hunting. Humans have hunted with rocks and spears for tens of thousands of years, and so boys often play by throwing projectiles at targets. Marek Spinka (2001) observes that in playing, young animals move in exaggerated ways. Young monkeys leap not just from branch to branch, but from trees into rivers. Children not only run, but skip and do cartwheels. Spinka suggests that in play young animals are testing the limits of their speed, balance, and coordination. In doing so, they learn to cope with unexpected situations such as being chased by a new kind of predator.

This account of the value of play in children and young animals does not automatically explain why humor is important to adult humans, but for us as for children and young animals, the play activities that seem the most fun are those in which we exercise our abilities in unusual and extreme ways, yet in a safe setting. Sports is an example. So is humor.

The key phrases in this account are “in exaggerated ways” and “testing the limits.” We know that repertoires become flexible and creative when rich networks of stimulus relations are nurtured. An advantage of operating in an “unreal” context is that the safety can come off, allowing ideas to be tried out that might have no convenient place in the everyday practice of one’s craft. This freedom to leap with abandon into the unknown may be especially valuable in science, which in real life tends to advance at a glacial pace and to be fairly averse to deviations from the status quo. Thus, creating science humor may afford the opportunity to exercise a level of conceptual agility that rarely can be practiced in the trenches of normal science.

To be sure, the conceit of a science joke rests on a foundation of verisimilitude. Often, familiar jargon, methods, and principles lure the reader into a false sense of security before some contrafactual detail sends the narrative careening into uncharted territory. To illustrate the notion of a contrafactual detail, a narrative deflection point, if you will, assume that the principles of behavior as we know them hold, with the minor exception that they follow deceased individuals into the Great Beyond. Knowing that social contact can be a reinforcer, what kind of experiment might result if you hypothesized that ghost appearances in the corporeal world are reinforced by encountering the living? Obviously this is an experiment that wouldn’t be conducted, shouldn’t be, but you get the idea, I hope, that once a preposterous question is posed, to generate an answer within the constraints of real science, well, you have to actually think.

Executed well, this process can prove entertaining for a reader, but my interest is in how it serves the writer, which below I’ll discuss in terms of using contrafactual thinking with students.

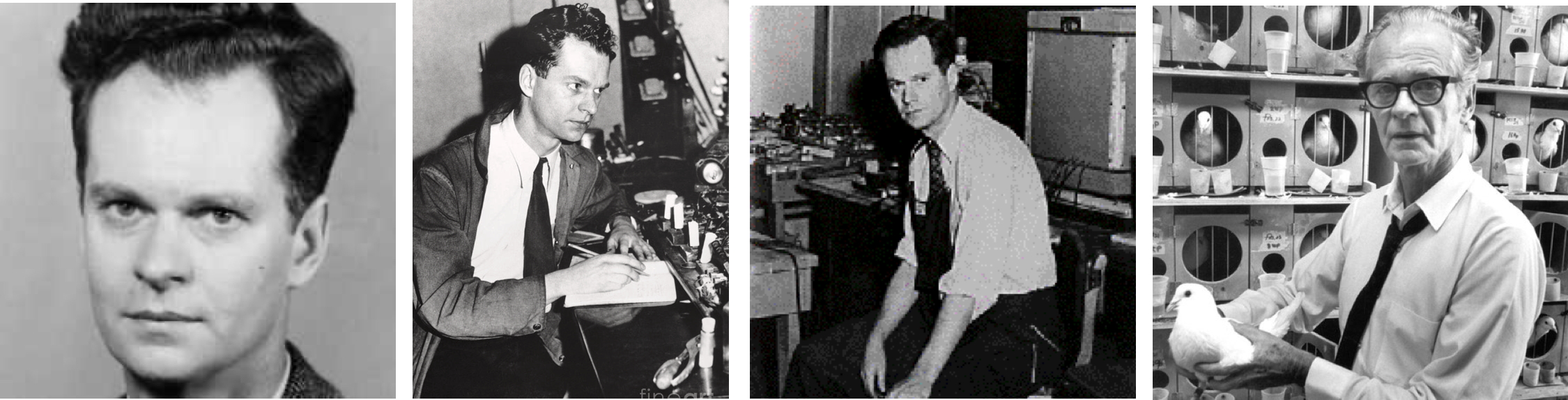

Jurassic World and Zombieland: Enticing Students Into Unreality

Although bogus science papers strive for laughs, the result of contrafactual thinking needn’t be humorous to be useful. In my undergraduate learning principles course, I used to emphasize that operant and respondent learning are highly conserved in an evolutionary sense (they probably arose early in the history of life and hence exist in a vast array of creatures that are related only distantly). Moreover, these processes tend to be preserved in the face of considerable organismic insult (injury, physical illness, psychopathology, etc.). With these premises established, for a final assignment, students were asked to craft a functional analysis and treatment or training plan for an “impossible” creature, i.e., one that has not been studied before and that they will never actually encounter. Two of the options: dinosaurs (extinct) and zombies (fictional).

Long story short, even the less talented students succeeded, to some degree, in showing how familiar ideas could be applied in decidedly unfamiliar circumstances, with the oddest of their conclusions representing preposterous exceptions to everyday experience that, in essence, prove the rules of behavior. For example, one student decided to use errorless discrimination training to teach zombies to approach (and eat) death-row inmates but not other humans. Bizarre and objectionable, yeah, but I’m pretty sure it could have worked.

By the way, a number of former students have told me that, while they had zero interest in autism or organizational behavior management, and instantly forgot that stuff, they absolutely remembered how to determine a zombie’s reinforcers or how to improve on the ludicrous portrayal of clicker training in the “Jurassic World” films. There are, however, limits to what an undergraduate student can accomplish with an exercise like this, because the richness of a simulated reality depends on the depth of your knowledge and the robustness of your relational repertoire. Graduate students would make better guinea pigs, er, participants, so, sticking with the theme of using bogus science to stimulate imaginations about behavior principles, and returning to the theme of satirical articles, here’s an assignment with which I sincerely wish had graduate students to torment, er, enlighten.

Assignment Part 1: Each student creates a satirical or bogus-in-some-other-way journal article. Assignment instructions can be adapted from the author instructions of any tongue-in-cheek journal. Once a topic has been decided upon, key steps include “world-building” with credible science and selecting a point of departure from the real world of science reports. Here’s a simple example to illustrate the steps. Baker (2002, “The sleep retardant effects of my ex-girlfriend,” from Annals of Improbable Research) opened with this milquetoast salvo (modified slightly to reflect APA Style):

The importance of a good night’s sleep cannot be overestimated. Getting more than 7 hours of sleep a night helps in retention and deep encoding of information, which is essential to good school performance (Justice & Bean, 1977). Getting sufficient sleep also elevates mood and enhances happiness (Floyd, 1991).

Clearly this will be a study about factors that influence sleep… but you quickly discover it’s far from “normal science.”

In light of these findings, I conducted a study on factors that influenced the amount of sleep I was getting, in order to determine how to get more sleep. One factor that I predicted would have especially large effects was my girlfriend at the time, Hermina. I have induced that several of my acquaintances believe that Hermina would have significant positive effects on sleep — in the words of one such acquaintance…, “Man, she’s hot. I’d really like to sleep with her” (personal communication, October 19, 2001). Other acquaintances have also expressed an interest in her sleep-inducing properties.

Okay, so this maybe a lightweight example, but the basic idea holds: Goofy science is only fun in a context defined by credible science. Students will find that you have to be really smart about your science in order to get creatively stupid with it.

Once the study has been conceived, it requires results and a Discussion section that also palatably blend normal and stupid science. For an example of deriving the foolish from the mundane, see the excerpt from Adams (2010) at the end of this post.

Assignment Part 2: After the papers have been completed (this will take a while!) and formatted for journal submission (something that can always use more practice), the students can serve as peer reviewers on each others’ papers. This role is traditional with one exception: They are not allowed to challenge the pivot point that leads from normal to numskull science. But they do have to make sure that the real science is portrayed completely and accurately and that whatever happens in the paper flows logically from it, in light of the off-kilter pivot point, of course. In other words, they must vet all of the component stimulus relations and then conduct a “what if” exercise that goes beyond what normal experience would provide. This part of the assignment amounts to tracing another person’s relational repertoire, and I guarantee that it will be both challenging and memorable.

Conclusion

What I’ve tried to convey in this post is that silliness — the scientific type, not the pie-in-your-face type — can demand serious thinking from a creating speaker/writer and promote the same in a listener/reader.

To understand why something is funny, or at least illogical, you have to know quite a bit about how the Universe actually works. Moreover, to create something that’s elaborately funny or illogical, you have to follow a logic that’s simultaneously grounded in real scientific method and principles and deflected by some absurdity into contrafactual territory. And you are obligated to follow that train of logic to its preposterous conclusion, always, along the way, keeping track of what’s bona fide and what’s bogus. In some respects, this is a higher level of thinking than what is often required in “real” science.

Overall, there is an under-appreciated role for “play” in science and science education (seriously, if it was good enough for Pasteur and Skinner…; also see Postscript 7). I urge you, at the least, to check out some of the sizable storehouse of satirical science that’s out there (fortunately for your relational repertoires, there are quite a few papers that, while not behavior analytic per se, address behavior in some way). This will be hit or miss reading, to be sure, in part because some efforts are not well executed and others incorporate in-group whimsy that may sail over your head (my personal Achilles heel is equation humor). But when the right preposterousness meets the right reader, the result can fuel conceptual growth.

An even better exercise, of course, is to author your own silly science. This may be less dignified than reproducing masterpieces in a petri dish, but the conceptual heavy lifting is the same in both cases. And, if enough of you take up the challenge, maybe we’ll finally get that Journal of Humoro-Behavioral Science that our field so desperately needs.

Example of Deriving Nonsense from Mundane-Looking Science

Adams (2010, “The dead grandmother/exam syndrome,” in Annals of Improbable Research) investigated the tendency for college students to report the passing of family members in the interval just preceding an exam. Adams described collecting data on such reports across 20 years of teaching.

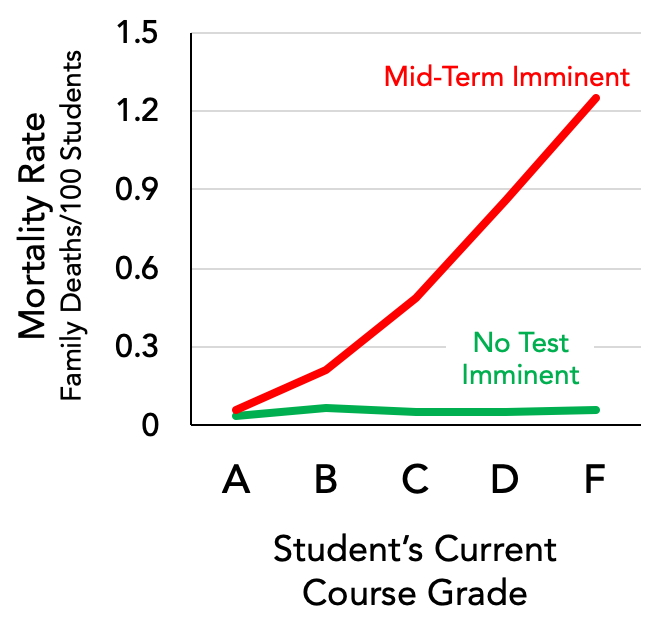

The primary (fabricated) finding was an interaction between student course grade and the presence/absence of an upcoming exam (inset, based on Table 1 of the original article). In these data Adams correctly perceived a correlation between exam onset and student reports of family deaths (mediated by student academic standing), and of course inferred that:

Only one conclusion can be drawn from these data. Family members literally worry themselves to death over the outcome of their relatives’ performance on each exam. Naturally, the worse the student’s record is, and the more important the exam, the more the family worries; and it is the ensuing tension that presumably causes premature death.

Moreover, on the basis of cross-sectional data (again, fabricated) Adams observed that mortality in college students’ family members:

Is climbing at an accelerating rate [such that] 100 years from now [it] will stand at 644/100 students/exam. At that rate only the largest families would survive even the first semester of a student’s college career. Clearly something will have to be done to reverse this trend before the entire country is depopulated.

Adams’ entirely logical proposals to protect the U.S. population: (1) Stop giving exams; (2) Have students lie to their families (“Students must never let any of their family members know they are at university…. Students must explain their long absences by pretending they are in the armed forces, have joined some religious cult, or have been kidnapped by extraterrestrials. All of these alternate explanations will keep the family ignorant of the true, dangerous, fact.”); and (3) Allow only orphans to enroll at universities (“This is an attractive idea, except for the shortage of orphans. More could be created, of course, but this would replicate the very problem we are trying to avoid, i.e., excessive family deaths.”)

Postscripts

- According to the Skinner Foundation, B.F., writing as “Professor Skinnybox,” contributed a second paper to Worm Runner’s Digest, “A Christmas Caramel, or A Plum from the Hasty Pudding.” (1963, Volume 5, Issue 2, pp. 42-46). And there are other Worm Runner papers of potential interest to the present audience, like, “Operant Conditioning in the Domestic Darning Needle (Spina ferrica).” Unfortunately, with the journal now out of print, copies of relevant papers can be hard to find. Selected Worm Runner papers can, however, be found in the anthologies The Worm Re-turns and Science, Sex, and Sacred Cows. A bit of internet sleuthing might be required to track these volumes down.

- Robert Epstein [1997] described the 1964 “Galtron Pennywhistle” paper as an outlet for the same disdain of formal methods that Skinner (1956) expressed, also with a dose of whimsy, in “Case History in Scientific Method.”

- Laughter has been generally scorned by serious thinkers in Western Culture. This may be due in part to the fact that in the Christian Bible laughter is usually malicious, whether issuing from God (e.g., Psalm 2:2-5) or people (2 Kings 2:23). Many important Christian writers have cautioned that laughter is both unkind to others and damaging to the self, in the latter case particularly by undermining that most valued of Christian virtues, self-control. King of the Sourpusses may be Puritan William Prynne, who in 1633 penned an 1100-page screed decrying works of humor as “sinfull, heathenish, lewde, ungodly spectacles, and most pernicious corruptions; condemned in all ages, as intolerable mischiefes to churches, to republickes, to the manners, mindes, and soules of men” (Morreall, 2023).

- For a behavioral account of humor, see “A Threshold Theory of the Humor Response,” by Robert Epstein and Veronica Joker (2007). I like this paper. It’s well-written and scholarly, and it can be readily integrated with behavioral perspectives on the general process of narrative (e.g., see here and here and here). A shortcoming for present purposes, however, is that the paper focuses primarily on listener effects and not on the conceptual benefits to speakers of composing humor.

- Skinner (1957) wrote that, “There are many reasons why men laugh,” (an observation that presumably generalizes to all people, gendered and otherwise). Because there’s no single variety of funny, I doubt that any existing theory accounts for all of them.

- No discussion of science humor would be complete without noting that a joke report is our discipline’s #1 article of all time in terms of dissemination impact (Altmetric attention score >4500, which is close to 10x higher than for the nearest competitor). That fact is a set-up to many punch lines which I’ll leave to your imagination.

- Still think science humor is not worth your time? Then your britches must be bigger than those of Andy Lattal — one of our era’s most serious and accomplished scientists — who spent several years studying a single one-panel cartoon about operant behavior. I am not making this up. Nor am I making up this very serious blog post of Andy’s explaining the strange link between Worm Runner’s Digest and the Unabomber (thanks to Nick Burkey for alterting me to this).