Guest Blog: Denise Ross, Ph.D.

Kennesaw State University

Denise E. Ross, PhD., BCBA-D, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Inclusive Education at Kennesaw State University. She is a certified special education teacher and a former elementary school principal who has established more than 20 professional development partnerships with school districts in Wisconsin, New York, Chicago, South Florida, and Michigan. She conducts community-engaged research focused on the development and dissemination of effective language and literacy instruction for children with and without disabilities. She is co-author of the book Verbal Behavior Analysis: Inducing and Expanding New Verbal Capabilities in Children with Language Delays (Greer & Ross, 2008, Pearson) and an associate editor of the journal Behavior and Social Issues (BSI) where she is currently guest editing a special issue on literacy as social justice (forthcoming in Spring 2024). Ross is also co-editor of When Text Speaks: Learning to Read & Reading to Learn, a book that describes the applications of the science of behavior to literacy (Ross & Greer, in-press, Sloan Publishing). She is a graduate of Spelman College and Columbia University.

Denise E. Ross, PhD., BCBA-D, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Inclusive Education at Kennesaw State University. She is a certified special education teacher and a former elementary school principal who has established more than 20 professional development partnerships with school districts in Wisconsin, New York, Chicago, South Florida, and Michigan. She conducts community-engaged research focused on the development and dissemination of effective language and literacy instruction for children with and without disabilities. She is co-author of the book Verbal Behavior Analysis: Inducing and Expanding New Verbal Capabilities in Children with Language Delays (Greer & Ross, 2008, Pearson) and an associate editor of the journal Behavior and Social Issues (BSI) where she is currently guest editing a special issue on literacy as social justice (forthcoming in Spring 2024). Ross is also co-editor of When Text Speaks: Learning to Read & Reading to Learn, a book that describes the applications of the science of behavior to literacy (Ross & Greer, in-press, Sloan Publishing). She is a graduate of Spelman College and Columbia University.

Did you know that in the United States approximately 30% of all children under age 18 live in economically disadvantaged households? They are children with and without disabilities, from varied cultures and racial/ethnic groups, living in both rural and urban settings, and children who are English Language Learners. Among the many challenges they face, such as food insecurity and inadequate healthcare, their reading outcomes are significantly impacted. In fact, national reports indicate that only 2 of 10 economically disadvantaged fourth-graders read proficiently. The consequences are profound. Economically disadvantaged third graders who do not read proficiently are six times more likely to drop out of school than those who do, leading to potentially long-term detrimental effects on their health, economic, and social outcomes. This issue extends beyond individual lives, affecting communities and the nation as a whole. In fact, the World Literacy foundation estimates that low literacy costs the United States an estimated $300.8 billion in employment, business growth, health, crime, and welfare. The cost of low literacy underscores the importance of effective reading instruction.

When Skinner described textual behavior in his theory of verbal behavior, he may not have envisioned the challenges faced by today’s economically disadvantaged learners. However, his insights into reading remain relevant when addressing the current literacy problem. Research and practice in reading instruction, grounded in the science of behavior and verbal behavior, offer promising approaches to improve reading outcomes. These methods are especially crucial for children who rely heavily on school systems for effective reading instruction. In this blog, I will delve into how the science of behavior and verbal behavior can impact reading instruction. I will illustrate how findings from our field can be practically applied in educational settings, offering concrete strategies to improve reading outcomes. Additionally, I will explore the role of behavior analysts in advocating for literacy, framing it as a vital aspect of social justice.

Contributions of the Science of Behavior and Verbal Behavior to Reading Instruction

Skinner’s verbal behavior emphasized function rather than the form of language. His theory included textual responding, which refers to a reader’s responses to print stimuli. He expanded his description to encompass understanding of text, dictation, transcription, writing, and self-editing, viewing these as behaviors maintained by specific controlling stimuli and reinforcement. He also likened reading to listening and speaking to writing. Since his book’s publication, behavior analysts have continuously contributed to reading research and practice, informed by the broader science of behavior and verbal behavior. A few contributions are described below:

A Strategic Science of Teaching1

Our field uses a science-based approach to teaching that produces desired outcomes for children and adults. When applied to reading, this approach may help produce better outcomes through effective reading instruction. For example, the strategic science of teaching (SST) integrates scientific tools and analytical methods directly into daily teaching practices. Most importantly, in SST, teaching is only complete when a student learns1 . The list below illustrates how SST is applied to reading instruction2:

- Establish a positive classroom.

- Identify and select appropriate instructional standards.

- Convert standards into operationalized instructional objectives and goals.

Operationalized Common Core Reading Standard

| Common Core Standard CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.4.1: Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. | Operationalized StandardGiven a third-grade realistic fiction passage, the student will retell the passage, state two inferences, and give one supporting example or detail from the text for each inference with 90% accuracy across two passages. |

- Assess students’ reading repertoires based on operationalized standards.

- Teach necessary repertoires using instructional demonstration learn units.

- Collect data on correct and incorrect responding during instruction.

- During instruction, make data-based decisions to move forward or intervene based on the learn unit, decision points, and students’ attainment of mastery criterion .

- Repeat steps 3-7 until the instructional standard is achieved.

Protocols for Teaching Reading

The science of behavior has also identified protocols and sequences to teach both early and advanced reading. These include: 1) research-based published curricula and programs such as Direct Instruction Reading and 2) science-based systems of instruction such as the Morningside Academy Reading Curriculum and CABAS/AIL, which have contributed effective approaches to teaching reading. However, when use of behavioral reading curricula is not feasible, there are science-based protocols that can be used. For instance, teachers can embed learn units into a school’s existing reading curriculum. Teachers can also can follow a reading sequence such as the one below, ensuring that the following repertoires are present3:

- Books and texts currently function as conditioned reinforcers for learners.

- Learners demonstrate incidental bi-directional naming (Inc-BiN).

- Children match similar auditory words and sounds

- Children match words and pictures.

- Children demonstrate the following textual responses to fluency and mastery criterion:

- Letter-sound correspondence (letter “a” makes the /a/ sound)

- Phoneme-grapheme correspondence (c,k,ck make the /k/ sound)

- Blending and segmenting (blending the phonemes c-a-t into the word “cat” and segmenting the word “cat” into the phonemes c-a-t)

- Transparent and non-transparent phonemes (i.e., phonemes and graphemes with point-to-point correspondence such as those in the word cat are transparent; those without point-to-point correspondence such as those in the word fought are non-transparent).

- Textual responses to irregular whole words.

- Children read sentences and short passages with known sounds and words.

Verbal Developmental Cusps

Verbal behavior research suggests that if students continue to struggle with reading comprehension or textual responding despite effective instruction, the absence of relevant verbal developmental cusps, like incidental bidirectional naming, might be the issue. These cusps are pivotal changes in behavior, leading to new listening, speaking, reading, and writing behaviors. Verbal behavior research has also identified a sequence of verbal developmental milestones, useful for categorizing and advancing children’s verbal skills, that includes the following stages: pre-listeners, listeners, speakers, speaker-as-own-listeners, readers, writers, self-editors, and verbal mediation for problem solving.

Explaining Complex Reading Repertoires

One of the challenges in reading instruction is that some reading repertoires, such as reading comprehension or motivation, are not sufficiently operationalized to establish them when they are missing. Verbal behavior research has operationalized some of these repertoires. For instance, faulty stimulus control explains why some students respond incorrectly to similar letters such as b and d. Reading comprehension can be explained in terms of relational frame theory, which offers conceptual accounts of the conditions under which reading comprehension occurs. Reading motivation can be measured by the amount of time children engage with books or text. These repertoires can be subsequently established using procedures such as conditioning books as reinforcers or multiple exemplar instruction.

The Power of Effective Reading Instruction

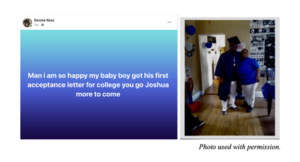

Let me end by sharing a story about Joshua, a second grader in a Title I school where I once worked. When I first met him, he, along with eight other children in his grade, read below the 10th percentile. This group of students was not progressing rapidly enough after the fall semester of instruction. So, in January of that school year, we addressed this issue by starting a special reading group that met for an hour every day. During this extra hour, we modified the school’s reading curriculum by including multiple exemplar instruction across reading, writing, circling, segmenting, and blending phonemes.4. By the end of third grade, Joshua and most of the children in the special reading group had learned to read and, subsequently, passed the state’s required reading test without being held back in school. Years later, I saw the Facebook post below from Joshua’s mom – a powerful reminder of the long-reaching impact that effective reading instruction can have on a child’s life.

The Power of One: Advocating for Economically Disadvantaged Children

The problem of effective reading instruction in this country is a crisis, particularly for economically disadvantaged children who rely on school to correct systemic issues. However, it is also an opportunity for behavior analysts to intervene. By advocating for all children to successfully read, we not only enhance individual educational outcomes but also contribute to broader societal well-being, making this an opportunity for both advocacy and intervention.

So what can we do to help? The word “ONE” forms a good acronym to describe steps we can take to help address the literacy crisis.

- Organize – Find a need in your community related to reading and literacy, and organize your friends and colleagues to teach children to read. If we teach even one child to read, we’ve affected them for a lifetime.

- Noise – How are economically disadvantaged children actually doing in your community? Find out and then make some noise. Write your public officials, speak at public meetings, and advocate for the use of effective instruction for all children but especially economically disadvantaged children in your community.

- Educate -. Read articles, watch videos, attend conferences, obtain CEUs. Educate yourself. Learn how to teach children to read.

Endnotes

1 Greer, R.D., & Ross, D.E. (in press). Introduction to a Strategic Science of Teaching. In Ross, D.E. and Greer, R.D. (in press). When Text Speaks:Learning-to-Read & Reading-to-Learn. Sloan Publishing.

2 Pereira Delgado, J. & Weber, J. (in press). Fundamental teaching practices: From positive classroom management to instructional demonstration learn units. In Ross, D.E. andGreer, R.D. (in press). When Text Speaks:Learning-to-Read & Reading-to-Learn. Sloan Publishing.

3 Mellon, L., & Loomis, K. (in press). Establishing fluent textual responses as a reader and a writer. In Ross, D.E. and Greer, R.D. (in press). When Text Speaks:Learning-to-Read & Reading-to-Learn. Sloan Publishing.

4 Greer, R.D., Lake, K., Savard, M., & Subramanyam, A., (2007). The emergence of novel textual responses and written responses as a function of multiple exemplar instruction across phonemic responses. Unpublished manuscript. Teachers College, Columbia University.