In my advanced verbal behavior class at Western New England University, we like to begin with the most general question one can ask when trying to understand something about the world, namely, “What does it mean to explain something?” Another way of putting it shifts the focus from the speaker to the listener: “What kinds of explanations satisfy listeners so that they go away and stop bothering us?” No doubt there are many answers (see, for example, Holth1), but we tend to settle upon four categories of answers, each with fuzzy boundaries:

1) Unconstrained speculation, unfettered by the scientific status quo. Science doesn’t know everything, so we are free to consider other kinds of explanation for phenomena in nature, particularly in domains where experimental control is difficult to achieve. Many people turn to their horoscopes for explanations, or to palm readers, tarot card readers, crystal-ball gazers, soothsayers, or ancient religious texts. Since adventitious contingencies of reinforcement can be just as effective as reliable ones, we are especially susceptible to the force of coincidence in every form. Superstitions abound, and we subscribe to theories of extrasensory perception and precognition. “Fate” and the kindred concept of “luck” are treated as independent variables, enduring traits, or the intervention by gods or demons. The dice of life do not fall evenly, and many of us tend to think that the dice are loaded. [Cynics snort at the notion that some people are born lucky, but a New Jersey man who won 10 million dollar lottery jackpots on two occasions can be forgiven for thinking he is blessed by a guardian angel. https://www.cnn.com/2023/12/08/us/new-york-lottery-two-time-winner/index.html Another man won two separate million-dollar jackpots on a single night. Likewise, we can sympathize with the countless people who have come within one digit of winning a grand prize and have concluded that fate is taunting them.]

The distinctive feature of such explanations is that they have the linguistic form of an explanation, but no empirical foundation for them beyond what could happen by coincidence. But belief in explanations of this sort is not irrational. We all learn, early in life, to trust the cultural norms of the communities in which we are raised, for it is so often true that the advice of our elders is sound. The important point is not whether such explanations are right or wrong, good or bad, plausible or far-fetched, rational or irrational; rather it is that most people are satisfied by such explanations and look no further. That’s our criterion for what counts as an explanation.

2) A second kind of explanation is rooted in a monistic, scientific worldview. That is, it accepts the status quo of science at the present time, and it addresses remaining mysteries in the language of the sciences. It freely invents explanations for these mysteries but without appeal to mystical or nonmaterial agencies. Theoretical physics is an example, for it wrestles with phenomena at the outer edges of our ability to measure and control. Psychology is rife with explanations of this sort, for psychological phenomena are exceptionally complex, hard to measure, and depend on histories that are difficult to control and often entirely unknown. In effect, the field is playing a game of poker with an invisible opponent in which half of the cards have been painted black and cannot be read. But psychology has been granted two wild cards: evolution and the brain, both of which have impeccable scientific credentials. The mental architecture of much of cognitive psychology and structural linguistics—the mental dictionaries, the encoding and retrieval processes, the assembly line of words to sentences, the language acquisition device, the storehouses where memories are kept and catalogued, the innate rules of grammar—are all charged to the credit cards of evolution and neurophysiology, to be paid off in the future when those sciences mature. Unfortunately, at present, there are no suggestions about how that payment could actually be made. For example, in what sense can a bundle of neurons instantiate a mental dictionary?) Again, the point is not whether such explanations are empty or complete; it is that, for many people, they serve the functions of explanations in allaying curiosity in the domain of interest.

3) The gold standard is explanations that derive from experimental analyses, where all relevant variables can be manipulated or controlled. The validity of such explanations is supported by the successful application of the respective sciences to practical matters. The extraordinary technologies that have arisen from biology, medicine, physics, and chemistry attest to the validity of the principles upon which such technologies rest. In the domain of behavior, experimental analyses have led to general principles that have led to technological applications that justify the claim that we can explain such behavior.

When I was a kid, it was possible to understand most technology in terms of basic processes. With a little training, one could see how an automobile or even an airplane worked. A wiring diagram was sufficient to show how motors and radios worked. A microscope revealed the world of one-celled creatures. Even the newly invented transistor—the size of a lima bean—could be understood, at least in general terms. It was easy to imagine extrapolating to more complex devices. Today, technology has left behind the kid in his driveway with a screwdriver and a soldering gun, but the astonishing power of contemporary science is a testament to the glory of experimental analyses in explaining the mysteries of nature. For most educated adults, accounts that rest upon controlled observation and successful application are taken for granted, so much so that we think of them as truths rather than explanations.

4) But much of nature lies outside the scope of experimental analyses. We have no experimental control over the past, nor of things out of reach, like planets and stars, nor of things too large, like oceans and mountains, nor of covert behavior. In such cases, we deploy Newton’s assumption of uniformity in science, specifically, that the phenomena beyond the reach of an experimental analysis obey the same principles as those within its purview. As Skinner said, in Behaviorism at 50, “When a man tosses a penny into the air, it must be assumed that he tosses the earth beneath him downward. It is quite out of the question to see or measure the effect on the earth, but the effect must be assumed for the sake of a consistent account.”

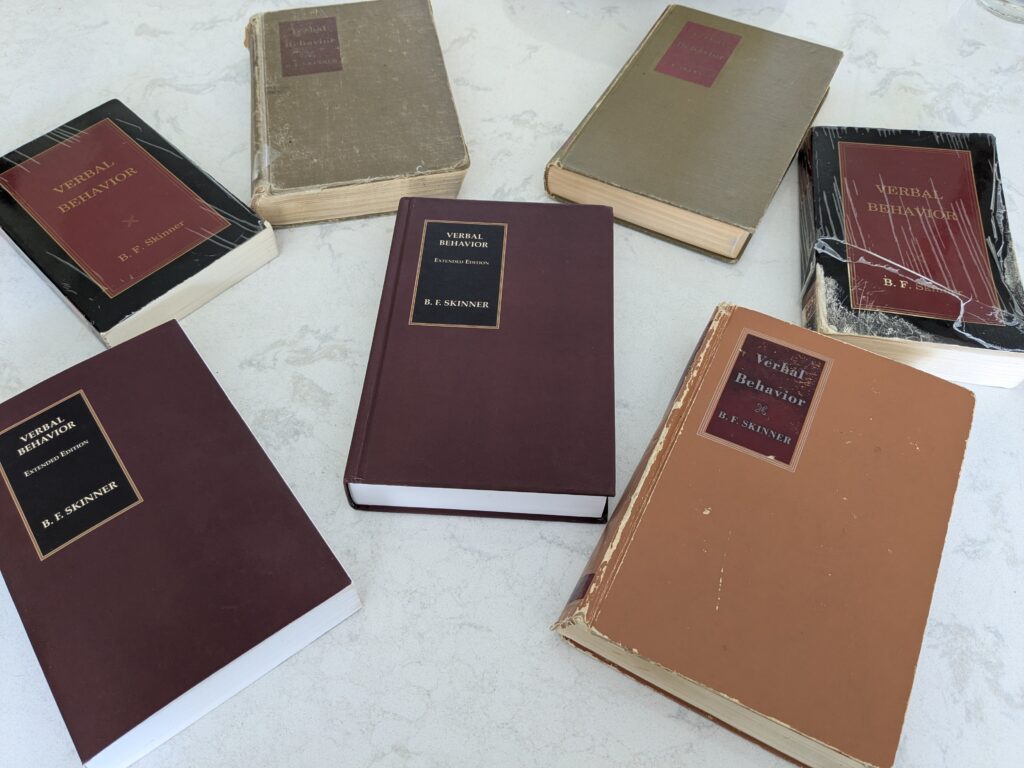

Thus it is that we make sense of natural phenomena, only a small fraction of which have been subjected to an experimental analysis: We make sense of available data in light of established principles that themselves have been derived from an experimental analysis. Thus it is that we understand the evolution of the whale, the astonishing examples of mimicry and camouflage, and every other marvelous feature of the biological world. Our understanding of evolution is almost entirely an interpretation of available data in light of the demonstrable facts of variation and selection in nature. Likewise, we interpret the composition of stars by comparing their light to that emitted by incandescent elements in our earth-bound laboratories. In analogous ways we explain the ocean tides, mountain formation, and continental drift. Finally, it is how we explain, or attempt to explain, complex behavior in natural environments: We turn to principles of behavior that have been derived from controlled studies to domains where experimental control is impossible or impractical. This is the niche of most of behavior analysis: Only a small sample of behavioral phenomena have been subjected to an experimental analysis, but the principles derived from these analyses allow us to make sense of a vast array of examples outside the laboratory. That is, our accounts serve as explanations in that they show that the phenomena of interest obey principles that have been derived from an experimental analysis. This was Skinner’s explicit approach to the extraordinarily complex topic of verbal behavior, and it is helpful to recognize the nature of his enterprise when embarking on a study of his book.

- Holth, P. ( 2014) Different sciences as answers to different “Why” questions. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 14(1), 165-170. ↩︎

There’s one loose end here: Scientists go looking for the kind of “why” evidence they expect will exist. And different sciences or theoretical approaches may pinpoint different kinds of “why” as important. This was Stephen Pepper’s thesis in his “world hypotheses” framework, which says that different theoretical systems have different truth criteria (different kinds of essential evidence). So, if we get to the point of extrapolating to events that can’t be experimentally analyzed, we have taken TWO leaps of faith: we’ve assumed that experimental data have generality to nonexperimental events, and we’ve assumed that certain experimental data are the right data from which to extrapolate. Nothing wrong with except when multiple “why” accounts can be right simultaneously — this might mean events are multiply caused or that they show different kinds of order at different levels of analysis, for instance. And this creates explanatory challenges because of the assumptions that must be made. If Phenomenon A is multiply caused, to what degree is a given instance attributable to Variable X, Variable Y, etc.? If Phenomenon A incorporates different order at different scales of analysis, are we estimating the correct scale when we interpret a particular instance? The only way past these uncertainties is ongoing research after the interpretation. Unfortunately, one adverse consequence of interpretations is that they give the impression of certainty, when in fact what they provide is plausibility. When we feel certain, we cease to ask questions. I think that happened to a large degree after Skinner published Verbal Behavior. We were exceptionally slow to follow the book with systematic research programs. Also, note that verbal behavior is a great example of a domain in which the research we can do is not always experimental. But there are rich corpora of records of language behavior-in-the-wild that relate to phenomena Skinner speculated about. Predictions from Skinner’s account can be tested against these data. Anyway, overall, I hope the above demonstrates that this post stimulated a lot of thinking. Thanks for that!