To get more out of behavior analysis,

we need less Behavior Analysis.

That’s an easy fix.

In the early- and late-1950s, the group of psychologists who had been attracted to the study of operant conditioning found that the journals that seemed most appropriate as outlets for their work were not hospitable toward it. [Those journals] did publish studies by some of the most creative contributors to the new field. But, by and large, few members of their editorial boards had much sympathy toward an approach that stressed the behavior of individual organisms and eschewed formal design and hypothesis testing, both hallmarks of most of the work being published in these journals. By the beginning of 1957, this unhappiness had become so intense that a group met… and decided to start a new journal. This they did, the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (JEAB) first appearing in 1958. Ten years later… they founded a second journal, the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA).

— Laties (1987), p. 495

The thrust of this post is that the period of circa 1958-1968, which we remember fondly for birthing some of our treasured institutions (above), is actually when behavioral psychology began to lose its mojo. Prior to this period, an upstart science had clawed its way from nothingness to relevance (e.g., see Postscript 1). Behaviorism as a general perspective won many converts, and like or hate the science of behavior, no respectable investigator in Psychology could completely ignore behavioral research. Up until this pivotal period, the science of behavior had been a player in the large-scale drama of Psychological investigation.

Beginning with the founding of JEAB and JABA, however, behavior analysis began to retreat to smaller stages. Those who convened to create JEAB (below) had the best of intentions but unwittingly hammered the first of many coffin nails into a movement that was, from Skinner’s earliest conception of it, intended to change Psychology and the world.

The problem: Behavior analysis journals pushed in the opposite direction of Skinner’s original plan. To be sure, those journals were an incubator of ideas, as people who were already sold on behavior analysis now had a convenient way to share ideas and data. But placing articles into publications with limited circulation assured that relatively few eyes would fall upon them (especially in the days before digital sharing).

Perhaps more importantly, this practice insulated authors from having to persuade skeptical outsiders of the value of “an approach that stressed the behavior of individual organisms and eschewed formal design and hypothesis testing.” It’s incredibly informative, in the Laties quote above, that, prior to 1958, mainstream journals “did publish studies by some of the most creative contributors to the new field.” What this shows is that some behavior analysts were cracking the code of persuasion, only to have the motivation for doing so undermined by the availability of JEAB and JABA.

Pearson et al. (2025), Exclusive: the most-cited papers of the twenty-first century. Nature.

Over time, we have created a cornucopia of ways to insulate ourselves from the mainstream.

Following JABA’s founding in 1968, School Applications of Learning Theory (which later became Education & Treatment of Children) launched in 1970. ABAI opened its doors in 1974. Behavior Modification first dropped in 1977. And then we were off to the races, spawning a vast array of journals and entities devoted to behavior analysis. Each of those entities has only drawn our work further from the mainstream, and made us behavior analysts more comfortable with avoiding the challenges of selling a behavioral approach to a skeptical world. And of course left us more lonely. To borrow a phrase from the classics, it is a melancholy object, to those who walk through this great discipline, to see fellow behavior analysts plaintively importuning every passerby for some breadcrumb of approval.

We don’t get a lot of breadcrumbs, as a recent report in Nature helps to illustrate. The table above shows the 10 most-cited science publications of the 21st Century, with citation totals running into the tens and hundreds of thousands.

Now, not long ago I posted a list of the most-cited 21st Century articles in behavior analysis journals. In Postscript 2, I’ve reproduced the list with citation totals updated through April 16, 2025. In comparing my table with Nature‘s, it doesn’t take a mathematical savant to realize that behavior analysis publications tend to generate much less attention than those in many other fields.

Here’s a convenient way to quantify the effect. Below I show the citation totals of the Top 10 most-cited papers (methodological note: see Postscript 3) across all of science (blue), in Psychology (orange), and in behavior analysis (green). Note the logarithmic ordinate.

The most-noticed Psychology papers have been cited more often, by a factor of at least x22, than those in behavior analysis. For papers in science overall, it’s at least x100.

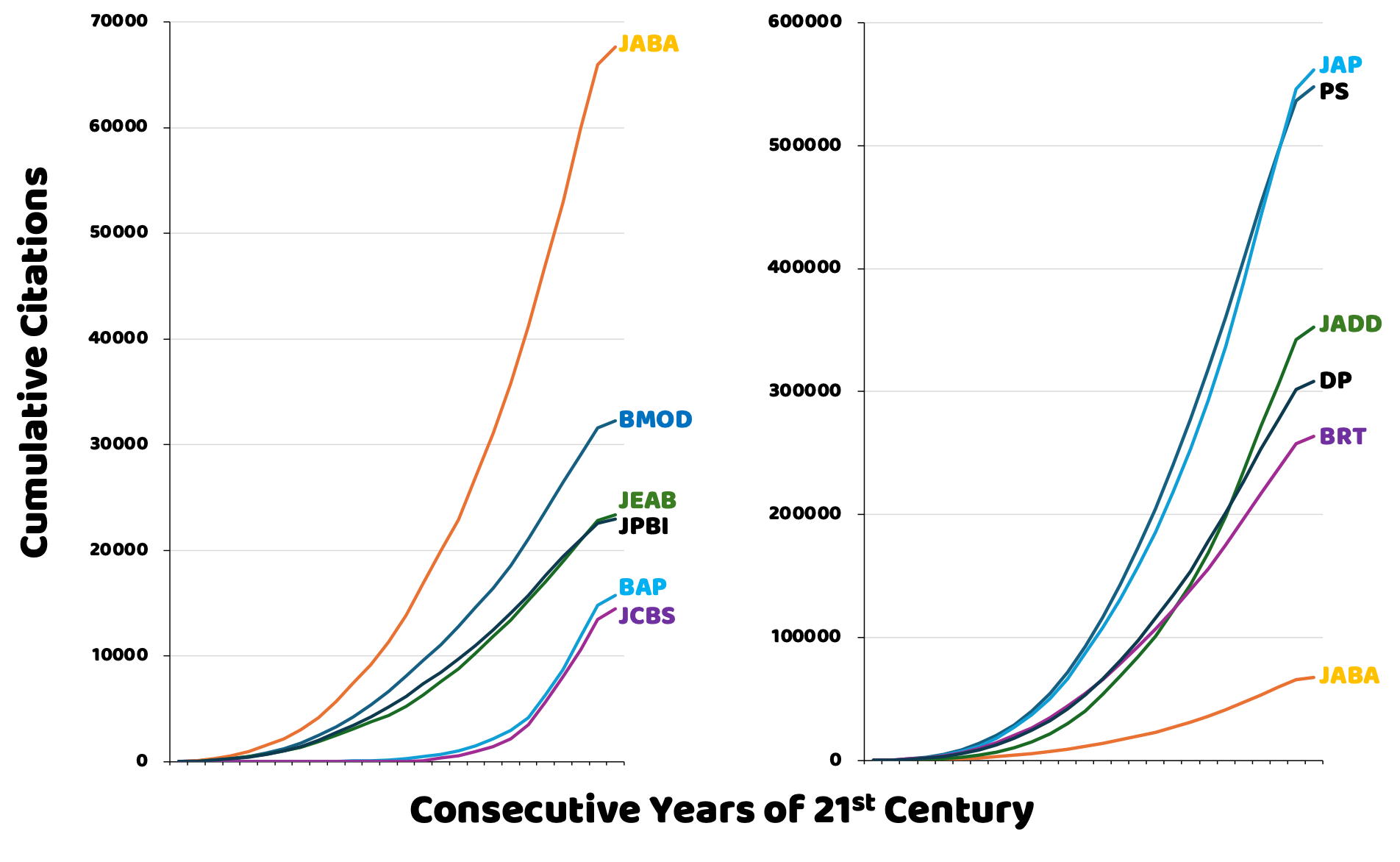

For another comparison, see Postscript 4, whose left side shows the cumulative annual citations of 21st Century articles in several behavior analysis journals, with JABA the clear top performer. The right side compares JABA to several well-known Psychology journals with thematic connections to work work in behavior analysis (I chose these mainstream journals pretty randomly; you could choose your own set and probably get similar results).

In this context, JABA’s scholarly impact seems puny. Consider that in the 21st Century JABA has averaged roughly 2700 citations per year, while Behavior Research & Therapy has tallied over 10,000. For Journal of Applied Psychology, it’s more than double that. Such data show that a LOT of people are interested in science — even psychological science! We just aren’t reaching many of them.

Overall, the conclusion is inescapable: We behavior analysts inhabit an intellectual ghetto, far removed from the shiny streets of mainstream science. Those aren’t my words. They’re the words of B.F. Skinner, who in late career became disillusioned at his failure to remake Psychology, which he concluded was terminally infected with failed ideas. He memorably proclaimed that:

We have been accused of building our own ghetto, of refusing to make contact with other kinds of psychology. Rather than break out of the ghetto, I think we should strengthen its walls.

— Skinner (1993/2014, p. 24)

Strangely (to me at least), Skinner told us that isolation is not just tolerable; it’s noble. Better, he seemed to say, that we refine our craft in isolation than engage with a world that might resist or pollute our approach. The thing is, though, we have never fully bought Skinner’s curious take on this. Yes, we proclaim our proud independence from conventional psychological science, and we create professional structures that keep us separate. But we also frequently, loudly, forlornly bemoan our failures to gain mainstream acceptance. Deep down, we know that a ghetto is not a safe haven but more of a prison.

Skinner often commented on the foibles that make mainstream culture resistant to a science of behavior but, as in the “ghetto” article, he said little about what a science of behavior should do to make itself more palatable to people in the mainstream. I suspect we’ve overlooked this omission because events beginning in the 1950s insulated us from the pressure to become more palatable.

Having turned my thoughts for many years upon this important subject, I submit that there is a simple solution: Reverse the factors that brought us to our present state. Therefore we must immediately dissolve all journals, associations, boards, committees and other institutions devoted to the care and feeding of behavior analysis.

Once the troublesome entities are eliminated, overnight we will have reset the calendar to a better time, circa 1957, when behavior analysts who wished to register the importance of their work had to work for the privilege. Behavior analysts will no longer be able to assume that their papers and posters will, for little more than the price of organizational membership dues, be accepted for presentation at the ABAI conference and other professional meetings. They will no longer be able to grease the wheels of peer review by parroting the obscure verbal practices of previous behavior analysis articles. Nay, if they wish their work to find an audience, they will need to scrape and claw as Skinner did in the earliest days of his research program. They will have to try all sorts of approaches to research design and manuscript construction, but over time selection by consequences will yield a verbal community that knows how to act effectively on that bigger stage.

| Of course, it goes without saying — though I can’t stress this enough — that it’s also essential to eliminate institutions and structures designed to prop up behavior analysis practice. Professional credentialing exists mainly to protect practitioners’ market share and to assure a steady supply of third-party payment — in other words, to insulate practitioners from the contingencies inherent in fair competition with non-behavior-analysts. This eliminates the need for practitioners to be the absolute best they can be, and therefore weakens the discipline. Henceforth, I propose, practitioners will need to obtain a degree that is marketable because consumers recognize and value it (e.g., clinical or counseling psychology, school psychology, etc.), and they will have to outcompete others with the same credentials through competence and effective communication with the public. When practitioners can no longer stay in business simply because their professional niche is legally protected, they will have to grow and innovate in ways that will spur behavior analysis forward. |

You may argue that the simple program I propose could never be implemented, and I agree that substantial challenges are involved. Many individuals derive professional status and identity from the relevant entities, whose dissolution they are sure to resist. But their interests have nothing to do with the conduct and dissemination of our science, and therefore can be safely ignored.

To be sure, once my program is in place, those individuals who once orchestrated behavior analysis journals, associations, boards, committees, and other institutions may struggle at first to rejigger their sense of purpose. They will, however, soon discover time and energy (plus funds once directed to memberships and journal subscriptions) freed up for figuring out how to put the best of behavior analysis before scientists and citizens everywhere. This desirable end justifies any temporarily uncomfortable means. I call on the leaders and constituents of all behavior analysis journals, associations, boards, committees and other institutions to prioritize the common good and take appropriate action in order to assure the survival and well-being of our discipline.

Postscript 1: Most-Cited Behavior Analysis Journals

Not long after its launch, JEAB ranked #117 on a list of 1972’s most-cited journals in all of science. But that didn’t last. Such lists began incorporating more journals, creating stiffer competition, and citation norms shifted as the community of science grew. In the latter case, note that in recent years JEAB’s citation impact factor has remained near what it was in 1972. However, with ever more scientists writing (and citing) ever more papers, impact factors of other journals rose. In 2023, JEAB ranked #4101. Some other behavioral journals: Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science = #1470, JABA = #3216, Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions = #3379, Behavioral Interventions = #7851. And here’s something else to consider. Historically, behavioral journals have had unusually high rates of self-citations, meaning that a lot of a journal’s attention is from its own contributors. The higher the rate of self-citation, the less impact a journal has outside of its core readership.

Postscript 2: 10 Most-Cited Behavior Analysis Articles of the 21st Century

Through April 16, 2025

Postscript 3: Citations of Top-10 Papers

To create my graph of the highest-performing papers in science overall, Psychology, and behavior analysis, I relied exclusively on the Dimensions Citation tool. That means the papers and citation totals for science overall in my graph may be different from those in the Nature table.

Postscript 4: 21st Century Citation Trends

Left panel: Cumulative citation counts for 21st Century articles in 6 behavior analysis journals. Right panel: JABA compared to five well-known Psychology journals. Note the different ordinate scales in the two panels.

Note: BAP began in 2006; JCBS began in 2012.