Skinner (e.g., Science and Human Behavior) understood that, to everyday people, the plausibility of a behavioral perspective depends on its ability to explain simple everyday phenomena — especially those that seem to violate the laws of behavior. Explaining is a valuable exercise for us, too, because the explanation isn’t always simple. Here’s an example.

Pedaling to Infinity

Image credit: leggotrippin

It’s said that once you learn to ride a bike you never forget, and in fact many people who mastered bicycling when young continue to ride into old age. More profoundly, many people effortlessly return to bike riding after shelving it for a long period (prime example: centenarian speed cyclist Robert Marchand; see Postscript 5).

In a world where learning outcomes can be quite fragile, the apparent permanence of bicycling prowess seems like a weird outlier.

So what makes bicycling special?

My first behavior analysis professor, Rob Hawkins (see Postscript 1), taught that if you want to understand a behavior, find out where it does not occur. For clues about bike riding, then, please check out the following video clip, which colorfully shows an instance in which previous cycling experience does NOT help with current riding. You’ll need to watch roughly the first 3 minutes. The third minute is the critical part, showing the dark magic of the audaciously-named “Backwards Brain Bicycle.” The two minutes prior show how this bike is mechanically unusual (though feel free to ignore its inventor’s psychobabble explanation of the design).

Most notably, you will see experienced bike riders looking like complete novices…. Honestly, my four-year-old daughter did better her first time on a regular bike than these lifelong riders do on the “Backwards Brain Bike.” So what gives? How is The World’s Most Durable Behavioral Phenomenon undermined so completely?

Extinction as a procedure occurs when reinforcement of a previously reinforced behavior is discontinued; as a result, the frequency of that behavior decreases in the future (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007).

Engineered Against Extinction

We now have enough to explain why bike riding, in its typical form, is so durable. The performance of interest is a constellation of movements that we can call “bike behaviors” (pressing the pedals to accelerate, adjusting the handlebars to steer, and shifting the body weight to maintain balance; also see Postscript 2). Important consequences of emitting bike behaviors include getting somewhere quickly and avoiding painful crashes.

In the language of behavior analysis, a bicycle and the ambient environment constitute the antecedent stimulus context in which “bike behaviors” contact the aforementioned consequences. The bicycle has been called “the perfect machine” because it so intricately links specific actions to environmental context and consequences. It’s so perfect, in fact, that you can’t much improve on it. As a result, although there are hundreds of commercial bicycle manufacturers, one bicycle uses pretty much the same physics as every other.

And this helps to explain why people rarely “forget” how to ride a bike: Nearly every bicycle works the same way, so antecedent and consequence conditions are constant, no matter when in life you pop yourself onto a bike, no matter how long it’s been since your last ride, and no matter what bike it is.

And that makes you, the rider, a bit like the pigeons in Schwartz and Reilly’s (1985) study, because no matter how much time has passed since your last bike ride…

- The “experiment” (your bike) still works the same way. Thus what you learned in the past still has the same consequences as it always did.

- You don’t experience extinction, which for this behavior would consist of emitting “bike behaviors” but not traveling where you want to go and/or avoiding crashing.

Now, About That “Backwards Brain Bike“

We can now account for the dark magic of the “Backwards Brain Bike,” which changes the physics of a typical bike in one small but catastrophic way: When you turn the handlebars left, the bike turns to the right (and vice versa). What riders have learned on regular bikes no longer applies, and the result is the complete disintegration of skill.

The altered bike looks like a normal one, so in this sense the antecedent stimulus context hasn’t changed. But rider movements that have been intricately tuned to the physics of a regular bike just don’t work now. Because those movements have been richly reinforced in the past, they’re bursting with behavioral momentum, and therefore won’t go quietly into the night. In the video you see riders embodying the definition of insanity — trying the same things over and over, and expecting a better result. Even transparently explaining to a rider how the “Backwards Brain Bike” works is not enough to overcome a very stubborn behavioral history.

Left image credit: hackaday.com. Right image: Screen grab from the video.

In brief, what the “Backwards Brain Bike” does is break the operant called “bicycling.” Familiar discriminative stimuli are paired with unfamiliar behavior-consequence relations, and the whole thing comes crashing down (literally). In the end, the “Backwards Brain Bike” is an exception to one rule (bicycling is forever) that proves another (an operant is, for all practical purposes, forever unless something comes along to break it).

By the way, although the “Backwards Brain Bike” is extremely effective at breaking bicycling, we might expect similar effects, to varying degrees, in at least some of the situations shown below, because all of them mess with the physics of riding in some way.

If Forgetting and Extinction Got Married and Had a Baby

At the start of this post I dismissed the concept of forgetting as irrelevant to bicycle riding. Probably you’re not surprised given that behavior analysts have issues with cognitive concepts of memory. But I wasn’t actually picking a theoretical fight, and in fact there might be a reason to talk about forgetting after all (see Postscript 3). Bear with me here.

Contrary to what everyday people think, memory experts are not persuaded that the passage of time alone ever creates forgetting. Rather, they tend to emphasize interference, in which “forgetting occurs because memories interfere with and disrupt one another.” In other words, memories don’t go away on their own but instead can be crowded out by other memories. The passing of time matters mainly because this affords opportunities for competing memories to be made.

Now, if we gerund memory into the behavior of remembering, this is a lot like how operant behavior works, isn’t it? One key way that operant behaviors go by the wayside is that other behaviors replace them (this is more or less the point of the matching law, and also the bedrock idea behind many applied interventions).

Cognitive scientists would call bicycling skill an example of procedural memory, which, as conventionally explained in cognitive science, is not going to leave a behavior analyst feeling well informed. But if you look at the facts of procedural memory rather than the theory, you’ll see three inviting things. First, procedural memory is “the memory of how to do certain things” (rather than talk about them). This implies what we behavior analysts call behaviors, typically observable movements of the body through time and space. Some examples of procedural memory in action:

- Playing piano

- Skiing

- Ice skating

- Playing baseball

- Swimming

- Driving a car

- Riding a bike (emphasis added)

- Climbing stairs

Second, “procedural memory is generally associated with repetition of a procedure—practice … which strengthens the memory and helps build skills.” Duh. Most behaviors are acquired through ongoing interaction with the environment.

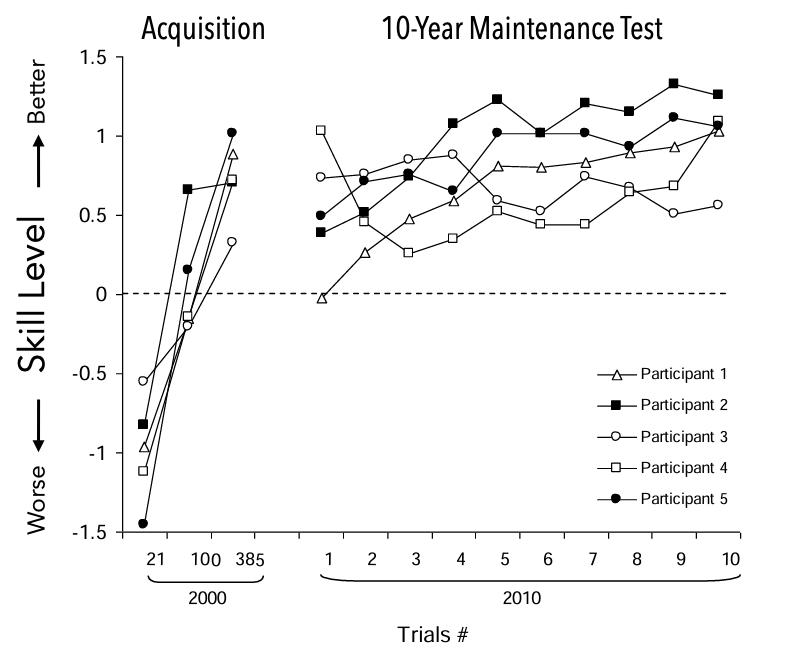

Third, procedural memory is often remarkably resistant to forgetting. Here’s an example. Five people participated in a procedural memory experiment, conducted in 2000, in which they developed skill on a ski simulator through extensive practice. They were tested again 10 years later, after no further experience with the simulator. The left side of the figure below summarizes skill acquisition across 385 practice trials in 2000. The right side shows that performance was basically unchanged when tested again in 2010.

Adapted from Figure 5 of Norrit-Lucas et al. (2013).

I hope the figure reminds you of the Schwartz and Reilly (1985) experiment and the Skinner example mentioned earlier, because we’re probably talking about the same general process. Just as in bicycling, a ski simulator provides highly specific feedback (consequences) for very specific movements in a very specific stimulus context. The passage of time does not change the resulting operant relation, so what’s learned should be essentially permanent, unless something breaks the operant (for instance, imagine that some sadist builds a “Backwards Brain Ski Simulator”).

If you re-check that list of procedural memory examples, above, you’ll see behaviors that are fine-tuned to very specific stimulus contexts. And to the extent that “what works” in each context is pretty invariant — unchanging over time — procedural memory (behavior) should be pretty much unaffected by the passage of time. For example, one doesn’t normally forget how to walk or to write. Only the perturbation of operant relations should interfere with well-learned behavior, which didn’t happen in the ski simulator, but of course happens all the time in real life. For example:

- Many people who can walk just fine on solid ground wobble at their first experience on a treadmill, or become unsteady on the deck of a rocking boat. Similarly, walking in reduced gravity, as per on the moon, is a challenge for people who learned walking in Earth gravity.

- My handwriting isn’t terrible, but the first time I had to write on a board at the front of a classroom, I produced indecipherable scribbles. The gist of the problem: Antecedent-behavior-consequence relations (the “physics of writing”) differ for vertical and horizontal writing surfaces.

See Postscript 4 for more on what it means to break an operant.

Conclusion: Nature Did a Brilliant Job of Designing Learning

More than anything, the “Backwards Brain Bike” highlights the incredible sophistication of the laws of behavior that natural selection provided for us.

There are very specific rules for how to create learning — so specific that when the conditions are right learning must occur (ask any parent who inadvertently reinforces a child’s tantruming). But there are also very specific rules for how to demolish behavior. “Demolition” is necessary because if everything learned was forever, well, I would still crawl and call all four legged mammals dog.

The real genius of learned behaviors is that, metaphorically speaking, they know when to hold together and when to fall apart. More accurately, once learning is created, active experience of a particular sort is required to eliminate it. And accordingly a lot of what we learn in life eventually “stops working” and/or gets replaced with something that works better. But some behaviors, like riding a bike, keep on going and going and going… because they don’t stop working, and nothing else works better in the same context. The “Backwards Brain Bike” is a reminder that this is due to static environmental demands rather than some special feature of the behavior itself.

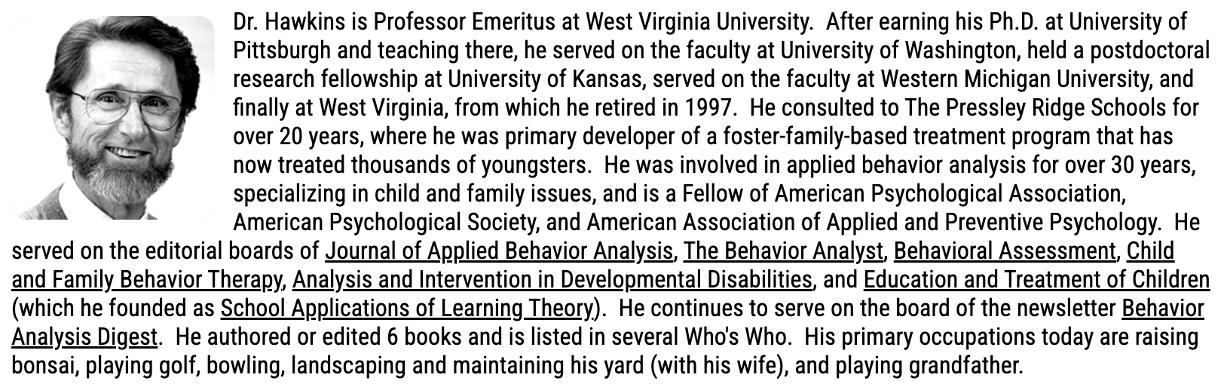

Postscript 1: Rob Hawkins, An Important But Underappreciated Applied Behavior Analyst

Postscript 2: About “Bike Behaviors“

Part of what makes the “Backwards Brain Bicycle” difficult is that the behavioral features of riding normal bike — how you adjust your weight to maintain balance, how you orient to change direction — are pretty similar to what applies to other kinds of movement you’ve been doing your whole life (crawling, walking, running, etc.). The altered bike breaks intuitive rules of physics that we take for granted.

Postscript 3: Another Reason Not to Forget About Memory

I didn’t emphasize this above, but here’s another reason to talk about forgetting: There’s a gigantic literature out there, authored mostly by cognitive types, defining conditions under which memory does and doesn’t hold up. How big? A quick Web of Science search (December 29, 2024) steered me to 1,012,168 published sources with memory as the topic, and only 10,841 for positive reinforcement. Another comparison: 59,873 hits for forgetting and 1526 for operant extinction. In short, there’s vastly more research on memory than on anything in behavior analysis and — whether we like cognitive science or not — if we’re to have a complete science of behavior we must be able to explain all of those data.

Postscript 4: One More Example of “Breaking” (Pun Intended) an Operant

I hope it’s obvious that, when it comes to perturbing operant relations, the boundaries between stimuli, behaviors, and consequences becomes blurred. Here’s an example to illustrate.

As a youngster in Little League Baseball, I was a terror at the plate (i.e., a very good hitter). Until I wasn’t. Up until the age of 11 or so hitting seemed easy. Someone throws the ball. You swing the bat. You hit the ball. Piece of cake. Then one day I was promoted to a higher-level league, and I stepped up to bat against a lanky left-handed pitcher named Ellis Reed. His first pitch was something so incomprehensible to me that I was unable to move my bat. The next one I probably missed by two feet, and the third one sent me back to the bench, a strikeout victim but someone whose days in organized baseball were numbered.

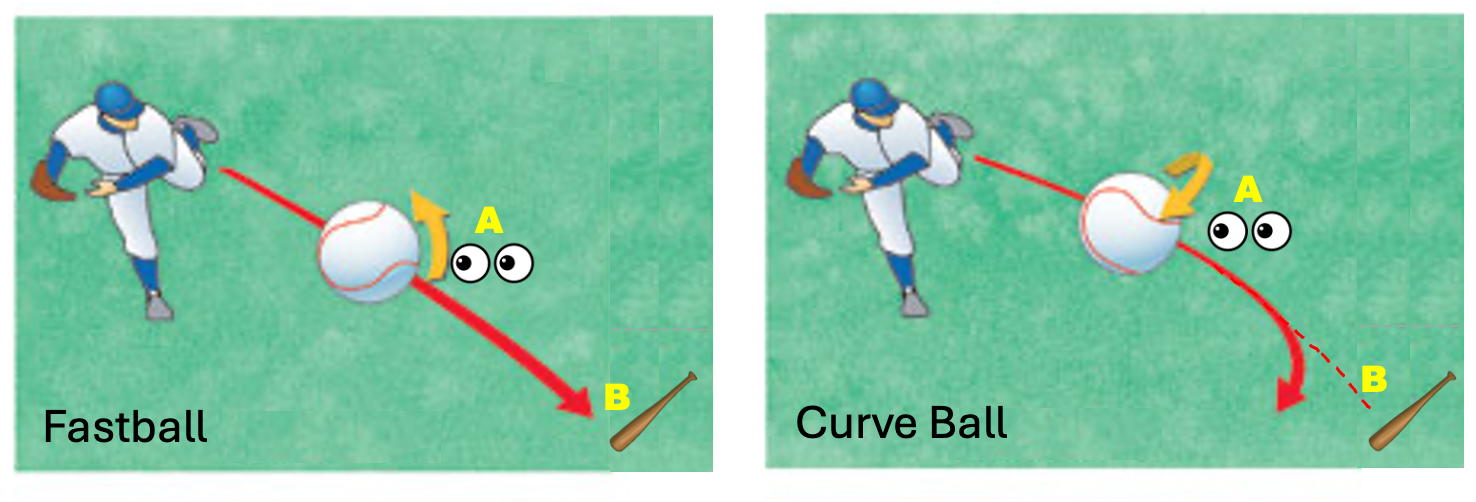

Ellis Reed “broke” batting for me by throwing a curve ball, a pitch with a peculiar spin that causes it to break horizontally. Now, most youth baseball leagues forbid very young pitchers to throw the breaking ball (because it’s rough on the elbow), meaning that until age 11 I’d only seen pitches that traveled in a fairly straight line.

Here’s how a curve ball is different. When batting you have very little time to react to a pitch, so you need to eyeball it at a distance (below, left: Point A) and begin to swing before the ball actually arrives in your vicinity. With a fastball, the ball’s trajectory is roughly linear, so the skill I honed was, in effect, to swing at where the pitch appeared to be heading (below, left: Point B). Unfortunately, with a curve ball what you see early on looks pretty similar to a fastball, but the ball does not arrive where it seemed to be heading. Treat it like a fast ball, and you end up swinging at someplace where the ball isn’t.

Curve balls are hard to hit as a kid not just because up to that point you’ve only seen straighter pitches. Most moving objects in everyday life follow what might be called Newton’s First Law of Motion For Dummies: They end up where they are seem to be heading. I won’t go into technical details here, but curve balls follow the actual First Law. Yet a lifetime of experience tells you that what you see shouldn’t happen.

To be clear, my inability to hit the curve was not a generalization failure: Quite the opposite. Movements that worked just fine with fastballs got occasioned also by curve balls, but with very different consequences. And no matter how much practiced I never did learn to hit the curve. That’s partly a discrimination failure, but also a failure to develop the requisite behaviors, because how you swing to make contact with a curve ball is different from how you swing to clobber a fastball.

In the end, it’s simplest, and most accurate, to say that hitting a fastball and hitting a curve are two different operants involving different combinations of stimuli, responses, and consequences.

Postscript 5: Robert Marchand

Cyclist Robert Marchand was born in 1911 and learned to ride at age 14, after building his own bicycle from scavenged and improvised parts. World War II and the demands of work put a temporary end to his cycling, but finally, in 1978, at age 67 and after a decades-long hiatus, he resumed riding.

No relevant reports are available, but it’s a good bet that upon his first return to the bike Marchand pushed off from the curb, stayed brilliantly upright, and steered that machine exactly where he wanted it to go. He continued to ride outdoors daily, weather permitting, until age 108, when hearing loss made it too risky to share the road with automobiles (a stationary bike had to suffice thereafter). On May 22, 2021, six months before his 110th birthday, Marchand finally rode off into the proverbial sunset, presumably still brilliantly upright.