Deweyan Dogma in Science Education

A thought-provoking article in Aeon magazine suggests that the modern scientific method, or at least how it’s taught, took cues from rather unstructured observations of children at play. Here’s the argument: John Dewey (1910), in his book How We Think, described watching children explore, play, and discover how the world around them works. He thought their process was far from random:

Each instance reveals, more or less clearly, five logically distinct steps: (i) a felt difficulty; (ii) its location and definition; (iii) suggestion of possible solution; (iv) development by reasoning of the bearings of the suggestion; (v) further observation and experiment leading to its acceptance or rejection; that is, the conclusion of belief or disbelief.

Image from Andragogia Brasil.

Some saw in this brief passage an informative distillation of ideas about the process of conducting science that scientists and philosophers had long advanced, though typically via dense and tortured text. Dewey seemed to have cut through all of the troublesome verbiage and honed in on the essential steps: Research question, operational definition of variables, hypothesis, development of method, and observations that bear on the hypothesis (with revisions of such as the data dictate).

Almost immediately, science textbooks began adopting Dewey-esque descriptions of the scientific method… descriptions that continue to dominate science teaching today, not to mention popular explanations of the scientific method.

Now, explaining difficult ideas clearly is a good thing, and most people are happy when their ideas are appreciated and embraced. But Dewey hated his unwitting impact on science education. Why? Three reasons.

First, there’s a distinction between description and prescription:

Dewey wasn’t happy that the steps he outlined grew into the standard representation of scientific method. After all, he hadn’t called his book ‘How Scientists Think’ or ‘How We Should Think’. He had called it How We Think.

Dewey’s writing might have implied a way to learn, but he never said it was the way.

Second, Dewey regarded textbook distillations of the scientific method as suffocatingly rigid. In How We Think, Dewey had emphasized that the learning process involves spontaneity, of freely redirecting one’s attention to things that are interesting. We could as easily speak of curiosity or, to be more behavioral about it, natural reinforcers, i.e., letting the thing you interact with shape your behavior. This is basically Frances Bacon’s “Nature, to be commanded, must be obeyed.” It’s Skinner’s admonition that “When something interesting comes along, follow it.” And, as Skinner would colorfully illustrate in “Case History in Scientific Method,” curiosity demands that you adapt your methods when “something interesting” tells you that is necessary.

Third, Dewey believed that learning — including learning through science — is always embedded in a social milieu, and he was a big believer that the primary purpose of science is to understand and solve social problems. This is akin to the Baer et al. (1968) notion of social significance. As a side note, Dewey lived long enough to see the World War II era emergence of a “pure basic” research that valued squeaky-clean scientific methods and theoretical questions more than ties to practical problems. He must have found that frustrating.

Our Emergent Dogma

It’s funny, in a way, that what exasperated Dewey is that science education ignored the more behavioral aspects of his ideas. Today most behavior analysis wouldn’t call Dewey a kindred spirit, and he was inspiration for play-based therapies and vague approaches to child education of which we might not be fond. If you read Dewey in the original, however, you’ll find a lot that aligns with contextualistic thinking about behavior dynamics (for instance, Dewey was expressly interested in what we call derived stimulus relations). But that’s a topic for another time.

For the moment, I’m focused on the irony that ignoring behavioral notions from the Dewey canon led to the widespread belief that there is just One Scientific Method. Skinner’s “Case History” was an effort to dismantle that belief but — here’s that irony — despite all that’s great about our science, we behavior analysts have at times shown a proclivity for our own brand of dogmatic thinking.

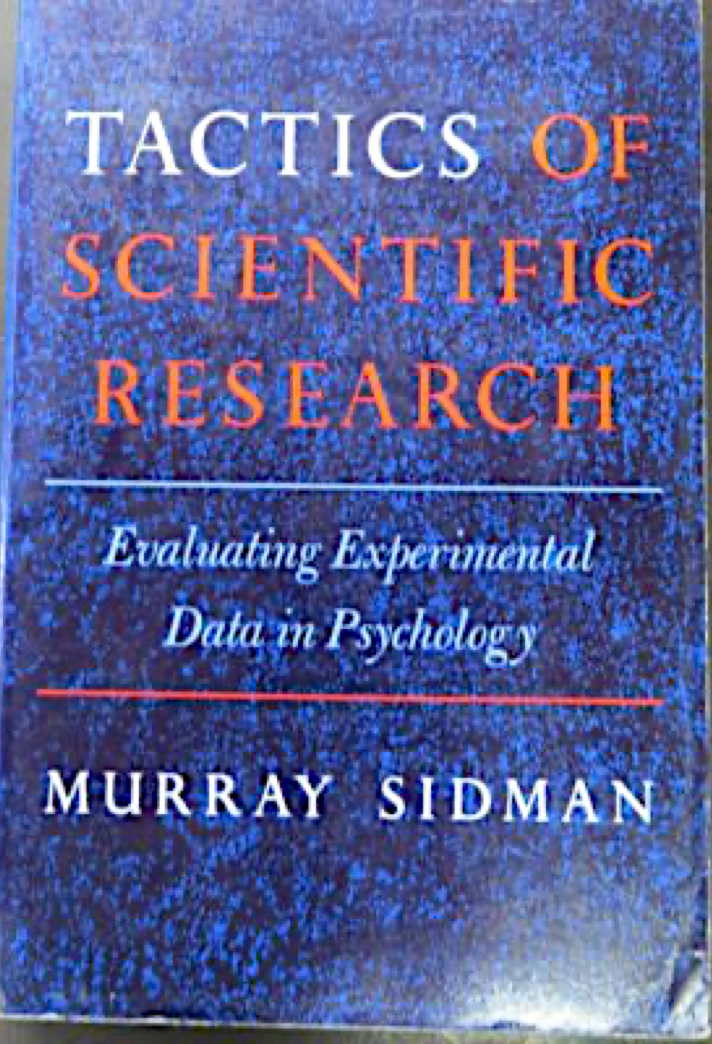

The best example of emergent dogma in behavioral methods might be the free-operant steady-state approach in basic research, an approach that was brilliantly detailed in Murray Sidman’s (1960) Tactics of Scientific Research. Check out whatever studies you can find in the experimental analysis of behavior up to 1960. You’ll see much exploration of momentary effects of schedules of reinforcement (as depicted in cumulative records) and a lot of trials-based studies of stimulus control. In many cases an entire study was one interesting condition, or an A-B manipulation. By 1970 or so, however, all that had changed, with the norm being A-B-A-B designs or variants thereof, and data presented in time-series-style graphs showing response rate across sessions. By 1976, Skinner (in “Farewell My LOVELY!“) had penned an obituary of sorts for the exploratory approach to research he had pioneered. Sidman’s account of a way to do competent research had become perceived as the way.

In fact, the free-operant steady-state approach entrenched itself so quickly, and so thoroughly, that by the time Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968) wrote their “birth announcement” for applied behavior analysis (ABA) — only eight years after Tactics — they felt compelled to explain at some length (and rather derisively, in fact) why reversal designs were a poor fit for exploring questions of social significance.

But dogma is in the eye of the beholder. Eventually certain aspects of the famous Baer et al. “seven dimensions” of ABA became so entrenched that, as Derek Reed and I wrote a few years back, they became perceived as defining the way to do applied research rather than a way (more irony, since a lot of socially significant problems are hard to study within the Baer et al. framework).

The notion that there’s only one right way to do things pops up everywhere, and not just in research. For instance, many applied behavior analysts will remember the controversy that erupted when the methodical, experimental, time-honored approach to functional behavioral assessments, as pioneered by Brian Iwata and colleagues, began to be challenged by briefer assessments that were easier to implement in the field. Iwata-style functional assessment is a superb way to determine behavior function, but some regarded it as the way, and they were none too pleased with the adaptations.

Reinforced Rigidity

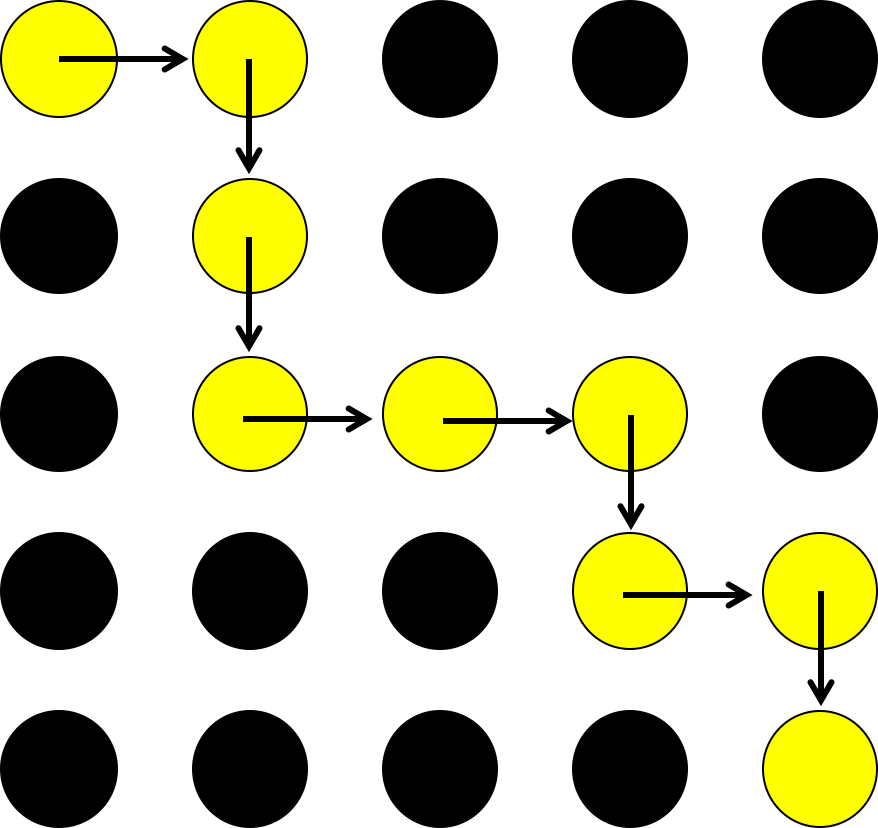

You probably have your own examples, but what they all demonstrate is that humans have a tendency to slip into “One True Way” thinking. There are at least two reasons why. The first can be called the “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” principle. I can illustrate by reference to some well known laboratory experiments (Schwartz, 1980, and Page & Neuringer, 1985) in which pigeons were confronted with a bank of lights like those at right. At the start of a trial, the top, left light was illuminated, and the others off. Subjects could make either of two responses: One moving the light rightward, and the other moving it downward. Getting the light to the bottom, right earned food, regardless of the specific path the light took.

The results? No two pigeons created the same path, but most, once a path was reinforced, they each kept doing it the same way (unless variability was expressly reinforced). By analogy, if a particular way of designing experiments or addressing a practice problem tends to work for us, well, reinforcement does what it does, and gets us to repeat ourselves.

The second thing to consider is that we’re verbal creatures, prone to generating verbal rules for what to do when. Rule-following is not just an individual thing; it’s socially mediated, to encourage us all to follow the same rules. When people write textbooks and journal articles they give “best practices” rules a broad audience. We’re impelled to respect these rules by a verbal community of peer reviewers who evaluate our manuscript submissions and fellow practitioners who pass judgment on our assessment and treatment strategies.

Rules for science and practice are useful because they are (relatively!) easy to follow and they help to insulate us from the worst consequences of doing science or practice badly. And good thing, because the logical thinking demanded by science and practice does not come naturally to most people. Every semester I have a roomful of sophomores in my research methods course who remind me of this. We need “best practices” rules to protect us from the worst mistakes, and we love how those rules assure us that we’re “doing it right.”

But here’s the thing. Unless you believe that we know everything, that we’ve got the best possible solutions to every problem, you have to regard “best practices” as both context-dependent and temporary. They’re contextual because no solution fits every circumstance, and they’re temporary because new stuff is being discovered all the time. That’s why, in The Shaping of a Behaviorist, Skinner wrote, “Regard no practice as immutable. Change and be ready to change again.”

Can Spontaneity and “Best Practices” Co-Exist?

I don’t have any ironclad answers to the problem of balancing constructive rules and contingency shaping. I’m inclined to argue that our training as behavior analysts should demand more contextual thinking.

Example: Our textbooks and classes task lists for certification address when Strategy X is suitable, but do they give equal attention to when Strategy X is a poor choice? Discrimination learning requires examples and nonexamples, so doing more to emphasize that every strategy has both applications and misapplications could help.

But as long as our social milieu remains unchanged, as long as behavior analysts punish those who stray from “best practices” and reward only those to adhere to them, we’re going to get scientific and professional stereotypy. So here’s a question, really the question: How could you train behavior analysts so that they reward others’ curiosity and procedural creativity… but also recognize when the “rule breaking” has gone too far? If you have an answer to that, I’d love to hear it.