Hallucinating, says the dictionary, is perceiving something not currently present.

This is usually understood as a symptom of psychiatric disturbance, such as when the “Son of Sam” killer, David Berkowitz, allegedly heard heard the voice of a demon, emanating from a black dog, ordering him to kill; or when Nikola Tesla, in his unhinged later years, claimed to receive telepathic communications from a pigeon (with whom he was madly in love).

Colorful examples like these obscure the fact we all “hallucinate” on a regular basis. For example, though no one else has directly observed my private events, I do see “mental images.” And so do you (I’m pretty sure). These “pictures in the head” can portray events of the past (like my mother’s furious face on the day, 58 years ago, when I broke the glass on our family’s front door), or even things never actually experienced (like my wishful 6th grade self’s first kiss with the magnificent Melinda Pfeiffer).

As with so much else, Skinner had an explanation for such things. In Science and Human Behavior he described “seeing in the absence of the thing seen” as a byproduct of high motivation and restricted access, as when a man momentarily “sees” his absent lover in a crowd that could not possibly contain her. Skinner’s example depends on two assumptions: (a) perceiving is behavior normally under very specific stimulus control, although (b) when motivating operations are high substantial generalization may take place. In other words, in (b), sometimes the woman needn’t be present in order to be seen [see also Postscript 1].

There are some things Skinner’s account doesn’t explain, starting with why mental imagery is so common. Just about everyone reports a very active internal life. We can daydream about an absent lover or a deceased favorite pet. We can picture ourselves hiking the Grand Canyon, which we have seen only in photographs. We can repeatedly replay a long-ago argument with an estranged colleague. [And of course, while sleeping we can dream, though that may be a more complicated topic.].

According to some estimates daydreaming (common topics: social relationships and the future) consumes 25% to 50% a person’s waking experience. And if you think daydreaming is always an inconsequential quirk of human behavior, see Postscript 2.

One of the first things I was taught about behavior is that if there’s a lot of it, there must be a reinforcer. Behavior that is common must serve a purpose. What about mental images? What’s responsible for their high frequency of occurrence? Skinner explained that the man who “hallucinated” his lover in a crowd experienced conditioned reinforcement. The lover was a source of reinforcers; seeing had been paired with various experiences of her; thus seeing, via classical conditioning, became a conditioned reinforcer [see also Postscript 3].

That’s pretty straightforward, but when we launch into the imagining of never-happened experiences, things are more complicated. Probably relational frames help here (for instance, because I had kissed a few girls, and Melinda Pfeiffer was a girl, transitively speaking I could “experience” kissing Melinda Pfeiffer, even though that never really happened (and, if my use of “girls” here offends, remember, this was 6th grade for goodness sake).

You might notice that earlier I said “just about everyone” sees mental imagery. But not everyone. This highlights a possible hole in Skinner’s account of “seeing in the absence of the thing seen,” because if mental imagery is simply a side effect of commonly-occurring experiences, then we would expect it to be ubiquitous. Yet in the condition known as aphantasia, mental imagery does not occur. Research into the condition tends to focus on atypical brain function, not behavioral processes:

Early studies have suggested that differences in the connections between brain regions involved in vision, memory and decision-making could explain variations in people’s ability to form mental images. Because many people with aphantasia dream in images and can recognize objects and faces, it seems likely that their minds store visual information — they just can’t access it voluntarily or can’t use it to generate the experience of imagery.

It’s estimated that up to 4% of the population is aphantasic (see Postscript 4), and affected individuals could serve as an acid test for Skinner’s account of “seeing in the absence of the thing seen,” in two ways. First, in at least some cases, it should be possible to reconstruct atypical behavioral histories that explain the failure of mental imagery to emerge. Second, if behavioral history explains mental imagery, then it should be possible to design experiences to create it, even in aphantasics. And if mental imagery serves an important function, then we ought to be talking about how behavioral interventions would accomplish this.

So, if you think you’re a savvy behavior analyst, ask yourself: What experiences would you program? In addition to factors Skinner mentioned, I suspect you’ll need to take into account relational networks and derived stimulus relations, but for now the key point is that aphantasia is something behavior analysts don’t seem to have addressed, but should, for both theoretical and practical reasons. Aphantasics can’t do something that can be advantageous to other people, and if mental imagery is behavior, and we understand behavior as well as we say we do, then we ought to be able to teach it.

Now, aphantasia is only one layer of an interesting onion. Once we start developing research-driven accounts of mental imagery, we open the gates to a lot of other private-event phenomena, including the aforementioned hallucinations of the mentally ill (see Postscript 5), “phantom limb” syndrome, “third man” experiences, and even the “phantom vibrations” people feel after losing a cell phone.

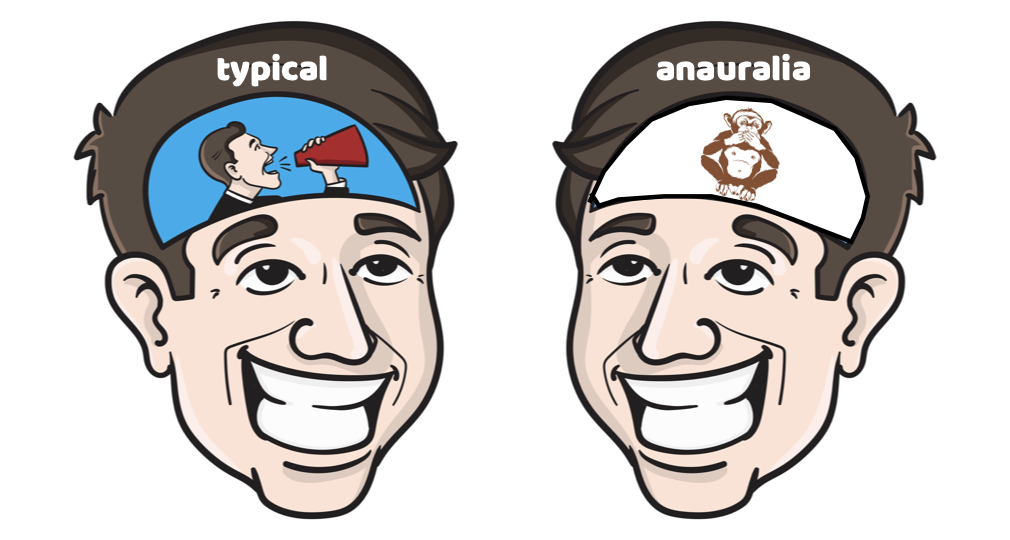

And then there is anauralia, in which people lack an “inner voice.” In other words, unlike most of us, they can’t imagine voices and don’t perceive speaking in the absence of a speaker (see Postscript 6). I find this one particularly interesting because Relational Frame Theory assumes that self-talk is an unavoidable component of the human experience (particularly in instances of psychological suffering). So…

- If anauraliacs lack self-talk, and are they immune to internal-verbally-mediated suffering (like that emphasized in RFT and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy)?

- If anauraliacs don’t have an inner voice, what’s the implication for RFT and ACT?

- If hearing inner voices confers benefits (why else would most people hear them?), what experiences could build up this repertoire? Could that repertoire be built up to be beneficial only?

Behavior analysis is great — in fact, wherever it has been applied in earnest, it has delivered answers and solutions. We cannot assume, however, that it is capable of doing so in every instance. By that I mean that answers and solutions are empirically defined, and phenomena like those mentioned here show that we are a long way from verifying that we have a truly general-purpose science of behavior.

One of the hallmarks of the philosophy underpinning our science, radical behaviorism, is that, unlike some other forms of behaviorism, it sees no distinction (other than socially-objective observability) between public and private behavioral events. That’s great in principle, but thumb through any behavior analysis journal or treatment manual, and you’ll see attention almost exclusively to public behavior. If public and private events truly are equally important in our science, shouldn’t we do more than simply take on faith that we have all of the answers regarding private events?

We behavior analysts have not systematically applied our science to private events. And I get it: There are real challenges to working with phenomena no experimenter can directly observe (studies of aphantasia, for instance, rely on self reports and brain scans, neither entirely satisfying from a behavioral perspective). But I say it’s better to have studies with limitations than to have no studies at all, especially when we’re talking about stuff as ubiquitous to the human experience (for everyone other than aphantasics, anyway) as mental imagery.

Postscript 1: Black Scorpions in Your Head

Digression: Writing about “Seeing in the absence…” got me free-associating about Skinner’s famous “No black scorpion” episode. The Philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, while wrestling with the notion of referent (stimulus control) in verbal behavior, challenged Skinner to explain the variables controlling him saying, “No black scorpion is falling on this table.” As Skinner wrote later, that challenge prompted him to begin composing Verbal Behavior. Skinner interpreted Whitehead’s statement partly as metaphorical (I’ll spare you the details, but in lay terms perhaps the scorpion was symbolic of Whitehead’s feelings about behaviorism; you can find a brief, technically accurate, and pretty accessible summary of this position in the Philosophical Naturalism blog). A casual observer might instead assume that Whitehead spoke of scorpions because something had prompted him to imagine one. This highlights a challenge of studying mental imagery: We know of its existence in another person primarily when it’s spoken of, though speaking doesn’t necessarily verify its existence. In Whitehead’s case, if metaphor was afoot there would be no need of a mental image (however, once he spoke I’ll bet some in the room promptly imagined that absent scorpion, as, perhaps, did you just now).

Postscript 2: Pathological Daydreaming

For roughly 2% to 3% of adults — that’s at least on par with the prevalence of autism, by the way — daydreaming occurs so often that it interferes with adaptive functioning. Excessive daydreaming seems to correlate with severity of psychological symptoms. And although my quick search turned up nothing specific on daydreams in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, presumably ACT would regard daydreaming as a potential form of experiential avoidance (e.g., see Postscript 4). Thus, to say that a behavior that is common must be functional does not always imply a function that enhances well-being..

Postscript 3: About “Seeing in the Absence…”

Skinner’s account focuses on generalization, so start by thinking in terms of a stimulus generalization gradient. The experiential S+ for “seeing the lover” is being in her proximity. But a variety of stimulus conditions may be similar enough to occasion “seeing” — think of women with the same build and hair color, for instance. Given the power of derived stimulus relations, a different kind of “extension” of stimulus control also is possible. Various stimuli that have been associated with the lover [a type of garment, a favorite place, etc.] — things bearing no physical similarity to the woman — should also occasion “seeing.”

Postscript 4: Defining Aphantasia

To suggest that 4 out of 100 people may have aphantasia is a bit of an overstatement, as the vividness of mental imagery apparently varies considerably across people. Technically, only those who totally lack mental imagery are called aphantasic, although for some individuals mental imagery, while present, apparently is pretty rudimentary.

Postscript 5: ACT & Hallucinations

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy has been applied to pathological hallucinating in a few instances; see Veiga-Martinez et al. (2008); Guadinao et al. (2010); and Shawyer et al. (2012), though sometimes with mixed outcomes (Shawyer et al., 2018)

Postscript 6: The Inner Voice: Beyond Watson

Yes, I’m aware of the long-running concept of “inner voices” as sub-vocal speech — that is, the listener is also the speaker, though perhaps at times unaware of this. J.B. Watson, for instance, held a view like this, though his position is often misunderstood. Anyway, this is a big topic, way beyond the scope of the present post, BUT a fully developed behavioral account should be able to clearly distinguish between subvocalization and “hearing in the absence of a speaker who is not me.”