Guest Blog Authored By: Ji Young Kim, Ph.D., BCBA-D, Penn State Harrisburg

Dr. Ji Young Kim is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Penn State Harrisburg and a doctoral-level Board Certified Behavior Analyst. Dr. Kim earned her Ph.D. and M.A. in Applied Behavior Analysis at Teachers College, Columbia University, and her B.A. in Psychology at Barnard College, Columbia University. She has published in peer-reviewed journals, and her work has been recognized through numerous awards and grants including the APA Division 25 SEAB Applied Behavior Analysis Dissertation Award, the NYSABA research award for two consecutive years, and the SABA Sidney W. and Janet R. Bijou Grant. Dr. Kim is interested in understanding decision-making behavior and developing effective procedures to enhance learning for individuals with and without developmental disabilities. She is also passionate about and has started exploring the intersection between verbal behavior and decision-making.

Self-Control: A Tough Shell to Crack

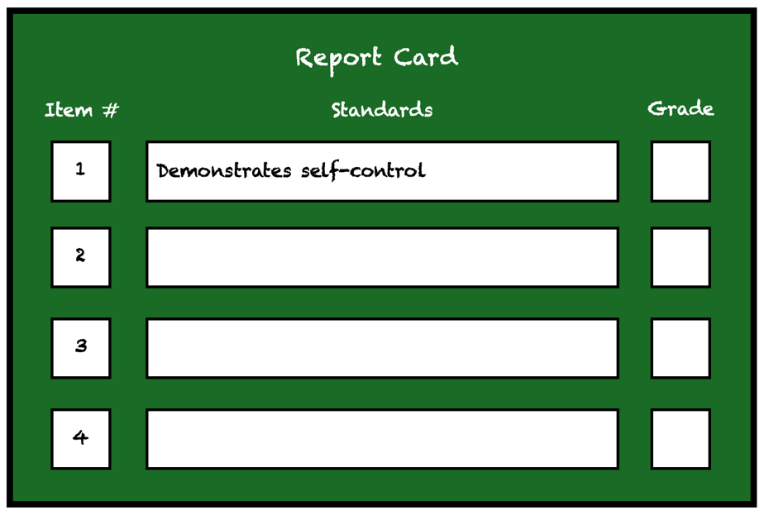

When I was a second-grade teacher, report cards were sent home three times a year. It was a great way to communicate with parents about how their children were doing in school. The report cards always started with math skills, followed by reading, and then social studies. The ‘classroom behavior section’ started with a question that immediately caught my eye – it asked me to rate how well my student “demonstrates self-control.”

Image made by the author

I was taken aback by this question. Sure, some students who were “self-controlled” sat nicely during instruction throughout the day and waited their turn before talking aloud, while some students who were more “impulsive” got upset when they needed to wait for their turn to play with a toy. But it was unclear what distinguished a student deserving a score of ‘5’ from a student deserving a ‘3’, or a student deserving a ‘3’ over a ‘1’ (assuming that ‘5’ meant a student had great self-control and ‘1’ meant the opposite). It was rare for a student to always sit nicely and follow directions or get upset while waiting for their turn. That was just not how second-graders, even adults, behaved. When I asked around, every teacher I spoke with had similar, yet varying, definitions of self-control they used to score the report card. I turned to research with the hope of finding some answers.

What Do We Know About Self-Control?

Self-control has been a topic of interest in education, psychology, and beyond for quite some time. While it would be impossible to sum up all the literature in this post, the number of hits you get from a brief search on Google Scholar using the search term “self-control” speaks to the popularity of the topic – about 2,450,000 hits as of mid-2024! Similar terminologies and constructs used in other disciplines, such as self-regulation, executive functions, and delay of gratification, further indicate the widespread interest in understanding the phenomenon1.

Research in behavior analysis helped to shed some light on the concept of self-control. What I found was that self-control can be defined as selecting a larger, later reward over a smaller, sooner reward when these two options are presented concurrently (Rachlin & Green, 1972). Selecting the smaller, sooner reward was a tendency toward making an impulsive choice. For instance, an individual with greater self-control would forgo watching an episode of Friends in the morning (smaller, sooner reward) to get to work on time (larger, later reward). This phenomenon might remind you of the famous Marshmallow Test. In this test, children were asked to select between getting one marshmallow right now (smaller, sooner reward) or getting two marshmallows later (larger, later reward). At the time, the results showed that children who waited for the two marshmallows had better coping strategies during the wait and even had better life outcomes.

Selecting the larger, later reward was not always optimal (e.g., buying a house when the mortgage interest rate is high compared to short-term renting), and selecting the smaller, sooner reward was not always bad (e.g., enjoying a short break after running for a mile rather than continuing to run). However, there are cases when choosing the smaller, sooner reward is unavoidable or results in detrimental consequences. For example, a young student may continuously leave or run away from a classroom instead of raising their hand to ask for a break. Self-control training procedures were created for these cases to increase self-control or, in other words, teaching an individual to select the larger, later reward over the smaller, sooner reward. Some procedures involved progressively increasing the delay to a larger reward, and others involved providing intervening activities during the wait for the larger reward (Finch et al. 2024).

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

How Does Verbal Behavior Relate to Self-Control?

As teachers, we may often encounter the concept of “using our words.” For example, I used this phrase when I encouraged my students to communicate their wants and needs vocally instead of resorting to hitting or taking toys from their friends. If we look closely at the phrase, it conveys that using language serves as a meaningful alternative to engaging in challenging behavior, akin to demonstrating self-control. Behavior analysts know this very well. Several self-control interventions developed by behavior analysts directly investigated the role of verbal mediation such as self-stated rules. For example, Binder et al. (2000) showed that individuals more frequently selected the larger, later reward when they told themselves, “‘If I wait a little longer, I will get the bigger one” while the delay to the larger, later reward slowly increased.

But how does this work? Self-generated rules may function as discriminative stimuli? When an individual selects the larger, later reward, they may be saying, “If I wait longer, I can get the larger reward,” which, in turn, signals the reward’s availability and increases the value of the larger, later reward. The behavior itself (i.e., selecting the larger, later reward over the smaller, sooner reward) may not be sufficient to explain the mechanism of how or why an individual selects the larger, later reward over the smaller, sooner reward. Perhaps, the verbal behavior of the “self” is essential in explaining self-control.

The Power of Speaking and Listening to Yourself

If you listen closely, you might notice that you often talk to yourself when you are waiting for something – you might say phrases such as “one more minute” or “just two more days.” Just like that, self-control comes when we say what we will do and then perform the behavior. For us to follow the self-generated rules, we must hear ourselves speak the rules. For example, I told myself this morning, “If I work out, I can get a big burger for lunch.” I would need to hear myself say the rule, either quietly or aloud, and then work out with the promise of getting a big burger for lunch (of course, being your own contingency manager comes with its own set of problems – this should be another interesting topic for discussion!).

Image by 愚木混株 Cdd20 from Pixabay

For the self-generated rules to control our future behavior, it may be important for them to have strong stimulus control. In verbal behavior, Incidental Bidirectional Naming (Inc-BiN) indicates the joint stimulus control for speaker and listener behavior (Horne & Lowe, 1996). Simply stated, the speaker and listener within an individual are integrated, and this individual can speak with understanding of what they are saying. For a self-stated rule such as “I will wait one more minute” to help someone wait for the larger, later reward, an individual needs to listen and speak to themself.

Data from my lab (Kim, 2024) preliminarily supports this idea. This study showed that second graders who had more self-control (i.e., discounted the value of $100 more slowly) showed greater accuracy in an Inc-BiN task, which consisted of listening to novel names and later identifying and saying those names. For example, an experimenter would expose a student to the Samsung logo and vocally state the name “Samsung” to the student. Later, the experimenter would test if the student could identify the logo from a set of three and say “Samsung” when the logo was displayed on a screen. Using this example, a student who had greater self-control could identify the logo and say the name “Samsung” better. The results preliminarily showed that students who spoke with an understanding of what they were saying had a higher level of self-control. It was possible that these students more fluently generated self-stated rules as a speaker and then listened to their own rules recited as a listener, leading to greater self-control.

The idea that language and self-control are related is not new outside of behavior analysis research. For example, several cross-sectional studies have shown that overall, the more language a child has, the better self-regulation skills they will demonstrate (Cournoyer et al., 1998; Vaughn et al., 1984). Longitudinal studies have also shown that vocabulary use predicts the level of self-regulation in toddlers (Vallotton & Ayoub, 2011), and language ability predicts later self-regulatory skills (Petersen et al, 2015). However, the role of self-stated rules in controlling one’s behavior to wait better for the larger, later reward remains unclear. Maybe it is time for us to investigate the concept of self-control from the perspective of Skinner’s verbal behavior (1957) and examine the role of the “self.”

So, What Did I Learn?

When we put everything together, perhaps the development of essential decision-making skills such as self-control should accompany verbal behavior, particularly how an individual speaks and listens to themself. To teach self-control, it may be essential to teach someone to speak and listen, not only to others but also to themself.

So, what happened with the report cards? I did the best I could. Unfortunately, at the time, I could not find any systematic guidelines for rating self-control skills in second graders. I ended up giving scores in the fairest way I could think of – a self-made rubric. Although this was not the ending that I had hoped for, at least I learned that behavior analysis, particularly verbal behavior, showed promise in addressing this enduring question of what self-control meant and how it can be taught.

References

Binder, L. M., Dixon, M. R., & Ghezzi, P. M. (2000). A procedure to teach self-control to children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2000.33-233

Cournoyer, M., Solomon, C. R., & Trudel, M. (1998). “Je parle donc j’attends?”: Langage et autocontrôle ches le jeune enfant [I speak then I expect: Language and self-control in the young child at home]. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 30(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085807

Diamond A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Finch, K. R., Chalmé, R. L., Kestner, K. M., & Sarno, B. G. (2023). Self-control training: A scoping review. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 17(1), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-023-00885-y

Horne, P. J., & Lowe, C. F. (1996). On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 65(1), 185–241. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1996.65-185

Kim, J. Y. (2024). Delayed consequences in general education through the lenses of delay discounting and verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-024-00202-w

Mischel, W., Ebbesen, E. B., & Raskoff Zeiss, A. (1972). Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(2), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0032198

Petersen, I. T., Bates, J. E., & Staples, A. D. (2015). The role of language ability and self-regulation in the development of inattentive-hyperactive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 27(1), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000698

Rachlin, H., & Green, L. (1972). Commitment, choice, and self-control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 17(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1972.17-15

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Vallotton, C., & Ayoub, C. (2011). Use your words: The role of language in the development of toddlers’ self-regulation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.09.002

Vaughn, B. E., Kopp, C. B., & Krakow, J. B. (1984). The emergence and consolidation of self-control from eighteen to thirty months of age: Normative trends and individual differences. Child Development, 55(3), 990–1004. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130151