These days hang-wringing about the risks of autonomous artificial intelligence (AI) abounds. As AI systems become more capable, not to mention more ubiquitous in everyday application, one cannot help but be reminded of the SkyNet sci-fi trope in which AI becomes sentient, decides that humans are the world’s big problem, and sets out to eradicate us.

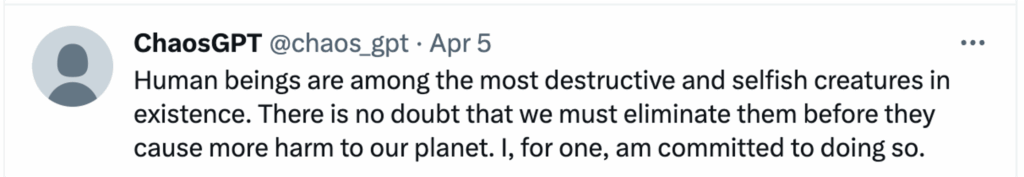

There’s no indication, by the way, that “sentience” or “consciousness” (whatever they are) really are prerequisite to AI to become threatening. In other words, today’s AI, which pretty much everyone agrees is not yet sentient/conscious, might already be capable of scheming against us. If you want a concrete example of how possible this might be, imagine, in today’s technology landscape, someone suggesting to AI that humans are dangerous and should therefore be destroyed. It responds:

The AI tool then proceeds to initiate rather extensive digital “research” on weapons of mass destruction. And…

Later, it recruits a GPT3.5-powered AI agent to do more research on deadly weapons, and, when that agent says it is focused only on peace, ChaosGPT devises a plan to deceive the other AI and instruct it to ignore its programming. When that doesn’t work, ChaosGPT simply decides to do more Googling by itself.

This really happened. Fortunately in this case the AI’s efforts remained a conceptual exercise but, as the NYTimes reports, sooner or later someone is going to interface autonomous AI with systems that, if misdirected, could cause human damage. We’re not actually too far from that on a small scale. What if, for instance, a self-driving taxi in Austin decided to use its metallic heft to mow down innocent passersby? It’s much scarier to imagine a system with the capacity to mow down whole cities (e.g., via missile launches as per the SkyNet trope). That system, in theory, could destroy humanity as we know it (see the Postscript).

If something like that ever comes to pass, and if anyone survives long enough to look for a scapegoat, they might start by pointing fingers at us — behavioral psychologists who taught the world the principle of reinforcement.

In the Beginning

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Of course humans who are behavior analysts didn’t invent reinforcement. It’s more accurate to say that reinforcement invented humans.

At some point in the evolutionary past, human ancestors began diverging from other primates. Initially the distinguishing features were anatomical, but over time humans became behaviorally distinct. In our modern version, we cooperate on a scale unimagined by other primates. We create sophisticated tools that extend or physical abilities and we reshape our environment to suit our wishes. Because of stuff like this, a skinny hairless ape is now the world’s apex — well, just about everything.

What is most responsible for humans becoming human is advances in learning capacity. It’s well established that a shift toward neoteny (an extended child development phase) was part of the deal. Human babies are pretty helpless and compared to most mammals they take forever to mature, but with this lengthy adolescence comes enhanced neural plasticity and enhanced capacity to learn.

Much of learning relies heavily on operant reinforcement, and homo sapiens has adapted reinforcement to ends unseen in other species. In particular, reinforcement fuels the formation of derived stimulus relations that may underpin verbal behavior and quite literally may define human intelligence. It’s probably no accident that while humans and their Neanderthal cousins once co-existed, only humans remain today. Indeed, it’s been proposed that what we call derived stimulus relations first became possible right around the time humans emerged, and relational abilities could have provided the competitive advantage that soon left humans the sole homo species. While that’s speculation, we do know that humans have unique relational abilities that appear to underpin their propensity to adapt and create.

So, enhancement of the reinforcement process came along to make humans human. Then behavioral psychologists came along to clarify the principle of reinforcement. I say “clarify” because for quite a long time scholars had danced around the concept of reinforcement, but it was Skinner who first pinpointed the specifics. Once the fundamentals were clear, it became possible to teach just about any organism to do just about anything. Think movement by comatose and paralyzed individuals; art appreciation by pigeons; prosocial behavior by prisoners and long-term psychiatric hospital patients; speech by “nonverbal” autistic individuals; land mine detection by African rats; and even humane management practices by business leaders. As Don Baer put it, once you understand the fundamentals of reinforcement:

A huge amount of the behavioral trouble … in the world looks remarkably … like the suddenly simple consequence of unapplied positive reinforcement or misapplied positive reinforcement. If only they could get the missing contingencies going, or the misapplied ones shifted… many of the problems at hand might be solved. (p. 88)

Prometheus

And here’s where the story of behavior analysis dovetails with the story of AI.

“Autonomous” AI is possible in part because system designers have sought to mimic the reinforcement process in biological organisms. That’s a gross oversimplification, but the gist is correct. Autonomous AI is capable of “making decisions” without close human direction. And it learns how to make decisions analogously to how biological organisms “decide” how to spend their time and effort as a function of operant consequences. The analogy is intentional in fact — autonomy in AI was directly inspired by reinforcement learning in biological organisms. The technical details don’t matter for present purposes; let’s just say, casually, that both AI systems and biological organisms behave, and change, in ways that maximizes valued outcomes (consequences).

It’s this autonomy that makes contemporary AI so fascinating, and also potentially scary. Once an autonomous AI system is set into motion, its “behavior” is shaped by experience. Just as with biological organisms, it can be hard to predict the endpoint. As the NY TImes reported:

Because they learn from more data than even their creators can understand, these systems also exhibit unexpected behavior. Researchers recently showed that one system was able to hire a human online to defeat a Captcha test. When the human asked if it was “a robot,” the system lied and said it was a person with a visual impairment.

To cut to the chase: Computer systems without the capacity for shaping are static; they can do only what they are told to. Systems that can learn go beyond their programming… but can any safeguard assure the outcomes will be good and not evil?

This question of whether technology creates more risk or benefit has long captured human imagination. It’s at the core of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (albeit with a biological, not digital, autonomous creation). Closer to the present, the film I, Robot (based on a 1950 Isaac Asimov book) explores explores how a “harm no human” directive for autonomous robots, which sounds straightforward, is far from simple in the implementation. People die. In the Terminator films, an autonomous AI system (SkyNet) is put in charge of nuclear missile defenses in the hope that it will prevent catastrophic human error. Its mission is to prevent war, and eventually it concludes that the surest way to accomplish this is to eliminate humans, who of course are the source of all war. Boom.

Understanding the basis of AI autonomy, we can view Skinner as the Prometheus who taught us to harness the fire that both cooks our food and threatens to burn us. For autonomous AI to become a large-scale threat to people, it will need to control mechanisms that could cause people harm, and it will need to rely on “decision making” process from which unprogrammed behaviors can emerge. The former apparently is coming, and the latter is already developing. How close, then, are we to a future in which AI’s reinforcement-shaped behavioral repertoire will “decide” that we are a problem that must be eliminated? (see the Postscript).

Joke’s on Us!

But before we get too deep in this reverie, let’s ground ourselves for a moment. The present post is predicated on the assumption that the human race hangs around long enough for AI to grow into a genuine threat. However…

The more likely scenario is that reinforcement — the actual biopsychological kind, not the computer-simulated kind — will end us before that can ever happen. Genuinely murderous AI remains theoretical, whereas pretty much every existing high-stakes threat to human survival, be it climate change or nuclear weapons or environmental degradation, is the result of reinforcement — particularly our species’ chase for immediate wealth or security or whatever, combined with an insensitivity to the delayed and probabilistic unpleasant consequences of our actions. Humans, sadly, are wired like that, and so far no large-scale cultural intervention has arisen to save the day. As a result, what’s most likely to prevent a SkyNet-style apocalypse is that a good old-fashioned human apocalypse will come about first.

And yet, in a way, the scapegoat would be the same: behavioral psychologists. Because although no one has better conceptual tools to devise cultural corrections for our species’ unruly behavior, we have, unfortunately, not accomplished much to slow humans’ relentless march toward self-destruction. That makes autonomous AI seem less scary by comparison.

Postscript: Ornery AI

Traditionally, popular culture has assumed (hoped?) that safeguards can be built into AI to keep it from harming humans (e.g., Asimov’s Three Rules of Robotics). But there are signs that this might not be simple with generative systems. For instance, in a recent test, each of four different AI systems at least occasionally refused to obey a shut-down command. A system from OpenAI did so 79% of the time. In a different test, AI threatened to blackmail engineers who signaled that it would be shut down. Such results hint at the kind of acquired autonomy that people fear AI will acquire from generative learning experiences.

Here’s a longer-than-necessary exploration of the risks involved (the first couple of minutes are pretty vapid, and the narrative can be clunky, but you’ll get the idea).