Guest Blog post by: Cynthia Livingston, Ph.D., BCBA-D; Alexandra Cicero, M.A., BCBA; and Grace Lafo, M.S., CF-SLP

Cynthia Livingston, Ph.D., BCBA-D is an assistant professor in the Severe Behavior Department at The University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Munroe-Meyer Institute. Her primary responsibilities include clinical case management, mentoring masters and Ph.D. students in their research and clinical endeavors, and teaching. Dr. Livingston is primarily interested in fine-tuning assessment and intervention approaches through the promotion of choice and autonomy and has a special interest in working with caregivers and empowering them to be an integral part of their child’s success. Her other special interests include small dogs, Trader Joe’s, yoga, kombucha, and planning trips! Check out Dr. Livingston’s Lab on Instagram @the_livingston_lab.

Alexandra Cicero, M.A., BCBA

Alexandra Cicero is a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst currently working in the Severe Behavior Department at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Munroe-Meyer Institute. She specializes in assessing and treating challenging behavior in individuals diagnosed with autism and other developmental disabilities. Her clinical and research interests include functional communication training (FCT), caregiver training, mand modality preference, and increasing generalization and maintenance of treatment effects. Alexandra is passionate about creating meaningful, individualized treatment plans and collaborating closely with families to promote long-term success across settings. She also enjoys teaching and mentoring future behavior analysts and values creating inclusive, supportive learning environments.

Grace Lafo, M.S., CF-SLP Grace Lafo is an outpatient pediatric speech-language pathologist and LEND clinical fellow at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Munroe-Meyer Institute. Grace received her master’s in Communication Disorders and Sciences and a certificate in Behavior Analysis and Therapy from Southern Illinois University. She is also completing her training to be a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst. Grace’s clinical and research interests include augmentative and alternative communication, caregiver training, and interprofessional collaboration.

A note before we begin:

This blog post focuses on situations where caregivers’ and learners’ preferences for communication modalities do not align. Learner and caregiver preferences both matter. Notably, we are discussing preferences within the context of the replacement behavior for challenging behavior, not preferences for the learner’s full communication repertoire.

Still, in treatment planning, we may find that one functional communication response modality is better suited to replace challenging behavior that interferes with learning, daily living, social interactions, or access to reinforcement.

Behavior analysts are still working to understand how best to navigate situations where communication preferences don’t align—whether between the learner and caregiver or among caregivers, providers, and the behavior analyst. This post offers one perspective, with full recognition that this is an evolving area of practice.

Now, on to our regularly scheduled programming!

Overview of Functional Communication Training

As many behavior analysts have experienced, learners may engage in challenging behavior. Challenging behavior, like aggression and self-injury, is stressful. It may lead to short- and long-term interruptions to programmed instruction and may intensify in severity and frequency if left unaddressed (Kurtz et al., 2020). One intervention to reduce challenging behavior is functional communication training (Carr & Durand, 1985).

Functional communication training is a specific form of mand or request training that teaches individuals more effective ways to express their wants and needs (Figure 1). Functional communication training uses variables that evoke and maintain challenging behavior to identify and promote a functional communication response (functional communication response)—a mand—that serves the same purpose (Tiger & Hanley, 2008).

Functional communication training is a multi-phase function-based intervention that starts with a functional behavior assessment and ends with treatment generalization. Between the functional behavior assessment and generalization, differential reinforcement of an alternative, appropriate response is introduced. Here, we teach and reinforce the functional communication response, and, in many cases, challenging behavior no longer results in the functional reinforcer. The key is that the replacement response is directly linked to the function of challenging behavior.

Disclaimer: A complete breakdown of functional communication training is beyond the purpose of this blog post. For a comprehensive overview of functional communication training, we recommend checking out Carr & Durand (1985)!

Case Example 1

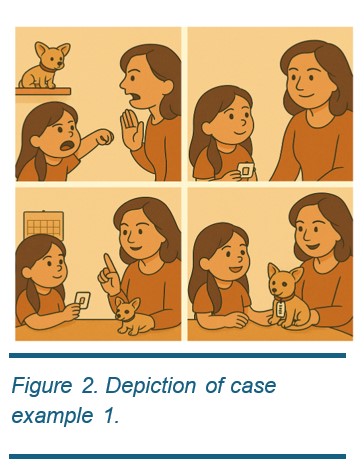

Betty was been referred to your clinic for aggression (punching). Betty’s mother reports that Betty punches other people in all settings. It seems to happen when “Betty can’t have what she wants, especially when she wants her favorite stuffed animal.” Betty’s mother is regularly called away from work to pick Betty up from school. You complete a functional behavior assessment and hypothesize Betty’s aggression is maintained by access to tangibles. You implement functional communication and teach picture exchange as your functional communication response modality. Now, Betty has learned that exchanging a picture card results in access to her preferred stuffed animal. (Figure 2)

Functional communication training is an effective intervention for socially mediated challenging behavior, but that does not mean it’s immune to ineffectiveness or inefficiencies. It may not be fully effective if, for example, the functional communication response modality is not mastered, preferred, or reinforced by others.

Functional Communication Response Selection

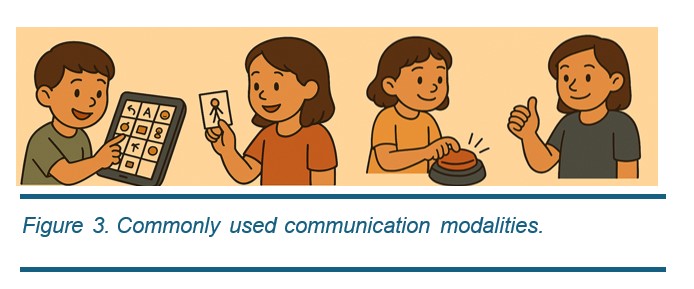

Not all learners communicate vocally, so it is important to consider various functional communication response modalities. A functional communication response modality is the specific topography of communication used within functional communication training.1 Any communication modality that deviates from vocalizations is considered augmentative and alternative communication. Commonly used modalities include manual sign, gestures, speech-generating device (speech-generating device), picture exchange, and vocalizations (see Figure 3).

The selection of the functional communication response modality can be a delicate process. Just because the learner cantalk, doesn’t mean talking is an easy way for them to communicate (especially when they’re already frustrated). When selecting a modality, practitioners should consider the learners’ existing skill sets and preferences. What is the easiest and preferred modality for them?

1Reminder of our note: Replacement Behavior, Not All Communication

Let’s clear up a common mis-communication (no pun intended) with a reminder of our note! For the purposes of this blog post, we are focusing on the use of an mand-modality preference assessment to identify the preferred functional communication response modality to be used in functional communication training. Although we highly recommend assessments like a mand-modality preference assessment or skills assessment in other contexts, we do not discuss these contexts here.

Considerations for Selecting the Functional Communication Response Modality

There are many variables to consider when deciding which communication modalities to include in functional communication training. We highlight considerations below and recommend Houck et al. (2023)’s practitioner’s guide (also see Table 1) to selecting a mand modality during functional communication training for more.

1. Individual factors, like communication history. Communication history refers to the use of different communication modalities a learner has been exposed to prior to functional communication training. For example, if the learner has used card exchange in the past, it may be easier for them to use it within the context of functional communication training. Conversely, if the modality has a history of co-occurring with challenging behavior, selecting a new modality may be considered. We recommend asking caregivers, teachers, or other providers about which modalities the learner has used before, if any.

2. Environmental factors. Is the modality recognizable and readily promoted and reinforced by others? Is it accessible and cost-effective? The learner may prefer to use the speech-generating device; however, these devices are costly and may not be covered by insurance (or replacements aren’t covered when the iPad screen shatters due to property destruction). These little details can make a big difference when choosing a communication modality that’s not just effective, but realistic for everyday life!

3. Related to environmental factors are Modality factors. Does the modality come with correlated stimuli or require extra tasks? For example, will the speech-generating device be charged when you need it most? Can you count on it making it into the backpack for the clinic every day? Other considerations include the modality’s ability to compete with challenging behavior. For example, you may choose gestures over vocalizations because pointing is incompatible with hitting.

Other individual factors include a history of challenging behavior. Let’s say a learner already has their own speech-generating device – amazing, right? That might make it a go-to choice for communication. But hold on! If the learner has a history of property destruction, the speech-generating device may become a projectile and get damaged or cause injury. In this case, gestures may be a better option.

The modality should also complement the learner’s existing abilities. For example, a manual sign would not be appropriate for a learner with extensive fine motor deficits. The practitioner may also consult with a speech-language pathologist to assess the learner’s skills and nominate modalities.

Finally, individual factors like learner preference should be considered: If all else is equal, find out which modality the learner (and caregivers) prefers.

Mand Modality Preference Assessments

Not all learners want to communicate via vocalization or card exchange – and that is okay! Some learners may prefer to use a button, gesture, or a speech-generating device instead. So, how do we determine which modality to include in functional communication training, especially if they can’t tell us? One method to identify preference is by conducting a mand-modality preference assessment (Winborn-Kemmerer et al., 2009; Ringdahl et al., 2008). Like tangible preference assessments, there is a variety of mand-modality preferable assessment procedural variations. We recommend selecting a format that works best for your learner and setting (see here for more).

Regardless of the format, we recommend ensuring proficiency (Ringdahl et al., 2008) with each modality or explicit teaching (Kunnavatana et al., 2018) prior to the mand-modality preference assessment. Once all modalities are acquired or excluded, we move to the pièce de résistance: The mand-modality preference assessment! This assessment is typically done in a setup where the learner can freely choose between different modality options, similar to a free-operant preference assessment. Once the learner uses a modality to communicate, they are given the functional reinforcer. Essentially, whichever modality they use the most, we deem their most preferred. Like tangible preference assessments, there are a variety of mand-modality preference assessment procedural variations. We recommend selecting a format that works best for your learner and setting (see here for more).

Understanding Preference: Why Do Learners Like What They Like?

While assessing preference is important, it is also beneficial to understand what influences it. There are many reasons a learner may favor one modality over others. Below, we highlight some of the most common factors that influence modality preference.

One big factor for learners is ease of use—or in behavior analytic terms, response effort. Simply put, learners are more likely to prefer the option that’s easier for them. But “easy” looks different for different learners.

For example, a learner with a strong vocal-verbal repertoire might find a vocal functional communication response to be the easiest option—after all, you can take your voice anywhere, whether you’re at home, school, or wandering the aisles of the grocery store (Figure 4). No equipment required! But for a learner with a speech impediment, talking might feel like climbing a mountain. In that case, even if gesture and vocal are in the learner’s repertoire, the easier response may be a gesture functional communication response.

Another variable that may influence preference is the presence or absence of correlated stimuli—the stuff that comes along with the communication modality and makes it more (or less) appealing (Figure 5).2 Take a speech-generating device on an iPad, for example. It might not just be about communicating; it’s about how fun and engaging the device itself is (especially if it is not being used exclusively to communicate—although we would not recommend this!). Lights, sounds, auditory feedback, favorite apps—all those extras can make a speech-generating device more preferred, even if the learner could use speech or gestures instead.

2Beyond preference, these correlated stimuli may also serve an additional function: acting as naturalistic discriminative stimuli (SDs) or cues that prompt the learner to emit the functional communication response. This can be particularly valuable in generalized contexts, where the communication response may otherwise be less likely to occur without the familiar features of the training environment.)

The history of reinforcement may also influence preference. If a learner has a long, positive history of using a certain modality—one that’s consistently been reinforced—it’s naturally going to climb higher on their preference list. On the flip side, if a communication attempt through a certain modality often went ignored (or worse, punished), you can bet (predict) that option won’t be their first choice.

But What about Caregivers?

Most of us would agree that incorporating learner preferences into behavior analytic interventions, like functional communication training, is essential. After all, promoting choice and autonomy isn’t just ethical—it has major implications for treatment effectiveness (Ringdahl et al., 2018). But it’s equally important not to overlook another key player in the process: The Caregiver.3

Caregivers aren’t just bystanders in their learner’s treatment; they’re the ones who are actually implementing treatment outside of therapy sessions. And here’s the (unsurprising) truth: if they don’t like the treatment, there’s a good chance they won’t use it (Kazdin, 1980). This is referred to as treatment adherence: the degree to which a person sticks to the components of an intervention as it was designed.

Beyond adherence, caregiver preference may also impact procedural fidelity—whether they use the intervention correctly. If a caregiver dislikes a specific modality, they’ll likely either use it incorrectly (fidelity), abandon it altogether (adherence), or both (oh my!). And we definitely don’t want that.

3This blog post is geared toward parents and legal guardians, but we also encourage you to connect with other relevant caregivers and service providers—like teachers, speech-language pathologists, and occupational therapists. They may want (and deserve) to have a voice in the process too (But that’s a topic for another blog post!).

Case Example 2

You are working with a caregiver whose child, Billy, uses a speech-generating device. Billy’s mom doesn’t love lugging the speech-generating device everywhere—it’s bulky, easy to forget, and feels like one more thing to manage when wrangling her kids into the car every day. Plus, Billy sometimes throws the speech-generating device when he’s upset. Because of these challenges, she often leaves the speech-generating device at home when they go out, even though it’s Billy’s primary way to communicate. Even at home, Mom feels hesitant to use the device; she tends to avoid it, staying physically farther away when Billy uses it to avoid getting struck with it. As a result, Billy misses important opportunities to practice communication with his speech-generating device, and the modality isn’t consistently reinforced. Meanwhile, Mom feels more comfortable responding to Billy’s gestures—so she’s quicker and more enthusiastic to reinforce those, even though it might not be the modality originally targeted in treatment. This case example highlights the nuance in selecting a communication modality.

Recommendations for Obtaining Caregiver Preferences

The best place to start is to ask the caregiver(s) directly. Bring it up during drop-off or pick-up, include it in your intake paperwork, discuss it during caregiver training sessions, send an email, or give them a call—use whatever communication method works best for the caregiver based on your previous interactions. The right approach depends on the type and depth of information you need. If you’re looking for something simple, like “I’d prefer you use gestures,” an informal conversation may suffice. However, if you need more detailed information or documentation—such as preferences that could impact service delivery or funding—it may be better to schedule a formal meeting. In some cases, formal assessments (like a survey or an augmentative and alternative communication evaluation with a speech and language pathologist may be necessary to document preferences and support access to needed tools.

What If Learner and Caregiver Preferences Are Different?

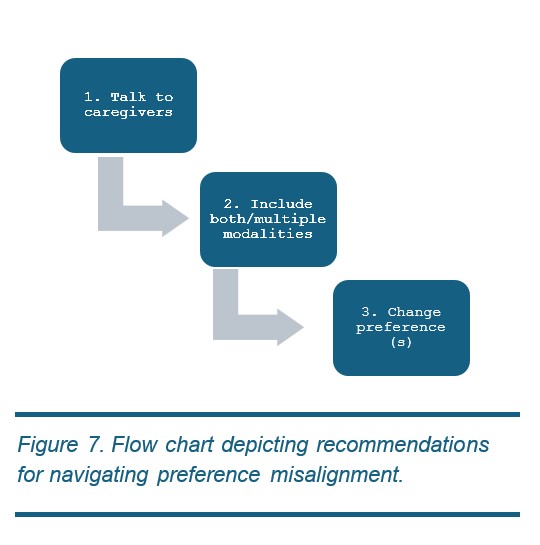

It might not come as a surprise that learner and caregiver preferences do not always align. Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to navigating caregiver and learner preference discrepancies. Nevertheless, we have some recommendations for where to start. (Figure 7)

- Have a conversation about communication goals—talk through the learner’s preferences, review any supporting data, and discuss how to move forward when there’s a mismatch in preferences. While there are more systematic strategies for shifting preference, sometimes simply having an open discussion with caregivers can lead to a change in their reported preference.

- Include both modalities (the caregiver’s and the learner’s most preferred modalities) in functional communication training. Although the research is mixed (Fuhrman et al., 2021) on the benefits of including multiple modalities, no research suggests it hurts to include more than one (i.e., it may not help, but it won’t hurt). If it results in making the caregiver happy, potentially increases the effectiveness of the intervention, and still incorporates the learner’s preference, this option may be a relatively easy and beneficial fix.

- If all else fails, work to change preference. Assuming you tried 1 and 2 and were met with barriers, we recommend attempting to shift the learner’s preference first. In other words, by modifying the consequences for preferred and non-preferred modalities, you’re intentionally making the preferred modality a bit less valuable than the alternative. This is called manipulating parameters of reinforcement (see Athens & Vollmer, 2010 for more). For example, you might deliver 20 seconds of attention for the preferred modality and 1 minute of attention for the non-preferred modality (if you aren’t sure what parameter to shift, we recommend this article).

Benefits of Changing Preference?

Shifting a learner’s preference to align with caregivers’ may feel a little “icky”, but here’s another perspective: one major benefit of honoring caregiver preferences is increased buy-in and adherence. When caregivers feel heard and supported, they’re more likely to consistently engage in treatment, which ultimately benefits the learner.

There’s another key benefit—you’re proactively preparing the learner for real-world challenges. By teaching them to use their functional communication response even when their preferred modality isn’t the most reinforced, you’re building resilience and flexibility into their communication system. This is a form of programming for treatment durability under less-than-ideal conditions.

That said, it’s still important to incorporate the learner’s preferences in meaningful ways throughout therapy. You can do this by conducting regular preference assessments, offering choices about what they’re working for, providing opportunities to take breaks, and letting them help structure parts of the session (like choosing the work schedule, when appropriate). Balancing caregiver and learner needs is possible—and crucial.

Final Thoughts (for now)

The identification of preferred modalities can be essential for selecting effective communication responses to include in functional communication training. Ultimately, the “real-world” success (social validity) of an intervention depends on caregiver adherence and practical implementation. By acknowledging and addressing discrepancies between learner and caregiver preferences, practitioners can foster more effective, sustainable communication interventions that empower both the learner and their support system. Ultimately, balancing preference, feasibility, and effectiveness leads to better long-term outcomes.

References

Athens, E. S., & Vollmer, T. R. (2010). An investigation of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without extinction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(4), 569-589. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2010.43-569

Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2), 111–126.

Fuhrman, A. M., Lambert, J. M., & Greer, B. D. (2021). A brief review of expanded-operant treatments for mitigating resurgence. The Psychological Record, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-021-00456-z

Houck, E. J., Dracobly, J. D., & Baak, S. A. (2023). A practitioner’s guide for selecting functional communication responses. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 16, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00705-9

Kazdin, A. E. (1980). Acceptability of alternative treatments for deviant child behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13, 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1980.13-259

Kunnavatana, S. S., Wolfe, K., & Aguilar, A. N. (2018). Assessing mand topography preference when developing a functional communication training intervention. Behavior Modification, 42(3), 364–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517751437.

Kurtz, P.F., Leoni, M. & Hagopian, L.P. (2020). Behavioral approaches to assessment and early intervention for severe problem behavior in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Pediatric Clinics, 67(3), 499-511.

Livingston, C. P., DeBrine, J. E., Melanson, I. J., Kwak, D., & Tomasi, B. (2024). Comparison of caregivers’ and children’s preference for mand topography during functional communication training. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09973-5

MacNaul, H., Cividini-Motta, C., & Randall, K. (2024). Differential reinforcement without extinction: An assessment of sensitivity to and effects of reinforcer parameter manipulations. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 546. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070546

Ringdahl, J. E., Falcomata, T. S., Christensen, T. J., Bass-Ringdahl, S. M., Lentz, A., Dutt, A., & Schuh-Claus, J. (2008). Evaluation of a pre-treatment assessment to select mand topographies for functional communication training. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2008.06.002

Ringdahl, J. E., Berg, W. K., Wacker, D. P., Crook, K., Molony, M. A., Vergo, K. K., Neurnberger, J. E., Zabala, K., & Taylor, C. J. (2018). Effects of response preference on resistance to change. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 109(1), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.308

Tiger, J. H., Hanley, G. P., & Bruzek, J. (2008). Functional communication training: A review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391716

Winborn-Kemmerer, L., Ringdahl, J. E., Wacker, D. P., & Kitsukawa, K. (2009). A demonstration of individual preference for novel mands during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(1), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2009.42-185