Guest Blog Authored by: Anna Ingeborg Petursdottir, Ph.D., BCBA-D

Dr. Anna Ingeborg Petursdottir is an associate professor in the Behavior Analysis program at the University of Nevada, Reno. She directs the Language and Learning Lab (3L), the mission of which is to advance knowledge of the operation of basic behavioral processes in human language and cognition, and to translate that knowledge into potential applications in education, training, and language intervention. Anna is a former editor-in-chief of The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, and has served major journals and professional organizations in our field in numerous ways. As a young child, Anna wondered why people kept calling the sky blue, when to in reality, it always looked white to her when she looked up at the dense cloud cover over her native Iceland.

What is the Color of the Sky? Reasons for Answering “Blue”

Verbal behavior can involve simple verbal responses controlled by isolated stimuli, such as saying “ball” as a result of seeing a ball; a typical introductory example of a tact. However, we often respond verbally to multiple sources of stimulation at the same time. If I point to the sky and ask, “What color”? your response “blue” may be evoked simultaneously by the sky that’s being pointed to (tact control) and the question “What color?” (intraverbal control). Or if I ask “What is the color of the sky?” when the sky is not currently visible, your response “blue” may be controlled intraverbally by both “What color” and “the sky”. In this excellent post, Kodak et al. (2024) provided guidance to practitioners for teaching children to respond effectively to antecedent stimuli like these. They also called for applied researchers and practitioners to continue to develop and refine effective procedures for teaching these skills, given the ubiquity of control by multiple stimuli in mature verbal repertoires.

So Many Terms!

If you are new to the topic of complex verbal skill acquisition, you may be overwhelmed by the many terms used in the literature to describe verbal responses controlled by multiple antecedents. In research on intraverbal responding, for example, you’ll find references to verbal conditional discriminations (Sundberg et al., 2011), multiply controlled intraverbals (Kisamore et al., 2016), convergent intraverbals (DeSouza et al., 2019), and intraverbal responses under complex stimulus control (Haggar et al., 2018) or compound stimulus control (Cariveau et al., 2022). Do they all mean the same thing, or is there a difference? That’s what I hope to clarify in this post. The intent is not to provide either in-depth or practically actionable information, but rather, to help researchers and practitioners orient to the literature and its vocabulary. I will focus on intraverbal responding, but the information should also be applicable to other situations (see e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2022). Without further ado, what is going on when a stimulus like “What is the color of the sky?” evokes a response like “blue”?

Photo by Guilherme Garcia on Unsplash

Is It Complex?

Noting that complex discrimination was not a technical term in behavior analysis, McIlvane (2013) distinguished it from a simple discrimination by specifying that it involves control by two or more separable stimulus elements. However, McIlvane’s definition has not been widely adopted, and the “complex” descriptor continues to be applied to various forms of stimulus control that may or may not fit the definition. If you use this term, you need to specify what you mean.

Is the Question a Compound Stimulus?

A compound stimulus can be defined descriptively as a stimulus comprising two or more parts or elements, regardless of what the function of these elements might be. In one sense, most stimuli can be thought of as compounds: even a stimulus as simple as a light in an operant chamber contains different elements such as brightness and spatial location. In research, however, the term is typically used to describe the simultaneous presentation of two stimuli that can also be presented separately. In basic research, common examples include a light and a sound, or two visual images presented side by side. “What is the color of the sky?” seems to qualify as a compound in that it consists of elements that can be presented separately (e.g., “What is the color of” [hereafter “color”] and “the sky”). Although some definitions of a compound stimulus specify that the elements must be presented simultaneously, other sources (e.g., Looney et al., 1977) clearly allow for one element to be presented slightly ahead of the other, as when the question is presented vocally.

Is It Compound Stimulus Control, Then?

A compound stimulus can control behavior in different ways. The response “blue” to “What is the color of the sky?” could be controlled selectively by a single stimulus element (e.g., “color” or “the sky”). Alternatively (and practically speaking, hopefully), both elements may play a role. If “What is the color of the sky?” evokes “blue” but other compounds with overlapping elements (e.g., “What flies in the sky?” and “What is the color of grass?”) evoke different responses or no response at all, it suggests both elements are necessary to evoke “blue.” However, there are several possible reasons why both are necessary: We may be looking at configural, direct elemental, or hierarchical elemental control.

The terms compound stimulus control and compound discrimination have been used in the literature on intraverbal responding (e.g., Eikeseth & Smith, 2013; Sundberg, 2016) in a way that usually seems to describe direct elemental control but is sometimes more consistent with configural control. Because the use of these terms is not completely consistent, I try to use “compound” only to refer to the composition of stimuli and not to their possible functions.

How About Multiple Stimulus Control?

As noted above and clarified further below, there are several reasons why both “color” and “the sky,” might be necessary to evoke the response “blue.” A case could be made for saying that in all of these cases, the response is multiply controlled in the sense of being controlled by the presentation of multiple stimuli. That said, I recommend using the term multiple control cautiously for two reasons: First, outside of the verbal behavior literature (e.g., in functional assessment), it often refers to behavior maintained by more than one source of reinforcement. In verbal behavior, that’s not usually what we want to convey, so it may be necessary to specify that you are talking about antecedent control. Second, multiple control plays an important role in Skinner’s (1957) analysis of verbal behavior, but in that context, (a) involves two subtypes, only one of which (convergent control; Michael et al., 2011) has to do with control by compound stimuli, and (b) in the case of that subtype, tends to be used to describe responses to novel compounds, specifically. Basically, if you describe the response “blue” as multiply controlled by “color” and “the sky,” it is best if you also specify whether you are saying it is a multiply controlled operant resulting from reinforcement in the presence of the entire compound, or that it is a product of convergent multiple control, discussed further here.

Four Ways a Compound Stimulus Can Control Behavior

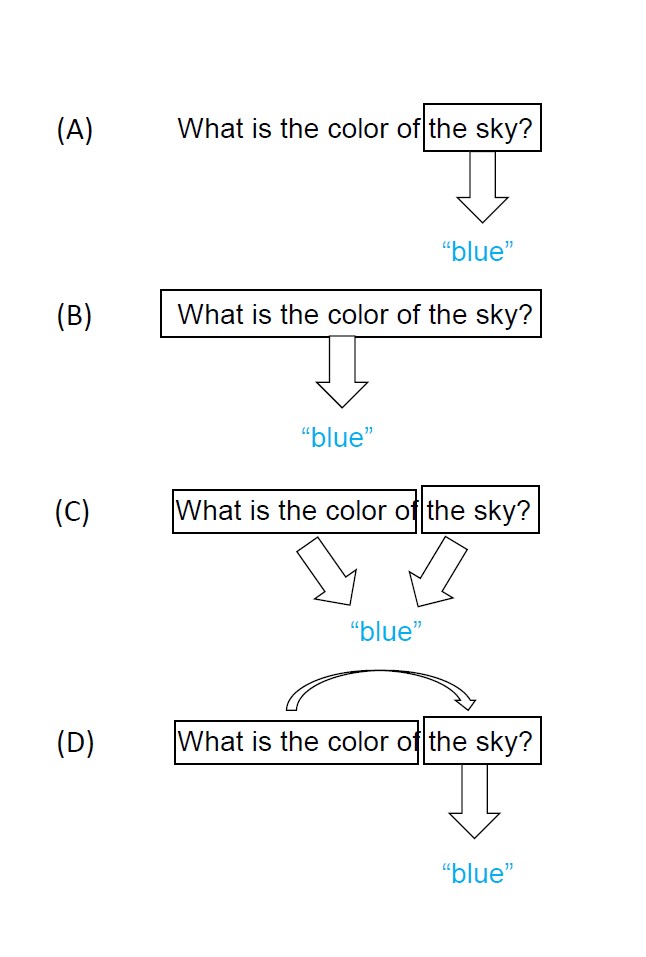

Diagram created by the author.

This diagram illustrates four ways in which a verbal compound stimulus like “What is the color of the sky?” might control the response “blue” (see diagram). The text below contains a more detailed explanation of each scenario, along with relevant reinforcement histories.

(A) Selective Control by a Single Element

A learner may reliably respond “blue” to “What is the color of the sky?” but upon further examination, we may find the response is controlled exclusively by “the sky” without “color” playing any role (or vice versa). As a result, the learner may incorrectly respond “blue” to other compound stimuli like “What flies in the sky?” and “Where is the sky?” As shown in a recent study (Cariveau et al., 2022), reinforcing intraverbal responding in presence of compound stimuli may result in selective control when the only discrimination requirement involves non-overlapping compounds, such as “Name an animal that lives in the ocean” (which does not share key elements with the first compound). The term stimulus overselectivity has sometimes been used to describe this possible outcome. Outside the verbal behavior literature, selective control is well-known in both operant and Pavlovian conditioning, and may be attributed to one stimulus being more salient than the other (termed overshadowing) or to prior learning histories (blocking). Explicitly training discriminations between sets of overlapping compounds (e.g., “What is the color of the sky?”, “What is the color of grass?”, “Where is the sky?”, “Where is grass?”) may prevent this outcome, but many students struggle with such discriminations, requiring intervention.

(B) Configural Control

Configural control is another possible outcome of reinforcing a response in the presence of a compound stimulus. In configural control, the response “blue” is controlled by the stimulus “What is the color of the sky?” as a whole, instead of by its elements playing independent roles. In this case, we might see that a different configuration of the same or similar elements, such as “When you look up at the sky, what color do you see?” fails to evoke the same response. Training discriminations of overlapping compounds may reduce the probability of configural control, but may not completely eliminate it, as each compound could still end up functioning simply as a single stimulus. Practically speaking, in a procedure like matrix training (see Frampton & Axe, 2022), recombinative generalization to untrained cells in the matrix might fail to occur if initial training has produced configural instead of elemental control.

(C) Direct Elemental Control, and Relation to Convergent Control

In direct elemental control, each element independently exerts discriminative control over the response. That is, both “color” and “the sky” may evoke the response “blue” even when presented without the other element; for example, “Name a color” and “Tell me something about the sky” might evoke “blue” along with other responses. Direct elemental control can be an outcome of reinforcing a response in the presence of a compound stimulus, but it can also be an outcome of reinforcing it in the presence of each element in isolation. That is, “blue” may never have been reinforced in the presence of “What is the color of the sky?” but may have been reinforced in the presence of both “color” and “the sky.” In research of stimulus control, when the same response is reinforced separately in the presence of two different stimuli in isolation, presenting the two stimuli together in compound tends to evoke a stronger response (e.g., higher rates of responding) than each stimulus in isolation; this additive effect of two discriminative stimuli is referred to as summation.

In convergent multiple control (Michael et al., 2011), the presentation of two stimuli that independently control the same response increases the probability that a specific response will be emitted, as opposed to responses that might be controlled by the individual elements, such as “red” and “airplane.” Therefore, convergent control is essentially a special case of direct elemental control that results from a history of reinforcement in the presence of each element, rather than due to reinforcement in the presence of the compound. Summation then explains (according to Skinner, 1957) why the presentation of the compound increases the probability of the response “blue” over “red” and “airplane” (see Oliveira et al., 2024, for an experimental demonstration). Alternatively, instances of convergent control might occur due to joint control (Lowenkron, 1998) instead of summation, but this is a nuanced distinction that will not be discussed further here.

(D) Hierarchical Elemental Control, and Relation to Conditional Discriminations

In hierarchical elemental control, each element of the compound also plays an independent role, but unlike direct elemental control, different elements have different functions. Only one may function as a discriminative stimulus for the response, whereas the other modulates the effect of the discriminative stimulus but does not directly control the response. For example, the presentation of “What is the color of” may result in “the sky” (the discriminative stimulus) evoking the response “blue”, whereas the presentation of another stimulus like “What flies in” may result in “the sky” evoking a different response, such as “airplane.” Alternatively, “color” could be the discriminative stimulus, and presentation of stimuli like “the sky” and “grass” might modulate the evocative effect of that stimulus, determining if it evokes “blue” or “green.” Hierarchical control is a possible outcome of systematic reinforcement of overlapping discriminations (e.g., responding “blue” to “color” is reinforced only when “the sky” is present and not when “grass” is present). Research on occasion setting (see Leising et al., 2025) focuses on hierarchical control and how it may be distinguished from direct elemental control.

If this reminds you of the term conditional discrimination, it is not a coincidence. In the verbal behavior literature, definitions of verbal conditional discriminations (e.g., Sundberg, 2016) tend to be consistent with hierarchical control in which one stimulus alters the function of another. In the stimulus control literature more generally, conditional discriminations were historically often defined in this manner as well. In more recent behavior-analytic sources, however, a conditional discrimination is usually defined in terms of the reinforcement contingency that produces it: It is a discrimination in which reinforcement of a response to one stimulus is conditional on the presence of another stimulus (e.g., Cooper et al., 2020). This definition does not specify the resulting stimulus functions, as such contingencies can potentially produce not just hierarchical but also direct elemental or configural control. Further, some have argued that most conditional discriminations involve direct rather than hierarchical elemental control (McIlvane, 2013). Given this ambiguity, perhaps the term verbal conditional discrimination is best used as an umbrella term to describe all outcomes of conditional discrimination training, regardless of whether the resulting stimulus functions are most consistent with (B), (C), or (D) above.

Identifying Controlling Relations

Scenario (A) is practically important to distinguish from (B), (C), and (D), and relatively straightforward to identify by testing responses to overlapping compounds. By contrast, (B), (C), and (D) are harder to tell apart conclusively based on the speaker’s behavior, which has resulted in various theoretical debates that will not be detailed here. It is possible that, for many intents and purposes, it is not all that important to distinguish between them in applied settings. As long as a learner responds to different compound stimuli as expected by the verbal community, perhaps we don‘t care that much if the functions of the stimulus elements are most consistent with (B), (C), or (D); that is, perhaps these distinctions are more important in theory than in practice.

Nonetheless, it may be instructive to speculate on which type of control might be involved in different instances of verbal responses to multiple stimuli, based on the typical practices of the verbal community, and how and whether our approaches to teaching might differ depending on the answer. For example, in the case of “What is the color of the sky?” evoking the response “blue,” it seems plausible that for most speakers, each element may also independently control that response: If we ask the speaker to quickly say the first ten words that come to mind when they hear “color” it is likely that “blue” would be among them, and the same might be true if we asked for five words in response to “the sky.” In other cases, other forms of control might be more plausible. For example, in United States culture, responding “blue” to “red, white, and …” (Sundberg, 2016) would probably be an instance of configural control, because although both “red” and “white” might independently evoke “blue,” they would also be expected to exert convergent control over other responses like “green” and “yellow.” The fact that “blue” overwhelmingly occurs may suggest that the stimulus as a whole is not simply the sum of its parts. In yet other cases, hierarchical control may be more likely. For example, addition of the stimulus element “with” to other stimuli like “What do you sweep?” and “What do you write?” may change the speaker’s response from “the floor” to “a broom” and from “a story” to “a pen” (see Haggar et al., 2018); yet it seems implausible that “with” by itself might control either one of these responses and more plausible that it alters the function of the remainder of the stimulus.

On a Final Note: Novel Compound Stimuli and Novel Contingencies

Given the almost infinite ways in which verbal stimuli can combine, it is likely that we often encounter novel verbal stimulus compounds. As previously noted, convergence of direct elemental control may result in emission of an appropriate response (i.e., one that the verbal community will reinforce): We may respond “blue” because of the convergence of control by “color” and “the sky.” In other cases, we may simply respond individually to each element, for example, the novel compound “Where are Oslo and Athens?” might evoke “Oslo is in Norway and Athens is in Greece.” And in yet other cases, although the verbal stimulus compound is novel, we may have acquired relevant discriminations of compounds involving stimuli that belong to the same equivalence classes as the verbal stimuli (Devine et al., 2022). But some compounds may not contain any elements that directly control the appropriate response, as in “What is 738 divided by 18?” And some compounds may be quite familiar, but the appropriate response may differ from one occasion to the next, as in “Where did you go on vacation last year?” I refer the reader to Palmer (2016) for a discussion of how we may end up responding effectively in these kinds of situations. The bottom line is, both familiar and novel combinations of stimuli can affect verbal behavior in many different ways! To build effective verbal repertoires, we may ultimately need to attend not only to reinforcing conditional discriminations and building prerequisites for convergent control, but also to building skills that permit effective responding when these are insufficient.

References

Cariveau, T., Brown, A., Platt, D. F., & Ellington, P. (2022). Control by compound antecedent verbal stimuli in the intraverbal relation. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 38, 121-138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-022-00173-w

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson

DeSouza, A. A., Fisher, W. W., & Rodriguez, N. M. (2019). Facilitating the emergence of convergent intraverbals in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(1), 28-49. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.520

Devine, B., Carp, C. L., Hiett, K. A., & Petursdottir, A. I. (2016). Emergence of intraverbal responding following tact instruction with compound stimuli. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 32, 154-170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-016-0062-6

Eikeseth, S., & Smith, D. P. (2013). An analysis of verbal stimulus control in intraverbal behavior: Implications for practice and applied research. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 29, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393130

Frampton, S. E., & Axe, J. B. (2022). A tutorial for implementing matrix training in practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 23(16), 334-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00733-5

Haggar, J., Ingvarsson, E. T., & Braun, E. C. (2018). Further evaluation of blocked trials to teach intraverbal responses under complex stimulus control: Effects of criterion-level probes. Learning and Motivation, 62, 29-40.

Kisamore, A. N., Karsten, A. M., & Mann, C. C. (2016). Teaching multiply controlled intraverbals to children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(4), 826-847. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.344

Kodak, T., Brown, B., & Duszynski, B. (2024). How to teach verbal conditional discrimination: A practical framework. Verbal Behavior Matters. https://behavioranalysisblogs.abainternational.org/2024/12/04/how-to-teach-verbal-conditional-discrimination-a-practical-framework/

Leising, K. J., Nerz, J., Solorzano-Restrepo, J., & Bond, S. R. (2025). Are you studying occasion setting? A review for inquiring minds. Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews, 20, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.3819/CCBR.2025.200002

Looney, T. A., Cohen, L. R., Brady, J. H., & Cohen, P. S. (1977). Conditional discrimination performance by pigeons on a response-independent procedure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 27(2), 363-370. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1977.27-363

Lowenkron, B. (1998). Some logical functions of joint control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 69(3), 327–354. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1998.69-327

McIlvane, W. J. (2013). Simple and complex discrimination learning. In G. J. Madden, W. V. Dube, T. D. Hackenberg, G. P. Hanley, & K. A. Lattal (Eds.), APA handbook of behavior analysis, Vol. 2. Translating principles into practice (pp. 129–163). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13938-006

Michael, J., Palmer, D. C., & Sundberg, M. L. (2011). The multiple control of verbal behavior. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393089

Oliveira, J. S. C. D., *Cox, R. E., & Petursdottir, A. I. (2024). Summation in convergent control over selection-based verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 40(2), 326-344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-023-00194-z

Palmer, D. C. (2016). On intraverbal control and the definition of the intraverbal. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 32(2), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-016-0061-7Rodriguez

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Sundberg, M. L. (2016). Verbal stimulus control and the intraverbal relation. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 32, 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-016-0065-3

Sundberg, M. L., & Sundberg, C. A. (2011). Intraverbal behavior and verbal conditional discriminations in typically developing children and children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393090