Normally I like posts that lean into scientific principles and hard data; that present tidy, linear arguments; and that get to the point and provide a clear take-home message. This isn’t that kind of post. It’s too long, it’s subjective, and it rambles. And the title is kind of misleading. Sorry! I tried to make the post conform to the usual specifications, but it insisted on being what it is. Which, in a way, is EXACTLY what this post is about.

Meet Jeremy

Jeremy, an on-the-spectrum IT professional at a major corporation, loves the TV series Game of Thrones. I mean a LOT. Jeremy has watched every GOT episode multiple times and and can tell you everything that happens in every one of them. Verbatim. Given even a hint of opportunity, he probably will tell you, because talking about GOT is almost as much fun for Jeremy as watching GOT. There are only a few things that Jeremy likes as much as GOT, including baking (he volunteers weekend mornings at a local bakery) and singing (he performs in community musical theater productions).

Once I asked Jeremy if he would want to live in the GOT universe, and, after pointing out that this is impossible (because, Tom, GOT is fiction, and you can’t actually go into fiction, even if you want to, because it’s not real), he provided an answer that was unexpectedly complex. Yes, he would enjoy being in that world, with one major caveat. Most of the show’s primary characters are motivated by greed and ambition in ways that Jeremy simply is not. Rather than orchestrating world domination, Jeremy would prefer to bake scones for the villagers and sing in the Faith of the Seven church choir.

In considering how Jeremy is different from GOT’s movers and shakers, we can assume part of the answer: Those people grew up immersed in a culture where the pursuit of money and power is a big deal. You might say these people learned, from an early age, that this is stuff you should want.

Should Rules

Acceptance and Commitment Theory (ACT) assumes that there is a dark side to the verbal precociousness that separates humans from other species. For us, words can substitute for shaping, so we can learn simply from being told. That’s rule governed behavior. Rules can be either beneficial or harmful, and in the ACT framework rules become harmful when they control behavior that doesn’t support well-being.

As a university professor I meet tons of students whose life plan is constructed from rules they inherited from other people. One young woman whose relatives were all medical professionals spent seven years as an undergraduate, in pursuit of becoming a doctor, eventually flunking organic chemistry five times. One school psychology graduate student’s eyes would go dead every time she had to meet with children. In these cases, doing what a “should rule” specified didn’t make the individuals happy, but yet they persisted. Metaphorically, their rules told them they would be bad people, or professional failures, if they did not. It’s this clash between rule governed behavior and natural reinforcers that ACT says is at the core of human suffering (for previous posts on this theme, see here and here).

One really interesting thing about people like Jeremy is that they often don’t care what some “should rule” says. Jeremy is into GOT, baking, and singing. So Jeremy pursues GOT, baking and singing.

Sure, this means risking others’ disapproval. But when you meet Jeremy for the first time, he would rather check whether you want to talk about GOT than miss an opportunity to talk about GOT. If you don’t want to talk about GOT, and even if you decide he’s a bit obsessive or strange for wanting this, so be it. That’s the cost of pursuing reinforcers — you gotta take your shot. And since some people do want to talk about GOT, there’s an intermittent schedule, and you can’t win if you don’t play.

Jeremy recognizes that some people value different things than he does, things that society says are important, like money and power. But he’s never internalized these things as “should rules,” and he would absolutely, positively be perfectly happy as a singing baker in a GOT universe where everyone else is consumed by violent social climbing.

Inner Voices

I want to be clear: I’m not saying people with autism (at least highly verbal ones) don’t have an “inner voice” like the rest of us, that little megaphone that privately spouts “should rules.” I couldn’t find much research on this, but the gist of what I’ve read is that for many people on the spectrum that little voice inside the head is just as active as for anyone else. It may even be as likely to repeat “should rules.” However, there appear to be some differences, so let me propose one based on my own casual experience: In neurotypical individuals, the inner voice is a font of socially-mediated should rules, as ACT asserts, whereas in ASD individuals the rules are more likely to be self-derived (though see the Postscript).

In this regard, part of the joy of Jeremy is that he likes what he likes, and it doesn’t matter to him if other people don’t get jacked about the same things. Ditto for Andrew, an on-the-spectrum library worker who totally digs airplanes (particularly certain Cessna and Boeing models).

“Should rules” say to not get too nerdy about any one thing, but joy might argue otherwise.

I wish a lot of my college students felt free to be more like Jeremy and Andrew, to simply like what they like. Their behavior shows that they don’t like medicine, or children, or whatever, but they are locked into behavior patterns that surround them with exactly that. Metaphorically, to be happy, these people need to bake more scones.

Digression: About That “Next Step in Evolution”

I used that in the title, so I’d better say something about it before moving on. The idea that autism might represent a next phase of human evolution has been around for almost as long as I’ve been paying attention. Andrew’s mom, a mental health professional, has been saying this for 30 years, in part because the rapidly-increasing prevalence of autism suggests there may be some kind of advantage to being on the spectrum. The “next step” hypothesis was spelled out most clearly in Simon Baron-Cohen’s book The Pattern Seekers: How Autism Drives Human Invention (read a review here). Baron-Cohen argues that changes in cognitive architecture, originating perhaps 70,000 years ago, gave humans the capacity for enhanced attention to detail and what nowadays we call restricted interests. This, in turn, gave selected humans an advantage in solving problems that affect humans in general, making neurodiversity of value to the species as a whole.

Let’s take it at face value that evolutionary processes have yielded a distribution in which some individuals are more inclined to pursue restricted interests. What if the change that facilitated this was a tweak to verbal behavior systems? Bear with me here. Language probably arose 100,000 to 200,000 years ago, in creatures who were very dependent on group cohesion for survival. Humans, after all, are physically weak individually, but capable of enhanced accomplishments when working collectively. Oh, and of course you can’t pass your DNA along if you aren’t part of a breeding group. So, it seems likely that promoting group cohesion was a critical early function of language. Put another way, language helped to assure that you behaved like others in the “tribe” that you cared about retaining your membership. “Should rules” would be an important part of that by reducing reliance on gradual shaping of the required behaviors.

Now, socially-mediated “should rules” can help individuals conform to group norms, but conformity is the opposite of innovation. Once the capacity for rule-governed behavior was around for a while, it’s just possible that groups with greater variation in this ability (i.e., some individuals were tightly rule-bound, while other, not so much) prospered especially well. Maybe some individuals retained rule-governed behavior generally but were not as sensitive to social influences than others. They were free to pursue restricted interests and as a result just maybe could solve things that other humans couldn’t. That would accomplish pretty much everything Baron-Cohen says happened 70,000 years ago, and it would give the group enough of an advantage that across generations its variation would persist, even grow.

Are there disadvantages to nonconforming? Sure, especially if your restricted interests fall upon things that are dangerous or have no bearing on group success. If intellectual limitations come along for the ride, as can happen on the spectrum, well, that’s an issue. And if an individual’s social sensitivity is sufficiently muted, perhaps language doesn’t develop at all, or perhaps the individual doesn’t really function as a member of the tribe.

All of that’s true, but keep in mind that evolutionary adaptations don’t have to be 100% beneficial — for instance, sickle cell trait confers resistance to deadly malaria but also can produce fatigue, pain, and organ damage. In natural selection terms, all that’s required for a trait to be preserved across generations is that (a) on average it confers advantages to the group, and (b) the individual reproduces. Clause (a) seems plausible, and if you work with kids on the spectrum and their parents you know that quite a few adults on the spectrum reproduce.

Joy is Irresistible

OK, make of the preceding what you will — I totally winged it on that explanation, and I’m not sure if it really holds up to scrutiny. It’s a thought exercise that I’m unsure I believe myself (though it dovetails nicely with research suggesting that being on the spectrum buffers people against the adverse effects of social comparisons). So let’s go back to just being descriptive. What’s refreshing about people like Jeremy is how unencumbered they are by socially-mediated “should rules.” They know what makes them happy and, circumstances permitting, they go after that.

You might think that behavior which is, in actuarial terms, atypical would automatically come across as strange, perhaps putting at risk an individual’s place in the “tribe,” but that’s not necessarily the case. People can feel drawn to the joy that comes from pursuing your joy. Here’s an example.

Four times a year Andrew, who you met above, hosts an “Autism Flight” in which he sort of simulates a commercial airline flight. Andrew wears an airline pilot’s uniform and his best friend, Bill, is the co-pilot, and together they take 50 to 75 volunteers on an imaginary trip through the friendly skies. There are gate announcements and boarding protocols. “Passengers” stand behind Andrew and Bill in something like a seating pattern while uniformed flight attendants assist passengers, assure order, and, of course, pass out in-flight snacks. During the flight everyone marches in formation around the field — this can take an hour or more — while Andrew reproduces every word a pilot would speak during a real flight, from preflight checks to chatter with air traffic controllers. Although some of attendees are other people on the spectrum, a surprising number of passengers and “airline personnel” are random people from the community who’ve had some contact with Andrew over the years and found his enthusiasm for planes to be infectious. I’d go so far as to say that many of these people, in their own lives, never experience the kind of unadulterated joy that Andrew gets from planes, and they’re drawn to Autism Flight to experience this vicariously.

If the rest of us were less encumbered by socially-mediated, conformity-focused “should rules,” we might find more of our own joy and, as Autism Flight illustrates, even have more of a positive effect on other people.

It’s interesting to note that, at some level, popular culture understands the conflict between socially-mediated “should rules” and personal fulfillment — even if individual people struggle with this. In countless teen films, for instance, the protagonist learns difficult careful-what-you-ask-for lessons from pursuing what the popular kids have (see “Mean Girls” — c’mon, Cady, ditch those Plastics and date the improbably handsome mathlete boy!). In maybe 50% of Hallmark Channel movies, someone has to discover how chasing career success has undermined their wholesome small-town values. These are cinema tropes, sure, but we wouldn’t tune in if a trope held no value for us.

In Praise of Neurodiversity, Although…

The medical model of intervention that ABA has embraced from its infancy portrays atypical behavior as something to be corrected — which is unambiguously true in some instances where there’s risk of harm to the individual or other people (e.g., severe self-injury). But there are nuances and gray areas, and overlooking them has sometimes gotten our discipline into trouble — including, in recent years, as neurodiversity advocates painted us as fascist diversity-suppression stormtroopers.

People like Jeremy and Andrew, and a book like The Pattern Seekers, remind us of the better angels of a neurodiversity movement that people in behavior analysis might be inclined to view in adversarial terms. I mean, I get it. It’s hard to feel warm and fuzzy about people who excoriate your entire discipline and distort the difficult, socially-important work that you do. But neurodiversity advocates have a point: There can be individual and even societal benefits to nonconformity, and maybe we behavior analysts don’t celebrate that enough.

Neurodiversity advocates stress that, as expressed by the publisher of a children’s book series (The Millicent Quibb School of Etiquette for Young Ladies of Mad Science; written by Saturday Night Live alum Kate McKinnon): “Being weird is exactly what makes you wonderful.” The irony is that most applied behavior analysts who work in autism need no reminder of this — in fact, many were drawn to autism in the first place precisely by a special affinity for their clients’ outsized individuality. But neurodiversity advocates see in us what they see, and their objections to ABA suggest that we don’t let our appreciation of client individuality shine through often enough in how we describe our Very Rigorous Protocolized Evidence-Based Interventions.

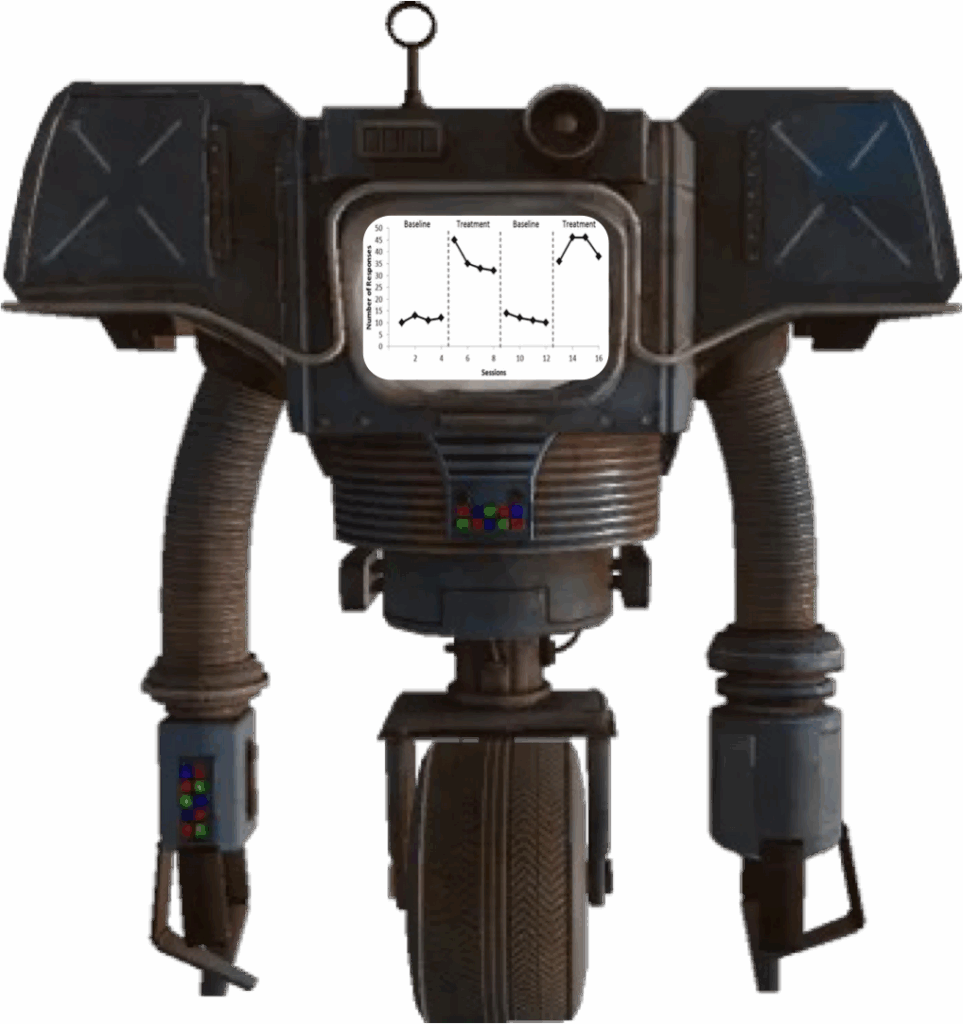

In recent decades we behavior analysts have learned a lot about relating our discipline’s story in scientific terms. The scientific community told us that an A-B-A-B graph doesn’t count as persuasive evidence of intervention effectiveness, and to be more persuasive we’ve begun learning the language of randomized controlled trials and effect size and meta-analysis. But to people who aren’t scientists, of course, that language is just as unintelligible as behaviorese, and just as off-putting and dispiriting. As a result, when we read what ABA’s critics say, we scarcely recognize ourselves in the critique, for instance:

This practice [ABA], grounded in scientific positivist assumptions and the biomedical model of disability, continues to legitimate segregation and inequality and justify a dual system of special education. Demonstrating the socially constructed nature of difference/deviance, labeling deviance theory has played a crucial role in challenging this orientation, serving as one of the key conceptual foundations for the disability and inclusive movements. (Fitch, 2010, p. 18)

And

ABA, through the scientific lens of humanistically decontextualized outcomes-based evidence-basis, harnesses a powerful rhetorical device by offering parents not a choice between a happy child or an unhappy child, but rather a hopeless abnormal child, or a hopeful normal one. As a result, the legitimacy of the medical model of disability is both preserved and propagated, situated squarely as the frame upon which parents are implored to make decisions about the ‘‘treatment’’ of their children. (Shyman, 2016, p. 363)

And

What, in the end, are you fighting for: Normal? Is normal possible? Can it be defined? …AND is normal superior to what the child inherently is, to what he aspires to, fights to become, every second of his day? Normal in terms of what, and by what sacrifice? (Kephart, 1998, p. 11)

From the perspective of the neurodiversity movement, it’s a good thing neither Jeremy or Andrew experienced ABA therapy that would have stripped them of their uniqueness. Except…

Both Jeremy and Andrew actually had a ton of ABA therapy when they were little Why? Because Andrew had hair-trigger tantrums, engaged in self-injury, and broke more than few bystander fingers (at age 7, he was in fact removed by security from the very library where he works today). Jeremy was detached and all but unreachable. If you’ve seen that early segment of the famous Lovaas film where a little girl sits alone on the floor, looking at her fingers and spinning shiny objects, over and over and over and over, then you’ve basically met young Jeremy.

Original Voices

I don’t think enough people know about Jeremies and Andrews, not their whole stories anyway, because we behavior analysts have some work to do when it comes to telling those stories. As the late Ronnie Detrich (2018) observed:

From the very early days of behavior analysis the mission has included “better living through behaviorism” with the goal of bringing behavioral technology to every aspect of human activity (e.g., Skinner, 1948)… In their seminal paper on applied behavior analysis, Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968) offered the following observation about dissemination: “…It is a fair presumption that behavioral applications, when effective, can sometimes lead to social approval and adoption” (p. 91). Yet, the general conclusion among contemporary behavior analysts is that the social approval and adoption rate has been disappointingly slow….We built a better mousetrap but the world did not beat a path to our door. (p. 541)

The problem, as Ronnie pointed out, is that, “Scientists in general and behavior analysts in particular may not have the necessary repertoire to be effective storytellers” (p. 547). [Duh. Ever sat through a convention presentation? Most of them are snoozers even for people with built-in interest in the topic.]

Until we get better at telling ABA’s stories, perhaps we can get an assist from verbally capable people like Jeremy who’ve benefitted from ABA. Not too long ago Jeremy was “seated” next to me on an Autism Flight, so we had some time to kill. I asked him about his younger self, and he told me this:

When I was young, I did a lot of stimming, When I was stimming I didn’t notice anything else. I loved the intricate patterns in how I moved my fingers and I could look at that all day. You could have banged a gong next to my head and that wouldn’t have registered.

Once I was stimming less I began to notice other things. Like music. Intricate patterns of notes fascinated me, and one of the best days of my life was when I discovered I could make those same patterns with my voice! Stimming used to be all that most people knew about me because it’s all I showed them. Now they can see me on stage performing in “Oklahoma!”

I haven’t really changed that much. The patterns of finger movements I made, not many people would be able to do that. Now the patterns I make with my vocal chords, most people can’t do that either. I’m a good baker and computer coder too. I’m different because I found more things to love, but I’m still me. One thing I have learned is if showing other people what makes me happy makes them happy, that makes me extra happy. I never knew that before and if I was stimming all the time I would still not know that.

Neurodiversity advocates fear that ABA will destroy what makes people unique. Jeremy says ABA opened his eyes to new ways of expressing his uniqueness. Stories like that are worth telling. Why aren’t we doing more to let interesting people like Jeremy tell them?

Postscript

About my supposition that rule governance might work differently on and off the spectrum: There’s some research from outside of behavior analysis suggesting a positive correlation in persons on the spectrum between theory of mind and what behavior analysts would call rule governed behavior. But that apparently applies only to higher-IQ individual on the spectrum. If this is correct, well, I told you the whole business was complicated. I’m not inclined to put too much stock in these results, however, because the research employed traditional theory of mind tasks that may not measure what they’re claimed to; and because the procedure focused on a very constrained form of rules. Within behavior analysis, it appears that most of the existing research focuses on teaching low-verbal individuals to follow verbal rules. That’s also of potentially limited relevance to my musings.

Perhaps consider a descriptive account of rule-governance by highly verbal children on the spectrum. From the abstract:

The article explores how high-functioning children with autism navigate in the social world, specifically how they orient in the realm of norms and standards…. High-functioning children with autism can actively engage in discourse about norms and transgressions in an initiatory capacity, thereby displaying a mastery of social rules as a guide for appropriate conduct and interpretation of others’ behavior…. Prior courses of action constitute for the autistic children the fundamental source for reaching an understanding of the normative mechanics of everyday life, and subsequently for constructing their own lines of conduct and themselves as moral agents.

Sounds like self-derivation of rules. FWIW.