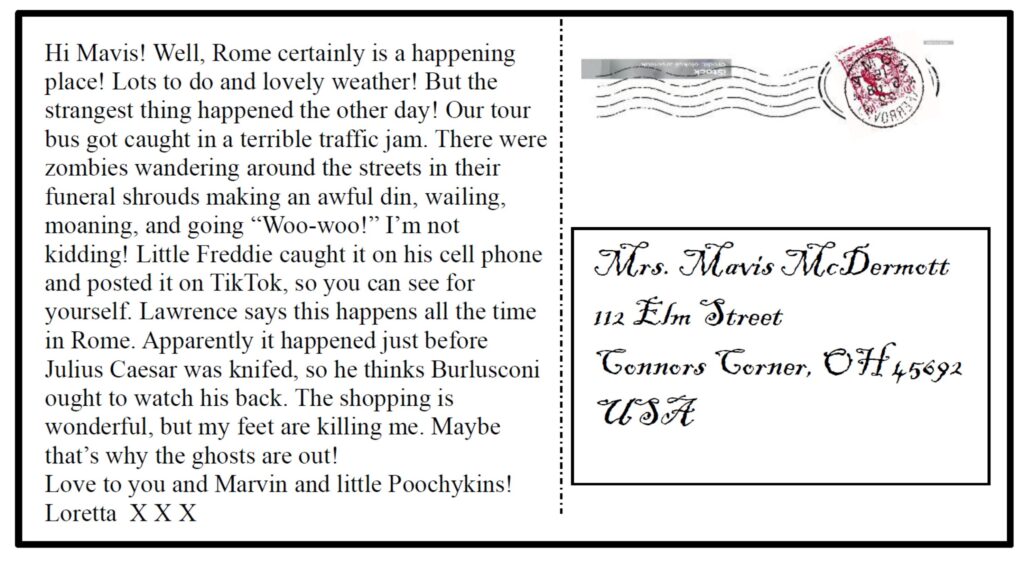

Apparently, Lawrence was right. Visitations by zombies to the streets of Rome has happened before. Here’s how Shakespeare reported the “Caesar incident” in the opening scene of Hamlet:

In the most high and palmy state of Rome,

A little ere the mightiest Julius fell,

The graves stood tenantless, and the sheeted dead

Did squeak and gibber in the Roman streets.

It’s unlikely that the postcard to Mavis will be read by high school students all over the world four centuries from now, for Lorretta lacks a talent for putting words together in unforgettable ways, a gift that Shakespeare displayed in nearly every line of his plays. Thoreau once said, of venerable monuments, “When the thirty centuries begin to look down on it, mankind begins to look up at it,” but I submit that the difference between the play and the postcard is not one of antiquity, or of the reputations of its authors; Shakespeare had an uncanny knack for putting pairs of words together, X-and-Y, that stick in the ear, apparently for centuries. What was his secret?

The state of Rome is not just most high, it is most high and palmy. Why palmy? What does palmy even mean? I’ll bet you don’t know. Well, according to my desk-top dictionary, it means flourishing, which certainly fits the context. But why does palmy mean flourishing? The Oxford English Dictionary traces the meaning back to—you guessed it—Hamlet. So the Bard, chewing on the end of his quill, trying to think of just the right way of saying back in the day, when life was good, settled on most high and palmy, thereby coining a word for the ages and a phrase to puzzle school children. (First-in-print doesn’t necessarily imply coinage; perhaps he picked it up from a fellow patron of the White Hart Inn, but even so, he was surely the first to use it to describe the happy state of ancient Rome.) He apparently knew that the audience would impute a meaning to the word required by its context, and it suited the meter and cadence of his line.

Now let’s try to think of frightening noises that zombies might make. Did his sheeted dead moan, shriek, wail, cry, or go “Woo-woo!” in the Roman streets? No, they did squeak and gibber, and they were far more horrible for having done so. If you asked everyone on earth to name two words to describe the noises made by ghosts, would anyone light on a pair more bizarre or more chilling than squeak and gibber? No, there is more here than mere antiquity.

Let’s turn to Macbeth’s famous curse about the pointlessness of human existence. Today we would say, Life sucks, or What’s it all about, anyway? or Can’t have nothin’, but Macbeth, whose dreams of dynasty were crumbling around him, cried,

. . . . . Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

The power of this cry from the heart rests on that immortal pair sound and fury. They are the clearest example of my thesis that Shakespeare had a genius for mixing verbal forms in arresting ways. In particular, notice that he defies the rules that we have all learned about effective writing. Strunk and White1are no doubt the best-known authorities on writing style, and they advise:

Rule 12: Use definite, specific, concrete language.

If those who have studied the art of writing are in accord on any one point, it is on this: the surest way to arouse and hold the attention of the reader is by being specific, definite, and concrete. The greatest writers are effective because they deal in particulars. Their words call up pictures. (pp. 15-16)

The word fury fits the case here, and, following Strunk and White, we might prolong the evocative effect by saying tempest and fury, or passion and fury, or raving and fury, or thunder and lightning, or storm and blast. But surely no one but him would have independently hit upon sound and fury, for although the latter term is vivid and evocative, the former term is emotionally neutral, dead, and evocative of nothing. It is hard to think of a less stirring word, less definite, specific, concrete. But it works, and we must assume that Shakespeare knew it would, but why does it work?

Let’s turn to another famous line. Horatio apprises Hamlet of the appearance of his father’s ghost

…in the dead waste and middle of the night

(or dead vast and middle of the night in the First Folio). Either way, dead waste and dead vast are evocative of that most desolate hour, the very witching time of night, when churchyards yawn, and hell itself breathes out contagion to this world. But middle? Could he have found a less evocative word to go with dead waste? Once again, we suspect a deliberate and careful choice of words. He was not merely yielding to the need to fill out a metrical foot, since strong and evocative words would have done as well. There appears to be a verbal device here that escaped Strunk and White. Does behavior analysis have anything to offer?

Not much, for the relevant behavior and corresponding variables are more than four centuries out of reach and would be difficult to measure at any time. But we are not entirely helpless; blogs are sufficiently unserious that rank speculation might be forgiven. Work pioneered by Kamin2 and developed by Rescorla & Wagner,3 and many others points to the role of blocking in the reinforcement principle. Stimuli are reinforcing to the extent that they are “surprising.” Donahoe4 has translated this finding into behavioral terms: a stimulus is reinforcing in proportion to the discrepancy between the behavior evoked by antecedent conditions and the behavior evoked by the putative reinforcer. We beam with joy when we are handed a fat check by the lottery commissioner, but our reaction is nothing compared to the leaping and cavorting that we engaged in when we discovered that the numbers on our ticket matched those of the jackpot. An on-line report that our salary has been deposited in our account is not as exciting as finding a $10 bill on the side of the road. Likewise, finding a second $10 bill a moment later is not quite as exciting as finding the first, for we have started from a baseline of delight. Our cat is more excited to hear the sound of a can of food being “popped” than she is by the food in the dish. Once she hears the former, the latter follows as a matter of course.

Is it possible that Shakespeare’s ear, as he scribbled away in his garret, detected that when a pair of words have the same valence, the effect of the second term is watered down by the effect of the first? Tempest and fury is not substantially more evocative than tempest alone, and fury reduces to a redundancy. The neutral word sound lulls us into a brief lassitude from which fury abruptly arouses us. Middle comes as a surprise after dead waste and is noticed for that reason. That is, we attend to middle of the night as a separate point in a way that we would not attend to gulf or any other word that echoed vast or waste. On the other hand, squeak and gibber both work because both words are utterly surprising; no one would predict the second from the first, and they join in alarming us in a way that wail and moan would not.

I do not claim to know the answer to the puzzle, for the matter in question is subtle, intangible, and fleeting. But I regard it as axiomatic that whatever the answer, it will lie in principles of behavior, for both writing and listening are behavior. Shakespeare was a wizard, an alchemist, who could transform a few leaden syllables into golden phrases, but he was a behaving organism, constrained by the same principles that governed pedestrian Loretta, and the path to understanding his genius is through behavioral interpretation.

- Strunk W. & White, E. B. (1959). The elements of style. New York: Macmillan. ↩︎

- Kamin, L. J. (1969). Predictability, surprise, attention, and conditioning. In R. Church & B.Campbell (Eds.), Punishment and aversive behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. ↩︎

- Rescorla, R. A, & Wagner, A. R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning. In A. H. Black & W. F. Prokasy (Eds.), Classical Conditioning II, (pp. 64-99). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. ↩︎

- Donahoe, J. W., Crowley, M. A., Millard, W. J., & Stickney, K. A. (1982). A unified principle of reinforcement. In M. L.Commons, R. J. Herrnstein, & H. Rachlin (Eds.), Quantitative analyses of behavior (Vol. 2): Matching and maximizing accounts. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger. ↩︎

Fun post! It’s fascinating to dissect the behavior dynamics of composition. I’d love to see a post that is prescriptive rather than descriptive, i.e., that lays out general principles of composition so that everyone could write a bit more like Shakespeare.

P.S. I can’t resist a nonsequitur: Once converted to zombie status, is a person still subject to operant processes? There’s a fungus that invades an ant’s brain and is said to “command” it to climb tall trees (from which spores can burst forth from the ant’s head and spread in the wind). But really there’s no “command;” the fungus simply make achieving higher altitudes reinforcing. Perhaps analogously, caffeine and other stimulant drugs “command” us to interact more with others (really, the drugs makes socializing more reinforcing). So, can whatever zombies do be explained in terms of operant principles? Or does the zombie virus create a new set of behavior laws?