I’m going to tell you a hopeful story about the evolution of one branch of behavior analysis and how different branches fit together. The data that the story tries to explain might not mean what I think they do [see Postscript 1 for some disclaimers and caveats], but this at least a plausible account.

If you care about behavior analysis, I think you’ll like this story, because it follows a narrative trajectory that people tend to find reinforcing. This type of story can be called Re-Reversal of Fortune [see Postscript 2] and in general it goes like this: A sympathetic main character begins in good circumstances (Sunny start), is beset by calamity (Dark Days) and ultimately is restored to good fortune (Brighter Skies). There’s decent circumstantial evidence that people find this kind of story reinforcing [see Postscript 2]. FWIW, it’s that shift from peril to prosperity that seems to harness listener motivating operations, that is, to keep people interested.

Now on to the story. It’s got an unconventional protagonist, though one that, no matter what your role in behavior analysis, you should care about: the basic-science wing of behavior analysis (i.e., the experimental analysis of behavior, or EAB). EAB might not be your thing but it’s the origin of many of our data-driven insights into how the universe of behavior operates.

EAB’s Re-Reversal Story

Sunny start. Skinner set EAB into motion with 1939’s Behavior of Organisms. A couple of decades later Schedules of Reinforcement provided a tour-de-force documentation of rock-solid regularities of behavior that even non-behaviorists couldn’t help but be impressed by. A year after that EAB got its own journal (Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, or JEAB), and it found instant success:

A reader of [JEAB] during its first 15 years would have seen many reasons for optimism about the future of the experimental analysis of behavior (EAB). This type of research had found a home in many academic institutions, including some of the world’s leading universities. Extramural research funding was available from several sources. EAB’s influence was palpable and growing: the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (JEAB) subscriptions were on the rise, and the journal was one of the scientific publishing world’s early leaders in citation impact factor. In some quarters, EAB was seen as illuminating behavior principles that would set the foundation for addressing the world’s great problems. [Mace & Critchfield, 2010 (in-text citations removed)]

That’s how things continued for quite a while. Probably the simplest way to assess EAB’s health is through a variant of the interocular percussion test. If you can, get your hands on a set of paper issues of JEAB. I’ll be obvious that those from JEAB’s earlier decades tend to have a lot of heft (meaning a lot of pages and content). They tend to feature a lot of different authors, and cover a fairly wide range of topics, all of which paints a picture of a robust science.

Dark days. But nothing lasts forever. By roughly the early 2000s considerable angst had emerged about EAB. Grant support had been drying up for years, and due to rising costs animal labs were shutting down. In this sense, it seemed society didn’t value basic behavioral science. A number of observers suggested a likely reason: At best the relevance of EAB to society’s well being was not unclear, and at worst EAB actually lacked relevance. Research questions were aimed at theoretical issues that not even most behavior analysts understood, and the procedures used to answer them were labyrinthine, often requiring sophisticated mathematical expertise to follow along.

Taking all of this in, Al Poling rather famously joked that “EAB” stood for “esoteric analysis of behavior.” The enterprise seemed to be stuck in old routines. “Change is unceasing,” Al wrote, and, “those organisms that adapt to it survive and, if they are human, carry forward elements of their culture. If they do not, they perish.”

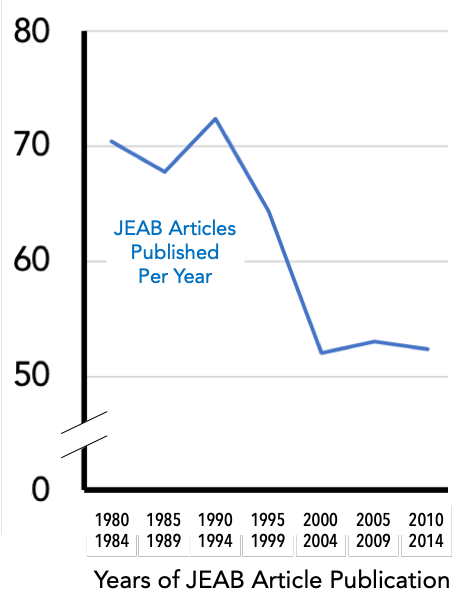

If you want a snapshot of how things were going for EAB, of whether “perishing” was plausible, look no further than JEAB, which was getting skinnier. The inset shows the number of articles published in JEAB in 5-year intervals. Note the steep decline beginning in the 1990s. By roughly the early 2000s it seemed that a handful of investigators accounted for an awful lot of JEAB’s remaining content, suggesting that the pool of EAB researchers might be shrinking, and JEAB was getting thinner.

Brighter skies. And now, as Re-Reversal stories demand at this juncture, let us rejoice! Because it seems that EAB, as measured through JEAB, is on the rebound.

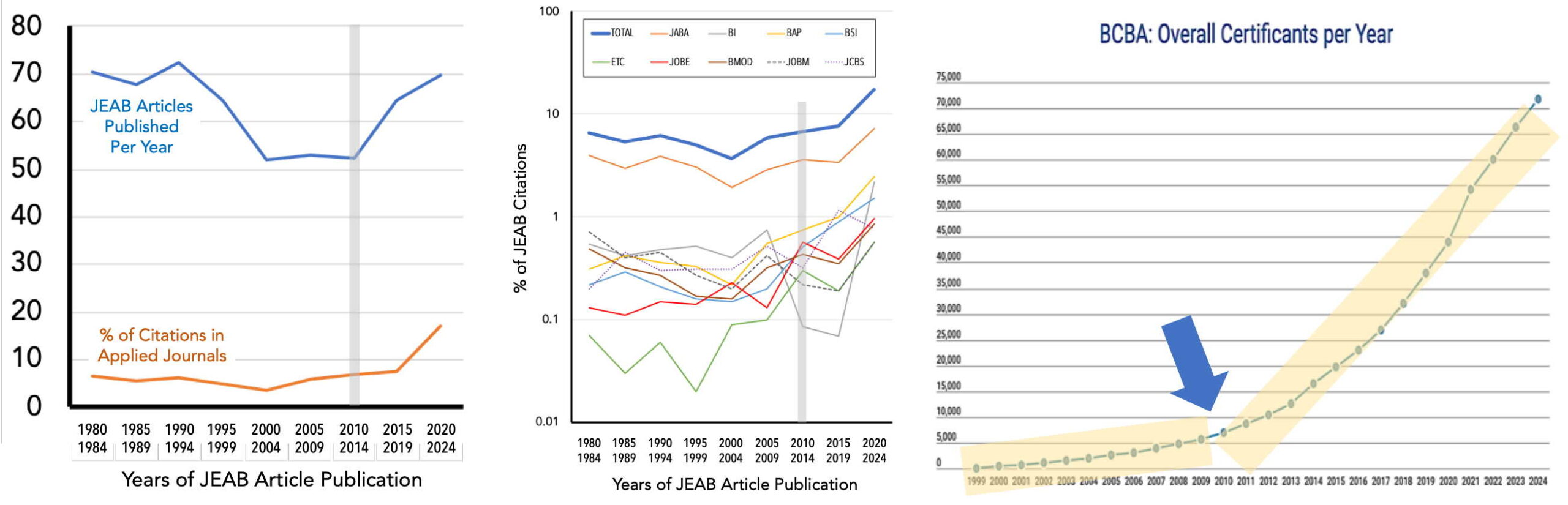

Below (left panel, blue function) shows that, since about 2010, JEAB has grown fatter, with the annual article count returning to early-1990s levels. Skim through recent issues and you see a variety of authors contributing a fair amount of topical variability. If those things measure a science’s vitality, then EAB seems to be doing all right again.

MIDDLE: JEAB citations from each of those 9 applied journals. Note the use of logarithmic scaling to show detail. Data from Web of Science.

RIGHT: The practitioner movement in ABA took off right around the same time as JEAB’s publication rate recovered [for the quantitative basis of this claim, see Postscript 2]. BCBA = Board Certified Behavior Analyst. Figure reproduced from the Behavior Analyst Certification Board website.

What Happened?

A lot of different factors might be responsible for this change [see Postscript 3], but allow me to suggest an explanation built around the orange function in the left panel above. Note how, accompanying the increase in publication rate, there’s an uptick in citations by applied journals (that is, the most recently-published JEAB articles have attracted the most citations from the nine applied journals I examined; the middle panel shows a breakdown by journal). What might account for that effect?

In 2010, JEAB appointed its first Associate Editor specifically to deal with translational submissions, and declared its interest in receiving translational submissions. “Translational” means different things to different people. but here’s a decent starter definition:

Now, there had been JEAB articles with a translational message prior to 2010, but that message tended to be advanced cautiously and/or shrouded in the turbid language of basic science. Since 2010, the journal has featured an increasing number of articles that are transparently, unabashedly translational, and that might explain its increasing citation attention from applied authors. It can’t, however, explain JEAB’s newly robust manuscript flow.

To do that requires a brief digression into the dynamics uniting our basic and applied wings. When certification and third-party pay mechanisms revolutionized ABA, including by driving massive demand for ABA graduate programs, there was a fair amount of gloom-and-doom talk in EAB circles. Basic science would become marginalized in graduate programs, and the supply of new EAB investigators would dwindle. According to the most pessimistic assessments, EAB might not be long for this world.

But if you check out the author bylines in recent JEAB translational articles, you see a lot of investigators whose bread and butter is applied research, or who cannot be comfortably categorized as basic or applied. It used to be rare for the same individuals to publish in JEAB and applied journals, but not any more. And I think a bit of lucky timing contributed to this outcome.

The right panel above shows cumulative new BCBA certificants, which unfolds in two phases [see Postscript 3 for the mathematical basis of this claim]: A phase of slow growth and then, starting around 2010, a phase of much faster growth. During that second phase a lot of new investigators at a lot of new graduate programs were devising research programs, and it appears that some of them embraced a translational perspective. This is not entirely surprising, since ABA had done more to define the translational agenda than EAB. As Bud Mace and I wrote in 2010:

ABA changed abruptly in the mid-1980s with the development of procedures for identifying the contingencies that maintain undesirable behavior. Known collectively as functional analysis methodologies, these procedures shifted the focus of ABA research to determining the factors that maintain undesirable behavior and using this information to promote replacement behaviors that serve the same function. When applied behavior analysts began to analyze behavior in this way, research in EAB became relevant to their work. It was not long before members of JABA’s editorial team began encouraging explicit connections with basic research. During part of the 1990s, JABA reprinted abstracts of selected JEAB articles, and around the same time Editor Nancy Neef established a regular series of explicitly translational essays that discussed the applied implications of JEAB basic research. Two JAB special issues featured the general theme of translation, and several other special sections and special issues have had a strongly translational flavor. [reference citations omitted]

So, to cut to the chase, beginning in the 1980s and 1990s ABA established a translational agenda, and by the 2000s and 2010s it was producing a lot of new investigators who were familiar with the agenda. In the 2010s, JEAB had the good fortune to open a conduit for translational research, from which it seems to have benefitted considerably. If I’ve gotten this story close to right, it takes the old worry that ABA growth would marginalize EAB and turns it on its ear.

This story also echoes Al Poling’s “adapt to survive” comment. EAB came into its own during a period of unprecedented societal focus on basic research driven by the Industrial Revolution and several wars, both hot and cold. During this era the concept of “pure basic” science crystalized as never before in history, in large measure because investigators embracing this concept could find employment and financial support. With “pure basic” science all the rage, EAB was a product of its times, sometimes rigidly so. As I wrote elsewhere:

When I began conducting basic research in the late 1980s, considerable peer pressure existed to adhere to the pure basic ideal. For instance, I recall colleagues who, after being driven to applied positions by a collapsing academic job market for basic scientists, were derided as having ‘‘sold out’’ or ‘‘gone soft.’’ There seemed to be limited interest among members of the EAB community in applied and translational issues.

Yet as Donald Stokes lays out in his fine little book Pasteur’s Quadrant, as the 20th Century wound down society was shifting its attention more toward mission-driven (applied) research. JEAB’s apparent decline (above), and EAB’s loss of grants and labs, are probable reflections of this new zeitgeist. But give credit where it is due: The EAB/JEAB community was wise enough to recognize changing times, and adapt to them. Ironically — at least from the vantage point of those who would see basic and applied science as separate or competing enterprises — the adaptation was to become more like ABA. If there is a moral to this story, it’s that behavior analysis functions best as one integrated science.

Postscript 1

Okay, sure, there could be a lot going on here other than what I suggest above. The function describing JEAB article counts could show random variation rather than cohesive trends. A lot of EAB-adjacent specialty areas other than ABA — behavioral economics, behavioral neuroscience, behavioral pharmacology, ethology, etc. — sometimes contribute to JEAB, and I haven’t attempted to account for their contributions. To properly substantiate my speculation would require a deep dive into who is authoring JEAB papers, on what topics; I didn’t provide that. And so on. As I said in my introduction, this post presents on plausible account — food for thought, but not a definitive analysis.

Postscript 2

What I call Re-Reversal of Fortune the novelist Kurt Vonnegut referred to as Man in a Hole but (I used a different label partly to avoid gender bias, partly because the present protagonist is not a [hu]man, and partly as a clunky pun since reversal designs have been such a prominent feature of EAB).

Vonnegut believed there were certain kinds of narrative arcs that recur in popular stories. Here he is explaining the proposition:

Vonnegut was, by the way, pretty much right. In 2016 a research team found a way to objectively evaluate Vonnegut’s thesis by tracking, not the fate of a protagonists per se, but rather estimates of “word emotion” (i.e., listener emotional responses, positive and negative) at different phases of a story. Applying this method to a large selection frequently-downloaded books on the Project Gutenberg web site, they found that just a handful of “story shapes” dominate the literature that people seek out, and Re-Reversal is one of them. If you loosely define a reinforcer as something an individual will expend time/effort/etc. seeking out and “consuming,” them we can reasonably call Re-Reversal and other popular narrative arcs reinforcers.

Postscript 3

Here’s how I defined the phases of growth in certification shown above. Using data from the BCBA I applied linear regression to different chunks of the growth function. A break point at 2010 yielded the best fits (i.e., the largest sum of r values). Note: I’m not claiming the phases are truly linear; other types of functions might produce better fits. But a biphasic linear perspective gets the point across.