Reprint of a post that originally appeared April 1, 2024

The iconic TV series The Simpsons began its epic run on this date in 1989.

Among the show’s nearly 800 episodes, only one has a special connection to behavior analysis.

As a scientist and social commentator, B.F. Skinner earned wide acclaim. During Beyond Freedom and Dignity’s 18-week run on the N.Y. Times Bestseller List, he even made the cover of Time magazine. Unsurprisingly, cultural references to Skinner and operant learning abound, including:

- A famous New Yorker cartoon about operant conditioning that pretty much every behavior analyst (and Introductory Psychology student) will recognize.

- A Superman graphic novel showing a copy of Walden Two on Clark Kent’s nightstand.

- A Big Bang Theory episode in which Sheldon attempts to apply positive reinforcement.

- The Pixar film Ratatouie, featuring a preternaturally intelligent rat, in which evil chef Skinner is B.F.’s namesake.

And so on. For better or worse, if you pay attention, B.F. Skinner is everywhere. And yet few people are aware of Skinner’s presence on one of the biggest stages of contemporary culture.

Yep. I’m talking about the TV series The Simpsons, in an episode whose incoherent narrative earned it the designation as one of the worst installments ever in the show’s storied run (though maybe not the absolute worst). “The Principal and the Pauper” (Season 4 Episode 16) was so unpopular that, as Morrow (2022) notes, later installments erased most of its plot points from Simpsons‘ canon, and it is no longer included in commercially-available collections of Simpsons episodes. As a result, most people have never seen it.

The episode opens with a montage of the Simpson family on vacation in Boston, including a moment of foreshadowing in which Bart spray-paints B.F. Skinner graffiti on a wall at Harvard University.

During this setup there’s also an Easter egg in which the Boston Convention Center appears briefly in the background, hung with a banner stating “Welcome Association for Behavioral Psychology.” If you look carefully you can see pigeons perched everywhere, pecking at… just about everything (the banner, a gargoyle, a person’s head, etc.).

Typical of a Simpsons episode, the plot is loose and full of non sequiturs (like “America Balls,” a snack consisting of a dollop of dog food with a little American flag stuck into it). But here’s its critical narrative thrust, as explained by Morrow (2022):

First aired on September 28th, 1997, with a script by Ken Keeler and directed by Steve Moore, “The Principal and the Pauper” begins with a celebration of Seymour Skinner’s 20 years as principal of Springfield Elementary, an event unexpectedly attended by a man claiming to be the real Seymour Skinner. The newcomer — played with dry realism by Martin Sheen — reveals the imposter to be Freddy, the son of Behavioral Psychologist B.F. Skinner. In a Simpsonian twist of fate, Freddy is Seymour’s doppelganger, and long ago replaced him in order to test his father’s theories about human behavior on the children of Springfield Elementary.

From an audience perspective, this development is deeply meta given that:

- The Principal Skinner character was actually named after B.F. Skinner.

- The real B.F. Skinner was often falsely said to have neglected or abused his children.

- (Imposter) Principal Skinner, in keeping with public perceptions of “behavior modification,” is a strict disciplinarian.

- Simpsons’ writer Ken Keeler was born in Cambridge, MA, only a stone’s throw from Skinner’s home, and graduated with two degrees from Harvard.

According to a flashback sequence, Freddy isn’t widely known because his father forgot to release him from his air crib until he was 29. Once freed, Freddy, who is hungry for his father’s approval and knows about B.F.’s World War II efforts to create pigeon-guided missiles, volunteers for military duty and ends up serving alongside Seymour Skinner in Vietnam. When Seymour goes missing and is incorrectly presumed dead, Freddy seizes his opportunity and Seymour’s identity.

Among many plot gaps, the episode doesn’t explain why it took Seymour 20 years to return to Springfield or why the town feels comfortable immediately installing this relative stranger as Principal.

Still, Freddy is cast aside and falls on hard times. He takes a series of menial positions, including as a barker for a strip club called “Topless Nudes,” a job for which he’s hilariously unsuited due to the rigidly monotone delivery of voice actor Harry Shearer (for laughs, compare Shearer’s performance to Skinner’s own voice, starting at about 1:30 of this video clip; take it a step further and imagine the uber-serious B.F. of the video clip hawking a strip club).

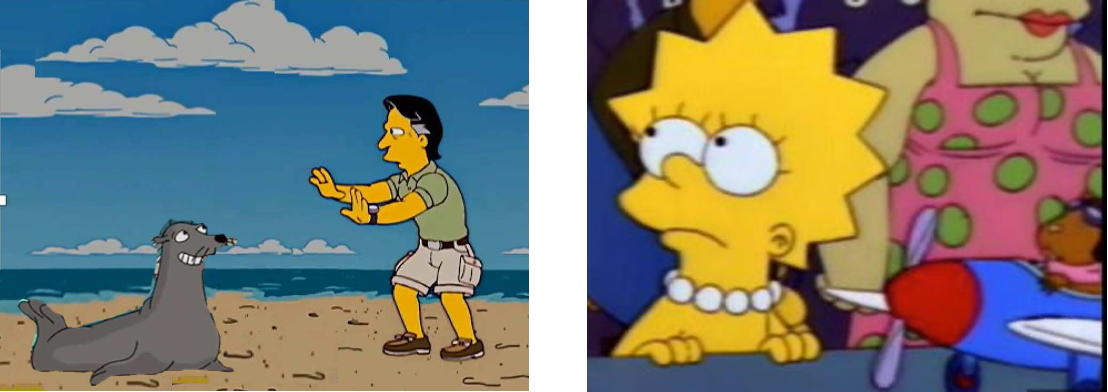

Freddy is also shown as an inept animal trainer at the Springfield Zoo, attempting to clicker-train a seal which, after disdainfully staring him down for a long moment, swallows the clicker.

By the end of the episode, Freddy has become such a nuisance that the residents of Springfield tie him to a chair on a flatbed rail car heading out of town, and he never again appears on the show.

The episode closes with Lisa presenting at the school science fair, where she is aghast to find that (in the writer’s possible creative swipe at B.F.’s guided missile work, and perhaps also a later project), the Principal has awarded first prize to a hamster sitting in a model airplane, wearing a miniature aviator outfit. Says Seymour, by way of unembarrassed explanation: “Lisa, every good scientist is half B.F. Skinner and half P.T. Barnum.”

Nobody is exactly sure what those words mean, but they are words to live by.