Guest Blog Authored By: Tiffany Kodak, Brittany Brown, and Brianna Duszynski

Marquette University

Dr. Tiffany Kodak is a Professor in the Behavior Analysis program at Marquette University. She is a licensed psychologist, licensed behavior analyst, and BCBA-D. Dr. Kodak received her Ph.D. in School Psychology from Louisiana State University. She is the Editor in Chief for The Analysis of Verbal Behavior on serves on several other editorial boards. Her research interests include increasing the efficacy and efficiency of skill acquisition, treatment integrity, assessment-based instruction, verbal behavior, and conditional discrimination.

Brittany Brown is a second-year doctoral student in the Behavior Analysis program at Marquette University. She received her master’s degree in applied behavior analysis from Marquette University and is a licensed behavior analyst. Brittany’s research interests include error correction and its effects on skill acquisition, verbal behavior, and conditional discrimination training. She enjoys reading Stephen King novels, playing with her dogs, and hanging out with family and friends.

Brianna Duszynski is a second-year doctoral student in the Behavior Analysis program at Marquette University and a licensed behavior analyst. Brianna received her master’s degree in applied behavior analysis from Marquette University. Her areas of research include varying economies and the effects on skill acquisition, error correction, and verbal behavior. Outside of graduate school, her interests include spending time with family and friends, hiking, attending music festivals, and cheering on Wisconsin sports teams.

How Verbal Stimuli Shape Everyday Interactions

People encounter verbal stimuli throughout everyday interactions with their environment. For example, when people read an email, watch a short video, talk to a friend, listen to music, or attend a class lecture, they engage in verbal behavior under the control of verbal stimuli in differing configurations. One type of verbal behavior under the control of verbal stimuli is an intraverbal. B.F. Skinner (1957) described the intraverbal as behavior under the control of a verbal stimulus that lacks point-to-point correspondence between the verbal stimulus and response. For example, the verbal stimuli, “What should we eat for breakfast?” might produce the response, “Let’s have blueberry pancakes,” which is not identical to the question (i.e., lacks point-to-point correspondence).

Intraverbals are an important type of verbal behavior because they form the foundation for conversations. When talking with a friend about something exciting that happened that day or discussing where to go on vacation with a partner, people engage in intraverbals. An intraverbal repertoire requires some prerequisite skills. Although learning intraverbals and their prerequisite skills may require specialized intervention for some people (e.g., neurodiverse children and adolescents), they are important skills to acquire because having conversations helps people build and maintain a number of other social skills, including creating lasting friendships, developing romantic relationships, and obtaining employment (Sundburg & Sundburg, 2011).

How To Teach Intraverbals?

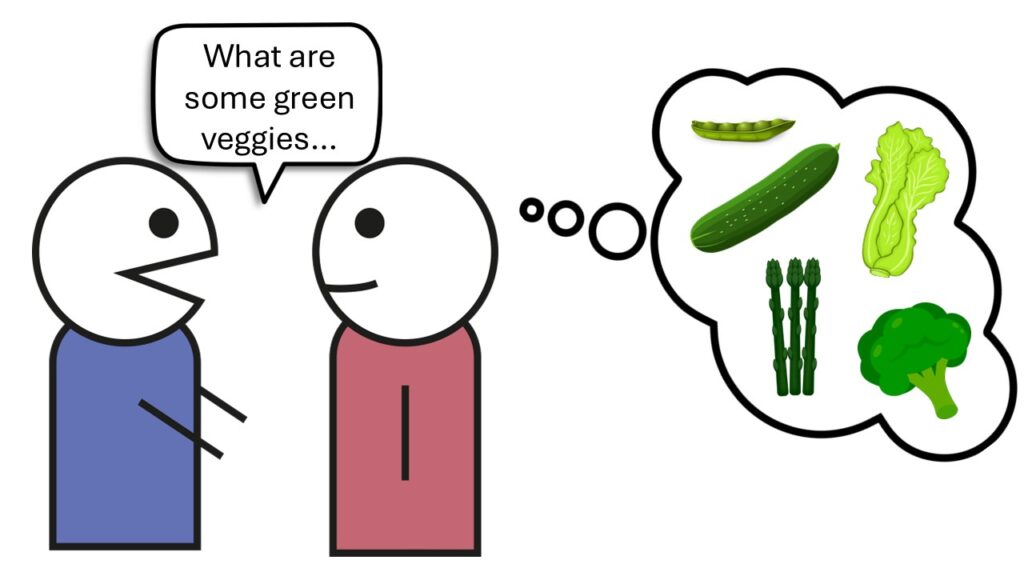

When teaching intraverbals, it is important to consider the complexity and configurations of verbal stimuli. We will focus on a discussion of simple and conditional discriminations. A verbal simple discrimination involves a response to one component of a verbal stimulus. For example, the verbal stimulus drink in “you drink…” might evoke the response “water.” Said another way, a learner only needs to pay attention to one part of a question (e.g., “drink”) to answer correctly and engage in a verbal simple discrimination. Simple discriminations establish a foundation for more advanced intraverbal behavior and are often acquired in early development (e.g., neurotypical children aged 1.5-3 years old; Sundburg & Sundburg, 2011). Many verbal simple discriminations are taught before teaching verbal conditional discrimination (Sundberg, 2016). A verbal conditional discrimination involves a response to two or more components of a verbal stimulus in which one of the verbal stimuli alters the evocative effect of another verbal stimulus (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011). In this case, a learner needs to pay attention to several parts of a question to answer correctly. Let’s say two friends are at a restaurant talking about potential side dishes to order and share for dinner. One friend asks, “What types of green vegetables do you eat?” The verbal stimuli green and vegetables alter the evocative effect of the verbal stimulus you eat. An appropriate response to this friend’s question would involve only green vegetables that they eat such as “cucumber” or “peas,” rather than other green vegetables that they don’t eat (e.g., they don’t like broccoli, lettuce, and asparagus). Also, the answer to this question should not include vegetables that are different colors (e.g., carrots, radish) or other foods that are green but are not vegetables (e.g., mamoncillos, pesto pasta, sweetsop, pistachios).

Images created by the authors using Pixabay.

Next, we will describe a sequence of steps to assess and teach intraverbal behavior and related skills.

STEP 1: Assessment of Intraverbals. One way to assess a learner’s intraverbal repertoire is to use an 80-item intraverbal assessment developed by Mark Sundberg (2016). Questions are divided into 8 groups of 10 questions, and the complexity of the intraverbals increases across groups. For example, groups 1 and 2 assess simple discriminations such as fill-in-the-blank questions or songs (e.g., “You brush your…” and “Twinkle, twinkle, little ___”). Subsequent groups measure intraverbals under the control of more than one verbal stimulus. For example, in group 5, “What shape are wheels?” and “What color are wheels?” require verbal conditional discrimination because the evocative effect of wheels is altered by color or shape in these questions. The number of verbal stimuli that control a response increases in the last groups, such as “What number is between 6 and 8?” in group 7 and “Why do people wear glasses?” in group 8.

The intraverbal assessment allows the clinician to measure responding to intraverbals of increasing complexity, identify the type(s) of verbal stimuli that control responding, and guide future programming. Once the intraverbal assessment is completed, the clinician should interpret the data in several ways.

- First, look at changes in correct responses across groups. For example, suppose a learner has many correct responses in early groups that measure simple discrimination but makes many errors in groups that require conditional discrimination. In that case, this indicates a skill deficit in verbal conditional discrimination. The clinician should note this deficit and prepare a plan to address it.

- Second, look at the potential sources of control for responding. The source of control refers to the specific verbal stimulus/stimuli that evoke a response. Identifying the source(s) of control will clarify why a learner responds (or fails to respond) to specific verbal stimuli. For example, if the learner typically provides a single response (e.g., red or dog) to the questions, “What are some colors?” and “What are some animals?” respectively, this pattern of responding indicates a deficit in a specific type of control to the verbal stimulus some (i.e., divergent control; refer to Sundberg, 2016).

- Finally, the results of this assessment can determine a starting point for the learner’s instruction. Intraverbals are typically taught in a progression, starting with simple and moving to more complex discriminations (Sundburg & Sundburg, 2011). By determining a starting point and teaching intraverbals (and other related behavior) in a hierarchical sequence, the foundational skills necessary to develop a complex verbal repertoire are established.

STEP 2: Identify Targets to Teach. The results of the intraverbal assessment are used to identify targets to include in intraverbal instruction. Note that the assessment evaluates changes in intraverbal behavior following intervention. Thus, answers to the specific questions included in the intraverbal assessment should not be taught during intervention.

Example: Learner who only has some correct responses in group 1 of the intraverbal assessment

If a learner responds correctly to fill-in-the-blank songs in group 1 and does not respond correctly to other fill-in-the-blank intraverbals in groups 1 and 2, then working on early fill-in-the-blank intraverbals (e.g., sounds made by animals and objects) and intraverbal associations (e.g., toothbrush and toothpaste) could be the target of instruction.

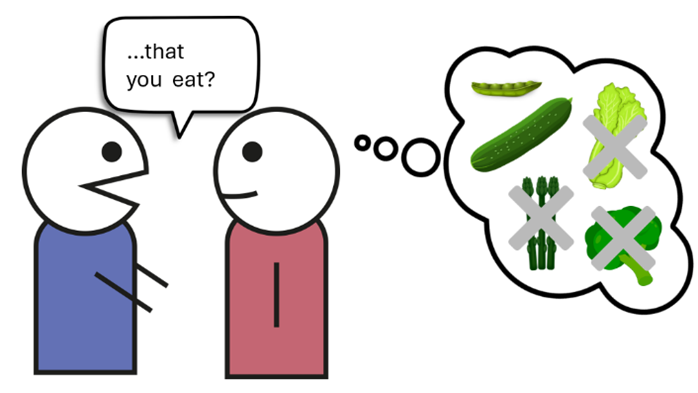

Selecting targets to include in instruction is an important step in programming. When targets look or sound similar, we refer to those stimuli as having low stimulus disparity (Halbur et al., 2021a). For example, cat and bat rhyme and would be considered low-disparity stimuli. Some learners may have difficulty acquiring targeted skills if stimulus disparity is low (Halbur et al., 2021b). Therefore, targets for early intraverbal instruction should sound different. The table below gives an example of two sets of high-disparity targets because the stimuli within the teaching set are comprised of different sounds. ‘Cat’ and ‘cow’ both start with the same sound (“c”), and the response also starts with the same sound (“m”). Therefore, these targets were placed in different sets to avoid grouping similar-sounding stimuli in the same set.

STEP 3: Prerequisite Skills. Before teaching the simple discrimination sets of targets listed in Step 2, it is beneficial to teach other verbal behaviors related to these intraverbals (DeSouza et al., 2019). For example, if targeting animal sounds, the clinician could ensure the learner has acquired related skills (or teach them), such as labeling pictures of animals, pointing at the animals in an array when their sounds are provided, and making the animal sound when shown the animal. Clinicans should teach prerequisite skills if the learner does not readily demonstrate them (e.g., during probes), and the teaching sequence could be based on previous research (DeSouza et al., 2019).

DeSouza et al., (2019) systematically introduced verbal operants when teaching complex intraverbals. They started by teaching multiple tacts (names of targets, their category, their biome) related to the targeted intraverbals (e.g., zebra, mammal, savannah), followed by listener responses (e.g., “point to the zebra”), intraverbal categorization (e.g., “tell me some mammals”), and finally listener compound discriminations (e.g., “point to the mammal from the savannah”). Their results showed that more complex intraverbals (e.g., “a mammal from the savannah is…”) emerged without direct teaching for all participants after acquiring the prerequisite skills.

STEP 4: Teaching Verbal Conditional Discrimination. Once the learner has a foundation of verbal simple discrimination and other related skills, the clinician can begin teaching early verbal conditional discrimination (Axe, 2008). In the intraverbal assessment (Sundberg, 2016), group 5 assesses some responses under the control of two or more components of the question. For example, “What shape are wheels?” and “What color are wheels?” include one component (shape vs. color) that alters the evocative effect of a second component (wheels). Relatedly, the question, “Where do you find wheels?” includes a wh question (where) that alters the evocative effect of wheels.

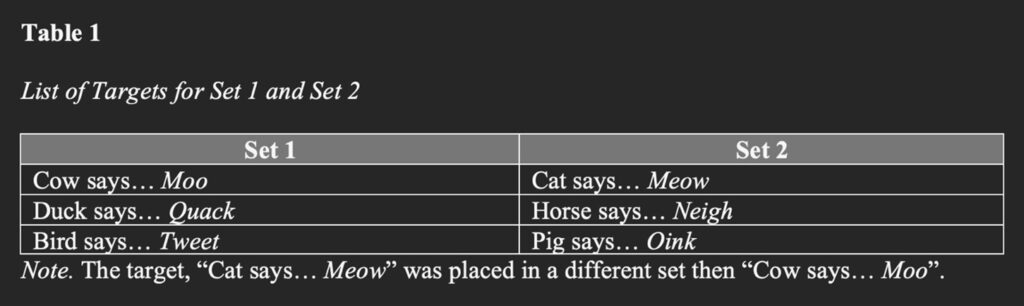

One option to teach verbal conditional discrimination is to target verbal stimuli that vary by feature and category. In the example data sheet below, the target verbal stimuli vary by either color or category and the learner must attend to and differentially respond based on both of those verbal stimuli. As indicated previously, it is important that the learner has relevant prerequisite skills including labeling pictures of green and red fruits and vegetables by the object, color, and category and responding as a listener to green and red vegetables and fruits based on color and category (e.g., touching the green vegetable in an array with a different color vegetable and another green object).

Image created by the authors.

Addressing Common Errors

Some challenges may occur when teaching verbal conditional discrimination. The types of errors made during instruction provide information about potential barrier(s) to learning. For instance, a common barrier to learning is restricted stimulus control (Kisamore et al., 2016), which occurs when a learner does not attend to all relevant components of a verbal stimulus. For example, the learner may respond similarly (e.g., broccoli) when asked about a green versus a red vegetable. An intervention modification that could resolve restricted stimulus control includes a differential observing response (DOR; e.g., Kisamore et al., 2016). In simple terms, this means requiring the learner to perform some related or unrelated behavior prior to the presentation of each target stimulus. For example, participants can be asked to repeat a color name after the clinician says the color (e.g., green), then repeat the category after the clinician says the category (e.g., vegetable).This can help to ensure that the learner attends to each component of the verbal stimulus that should control a response.

A within-stimulus prompt is another intervention modification that could resolve restricted stimulus control. Halbur et al. (2023) used two within-stimulus prompts during intraverbal instruction to increase attending to the components of verbal stimuli. The clinician either elongated (e.g., elongating the color; “grreeeeeen vegetable”) or emphasized one verbal stimulus (e.g., saying the color louder; “GREEN vegetable”). Some fading of the within-stimulus prompt (e.g., gradually decreasing the emphasis so eventually the voice volume is the same for all verbal stimuli) may be needed to remove the emphasis or elongation and still maintain correct intraverbal behavior.

Both DORs and within-stimulus prompts can address restricted stimulus control, and the clinician can determine which method might be most effective for their learner and most feasible for the clinician to conduct during appointments. Furthermore, if the clinician decides to use within-stimulus prompts, we recommend either emphasizing or elongating the verbal stimulus that the learner is not responding to during instruction. For example, if the learner responds to the color only (not the category), then the category verbal stimulus would be manipulated (e.g., say vegetable or fruit louder or in an elongated way).

In summary, we present a sequence of steps clinicians can take to assess and teach an important type of verbal behavior to a learner needing specialized instruction. Clinicians may find this recommended sequence of steps helpful when designing instruction, and researchers may identify ways to expand upon these recommendations to develop more effective and efficient practices. Both clinicians and researchers can continue to refine and innovate teaching strategies, ultimately enhancing outcomes for learners and contributing to the broader understanding of verbal behavior.

References

Axe, J. B. (2008). Conditional discrimination in the intraverbal relation: a review and recommendations for future research. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 24(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393064

DeSouza, A. A., Fisher, W. W., & Rodriguez, N. M. (2019). Facilitating the emergence of convergent intraverbals in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.520

Halbur, M.E., Caldwell, R.K. & Kodak, T. (2021a). Stimulus control research and practice: Considerations of stimulus disparity and salience for discrimination training. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14, 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00509-9

Halbur, M., Kodak, T., Williams, X., Reidy, J. and Halbur, C. (2021b). Comparison of sounds and words as sample stimuli for discrimination training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54, 1126-1138. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.830

Halbur, M., Kodak, T., Reidy, J. & Bergmann, S. C. (2023). Comparing manipulations to enhance stimulus salience during intraverbal training. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-023-00190-3

Kisamore, A. N., Karsten, A. M., & Mann, C. C. (2016). Teaching multiply controlled intraverbals to children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(4), 826–847. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.344

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Sundberg, M. L., & Sundberg, C. A. (2011). Intraverbal behavior and verbal conditional discriminations in typically developing children and children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393090

Sundberg, M. L. (2016). Verbal stimulus control and the intraverbal relation. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 32(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-016-0065-3