Much of the present post is based on the following two sources. Both are recommended reading.

- Pettit, M. (2010). The problem of raccoon intelligence in behaviourist America. The British Journal for the History of Science, 43(3), 391-421.

- Boakes, R. (1984). From Darwin to behaviourism: Psychology and the minds of animals. CUP Archive.

Recap of Part 1: Enter the Raccoon

Readers of this blog know that, ever since B.F. Skinner’s pioneering research of the 1930s, experimental behavior analysis has relied heavily on studies of rats and pigeons. In the decades before Skinner, however, just as Psychology was finding its scientific footing, there was considerable interest in studying and comparing the behavioral repertoires of a variety of species, in search of an evolutionary continuum of “intelligence.” Lawrence Cole and H.B. Davis thought that raccoons were particularly human-like, perhaps challenging even the apes in this regard, and would therefore make an ideal laboratory model of behavior. Their pioneering experiments with raccoons produced intriguing data and fueled their contention that experimental Psychology would be inherently incomplete as long as it remained “species blind.”

The work of Cole and Davis was praised by many leading lights of the day, including Robert Yerkes and Herbert Spencer, and J.B. Watson even said that the “results of Cole’s study of the intelligence of the raccoon probably constitute the most important contribution to comparative psychology that has yet been made by a single investigator.” Despite such hoopla, check the literature of just a few decades after Cole and Davis, and you’ll find scarce mention of their work — and this says a lot about the scientific and cultural niche that behavior analysis would come to occupy.

Exit the Raccoon

It’s curious. Despite having had quite a moment in the early-1900s spotlight, neither Cole nor Davis, nor raccoons in any fashion for that matter, are mentioned in most contemporary behavior principles textbooks….

- Examples: Powers and Osborne’s (1976) Fundamentals of Behavior, Fantino and Logan’s (1979) The Experimental Analysis of Behavior, Mazur’s (2006) Learning and Behavior, and Madden et al.’s (2021) Introduction to Behavior Analysis.

Ditto for volumes on comparative psychology…

- Examples: Denny and Ratner’s (1970) Comparative Psychology, Roitblat et al.’s (1984) Animal Cognition, Ristau’s (1991) Cognitive Ethology, Pearce’s (2008) Animal Learning & Cognition, and Zentall and Wasserman’s (2012) Oxford Handbook of Comparative Cognition

Which begs the question: With raccoons so easy to come by in the wild and so intriguingly “human-like,” and with Cole and Davis providing such high-profile early investigations, how did studies of raccoon learning NOT become a major part of experimental psychology?

A whole host of reasons, actually, but particularly the following.

A CHANGING ZEITGEIST

As behavioristic ideas began to take shape in the first few years of the 20th Century, a groundswell of objection arose to breathlessly anecdotal, and hopelessly subjective, reports of animal “intelligence” (like those in Romanes’ Animal Intelligence that had originally fueled the interest of people like Cole and Davis). It did not help that 1907 was also the year when, to considerable fanfare, Oscar Pfungst debunked the myth of Clever Hans, the horse that had widely been thought capable of counting. After that, scholars began to cast increasing skepticism toward claims of special animal intelligence that might represent unwitting misinterpretation or even fakery. And, importantly, although Cole and Davis had conducted useful experiments, they became the focus of blistering criticism for their tendency (illustrated in Part 1 of this post) to assert more about raccoons than perhaps the available data justified. To some degree, their studies were the babies that got tossed out with this era’s bathwater.

TRASH-PANDA-MONIUM

Once unhitched from the preconception that raccoons are intellectually special, researchers began to gravitate to other species, more for convenience than for phylogeny.

Image by pasi.

For example, the year 1906 marked the introduction of the first bred-for-research rat strain, the Wistar, and rats offer many practical advantages, including that they don’t require much space, don’t eat a lot, and are easily tamed. Moreover, because rats were valued by medical researchers, commercial rat breeders could operate at high volume and deliver them cheaply.

Raccoons, by contrast, are an incredible pain in the ass in nearly every respect.

They are much bigger than rats and eat voraciously (and they poop about as much as a medium-sized dog, though it reportedly smells much worse). In the early 20th Century there were no commercial raccoon breeders, so you had to capture subjects and/or maintain a breeding colony. If you caught wild raccoons there was a risk of rabies and other diseases, and even without that worry, fully taming a wild mature raccoon is regarded as all but impossible. If you tried to breed raccoons, you encountered a number of species-specific challenges. Even if you had ready access to raccoons that could be raised from cubs, they would be difficult lab residents. Here’s a description of raccoons-as-pets from a web site that is in favor of the idea.

Raccoons live up to all the nicknames they have acquired over the years. They are very curious. They do have a tendency to want things on their terms. Their attitude is, if I can get away with it I will. They love to explore every nook and corner they find…They can be very destructive at times. It’s not that they are malicious; they are just very curious. They love water, bath, toilet, kitchen sink, you get the picture…. Raccoons are notorious for climbing. So yes they do climb furniture and anything else that is climbable…. They… always have those busy little fingers investigating holes and crevices.

The above [see also Postscript 3, in Part 1 of this post, plus a recent news story about a raccoon crashing through the ceiling of an airline ticket counter] prepares you for the experiences of early-1900s researchers in working with the little brats:

[Walter] Hunter detailed the major practical difficulties in maintaining such a colony especially during the spring when ‘”wanderlust” strikes them’. During such periods the creatures would gnaw the wood and tear at the wire of their cages trying to escape, biting him when he tried to contain them…. Davis documented a break-out of six of his subjects with a number of them hiding in the building’s ventilation system…. Cole bemoaned the many days of work during which the ‘coons were stupid’ due to their propensity to slow down during the colder, winter months, and that they were a ‘nuisance to care for.’ (Pettit, 2010, p. 416).

Watson had used rats in his 1903 dissertation. Skinner also favored rats (which were the main focus of his 1939 book The Behavior of Organisms) and never gave much systematic attention to possible species differences in learning mechanisms, emphasizing instead that his was a general theoretical framework. This perspective provided little incentive for followers to deviate from Skinner’s reliance on rats and, later, pigeons, especially since Skinner had done such a good job of working out reliable methods for studying operant learning in those species.

AND SO WHAT?

In the end, there are no heroes or villains in this story, only a host of factors that combined to nudge one branch of experimental psychology in particular directions.

The story of raccoon psychology thus traces a rollercoaster trajectory. “Raccoon” doesn’t appear in the index of Romanes’ 1882’s Animal Intelligence, and about half a century later, it’s also absent from the indices of two manifestos of emerging behaviorism, Skinner’s 1939 Behavior of Organisms and Tolman’s 1932 Purposive Behavior in Animals and Men (the latter being especially noteworthy given Tolman’s sympathy with the Cole-Davis assumption that animals have human-like psychological capabilities). In between, there was a brief spark of interest in the learning capabilities of this creature [see Postscript 8], though of course a systematic “raccoon psychology” never materialized.

Should we care about that? After all, things come and go in the research world, and few mind that introspectionism and the Stanford Prison Experiment and autoshaping have faded into obscurity.

You’ve probably never laid awake at night, tortured by failing to find a lot of published raccoon experiments. But raccoons per se are not the issue. It’s the forces that marginalized raccoon research that matter, because they eventually contributed to two contemporary problems — one of which particularly troubles behavior analysts.

Problem #1: Comparative Psychology’s Failure to Launch

Let’s start with the easier of two answers to this question. Even if raccoons per se aren’t important, the extent to which behavioral processes operate identically across species is. For instance, whereas many basic operant phenomena like positive reinforcement clearly cut across a hell of a lot of species, one of the major curiosities in contemporary behavior analysis is whether any species other than homo sapiens demonstrates derived stimulus relations (perhaps some have, but if so, it’s not a lot of species, and the effect is really tricky to produce).

According to Pettit (2010), “In 1907 the studies of Cole and Davis marked the forefront of a truly comparative psychology.” But those studies also revealed some significant pitfalls that comparative psychology would need to overcome in order to reliably map psychological similarities and differences among species. It might seem trivial to point out that difficulties arise when figuring out how to incorporate a new species into lab operations, including both its daily care and the means of testing its capabilities. Regarding the former, we’ve seen the headaches that come with maintaining a raccoon colony. Regarding the latter, the only way to compare species capabilities is to standardize the means of testing them, while somehow also adapting methods to individual species (Not easy! For example, see here for the travails of Ogden Lindsley in developing the first operanda for human operant experiments). And by the way, every time you modify how your lab operation it costs you time and productivity. It’s telling that even Yerkes, in most respects a Cole cheerleader, himself only worked with a handful of species.

For a very long time, most “comparative” psychology actually involved few direct interspecies comparisons. Rather, different labs focused on different individual species — still, quite often, rats and pigeons — often using methods that were tailored to a single species. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, fast forward to 1960, and you see Bitterman advocating for the brand of comparative psychology that might have emerged at the turn of the century, at least the part about understanding the psychological relationships among different species through direct comparison. Fast forward another 30 years and you see Dewsberry making some of the same arguments.

Unless the intent is expressly to specialize in a single species (e.g., “rat psychology“), a science of behavior ought to encompass behavior in every species that exhibits it. But circumstances of the early 20th Century conspired to greatly limit the range of species that animal learning experiments examined. One wonders how comparative psychology might have evolved differently had early work like that of Cole and Davis found a more receptive audience. As I’ll show next, this question isn’t entirely unrelated to the concerns of the present audience.

Problem #2: Seeds of Discontent with Behaviorism

Now let’s move on to the thornier issue where behavior analysis is concerned. Yes, Cole and Davis were conceptually sloppy, taking explanatory cues from traditions to which early behaviorists strenuously objected, but they conducted experiments that were possibly as rigorous as others of their era, reminding us of the old saw that data are data, regardless of how an author might talk about them. When researchers lost interest in the raccoon, however, raccoon data were largely forgotten.

Here’s an example of what was left behind. Hunter (1914) conducted a comparative experiment with raccoons, dogs, children, and rats. On each trial, one of three lights would be illuminated, each correlated with a different response that could produce food. The designated light was briefly turned on, then off during a delay until it was possible to make a response. Clear species differences were found. For example, rat performance fell to chance levels with a delay of more a second, whereas raccoons could tolerate delays up to 25 seconds, and dogs up to 5 minutes. However, for rats and dogs, delay tolerance only held if, during the delay, they were able to stay physically oriented toward the correct response option during the delay. For raccoons, physically orienting proved unnecessary.

What all of this means is hard to say, but it’s pretty interesting, and with the stalling out of turn-of-the-century comparative psychology was lost (or at least deferred) an opportunity to dive in and find out more. Among those least interested in finding out were early behaviorists. They had other priorities. Although, in his book on comparative psychology, Watson allowed that he could not explain Hunter’s results, he made no effort to try unpack them experimentally. Skinner tended to view species differences as noise with the potential to drown out more-important continuities of principle. For example, in 1956 he presented a now-famous figure showing three nearly identical cumulative records, juxtaposed with the question, “Pigeon, rat, monkey, which is which?” His answer:

It doesn’t matter. Of course, these three species have behavioral repertoires which are as different as their anatomies. But once you have allowed for differences in the ways in which they make contact with the environment, and in the ways in which they act upon the environment, what remains of their behavior shows astonishingly similar properties. Mice, cats, dogs, and human children could have added other curves to this figure. And when organisms which differ as widely as this nevertheless show similar properties of behavior, differences between the same species may be viewed more hopefully. Difficult problems of idiosyncrasy or individuality will always arise as products of biological and cultural processes, but is it the very business of the experimental analysis of behavior to devise techniques which reduce their effects except when they are explicitly under investigation.

In short, Skinner and his intellectual descendants largely left comparative questions to others, an approach that unfortunately, to some, signaled that that behavioral psychology had fatal shortcomings.

RACCOON’S REVENGE

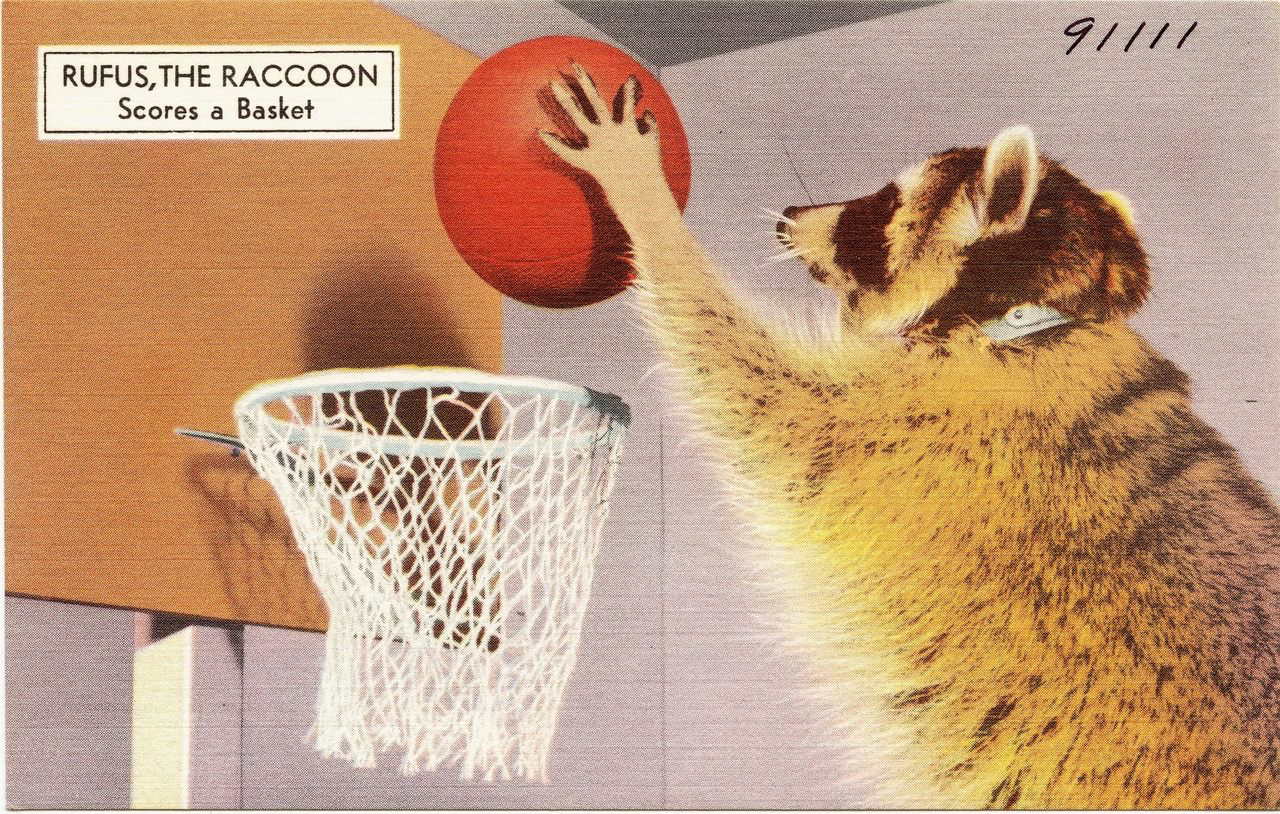

Public domain image.

It’s ironic that when the raccoon finally did claw its way onto the scene in behavioral psychology, it was in the Breland and Breland (1961) article, “The Misbehavior of Organisms,” which a lot of people took as dismantling Skinner’s general-principles approach to learning (for some context on the Brelands’ work, see Postscript 5).

The paper led off with a sentiment seemingly lifted directly from Cole and Davis: “Perhaps the white rat cannot reveal everything there is to know about behavior.” It proceeded to relate several stories about attempts to use operant techniques to teach a variety of behaviors to a variety of (non-rat) animals… attempts that in various ways went off the rails. One of the more famous cases is that of the “Miserly Raccoon,” who was taught, through a rigorous shaping program, to pick up a coin and deposit it in a piggy bank. The problem?

He seemed to have a great deal of trouble letting go of the coin. He would rub it up against the inside of the container, pull it back out, and clutch it firmly for several seconds. However, he would finally turn it loose and receive his food reinforcement. [When a second coin was introduced], not only could he not let go of the coins, but he spent seconds, even minutes, rubbing them together (in a most miserly fashion), and dipping them into the container. He carried on this behavior to such an extent that the practical application we had in mind—a display featuring a raccoon putting money in a piggy bank—simply was not feasible. The rubbing behavior became worse and worse as time went on, in spite of nonreinforcement.

About this and other cases the Brelands wrote:

These egregious failures came as a rather considerable shock to us, for there was nothing in our background in behaviorism to prepare us for such gross inabilities to predict and control the behavior of animals with which we had been working for

years. The examples listed we feel represent a clear and utter failure of conditioning theory. They are far from what one would normally expect on the basis of the theory alone.

What actually happened with the Miserly Raccoon and his non-rat compatriots is less important than the immediate impression left behind that behavioral psychology had failed to take into account important influences on behavior. Textbooks began reporting that the Brelands’ work had revealed a sizable blind spot in Skinnerian theory — although Pettit (2010) suggested that this blind spot had always been there:

Certainly the initial reception of the studies of Davis, Cole, and Hunter… indicated that the raccoon did not mesh well with behaviourist theory…. The abandonment of the raccoon as a model was symptomatic of the neglect of [key] aspects of learning, of how behaviourism produced ignorance about them.

FOOT SOLDIER IN THE COGNITIVE REVOLUTION

The timing of the “Misbehavior” article couldn’t have been worse, because it followed close on the heels of Chomsky’s (1959) scathing review of Verbal Behavior, which, in the eyes of many, had already begun to invalidate the Skinnerian position. Additionally, around this time a number of animal researchers were growing restless regarding what they perceived as behaviorism’s failure to account for interesting data (which, in the spirit of Hunter’s, seemed hard to reconcile with “simple” conditioning). To be clear, they did not reject any explanation that behaviorists had advanced for the relevant phenomena so much as they perceived behaviorists as simply ignoring effects that didn’t fit their tidy world view.

All of this undermined confidence in the Skinnerian movement and thereby helped to advance the so-called Cognitive Revolution which, during the 1950s through 1980s, won many converts and reduced the influence of behavior analysis. Returning to the theme of animal learning, here’s a small example that captures the spirit of what happened. Studies of stimulus control were always part of basic behavioral psychology, but some doing the work viewed it as addressing processes, like perception and memory, that behaviorists (especially those in charge of certain journals) did not want to discuss. You can see an historical pivot point in the 1978 publication of a book called Cognitive Processes in Animal Behavior, which served as a kind of Declaration of Independence for the disgruntled investigators. The label animal cognition was swiftly adopted, and new organizations (like the Comparative Cognition Society) and journals (Animal Cognition and Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews) were established to focus on “human-like” psychological processes in a broad range of species. These are fully independent of behavior analysis, even though a behavior analyst would recognize many of the laboratory methods that are employed.

Counterfactual History

Now, with an eye on the current status of behavior analysis, let’s imagine an alternate universe in which things played out differently.

In the maelstrom that was early-1900s experimental psychology, what if the multi-species focus of Romanes had merged comfortably with the methodological rigor of Thorndike? What if a quest to make sense of “higher cognition” had employed a conceptually cautious, environmentally-focused theoretical framework? How might the Skinner of this alternate universe, benefitting from the experiences of investigators in the first three decades of the 20th Century, have proceeded differently than the one in our reality?

A key touchstone in the evolution of behavior analysis was 1953’s Science and Human Behavior, in which Skinner pivoted from lab work to offer his first large-scale account of complex human phenomena. But this was more than 40 years after the “raccoon uprising,” and Skinner presented no data (indeed, the book was criticized for being pure speculation). What might several decades of careful comparative experimental work on learning have contributed to the understanding of humans? And side note: Many of the seminal comparative researchers ended up gravitating to applied work. In our alternate reality, might applied behavior analysis have taken shape sooner than it actually did?

Had the science of behavior not been perceived as shying away from phenomena that, to the typical observer, defined what it means to be human, would it have better withstood the onslaught of the Cognitive Revolution? Indeed, would such a revolution even have been perceived as “necessary”? In this alternate reality, how might our contemporary scholarly societies and journals look different? Recalling Skinner’s description of behavior analysis as “we happy few” existing in an isolated “world of our own,” would our institutions be larger, healthier, bigger-tent operations?

Of course there are no definitive answers to any of this, but you know what they say about those who forget the lessons of history. Behavior analysis — not yet 100 years old, a mere toddler among the sciences — should take note of the raccoon as a symbol of missed opportunities to expand the boundaries of its inquiry. We cannot change the past but, going forward, a science still trying to make its mark should do everything possible to embrace whatever new opportunities come along to flex its muscles and stake claim to the many wonders of behavior.

Is the raccoon making a scientific comeback? See Postscript 6.

Footnote (added 11/16/24): For an example of how divisions tracing back to the early 1900s affected behavior analysis later on, see Postscript 8.

Postscript 5: The Business that Birthed the Miserly Raccoon

Breland and Breland established a company that used operant techniques to train animals to perform a variety of human-like behaviors, in many cases for advertisements and novelty displays. When I first moved to Illinois, in 1990, one of their displays, featuring a chicken that played tic-tac-toe versus customers [it rarely lost], was still operating at a rural amusement park not too far from me (and you can find numerous videos of tic-tac-toe chickens on YouTube).

The clip below shows some of the Brelands’ projects.

Postscript 6: “Why Raccoons are Re-Emerging from the Trash Bin of Brain Science”

According to PsycINFO, following near total disinterest in raccoons from roughly 1935 to 1950, an average of about 10 Psychology-relevant publications a decade appeared with “raccoon” as a subject from the 1950s to 2010s. A lot of that was neuroscience-focused. None of the work was in behavior analysis journals, however). Here’s one contemporary view on the potential of raccoons as a model of human behavior.

Postscript 7: Past is Prologue

Dewsbury (2003) provides an engaging story of how some of the clashing ideologies described here bubbled to the surface during a fraught two-year period in the late 1950s when two behavior analysts (Charles Ferster and Roger Kelleher) attempted to work at Yerkes’ primate research facility.

Postscript 8: The Historical Record

For what it’s worth, here’s an almost-certainly-incomplete chronological listing of raccoon-relevant publications, 1905-1935. Sources: PsycINFO and Google Scholar.

- Cole, L.W. (1907). Concerning the intelligence of raccoons. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, XVII(3, whole).

- Davis, H. B. (1907). The raccoon: a study in animal intelligence. The American Journal of Psychology, 447-489.

- Turner, C., & Augusta, G. (1907). Recent literature on mammalian behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 5(6), 195–205.

- Davis, H. B. (1908). Concerning the Intelligence of Raccoons. The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, 5(10), 278-279.

- Jennings, H. S. (1908). Recent work on the behavior of higher animals. The American Naturalist, 42(495), 207-216.

- Turner, C. H. (1908). Recent researches on the behavior of the higher invertebrates. Psychological Bulletin, 5(6), 190-195.

- Cole, L. W., & Long, F. M. (1909). Visual discrimination in raccoons. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 19(6), 657-683.

- Yerkes, A. W. (1910). Review of Visual discrimination in raccoons and Some experiments bearing upon color vision in monkeys. Journal of Educational Psychology, 1(6), 360–362.

- Shepherd, W. T. (1911). The discrimination of articulate sounds by raccoons. The American Journal of Psychology, 22(1), 116-119.

- Shepherd, W. T. (1911). Imitation in raccoons. The American Journal of Psychology, 22(4), 583-585.

- Cole, L. W. (1912). Observations of the senses and instincts of the raccoon. Journal of Animal Behavior, 2(5), 299-309.

- Hunter, W. S. (1912). A note on the behavior of the white rat. Journal of Animal Behavior, 2(2), 137-141.

- Watson, J. B. (1912). Literature for 1911 on the behavior of vertebrates. Journal of Animal Behavior, 2(6), 421-440.

- Gregg, F. M., & McPheeters, C. A. (1913). Behavior of raccoons to a temporal series of stimuli. Journal of Animal Behavior, 3(4), 241-259.

- Washburn, M. F. (1913). Recent literature on the behavior of vertebrates. Psychological Bulletin, 10(8), 318-328.

- Cole, L. W. (1915). The Chicago experiments with raccoons. Journal of Animal Behavior, 5(2), 158-173.

- Hunter, W. S. (1915). A reply to some criticisms of the delayed reaction. The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, 12(2), 38-41.

- Hunter, W. S. (1915). A reply to Professor Cole. Journal of Animal Behavior, 5(5), 406.

- Hunter, W. S. (1928). The behavior of raccoons in a double alternation temporal maze. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 35, 374-388.

- Gregg, F. M., Jamison, E., Wilkie, R., & Radinsky, T. (1929). Are dogs, cats, and raccoons color blind? Journal of Comparative Psychology, 9(6), 379-395.

- Munn, N. L. (1930). Pattern and brightness discrimination in raccoons. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 37, 3-34.

- McDougall, K. D., & McDougall, W. (1931). Insight and foresight in various animals—monkey, raccoons, rat, and wasp. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 11(3), 237-273.

- Bierens De Haan, J. A. (1932). Über das sogenannte “waschen” des waschbären(procyon lotor), nebst einigen bemerkungen über die formen und die bedeutung der tierischen spiele. [Concerning the so-called “washing” of the raccoon (Procyon lotor), with some remarks on the forms and significance of animal play] Biologisches Zentralblatt, 52, 329-343.

- Bierens De Haan, J. (1932). Über das suchen nach verstecktem futter bei einigen procyoniden und einem eichhörnchen. [On the searching for concealed food by some Procyonidae and a squirrel] Zeitschrift Für Vergleichende Physiologie, 17, 279-303.

- Elder, J. H., & Nissen, H. W. (1933). Delayed alternation in raccoons. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 16(1), 117-135.

- Kitzmiller, A. B. (1934). Memory of raccoons. The American Journal of Psychology, 46, 511-512. Bierens De Haan, J. A. (1934). Versuche über die verwendung der kiste als schemel bei einigen procyoniden, nebst einigen bemerkungen über das konkrete verständnis der tiere im allgemeinen. [Experiments on the use of the box as foot-stool by certain procyonids, with additional remarks about concrete understanding among animals in general] Zeitschrift für Psychologie Und Physiologie Der Sinnesorgane.Abt.1.Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 131, 193-216.