Previous posts in this series:

- #1 Învățare Mediată de Funcție într-o Fantomă (Operant Conditioning of a Ghost)

- #2 The Case of the Kung Fu Pigeon

- #3 Cumulative Graphs After and Before Skinner

- #4 “Porn,” Plungers, and Persistence at the Dawn of Human Behavioral Research

- #5 Assorted Gems and Curiosities, Courtesy of the Cambridge Center

Much of the present post is based on the following two sources. Both are recommended reading.

- Pettit, M. (2010). The problem of raccoon intelligence in behaviourist America. The British Journal for the History of Science, 43(3), 391-421.

- Boakes, R. (1984). From Darwin to behaviourism: Psychology and the minds of animals. CUP Archive.

I’m grateful to Dave Palmer and Susan Schneider for reviewing a draft of this post.

When you picture laboratory research in behavior analysis, you probably think of rats and pigeons in their iconic Skinner boxes.

Just as the salivating dog is the pop-culture face of classical conditioning, rats and pigeons are the poster species for operant learning. For example, textbooks on learning and behavior routinely display rats or pigeons in operant chambers to inform students about basic behavioral research. The rat also stars in the most famous cartoon about operant learning. Even behavior analysts often designate the rat as their symbolic standard bearer (inset; though see Postscript 1).

One obvious reason for all of this: Rats and pigeons were the workhorses of B.F. Skinner’s seminal research projects as described in The Behavior of Organisms and Schedules of Reinforcement, and though actual horses have been studied on occasion (not to mention humans and other novelty species), rats and pigeons remain the subjects of choice in basic operant research.

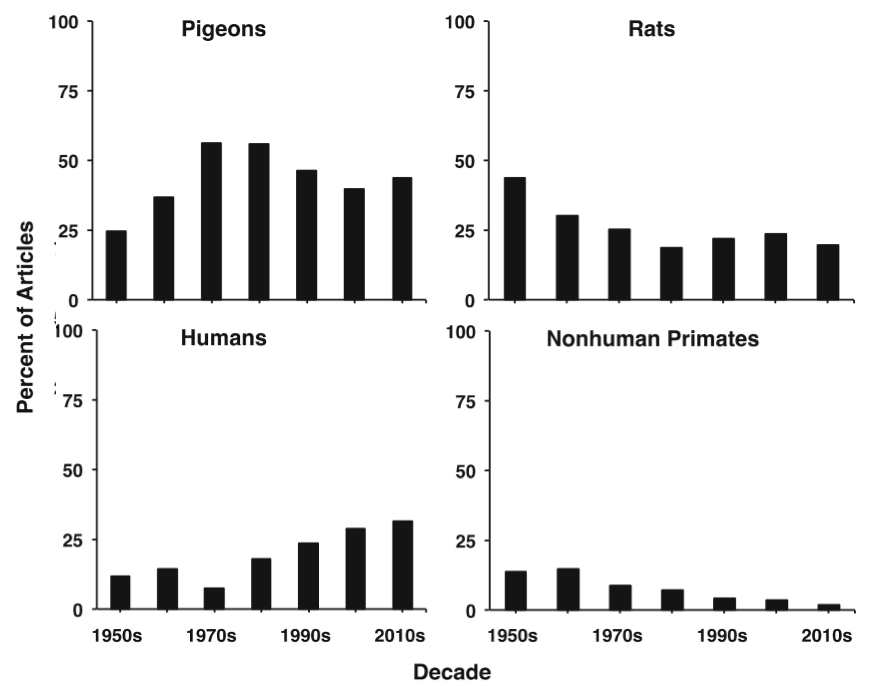

Don’t take my word for it. Zimmerman et al. (2015) examined the species studied in all articles published in Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (1958-2013) and found that, across decades, a reliable 60% to 75% or so focused on pigeons or rats (below). The review’s entire survey encompassed a grand total of 35,137 individual organisms, of which 20,993 (about 60%) were rats and pigeons [see Postscript 2].

Although these results won’t surprise anyone who’s ever cast a gaze toward basic behavioral research, they beg the question of how we arrived at this Rattus-Columbidae hegemony in the first place.

For part of the answer, you need to go waaay back. Behavior analysts tend not to be taught this in their specialized graduate training programs, but the history of scholarly inquiry into animal learning long predates Skinner. And 100 years ago or so, rat-pigeon dominance in learning research was far from a fait accompli.

In the period including and leading up to the early 1900s, researchers interested in the psychological characteristics of nonhumans examined all sorts of creatures. An influential 1880s book on animal psychology, for instance, included chapters on insects, fish, reptiles, and elephants. Thorndike studied cats and Pavlov dogs. Wolfgang Köhler tested “insight learning” in chimpanzees. And so on.

Among the early candidates suggested as a preferred lab subject was the raccoon. To explain why the raccoon attracted enthusiastic advocates, and why it ultimately failed to become our “lab rat” of choice, requires delving into a bit of history.

As befits the turbulent era to be examined, this is a meandering tale, but one worthy of your patience because, in saying a lot about raccoons it contextualizes the later emergence of behavioral psychology in a way you might not have considered.

Animal Learning Research Before Behaviorism: Competing Visions for a Science of Behavior

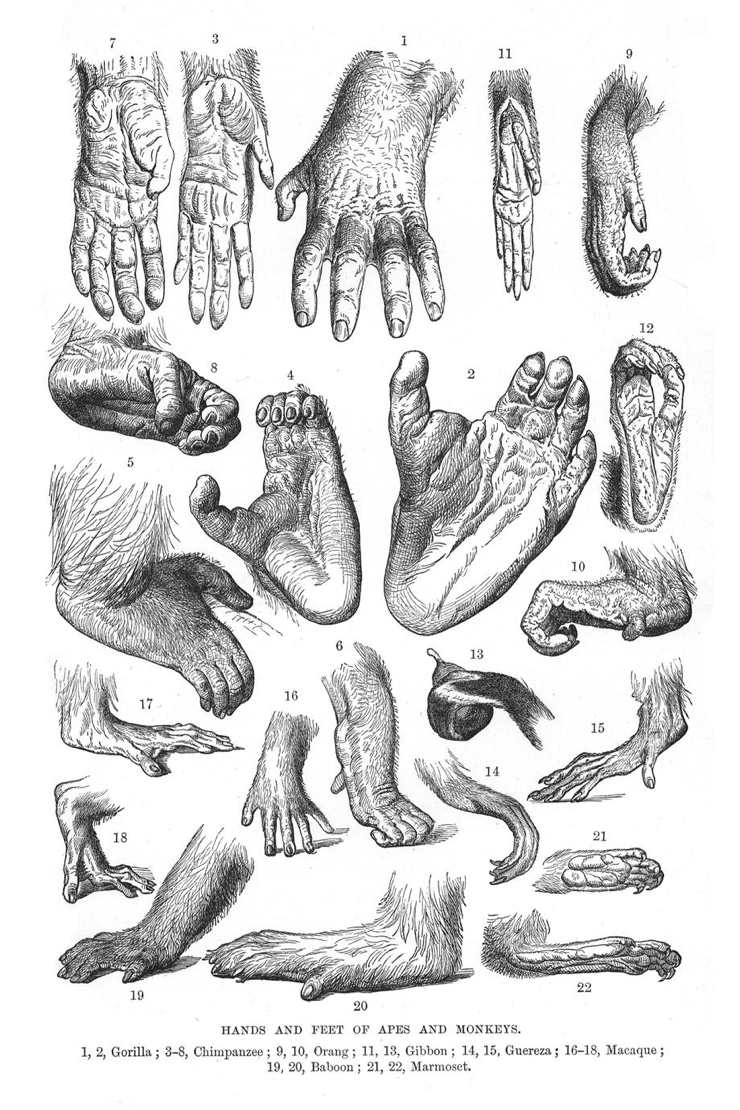

It’s hard to talk about “history” and “animals” without invoking Darwin. As the 1800s inched toward their close, the concept of evolution was firmly established in scientific circles, and with it the twin notions of interspecies generality and the conservation of characteristics across species. For example, note the obvious physiological similarity in the hands of numerous primate species [inset].

If body characteristics could be conserved across species, why not mental characteristics as well? Darwin had suggested as much, and as a result, as Robert Boakes wrote in his excellent book From Darwin to Behaviourism: Psychology and the Minds of Animals, “The animal mind had become an extraordinarily popular topic in the 1860s and 1870s. Countless letters flows in to scientific and popular journals, reporting striking observations of animals that suggested unexpected mental capabilities.”

Over the course of the next 50 years or so, several thinkers would propose that animals might be placed on an orderly continuum of mental abilities (with humans at the most capable end, of course). This fairly simple notion was, however, entangled with bitter controversies that would bear on the trajectory of Psychology as a discipline for some time to come, and indirectly shape what behavior analysis would turn out to be.

Although the debate of the era involved many of Psychology’s seminal scholars, let’s simplify and embody the times in two antagonists. On the one hand (see what I did there? hand? because of the inset? I’m hilarious!) was George Romanes, a late-life confidant of Darwin’s who in 1882 published Animal Intelligence, a collection of anecdotal observations of animal behaviors. For instance, Romanes relayed the second-hand story of two children “in the habit of feeding every morning with sugar an earwig, who they call ‘Tom,’ and which crawls up a certain curtain regularly at the same hour, with the apparent expectation of getting its breakfast.” Elsewhere in the book Romanes shared this account relayed to him of cows at a slaughterhouse:

The animal witnessing the process of killing, flaying, [etc.] repeated on one after another of its fellows, gets to comprehend to the full extent the dreadful ordeal, and as it mentally grasps the meaning of it all, the increasing horror depicted in its condition can be clearly seen. Of course some portray it much more vividly than others; the varying intelligence manifested in this respect is only another link which knits them in oneness. with the human family.

“Romanes,” Boakes observed in a celebration of the obvious, “had no hesitation in attributing to [animal behaviors] a wide range of complex mental processes, ranging from hypocrisy and deceit to… geometrical knowledge.”

On the other hand there was Edwin Thorndike, whose 1898 dissertation involved cats escaping from puzzle boxes to earn freedom or food. Having observed a lot of futile trial and error before his subjects managed an escape, Thorndike became convinced that learning in nonhumans was strictly the product of conditioning and involved no “higher cognitive” component. Thorndike’s position amplified Lloyd Morgan’s influential canon (from An Introduction to Comparative Psychology, 1894) which held that “In no case may we interpret an action as the outcome of the exercise of a higher psychical faculty, if it can be interpreted as the outcome of the exercise of one which stands lower in the psychological scale.”

To cut to the chase, in Thorndike we see a reliance on, and conservative interpretation of, objective experimentation that soon would feature prominently in both Watsonian and Skinnerian behaviorism. In Romanes we see considerable subjectivity in terms of both what counts as evidence and what it can be considered evidence for — problems that behaviorism was crafted to address.

And thus, as the 20th Century dawned, American Psychology (or at least the part of it that focused on animals) was an unstable hybrid venture. Thorndike’s rigorous laboratory methods caught on in a big way, but Romanes’ fascination with animal intelligence spawned attention to an increasing number of species. This was the dawn, or perhaps the hazy pre-dawn twilight, of comparative psychology — a topic on which none other than J.B. Watson would author a book in 1914. At the uncomfortable nexus of the era was Morgan’s canon, according to which strict experimental methods made perfect sense BUT an evolutionary continuum of human-like mental capabilities did not. Why? Because the canon had become entangled with the view that human “higher cognitive” abilities were the result of language. Animals did not exhibit language, ergo, “because nonhumans lacked language they could not possess reason; nonhumans therefore were different in kind from humans” (Petit, 2008, p. 400).

Enter the Raccoon

As researchers sought to branch out from Thorndike’s cats in their search for human-like mental abilities, one creature seemed like a natural target: the raccoon, which was well familiar to American scientists because it’s indigenous to most of North and South America. Americans had long hunted raccoons for pelts and meat and even kept them as pets (Postscript 4). In the latter case, in 1904, Zoologist W.T. Hornaday declared the raccoon “one of the most satisfactory carnivorous pets that a boy can keep in confinement” (quoted in Pettit, 2010, p. 397), and one of the more famous boys of the early 20th Century, President Calvin Coolidge, famously shared the White House for a time with his beloved Rebecca the Raccoon:

In both Native American mythology and colonial lore, raccoons were seen as possessing human-like intelligence and personality characteristics like deviousness, curiosity, mischievousness, and playfulness. They surely are easy to anthropomorphize because of their human-esque hands (inset), whose dextrous fingers wash food and intricately manipulate objects. Their facial markings recall a burglar’s mask, and they seem to get into everything in ways many other species do not [see Postscript 3; also, for some fun photos showing just how “human” animal behaviors can appear, see here].

So when those proto-comparative American experimentalists went looking for a creature that was intellectually intermediate to humans and the “lower” animals, raccoons seemed a perfect fit.

Unlike other species that receded in the face of human expansion, the raccoon was an evolutionary success story. It was an animal that adapted and flourished along the borderlands of humanity. It existed simultaneously as the foodstuff of the poor and valued commodity for clothing, an agricultural pest and a treasured companion, a brute beast and crafty trickster. This liminal status informed the understanding of the raccoon among comparative psychologists and shape its use as an experimental organism. For psychologists the animal seemed both to offer a natural object of investigation and to display an arguably human intelligence (Pettit, 2010, p. 398).

Two researchers emerged as early champions of the raccoon. In 1907, both Lawrence Cole and H.B. Davis published studies on raccoon performance in puzzle boxes that were inspired by Thorndike’s cat research but modified to employ various kinds of mechanisms to effect an escape [see Postscript 4]. Both men were critical of Thorndikian research that used methods not tailored to the test subject’s phylogeny, and both believed that “species-blind” methods underestimated mental capacity.

Both Cole and Davis concluded that, among nonhumans, only primates eclipsed the intelligence of raccoons. Davis claimed that raccoons were unusually curious, by which he meant:

…In psychological terms, spontaneous attention and the instinct to investigate. Without it active intelligence is out of the question. The raccoon is an animal which displays this quality in a high degree. Its curiosity contributes to the development of its intelligence while at the same time it often becomes a source of serious lesson teaching.

Cole emphasized that, in puzzle boxes, raccoons often did not require the lengthy trial and error of Thorndike’s cats. He believed that they utilized mental imagery, and maintained that “it is difficult to find a motor performance too difficult for them.” Together, Cole and Davis led a charge against organizing animal learning experiments around any single species. Their work was praised by many leading lights of the day, including Robert Yerkes and Herbert Spencer. J.B. Watson even said that the “results of Cole’s study of the intelligence of the raccoon probably constitute the most important contribution to comparative psychology that has yet been made by a single investigator.”

Exit the Raccoon

And yet, despite such hoopla, in the literature of just a few decades later you’ll find little evidence that this work ever existed. Cole and Davis aren’t cited and raccoons are scarcely discussed. To find out why, and how this bears on behavior analysis, check out…

Part 2 of “The Brief, Tumultuous Trash-Panda Interlude in Animal Learning Research”

Postscript 1: The Rat as the Public Face of Behavior Analysis

Whether it’s good public relations to lead with the rat as symbolic standard bearer for behavior analysis could be debated. One of my favorite popular press articles — which I often assign to new students — is “Like a Rat” by Alan Kazdin and Carlo Rotella in Slate. The article does a nice job of discussing, for the uninitiated, how many essential components of child therapy trace to basic research on animal behavior. And yet Kazdin and Rotella allow that

Talking about the underpinnings of psychology in animal research tends to make parents uneasy, even upset—not because they fear that the animals were mistreated but because of what they think it implies about their children. “You’re saying my kid’s like a rat? You’re saying my kid’s not complex and unique? What about this picture he drew of Spider-Man sobbing in a rainstorm?” When they’re outraged, insulted, and indignant, people tend to be less receptive to whatever it is that those who upset them have to say, so there’s a sound practical reason for psychologists not to provoke parents needlessly.

Words to the wise, perhaps.

Postscript 2: On the Prevalence of Rats and Pigeons in Basic Research

Esoteric note of interest to few: The reason why the percentage of JEAB articles using pigeons and rats exceeds the percentage of total subjects that were pigeons and rats is a straightforward side effect of an EAB trend in which between-groups designs featuring humans have become more prevalent over time. Between-groups experiments tend to have more subjects than within-subjects experiments. If you examine only single-subject experiments I think you’ll find that % of articles and % of subjects line up pretty well.

Postscript 3: On Pet Raccoons

Postscript 4: Types of Release Mechanisms in Davis’ Raccoon Puzzle Boxes

These were employed singly and in various combinations. Reproduced from Davis, H. B. (1907). The raccoon: a study in animal intelligence. The American Journal of Psychology, 447-489.