I want a house with a crowded table / And a place by the fire for everyone – The Highwomen (2019)

“Crowded Table” was co-written by Hemby and fellow revered songwriter Lori McKenna, with additional contributions from Carlile. The Meaning Behind The Highwomen’s Inclusive “Crowded Table”

Invited blog by:

Among behavioral educators, the topic of similarities between behavior analytic pedagogies and Universal Design for Learning is gaining interest (Travers, 2016). Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a research-based educational framework aimed at designing learning environments that meet the diverse needs of all learners (Cast, 2004). While UDL has foundations in cognitive theories of learning, a difference in conceptual backgrounds should not dissuade behavior analysts from opportunities to support our learners with diverse needs. Travers wrote, “teachers do not care about which theory best explains the facts; they want practical strategies they can put to use in their classroom on Monday morning.”

Inspired by an eloquent statement made by Diller and Lattal (2008), that emphasizes embracing similarities over differences, our team has approached UDL to find common ground in the context of higher education. We have sought to “build bridges” and collaborate with instructional designers and other professors outside of behavior analysis. Despite our philosophical differences we share a common goal to support all learners. Critchfield (2018) emphasized the power of storytelling, therefore, we would like to share our team’s story of fruitful collaboration with UDL supporters. We will then provide a brief overview of UDL and highlight Traver’s (2016) insights into similarities between behavioral education and UDL approaches before we offer some of our own.

Our Story

At our university, our team of ABA faculty have been fortunate to collaborate with a phenomenal instructional designer, Aura Lippincott, who is a tireless supporter of UDL (Lippincott, 2022). Our collaboration began when Aura caught news of our students’ significant increase in pass rates for the BACB certification exam. She invited us to do a presentation and share our asynchronous online course design for our university faculty teaching community. This occurred during the pandemic which involved a rapid transition from learning on-campus to the online environment. During our presentation, Aura noted the similarities between UDL and the teaching practices we were describing. She introduced our team to UDL and our fruitful collaboration began.

What is UDL?

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a research-based educational framework aimed at designing learning environments that meet the diverse needs of all learners (CAST, 2024). Developed from insights in cognitive neuroscience, UDL seeks to reduce barriers to learning by providing flexible options for how students engage with content, access information, and demonstrate their understanding. A core philosophy of UDL is to design inclusive learning experiences from the start, rather than accommodating lessons for individuals. The framework is structured around three main principles: multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple means of action and expression.

Key Principles of UDL

Multiple Means of Engagement: Engagement addresses how learners are motivated and sustained throughout the learning process. UDL encourages educators to offer different ways to tap into learners’ interests, challenge them appropriately, and keep them engaged. This may involve providing choices in learning activities, fostering collaboration, or creating opportunities for self-reflection.

Multiple Means of Representation: Learners perceive and comprehend information in different ways. UDL promotes offering various ways to present information, such as using multimedia, text, audio, visuals, or hands-on materials. By providing content in diverse formats, educators can ensure that all students, regardless of sensory or cognitive differences, can access and understand the material.

Multiple Means of Action and Expression: This principle emphasizes offering students multiple ways to demonstrate what they have learned. Instead of expecting every student to perform in a uniform way, UDL encourages flexibility in assessments. For example, students might show their understanding through writing, speaking, drawing, or creating videos, depending on their strengths and preferences.

Through strategic application of these principles, UDL seeks to cultivate learner agency, that is “purposeful & reflective, resourceful & authentic, strategic & action-oriented.” (CAST, 2024).

The UDL framework emphasizes that barriers to learning are often the result of inflexible design of learning experiences, rather than deficits within the learners themselves. UDL is about flexibility and inclusivity, shifting the focus from a one-size-fits-all model of education to one that values variability and seeks to accommodate learner differences. By designing educational experiences that anticipate diverse needs, UDL helps create an equitable learning environment where every student has the opportunity to succeed.

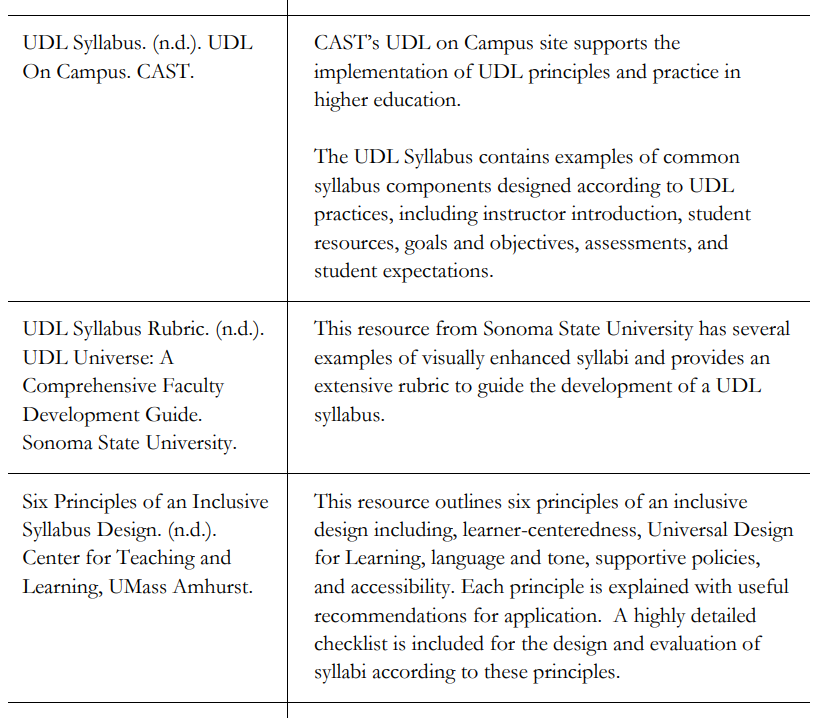

In the table below, Lippincott (2022) offered UDL resources that may be helpful for syllabus evaluation and redesign efforts. Resources include before/after examples of syllabi components that have been redesigned to improve learner-centeredness, increase inclusivity, and reduce barriers that may inhibit student engagement in the course community.

Similarities between UDL and Behavior Analytic Pedagogies

Travers’ (2016) compared and contrasted behavior analytic and UDL approaches to learning. He pointed out differences in philosophy rather than in practice. In terms of practical similarities, many of our antecedent based strategies for early learners (e.g., alter instructions, provide choices, allow breaks, increase motivation, see Figure 3 based on Miltenberger, 2006) align well with UDL despite differences in conceptual background.

To expand on Traver’s excellent insights, the placement of students with disabilities in inclusion settings has increased over the past 30 years (Giangreco, 2020) and there are no signs of this trend of educating students of all abilities in a classroom of their peers slowing down. There are many advantages of an inclusive classroom for teachers and students, but it does not come without its challenges. Inclusive classrooms require that individual educators are prepared to meet the varying needs of all students, regardless of ability. The UDL framework seems tailor made for the inclusive classroom with its proactive, flexible, and adaptable approach to teaching helping teachers to accommodate the abilities and needs of all learners. Behavior analysts are well suited to create individualized teaching plans tailored to meet all learners needs. There are several examples of behavior analysts examining application of UDL in inclusive classrooms. In one such example, Gauvreau et al. (2023) describe the use UDL by co-teachers to promote inclusion during circle time in a pre-school classroom setting for diverse learners. Behavior analysts have also contributed to the literature on inclusion and UDL as it relates to School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS) and designing programs that including all students including those with extensive needs. The most exciting thing about the combination of UDL and ABA with inclusive teaching is that gone are the days where a child with disabilities was “included” in a classroom simply by their presence in the room with their peers. UDL offers a framework to include all children in truly meaningful ways and behavior analysts can help teachers design individualized assessment and treatment plans while measuring progress to identify what’s working and what’s not working for each student so that the strategies can be modified as needed.

Also, it is important to recognize that one barrier often encountered by BCBAs working in schools is buy-in to our procedures (Max & Lambright, 2022). While there are several contributing factors to challenges with buy-in one of these challenges is terminology. A language barrier can often exist between behavior analysts and educators (Cihon et al., 2016). Each group is taught a specific way of talking about learning, and differences in this language can sometime hamper effective collaboration. UDL provides a framework within which behavior analysts could better disseminate ABA based procedures to educators. First, UDL provides behavior analysts with a shared vocabulary they can use in schools. The language used in UDL is that taught to educators in their preparation programs and would therefore already be familiar to them (Moore et al. 2018). For example, UDL emphasizes using multiple means of engagement, identifying what motivates students and tapping into student interest (CAST, 2024). Behavior analysts will likely immediately see the parallels to incorporating choice, identifying reinforcers, and manipulating motivating operations. Second, the Key Guiding Principles of UDL can be used by behavior analysts as a way of organizing and sharing our own basic principles. For example, Multiple Means of Engagement matches our principles of reinforcement, while Multiple Means of Action and Expression parallels our field’s emphasis on individualized intervention and technology of generalization. UDL can act as a bridge between our technologies and implementation in the classroom.

Behavioral education has much to offer UDL in kind. The UDL Framework presents a systematic way for designing learning environments that meet the diverse needs of all learners, but it is only a framework. UDL offers basic guidelines but does not provide procedures to implement these guidelines. Behavior analysis offers evidence-based strategies that we can train educators to use to execute the recommendations offered in the UDL framework. For example, the UDL framework emphasizes sustaining student effort. ABA has a wealth of research on reinforcement systems (e.g., Doll et al.,2013; Maggin et al., 2011). UDL encourages teaching students’ skills like empathy (Law et al., 2024) and restorative practices (e.g., Anderson, 2022). ABA offers procedures such as multiple exemplar training and video feedback that have been found effective in teaching these complex skills (e.g., Kern Koegel et al., 2016; Sivaraman, 2017). In this same way, the data collection technologies used in ABA may also be advantageous for use within UDL. The UDL framework encourages assessing student progress in a variety of ways. From a feasibility standpoint this may present educators with a challenge when it comes to developing consistent ways of measuring student progress. ABA’s emphasis on ongoing data collection and the myriad of data collection procedures that exist in our field could be an asset in this case (e.g., Lerman et al., 2011). Behavior analysts can work with educators to develop data collection procedures that are effective and most importantly feasible within the classroom.

ABA may also help to make implementation of the UDL Framework more efficient. One challenge facing educators is the pervasive issue of fads in general and special education. Educators often find that their classrooms become testing grounds for these fads, wasting valuable time, and progress for students (Kozloff, 2005). Although packaged as effective and lauded by districts, “experts”, and other educators these fads have no empirical evidence or experimental research demonstrating their effectiveness (Zane, 2010). Here again ABA’s emphasis on evidence-based procedures offers the opportunity for effective collaboration. The use of behavioral science can make the designing of inclusive classrooms more efficient by providing educators with procedures that are empirically supported replacing strategies that are attractive, but ultimately ineffective.

Attitudes Toward Collaboration

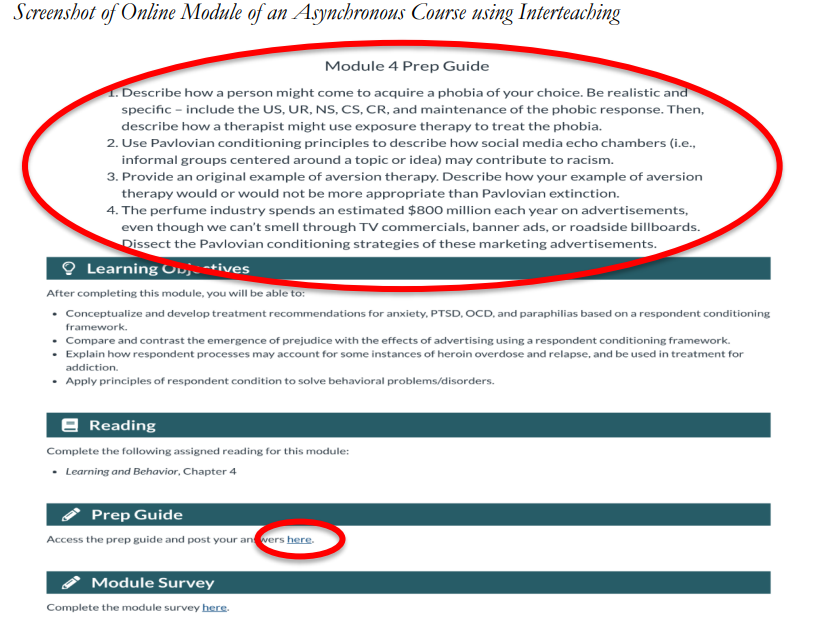

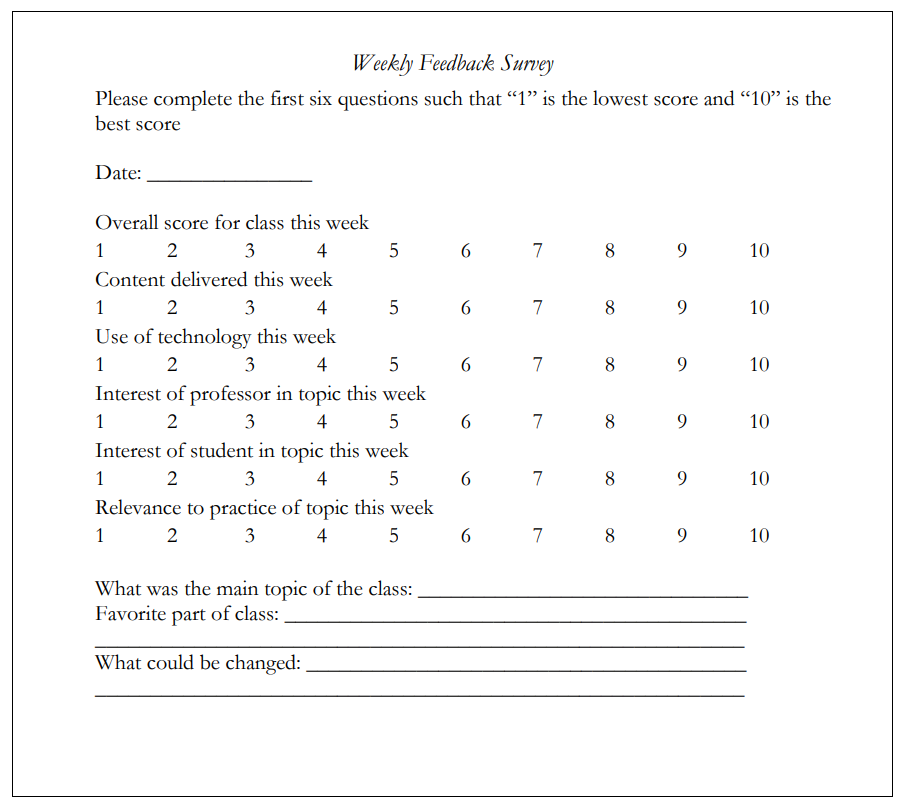

All of us have found our collaboration as ABA faculty and UDL supporters valuable and beneficial and recommend viewing such collaboration as akin to joining a new practice area. It is important to highlight that we strove to follow Alligood and Gravina’s (2021) wise advice when joining a new area of practice. Our ABA faculty have our background in applied practice and translational human operant research. We did our best to make ourselves useful by sharing our resources to professors in need that aligned with UDL in terms of multiple means of engagement (e.g., earning points for active student engagement with lecture videos and associated data: Kuhn et al. 2022; discussion boards: Alligood, 2022) and Multiple Means of Action and Expression including student created lectures. In addition, we shared weekly student feedback surveys to supplement end of semester student feedback (Pritchard & Wine, 2022).

Perhaps, most importantly we shared an inside look at our course design before we ever uttered any behavior-analytic terminology. What is exciting is that our teaching community now views us as learning experts rather than instructors of a specific discipline. As a result, we can openly share Skinner’s Technology of Teaching (1968) and recent advances in behavioral education (interteaching: Krebs et al., 2021) with the UDL teaching community. In kind, the UDL community has us to support diverse learners across cultures and different points along the neurodiversity and mental health continuum (e.g., Houck & Dracobly, 2023; Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022). We are thankful to have had the opportunity to create a two-way street that allows our teaching practices to be shaped by UDL and vice versa. As a result, we published an free, open educational resource (Howard, 2019) that represents a fruitful collaboration between behavioral educators and UDL supporters (for an overview, see Elcoro et al., 2022). Ultimately, like a consumer behavior analysis approach (Rafacz, 2019), these collaborations serve not only to benefit the faculty but also our students and the future clients they will serve with compassionate and effective treatment.

References

Alligood, C. A. (2022). Supporting meaningful student outcomes in the online environment. In Brewer, A., Elcoro, M. & Lippincott, A. (Eds.), Behavioral pedagogies and online learning (pp. 37-52). Hedgehog Publishers. Retrieved from Behavioral Pedagogies and Online Learning

Alligood, C. A., & Gravina, N. E. (2021). Branching out: Finding success in new areas of practice. Behavior

Analysis in Practice, 14, 283-289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00483-2

Anderson, C. A. (2022). Integrating behavioral science and rightful presence to support diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in online learning environments. In Brewer, A., Elcoro, M. & Lippincott, A. (Eds.), Behavioral pedagogies and online learning (pp. 184-191). Hedgehog Publishers. Retrieved from Behavioral Pedagogies and Online Learning

CAST (2024). Universal design for learning guidelines version 3.0. Wakefield, MA: Author. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Cihon, T. M., Cihon, J. H. and Bedient, G. M. 2016. Establishing a common vocabulary of key concepts for the effective implementation of applied behavior analysis. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9, 337–348. Retrieved from https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/161

Critchfield, T. S. (2018). An emotional appeal for the development of empirical research on

narrative. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 41, 575-590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-018-0170-9

Diller, J. W., & Lattal, K. A. (2008). Radical behaviorism and Buddhism: Complementarities and

conflicts. The Behavior Analyst, 31, 163-177. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392169

Doll, C., McLaughlin, T. F., & Barretto, A. (2013). The token economy: A recent review and evaluation. International Journal of basic and applied science, 2(1), 131-149.

Elcoro., M., Brewer., A., & Lippincott. A. Introduction. (2022). Open Educational Resource: Behavioral Pedagogies for Online Learning. Editors: Brewer, A., Elcoro, M. & Lipincott, A. Retrieved from Behavioral Pedagogies and Online Learning

Gauvreau, A. N., Lohmann, M. J., & Hovey, K. A. (2023). Circle is for everyone: Using UDL to promote inclusion during circle times. Young Exceptional Children, 26(1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/10962506211028576

Giangreco, M. F. (2020). “How can a student with severe disabilities be in a fifth-grade class when he can’t do fifth-grade level work?” Misapplying the least restrictive environment. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 45(1), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1540796919892733

Houck, E. J., & Dracobly, J. D. (2023). Trauma-informed care for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: From disparity to policies for effective action. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 46(1), 67-87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-022-00359-6

Howard, V. J. (2019). Open educational resources in behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12, 839-853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00371-4

Jimenez-Gomez, C. and Beaulieu, L. (2022), Review of Multiculturalism and Diversity in Applied Behavior Analysis, edited by Conners and Capell. Jnl of Applied Behav Analysis, 55: 639-644. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.903

Kern Koegel, L., Ashbaugh, K., Navab, A., & Koegel, R. L. (2016). Improving empathic communication skills in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 921-933. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-015-2633-0

Krebs, C. A., Kuhn, S. A., Brewer, A. T., & Diller, J. W. (2021). Using interteaching to promote online learning outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Education, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-021-09434-5

Kozloff, M. A. (2005). Fads in general education: Fad, fraud, and folly. In Controversial therapies for developmental disabilities (pp. 181-196). Routledge.

Kuhn, S. Krebs, C., Diller, J., & Brewer, A. (2022). Active student responding to increase student engagement in online asynchronous college courses. In Brewer, A., Elcoro, M. & Lippincott, A. (Eds.), Behavioral pedagogies and online learning (pp. 77-95). Hedgehog Publishers. Retrieved from Behavioral Pedagogies and Online Learning

Law, V., Turner, L. B., & Brewer, A. T. (2024). Using Peer-Led Behavioral Skills Training to Teach Trainees Active and Empathic Listening Skills in a Virtual Environment. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-024-00954-w

Lerman, D. C., Dittlinger, L. H., Fentress, G., & Lanagan, T. (2011). A comparison of methods for collecting data on performance during discrete trial teaching. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 4, 53-62. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF03391775

Lippincott, A. (2022). Syllabus design to foster community in online courses. In Brewer, A., Elcoro, M. & Lippincott, A. (Eds.), Behavioral pedagogies and online learning (pp. 136-155). Hedgehog Publishers. Retrieved from Behavioral Pedagogies and Online Learning

Kozloff, M. A. (2005). Fads in general education: Fad, fraud, and folly. In Controversial therapies for developmental disabilities (pp. 181-196). Routledge.

Maggin, D. M., Chafouleas, S. M., Goddard, K. M., & Johnson, A. H. (2011). A systematic evaluation of token economies as a classroom management tool for students with challenging behavior. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 529-554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.05.001

Max, C., & Lambright, N. (2022). Board certified behavior analysts and school fidelity of applied behavior analysis services: Qualitative findings. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 68(6), 913-923. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/20473869.2021.1926854

Miltenberger, R. (2006). Antecedent interventions for challenging behaviors maintained by escape from instructional activities. In J. Luiselli (Ed.), Antecedent assessment & intervention, (2nd ed.) (pp. 101-124). Baltimore: Brookes.

Moore, E. J., Smith, F. G., Hollingshead, A., & Wojcik, B. (2018). Voices from the field: implementing and scaling-up universal design for learning in teacher preparation programs. Journal of Special Education Technology, 33(1), 40- 53. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264341773229

Pritchard, J.K., & Wine, B., (2022). The use of feedback in higher education. In Brewer, A., Elcoro, M. & Lippincott, A. (Eds.), Behavioral pedagogies and online learning (pp 53-62). Hedgehog Publishers. Retrieved from Behavioral Pedagogies and Online Learning

Rafacz, S. D. (2019). Review of Organizational Behavior Management: The Essentials, edited by Byron Wine and Joshua K. Pritchard: 2018; Orlando, FL: Hedgehog Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-019-00236-9

Sivaraman, M. (2017). Using multiple exemplar training to teach empathy skills to children with

autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(4), 337- 346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-017-0183-y

Skinner, B. F. (1968). The technology of teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts

The Highwomen. (2019). Crowded table [Song]. On The Highwomen. Low Country Sound/Elektra Records.

Travers, J. C. (2016, March). Where UDL and applied behavior analysis intersect: Organizing environments to support student learning. Paper presented at the Annual UDL-IRN Summit, Towson University, Maryland. Retrieved from (PDF) Where UDL and Applied Behavior Analysis Intersect: Organizing Environments to Support Student Learning

Zane, T. (2005). Fads in special education: An overview. Controversial therapies for developmental disabilities, 197-214. Routledge.