There’s a rather breathless claim making the rounds in child development circles which says, in effect, that interactive experience isn’t required for children to learn language. This claim contradicts decades of conventional wisdom tracing back (at least) to Hart and Risley’s (1995, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of American Children) landmark study that found language development to be closely correlated with amount of high quality language experience (Note: Here “high quality” means basically that caregiver and infant take frequent turns talking and/or reacting to about things infants are interested in).

A whole bunch of valuable early-intervention programs (like Head Start) have been predicated on the belief that kids need to be actively involved with language. These programs aim to enrich early experiences (particularly involving language) to prepare disadvantaged preschoolers to enter school on equal language footing with their more advantaged peers. And the exciting Thirty Million Words Project aims to extend that early leg-up to newborns and infants by teaching new parents some powerful but simple-to-implement “languaging” skills.

If recent research on child language acquisition is being interpreted correctly, all of this effort is completely unnecessary!

What’s Observed and What’s Claimed

But as far as I can tell, it’s NOT being interpreted correctly. To explain, we need to examine what really took place in the research.

To give credit where it’s due, the research is a well-meaning effort to break out of the WEIRD trap, in which sweeping generalizations about human nature are derived from studies that focus on people from places that, in global actuarial terms, are atypical: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. For example, it’s a descriptive fact that Hart and Risley didn’t study the language experience of “all children;” or even “American children.” They studied a few dozen Kansas children who culturally and otherwise may or may not be like children elsewhere.

With this in mind, it’s certainly noteworthy that researchers have catalogued the language experiences of young indigenous children in decidedly non-WEIRD places, like remote Papua New Guinea. The general finding is that these children are constantly in earshot of language, but it is rarely directed at them so, in contrast to Western children, they get few opportunities to verbally respond. As a result, such children get only a fraction of the “high quality” verbal interaction from which American children supposedly benefit.

Let’s take a careful look under the hood of a representative study on the early language experiences of Tseltal Maya children in the Mexican state of Chiapas. Tseltal mothers carry their children in “backpacks” or slings during pretty much all waking hours. Moms rarely speak to their kids; however, unlike, many American children, Tseltal children are in a position to overhear adult interactions all day long. According to tthe researchers, the prevailing idea of “more is better” in early verbal interactions…

… Predicts that Tseltal infants should have minimal lexical knowledge, given that they are rarely the direct recipients of speech. Evidence that infants in this context and developmental period possess such lexical knowledge would thus be a challenge to prevailing theory.

And yet the researchers found that Tseltal children, aged 5-16 months, had language abilities on par with those of Western children. Concludes one account of the study:

The results show that human infants are clearly capable of learning language through observation, suggesting that talking directly to young children is not a requirement.

And a 2022 essay, directed at findings like this, proposed that infants in different cultures may acquire language via totally different mechanisms: in WEIRD nations via the “massed experience” model described by Hart and Risley, and elsewhere via simply listening.

Problem 1

But before you burn your copy of Hart and Risley, note two serious logical problems with this conclusion. The first is the assumption that anybody ever imagined that interactive language experience is the sole mechanism by which WEIRD kids learn to talk. It has long been known, for instance, that before infants produce anything approximating formal language — before they are capable of sophisticated verbal give-and-take — they show evidence of learning from the talking that’s around them. For instance, once infant “babbling” emerges (around 6 months), speech sounds from caregivers’ native language quickly begin to predominate. During the same period, infants show increasing perceptual sensitivity to native-language sounds and reduced sensitivity to sounds that are not part of caregiver speech. There’s even reason to think that language learning starts in the womb — hence the claim that, “Fetuses cry in the accent of their parents.” This claim is based on the prosidy (intonation patterns) of newborns. According to the linked article (an interesting read):

[Researchers] collected and analysed the cries of 30 German and 30 French newborns from strictly monolingual families. They found that the French newborns tended to cry with a rising – low to high – pitch, whereas the German newborns cried more with a falling – high to low – pitch. Their patterns were consistent with the accents of adults speaking French and German.

Since these babies had basically zero post-birth language experience, the prosodic aspects of their cries must have been learned in the womb.

Now, there are several different ways to interpret such evidence, but they all hinge on infants “caring” about what sounds are, and are not, part of the local language milieu. Maybe, for instance, as per the theories of linguist Noam Chomsky, they have some kind of innate language module in the brain that evolution has shaped to process language. Most linguists don’t take Chomsky literally these days. But on a general level, to suggest that humans have evolved special adaptations that support language is no more provocative than saying horses have evolved adaptations that support running.

More to the point, It’s also likely that the earliest responses to language are shaped by conditioned reinforcement. A number of studies have shown that preverbal infants respond differentially to, and imitate, speech sounds that are paired with already-effective reinforcers (in behavior analysis research, the relevant experience has been referred to as “stimulus-stimulus pairings”). And of course caregivers are the source of most reinforcers that infants experience [nutrition, warmth, etc.], so caregiver speech sounds become paired with those reinforcers. That’s a recipe for producing conditioned reinforcers. Because humans attend to reinforcers, and manufacture them when possible, this may be enough to account for why very young humans differentially tune into and produce native-language speech sounds. I’m therefore not surprised that very young Tletsal children who hear a lot of language would show some language competence.

Problem 2

The second problem is that the available data don’t actually show that listening is sufficient to build a capable talker. All of the relevant evidence comes from infants roughly 18 months and younger, and few of us would call the typical 18-month-old a “capable talker.” Sure, some dramatic, mind-boggling things happen when child language first emerges, but let’s be real: Nobody is scheduling an 18-month-old to give a TED Talk. Those first months are when the rudiments of language take shape, but language learning is an extended process, as every developmental psychologist knows and as Hart and Risley showed long ago.

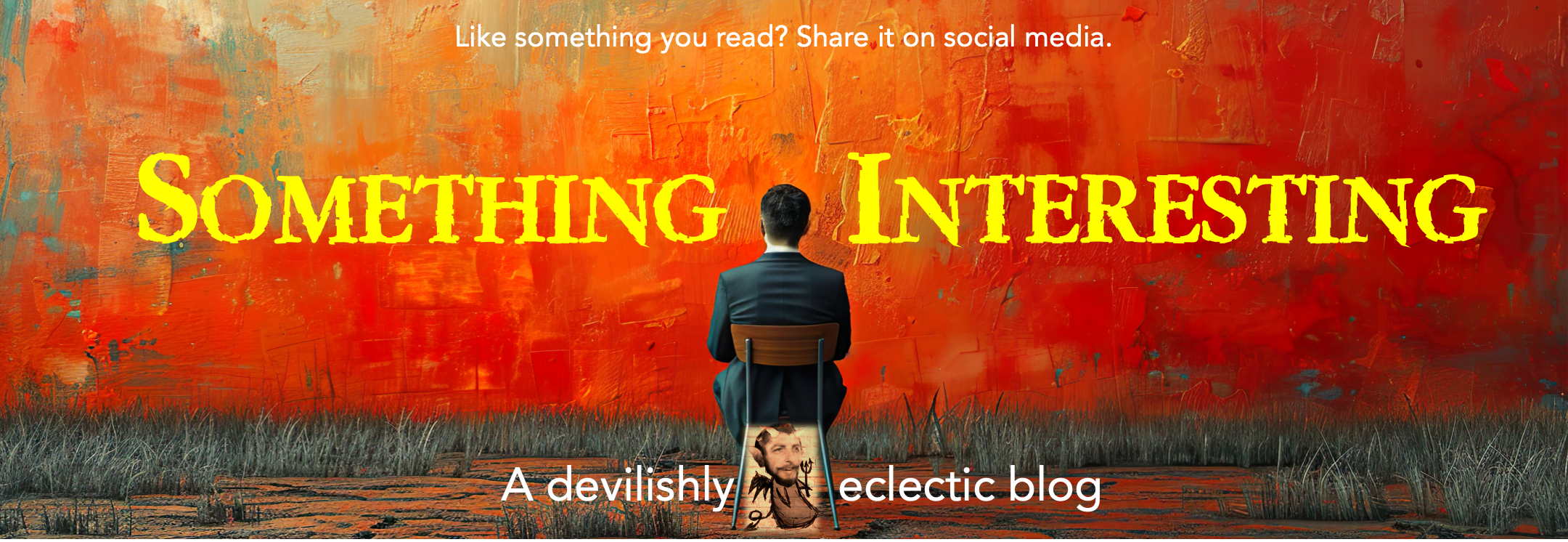

With that in mind, below is a summary of key findings from Hart and Risley. Of present interest is the right panel, which shows vocabulary growth in three groups of children who had different amounts of interactive language experience (that’s shown in the left panel). By age 3, there were big vocabulary differences between the groups — and Hart and Risley also linked language experience to IQ and later school success. But look carefully at the right panel, specifically at where the groups are around 18 months of age: There is almost no discernible difference between groups.

In other words, a lot of the exciting stuff attributed to interactive language experience kicks in a bit later than 18 months of age. In a way, it doesn’t really matter what drives language development prior to that. The take-home message from Hart and Risley remains: Talking to your child, often and in particular ways, is closely tied to language development as it accelerates toward adult-like competence.

And when considering that acceleration, let’s not forget the lesson of Ernst Moerks’ pioneering research, which carefully analyzed of what happens when mothers interact with kids around age two. Moerk worked from audiotapes made by a researcher named Roger Brown, who thought he saw no explicit “teaching” at work and therefore endorsed Chomsky’s notion that children are endowed with innate language sensitivities that allow them to learn from simply being around language. But when Moerk carefully coded the interactions in Brown’s recordings, he found massive, unmistakable evidence of the three-term operant contingency in action. Prompts and consequences were everywhere, and readers of this blog know well the immense power of operant processes to shape behavior.

Note: If you have a serious scholarly interest in language development, then there’s no substitute for a careful reading of Moerk’s work, starting with the article linked above. Be forewarned, however: That paper is densely written and many people find it difficult to wade through. If you’re looking for a more casual appraisal, see the Postscript, which is a quick(ish) summary/excerpt of the paper that I created for my undergraduates.

Show Me the Data That Really Matter

So here’s the take-home. In order for cross-cultural research to challenge Hart and Risley, it would have to show that non-WIERD children (a) have listening-only language experiences well beyond 18 months; and (b) thereafter continue to match the language prowess of Hart and Risley’s participants with the richest interactive language experiences.

I doubt (a) very seriously. This is just a guess, as I’ve seen no data on the language experiences of Tseltal children after 18 months. But as every parent knows, give a kid a little bit of language and they start demanding that you converse with them. I therefore find it implausible that the Tseltal language experience remains completely passive much after about 18 months.

I’m also skeptical of (b). I’d really like to see how language proficiency in older Tseltal children compares to that of WEIRD kids, but a quick search turned up no relevant data.

Note: Here I want to be careful not to fall blindly into the WEIRD trap. What counts as “proficient” could vary across cultures. Let’s recall that the inspiration for Hart and Risley’s research, and for early intervention programs like Head Start, traces to how children function in Western-style academic settings. It’s entirely possible that Tseltal children develop verbal repertoires that are different but make them effective in Tseltal culture. After all, different cultures probably create different language demands, and child rearing practices likely evolve to meet those demands. I have no evidence that the Tseltal people are anything less than great at being Tseltal (and I’m also not saying that my WEIRD language-acquisition history would make ME good at being Tseltal). I merely suggest that, were you to place Tseltal children into a culture where reading and writing and Western-style persuasion and verbal elaboration are critical, those kids could face challenges tracing to their listening-only early language experience. [This is a testable proposition — for instance, by looking at standardized academic achievement scores of children in Mexico’s nine Tseltal-majority towns, though a quick internet search didn’t turn up any relevant data. In general, indigenous children’s test scores tend to lag behind those of other Mexican students, but that’s too much of an aerial view to inform the present discussion.] The irony here is that if what counts as “proficient” varies across cultures then quantitative cross-cultural comparisons like that of the Tseltal study are essentially meaningless.

To summarize, all I’m saying is that before we attempt to totally re-think child language acquisition, it’s critical to examine what the “non-WIERD” research on language acquisition really shows. The available data are pretty interesting — enough that I devoted a whole post to them. But more research is needed. Followup studies must examine whether verbal proficiency at preschool to adult levels can really come from listening only. And should findings like that appear, I’ll be the first to admit I’m wrong. But until that happens, beware the claim that children can develop sophisticated verbal behavior simply by listening. That claim currently is grounded in shaky evidence, and it would be a deep, dark shame if a mis-reading of evidence were to dampen efforts to spread the gospel about the importance of early language experience and disseminate evidence-based approaches to enriching it.

Postscript

This is a heavily-edited excerpt of the following article, from a research program that makes an important contribution to our understanding of the role of learning in child language development.

DISCLAIMER: This was my effort to make a difficult read accessible to undergraduates with no background in behavior analysis or linguistics. In service of brevity and clarity, I took lots of liberties with the text: simplifying wording, adding a bit of explanation, and omitting a great deal. Aside from the Abstract and Table 1, which are reproduced verbatim below, do not assume I’m presenting Moerk’s exact words. For full detail and for quotation purposes, see the original article. Any misrepresentation or oversimplification of Moerk’s work is entirely my fault.

ABSTRACT

Selections from a large longitudinal data set of verbal interactions between a mother and her child are presented. Two sets of three-term contingency sequences that seemed to reflect maternal rewards and corrections were noted. Both the antecedents as well as the immediate consequences of maternal interventions are presented to explore training and learning processes. The observed frequencies of three-step sequences are compared to those expected based upon Markov-chain logic to substantiate the patterning of the interactions. Behavioral conceptualizations of the learning process are supported by these analyses, although their sufficiency is questioned. It is suggested that maternal rewards and corrections should be integrated with perceptual, cognitive, and social learning conceptualizations in a skill-learning approach to explain the complexity of language transmission and acquisition processes.

This report presents results from a research program that deals with verbal interactions of a mother and her child and their functions for language transmission and acquisition. The focus is upon training (by mothers) and learning (by infants).

The approach can be contrasted with Noam Chomsky’s popular psycholinguistic theory, which proposes that young children have innate knowledge about language and thus acquire it after mere exposure to others talking. Chomsky claims this is possible because humans possess a “language organ” (Caplan & Chomsky, 1980; Chomsky, 1975) that “knows” how to produce language in the same way as the stomach “knows” how to produce stomach acid. There is no empirical evidence that such an organ exists, and the present research program (e.g., Moerk, 1986, 1989) assumes that no innate linguistic knowledge is needed, with language acquisition explainable fully on the basis of learning.

The present research re-examines the classic work of Roger Brown, who generously gave access to his data on mother-infant verbal interactions for reanalysis. Brown argued that evidence of maternal teaching and child learning learning are nowhere to be found in his data (Brown, 1973; Brown & Hanlon, 1970), and was therefore inclined to view language learning as innately driven.

The approach used here was to record various kinds of utterances made by mothers and their infants, and then use the Markov chain model to see if they occurred together more often than would be expected by chance. For instance, imagine that Mother Response X occurred in a dyad’s data with a probability of .20, and Infant Response Y occurred with a probability of .10. A Markov chain is simply the product of those probabilities, or .20 X .10 = .02. If the sequence X-Y occurred with a probability higher than .02, that would be evidence of nonrandom pairing, that is, a potentially meaningful pattern of mother-child interaction.

Of special interest were patterns suggestive of operant learning in mother-child verbal interactions. In operant learning, behavior is changed by its consequences, that is, events which follow after it. These consequences can also make behavior situation-specific, that is, linked to, or prompted by, certain stimulus conditions. The result: A three-term contingency in which behavior depends on antecedent stimuli and consequences depend on behavior. Considering stimuli that come before behavior (antecedents), behavior, and consequences that follow after behavior, if mothers are actively teaching language then we would expect this kind of sequence to happen in mother-child interactions more often than by chance:

|

Antecedent Stimulus |

Behavior | Consequence |

| Mother speaks | Child speaks |

Mother speaks |

Also of importance is a sequence in which the child speaks, mother responds, and the child reacts in a way showing learning based on maternal influence.

|

Antecedent Stimulus |

Behavior | Consequence |

| Child speaks | Mother speaks |

Child speaks |

The specific kinds of mother and child utterances that were coded were based on traditional categories in linguistics and related fields (see Table 1).

METHOD

The child whose verbal interactions with her mother are analyzed is “Eve,” one of the 3 subjects studied by Roger Brown (e.g., Brown, 1973). Eve and her mother were observed in their home, engaging in normal activities of everyday life. Eve was 18 months old at the beginning of the observation, and she was observed for less than 1 year, up to her 28th month of age. Of the samples collected by Brown, all odd-numbered ones were selected; 2 hr of recording for each of these samples were analyzed in detail.

Roger Brown’s research team audiorecorded the data in the home and transcribed them later. These transcripts were coded by the present author and two trained research assistants. Multiple interrater and repeat-reliability tests were performed during the entire period of coding. The reliabilities for most of the categories were in the 80% to 90% range.

See Table 1 for the types of verbal responses that were coded for approximately 10,000 utterances of mother and child. Then the frequency of occurrence was determined for various three-step sequences that seem relevant to the three-term operant contingency. A total of 51,766 three-step sequences were recorded.

For each possible sequence, the question arises whether it is merely a random occurrence (if mother and child talked independently, uninfluenced by each other, some of their utterances would sill happen one after the other). This report therefore focuses on comparing observed frequencies (how often a given sequence occurred in two hours of mother-child talk) with how often it would be expected to occur by chance.

Expected frequency of a given sequence was calculated using the Markov chain model, which multiplies the observed frequencies (probabilities) of the individual responses in a sequence. For simplicity, imagine a two-behavior sequence consisting of Mother Response X (observed probability = .20 per minute) and Child Response Y (observed probability = .10 per minute). A Markov chain is simply the product of those individual probabilities, thus .20 X .10 = .02 per minute. That equates to 2.4 occurrences in a two-hour interaction sample. If the X-Y sequence were observed substantially more than 2.4 times during the sample, this would suggest nonrandom pairing, that is, a potentially meaningful pattern of mother-child interaction.

RESULTS

Two major topics are emphasized in the three-term contingency patterns to be presented: (a) reinforcement, which is denied or at least disregarded in much of the psycholinguistic literature, and (b) maternal expansions (Table 1), in which mother imitates the preceding utterance of the child to indicate agreement (this can be assumed to function as reinforcement). Expansions, by adding elements that were omitted, also show where the child made mistakes of omission. In this latter perspective they also fulfill a corrective function, providing the information (model) from which the child can learn the correct form. For each of these two topics, the child’s response to the maternal feedback also will be documented.

Analyses focus on sequences (involving Table 1’s mother/child response categories) that occurred a minimum of 5 times in the samples. Because the interest is in whether teaching sequences occurred more often than expected by chance, results focus on comparing the actual and expected frequencies of relevant sequences.

Reinforcers and Their Consequences

In accordance with the behavioral conceptualization of the three-term contingency patterns of stimulus-response-reinforcement, Table 2A presents a pattern wherein the mother produces the first utterance (stimulus), the child responds to this, and the mother hen provides a reward or reinforcer.

Reward and reinforcer are conceived in the sense of Thorndike (1911) and his law of effect and are operationally defined as a maternal ”yes, ” “yeah,” “right,” or an equivalent response. These maternal responses occurred on average about every 2 min — potentially a great deal of positive feedback. How maternal reinforcement factored into the child’s experience is obvious in Table 2A: Many linguistic skills were first modeled by the mother; they were more or less directly imitated by the child; and then were reinforced by the mother. For all 31 different sequences of this type, observed frequencies greatly surpassed those expected by chance.

Reward and reinforcer are conceived in the sense of Thorndike (1911) and his law of effect and are operationally defined as a maternal ”yes, ” “yeah,” “right,” or an equivalent response. These maternal responses occurred on average about every 2 min — potentially a great deal of positive feedback. How maternal reinforcement factored into the child’s experience is obvious in Table 2A: Many linguistic skills were first modeled by the mother; they were more or less directly imitated by the child; and then were reinforced by the mother. For all 31 different sequences of this type, observed frequencies greatly surpassed those expected by chance.

If the patterns in Table 2A represent operant reinforcement, then after maternal approval the reinforced child response ought to re-occur. Table 2B evaluates this prediction. Shown are three-term patterns consisting of a child utterance, maternal “reinforcement,” and what the child does next. A reinforcement hypothesis predicts repetition of all or part the original type of utterance. Eleven child-mother-child sequences occurred more often than expected by chance, and 9 of them showed the expected child behavior outcome.

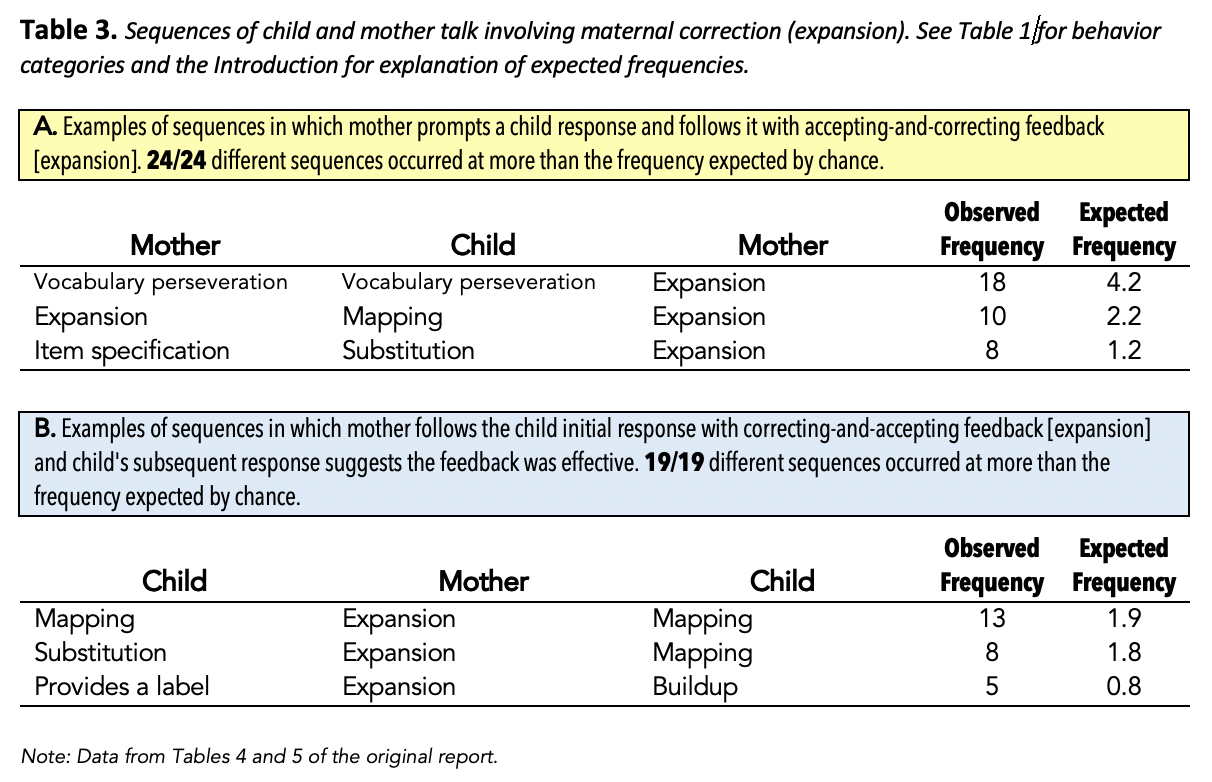

Rewards Combined with Corrections and Their Impact

Maternal expansions are utterances that repeat a preceding child utterance, retaining close similarity but adding items that were omitted by the child. They thus serve a double function: The imitative repetition is rewarding, but the insertion of omitted elements is simultaneously corrective and informative as to the preferred form of the utterance. Table 3A shows the observed and expected frequencies of several three-step sequences that fit this “accepting-and-correcting” pattern, all of which occurred more often than expected by chance. These results are consistent with what would be anticipated if mothers are consciously fulfilling a teaching function.

The purpose of teaching is to drive learning, and Table 3B provides a glimpse of what happens in child responding following sequences like those listed in Table 3A. These contingency patterns also support the motivating character of maternal expansion. It induces the child to continue with identical or very similar verbal behavior (Eve’s next response has a structure like that of the mother’s last utterance or incorporates information from the mother’s expansion), which in turn will receive positive feedback in most instances.

DISCUSSION

The present findings are descriptive — the data were collected in a naturalistic environment — and not an experiment that can verify cause-and-effect. Additionally, he present analyses identify processes that could lead to lasting language learning, but they focus on a brief period early in life and thus cannot demonstrate learning over extended periods. Only longitudinal data could do this. However, based on what is known about operant learning, the kinds of interactions demonstrated by Eve and her mother would be expected to fuel language learning at all stages of child language acquisition.

Interpretations focusing on operant learning are based on plausibility: sequences that occur more often than chance, that fit with how learning is known to occur. The child’s responses to maternal utterances often incorporated linguistic improvements that had been modeled by the mother and suggested that the ties between stimulus and response classes had been reinforced. The results therefore suggest maternal teaching and child learning that are inconsistent with Chomsky’s (1959) assumption that mere exposure to language is enough to power child language acquisition.

This is not to rule out a role for imitation-from-example (e.g., Whitehurst & De Baryshe, 1989) in language acquisition. However, the ability to imitate itself may be learned. Baer and Sherman (1964) showed that young children did not spontaneously imitate until the act of copying a model’s behavior had been reinforced many times, with the resulting skill referred to as generalized imitation. It is evident from the present findings that Eve’s imitations often were reinforced, providing a potential basis for the learning of generalized imitation.

REFERENCES

- Baer, D. M., & Sherman, J. A. (1964). Reinforcement control of generalized imitation in young children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 1, 37-49.

- Brown, R. (1973). A first language: The early stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brown, R., & Hanlon, C. (1970). Derivational complexity and order of acquisition in child speech. In J. R. Hayes (Ed.), Cognition and the development of language (pp. 11-53). New York: Wiley.

- Caplan, D., & Chomsky, N. (1980). Linguistic perspectives on language development. In D. Caplan (Ed.), Biological studies of mental processes (pp. 97-105). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1959). Review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. Language, 35, 26-58.

- Chomsky, N. (1975). Reflections on language. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Moerk, E. L. (1986). Environmental factors in early language acquisition. In G. J. Whitehurst (Ed.), Annals of child development, Volume 3 (pp. 191-235). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Moerk, E. L. (1989). The LAD was a lady and the tasks were ill-defined. Developmental Review, 9, 21-57.

- Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal intelligence, experimental studies. New York: Macmillan Co.

- Whitehurst, G. J., & De Baryshe, B. D. (1989). Observational learning and language acquisition: Principles of learning, systems, and tasks. In G. E. Speidel & K. E. Nelson (Eds.), The many faces of imitation in language learning (pp. 251-276). New York: SpringerVerlag.