Back in October of 2023, I wrote that artificial intelligence appeared to have some strange ideas about behavior analysis, at least as indicated by images generated by the tool DALL-E in response to phrases borrowed from our discipline. I talked about these images in terms of relational frames, or the stimulus relations that DALL-E has formed around words from our disciplinary vocabulary.

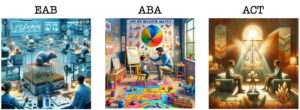

In my previous post I described two patterns in DALL-E’s pictorial output. In the first, phrases like experimental analysis of behavior (EAB) and applied behavior analysis (ABA) tended to result in images laden with unintelligible verbiage and curious diagramming (below, two leftmost images). When applied behavior analysis yielded images of people, they tended to be adults in curious poses, like the man jabbing a pencil into his eye (below, center).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) fared somewhat better, yielding images appearing to show caring human interactions — but with two strange wrinkles (above, two rightmost panels): The images often had an unsettling religious tone, and the heads of the people were often disfigured or even melting. As I wrote about the latter case:

While I have always found that wading through the idiosyncratic language of ACT makes me FEEL as if my face is melting, DALL-E treats this as a physical effect.

It’s possible that these images are meaningless. Perhaps they show a nascent AI system struggling to generate images based on phrases it has no experiential basis for interpreting. Or maybe there was a method to DALL-E’s madness. Regarding “gibberish” images like those shown above I wrote:

I chuckled at this, in a nervous sort of way, thinking of recurring discussions about how our technical language befuddles people who aren’t behavior analysts. It is in fact often gibberish to them. And of course it’s true that we behavior analysts TOTALLY dig diagrams and flow charts and such (if you doubt me, pick up any random publication focusing on derived stimulus relations).

In any case, I’m pleased to report that today, behavior analysis seems to claimed a measure of respect from artificial intelligence. Recently Derek Reed, of the Institutes for Behavior Resources, sent me the AI-generated images shown below. You’ll quickly notice that the images approximate photorealism — that is, in important ways they seem to capture key aspects of EAB and ABA and ACT.

At least a couple of things are going on here (plus, see Postscript 1). First, Derek used ChatGPT Pro which, compared to the free version of DALL-E I used, is a far more sophisticated tool in terms of both its graphic capabilities and its underlying AI architecture. Based on these features alone we might expect more representative images. Second, AI learns. As it digests more and more digital information, its stimulus relations update and evolve. In this case, it’s entirely possible that today AI simply understands us better.

And that’s a good thing, because whether any of us likes it or not, AI tools are out there in the world and people are using them with increasing frequency to educate themselves and others — in much the same way as they once used old-school Google searches. What AI thinks about behavior analysis, therefore, will influence what a lot of people think about behavior analysis (see Postscript 2).

I’ll close by noting one curious thing. Although the newer portrayal of ACT avoids face-melting, it retains distinct religious overtones. This feels like the punch line to some joke that I hesitate to construct. What’s being insinuated here? Maybe a zealousness, or even cultishness, among ACT practitioners? In the image above, I half expected to glimpse Steve Hayes, wearing a priest’s collar, peeking out from behind the stained glass window. Or maybe I should check my cynicism — maybe AI views ACT’s effects as akin to a spiritual awakening? For now, ChapGPT Pro isn’t saying. Maybe the best we can do is check back in a few months to see how it portrays us then.

Postscript 1

I must also note that, in prompting images from ChatGPT Pro, Derek provided a bit more linguistic context than I did with DALL-E (see his verbatim prompts below). This might make a difference in the output.

- “experimental analysis of behavior” in a laboratory setting

- “applied behavior analysis” in a therapy session context

- “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy” in a therapeutic session context

Postscript 2

Regarding the quality of AI’s “knowledge” about behavior analysis, an example: On January 29, 2024, Darrel Bostow posted the following on the History of Behavior Analysis listserv. Darrel asked an AI tool, “What was the effect upon our culture brought about by B. F. Skinner’s book Beyond Freedom and Dignity?” The answer was judged as not too awful by respondents on the list.

It appears there might be a confusion in your question. B.F. Skinner’s book “Beyond Freedom and Dignity” was published in 1971, and its impact on culture was significant, but it did not have a universally positive reception. Skinner, a behaviorist psychologist, argued against the concept of free will and autonomy, suggesting that human behavior could be understood and controlled through scientific principles of behaviorism.

Skinner proposed that society should focus on using positive reinforcement and behavior modification techniques to shape behavior, rather than relying on punishment. He suggested that traditional notions of freedom and dignity were impediments to achieving a more orderly and controlled society.

The book sparked controversy and criticism, with many individuals and intellectuals opposing Skinner’s ideas. Critics argued that his vision threatened individual autonomy, personal freedom, and the ethical considerations of treating humans as mere objects to be manipulated.

While Skinner’s ideas had some influence on certain areas of psychology and education, they did not lead to a widespread societal shift toward the kind of behaviorism he advocated in “Beyond Freedom and Dignity.” The book’s impact on culture was more in terms of stimulating debate about the nature of freedom, ethics, and the role of science in shaping human behavior. However, it did not fundamentally alter cultural values or practices on a large scale.