In my part of the world, it’s mid-summer. The days are growing shorter and to-do lists are growing infinitely longer as university people begin to cultivate course plans and plot their various professional commitments for another academic year. There’s no better time to discuss that plague of professional life, overcommitment. Because the truth is…

…Or, more specifically, I submit, you may, to your own detriment, be doing too much of the wrong kind of work.

Now, don’t misunderstand. If you want to get ahead in a professional career, you need to work very hard, because people who get more done are those who tend to get noticed, receive new opportunities, and earn career advancements (they also tend to contribute more to the discipline!). That’s as it should be, but there’s an art to deciding what to work on.

Before we get to that, let’s take a peek at what a less-is-more strategy might look like. In May of 2021, four researchers came to the realization that they were working harder and harder while enjoying work less and less. As described in Nature, they responded by doing the unthinkable. They resolved to work less: “[Our discussion about overcommitment] led one of us to throw down the gauntlet: …Facing pandemic and career burnout, this member whimsically suggested we make a game out of saying no by challenging ourselves to collectively decline 100 work-related requests.”

Before we get to that, let’s take a peek at what a less-is-more strategy might look like. In May of 2021, four researchers came to the realization that they were working harder and harder while enjoying work less and less. As described in Nature, they responded by doing the unthinkable. They resolved to work less: “[Our discussion about overcommitment] led one of us to throw down the gauntlet: …Facing pandemic and career burnout, this member whimsically suggested we make a game out of saying no by challenging ourselves to collectively decline 100 work-related requests.”

Whimsy quickly turned into a formal professional development project:

There is an old adage that you manage what you measure. We often say yes by default, so tracking our decisions introduced a moment for us to pause and make a conscious choice…. [Thus] we spent a year tracking and reflecting on our decisions to say no…

Tracking ‘no’s inspired us to record other things. We logged completed tasks to counteract impostor syndrome, kept a running count of active projects and tracked how we were spending time each day. This helped us to limit the number of projects that we took on or the hours that we spent working.

But the researchers reported that it wasn’t easy to strategically say NO, as conditioned emotional responses and conscientious good intentions often got in the way:

Over our year of no, we routinely noted feelings of guilt. We worried that we were letting down colleagues, not doing our ‘fair share’ or failing to live up to the privilege we hold as fully employed researchers and mentors. We wanted to be kind, helpful and available, even if doing so left us personally overwhelmed. Each member struggled to turn down invitations…. For one of us, it was hard to say no to taking on another graduate student although she was already serving on six students’ committees. Another struggled to decline an early-morning presentation that conflicted with her family’s morning routine, although she was the only parent at home that week. We even found it difficult not to volunteer for service roles or shiny opportunities that we were not directly asked to take on. In myriad ways, we saw how our cultural conditioning as women, academics and public servants contributed to our difficulty with setting boundaries.

When they did say NO, the researchers found that they had more time to work on things they really valued, and they became happier and more productive professionals.

When they did say NO, the researchers found that they had more time to work on things they really valued, and they became happier and more productive professionals.

To understand just how radical this project was, you first have to take an objective look at how people with advanced degrees tend to spend their time.

Crazy Is As Crazy Does

Once in a while I try to describe my work to acquaintances who aren’t academics. They are flabbergasted when they learn that various entities expect me to do all of the following (and much more), even though I don’t get paid for any of it:

- evaluate journal manuscripts (peer review)

- participate in committees and boards of professional organizations

- attend and address professional conventions (this actually costs me money, as travel funds are scarce at my university)

- answer emergency emails (with “emergency” defined as “whatever the sender deems it to mean”) in the evenings and on weekends

- work on course preparation and research during the winter “vacation” and the summer months in which I’m not employed by the university

- write blog posts for ABAI 😅

And when I tell them how many hours a week I work — in order to get stuff like this done around my daily responsibilities in the classroom, the lab, and my department — their jaws drop. Because in their jobs, duties are well-defined and tied directly to evaluations and advancement (just as OBM types would recommend). Most of them work 40 hours a week, not 50, or 70, and they not only go home after an eight-hour day, but are expected to by their employers.

And when I tell them how many hours a week I work — in order to get stuff like this done around my daily responsibilities in the classroom, the lab, and my department — their jaws drop. Because in their jobs, duties are well-defined and tied directly to evaluations and advancement (just as OBM types would recommend). Most of them work 40 hours a week, not 50, or 70, and they not only go home after an eight-hour day, but are expected to by their employers.

Although the details of your job may be different, I’m guessing the general scenario is familiar: You end up doing a lot of stuff that’s implicitly expected of you but falls outside your job description and/or isn’t compensated.

As an example consider a colleague who runs a grant-funded, university-affiliated clinic to train autism practitioners. In addition to teaching and supervising graduate students, she spends an extra 10 to 20 hours a week making sure that our university (which is not renowned for administrative acumen) prepares staff contracts correctly, handles budgeting matters properly, and approves day to day expenses that nominally were already approved in the grant budget. She writes quarterly reports, attends meetings with the granting agency, and makes appearances at various community events related to autism. Outside of business hours, she dashes to WalMart several times a week for cleaning and office supplies, reinforcers, and toilet paper (none of which the university contributes despite taking a hefty chunk of the grant for “indirect costs”). Oh, and if a kid pukes in a treatment room or clogs a toilet, guess who’s pulling late-night duty dealing with that?

Nobody understands her job any more than they understand mine. And the reason they don’t is, of course, because these jobs don’t make sense. They’ve been shaped by pathologies with which we are so familiar that we forget to question them.

Rules and Contingencies

How do we arrive at such insane professional routines and identities? For one perspective, I recommend a post on the Experimental History blog (check out “Excuse me but why are you eating so many frogs?“), which does a decent good job of capturing this problem: The professional world is saturated with implicit rules concerning what a successful individual “should” be doing.

Graduate school, it turns out, is part training (which teaches you how to do things) and part brainwashing (which persuades you to do more of those things than anyone else). The latter is the byproduct of all sorts of reasonably innocent forces. For instance, your role models, your mentors, are incredibly productive, real top-of-the-distribution people, and the implicit message is that you need to become like them. Even in the most collegial programs, you’re also competing with your hard-working peers for limited advancement opportunities. None of this is pathological per se, because once you hit grad school you’re in the big leagues where the competition is fierce and not everyone will become a superstar. So you do have to work very hard to get ahead.

Yet just how hard is not obvious. Many of us live in a world of variable, poorly-discriminable professional contingencies — the type of contingency that is well known for maintaining response rates far in excess of what’s necessary to generate reinforcers.

And layered atop those poorly-discriminable contingencies is something sinister that I call the GOODBAD (that stands for Good-Of-Our-Discipline Beliefs And Dogma).

The genesis of the GOODBAD is simple and insidious. People choose to specialize in things they love. They want what they love to prosper, which makes them willing recruits for work that “advances our discipline.” Most behavior analysts I know would do almost anything to help behavior analysis succeed. So it has always been. Our mentors inherited the GOODBAD from their mentors and, intentionally or otherwise, passed it along to us.

Oh, and by the way: Humans are good at generalization, and so extend the GOODBAD mentality to all sorts of smaller arenas than “our discipline” (e.g., “good of the agency,” “good of the department” etc.). As a result, find any group of professionals numbering more than a handful, and chances are they want you to do something for them “for free.”

To get a concrete sense of what the GOODBAD is all about, re-read that quote at the start of this post, from researchers struggling to limit their commitments. Then do a quick inventory of your own professional commitments. For each one you identify, ask yourself: Who benefits most from my efforts?

Here’s a personal example. Over the years I’ve done a lot of editorial work for journals. In the process, I’ve helped a lot of authors get their papers published in a form that’s likely to reach and inform as many readers as possible. I’ve also helped wealthy publishing corporations make fat profits on journals by relying on creative teams that cost them virtually nothing (i.e., authors, reviewers, and editors are all essentially volunteers).

And what have I gotten in return? Well, I’ve had to set aside my own lab work, ignore my students, defer writing my own papers, work a lot of nights and weekends, give up time with my family, skimp on exercise routines, and periodically take abuse from authors who don’t perceive my efforts as helpful. Because editorial work isn’t much valued by the reward system at my university, it doesn’t really help me earn raises or promotions. Yeah, there’s a certain diffuse professional notoriety that comes with being part of an editorial team, but, to be brutally objective, at the end of the day you can’t eat or spend that and it certainly doesn’t make you a healthier, better balanced human being.

The “take one for the team” message of the GOODBAD is an emotional distraction from this kind of practical analysis. To see the GOODBAD in operation, check out a recent essay on the imbalanced contingencies inherent in publishing. While acknowledging that people who do editorial work derive limited direct benefits (“Virtually no one in the history of professional science has been promoted or meaningfully rewarded because they provide stellar reviews of others’ work”), the essay still passionately defends the GOODBAD‘s central premise: It maintains that the vitality and survival of science depend on people volunteering their time, and deems it “selfish” to ask, “What’s in it for me?”

“Should” and “More Fun”

To summarize thus far, the GOODBAD says that every professional should engage in behaviors that boost our discipline, and those who don’t will be regarded poorly by other professionals. This sounds innocent enough until you consider that, amongst the varied pathologically destructive verbal rules that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) was created to combat, some of the most pernicious incorporate the precise components just mentioned: (a) they specify what an individual “should” do, (b) in order to avoid rejection by the peer group. Because humans are inherently social animals, group acceptance and belonging are powerful motivators. People will do most anything to avoid exclusion from the “tribe,” including what cultural conditioning says they should, even if that distances them from other reinforcers.

Which brings us to the heart of the GOODBAD conundrum which, appropriately enough, since we’ve invoked ACT, applies contextually. Different people find different things reinforcing, and there certainly are times when should duties are enjoyable. For example, a colleague told me that his term as ABAI President — during which he put his own career on hold in order to better the association and serve member interests — was the best three years of his life. This illustrates that it’s absolutely wonderful when doing something both enriches your life and has positive effects on other members of your tribe. We get into trouble, though, when should duties benefit ONLY other members of the tribe. I spent more than ten years in ABAI governance, and I am proud of many things that were accomplished during this time (e.g., the founding of Behavior Analysis in Practice and the creation of the Skinner Lecture series at the annual convention, to mention two). But in contrast to my colleague, I didn’t have a lot of fun. I found administrative work exhausting and stressful. Almost daily, I was sad about the things I couldn’t do while I was attending to ABAI’s interests [that I somehow hung in there for a decade highlights what a tenacious hold the GOODBAD can have on us].

Look, everyone has different reinforcers. In every instance, it’s rational, not selfish, to acknowledge that time and response opportunities are finite, such that engaging in one behavior rules out engaging in others. If, in a given instance, your reinforcers align with the GOODBAD, great. If not, think carefully about how you spend your time, no matter how other people think you should.

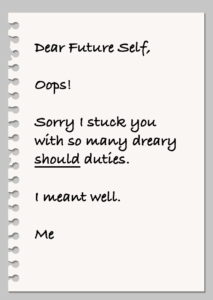

Ah, but if only it were easy to tell, in the here and now, while agreeing to new commitments, what will make your future self happy!

Unfortunately, we learn early on to say YES to just about everything without properly considering the ramifications. What grad school taught me, and a lot of people I know, is that all professional responsibilities are equally important when it comes to sizing up career progress. Lab time? Duh. Clinical work? Can’t skimp on that. Teaching? That pays the bills. Journal articles and conference presentations? Absolutely required. Professional service? Check. And in all of the categories, we come to believe that more is always better.

With this kind of thinking, pretty soon the mission of learning that brought you to graduate school becomes hopelessly intertwined with a frantic chase for lines on a curriculum vitae. And before you know it, the GOODBAD has you in its clutches.

Counting accomplishments, without distinguishing which ones are most valuable [and everything here depends on your personal definition of “valuable”] replicates the fallacy of an old Calvin and Hobbes cartoon, in which Calvin waxes poetic about the contributions to his exercise program of a heart rate monitor. When Hobbes is skeptical that quantifying everything is really necessary, Calvin explains:

If your numbers go up, it means you’re having more fun.

But of course, with apologies to Calvin, when your numbers go up the only certain thing is that you’re working harder. Rather than having fun, you may instead be sacrificing your most cherished reinforcers and setting yourself up for burnout.

Just Say NO… If You Dare

So there you have it: My advice to know your reinforcers, and when they don’t align with GOODBAD-inspired opportunities, to resist committing to things that serve others more than you.

Easier said than done, of course, as discovered by those four researchers who launched the “Say NO” project. Recognizing how hard it is to say NO, they proposed that, to combat years of cultural conditioning, you approach each new opportunity by asking these five questions (my comments in italics):

Easier said than done, of course, as discovered by those four researchers who launched the “Say NO” project. Recognizing how hard it is to say NO, they proposed that, to combat years of cultural conditioning, you approach each new opportunity by asking these five questions (my comments in italics):

(1) Does this opportunity fit my [professional] agenda and identity? (That is, does it contribute to a conscious career strategy, or is it just another shiny bauble for the CV?)

(2) Will this bring me joy’? (Are the reinforcers intrinsic or social/artificial?)

(3) Do I have time to do a good job without sacrificing existing commitments? (Every task incurs opportunity costs. What will this one cost you?)

(4) Does the opportunity leave space for my personal life? (More opportunity cost.)

(5) Am I uniquely qualified to fill this need, or could someone else do it just as well? (One decent time to consider “taking one for the team” is when only you have the needed skill set. But don’t flatter yourself — how often is that really the case?)

Finally, with a nod to the seductive lure of the GOODBAD, I’ll add one more key question, just to be safe:

(6) Who benefits most from this effort?

This is merely the big picture implied by previous items. Of course you care about the “good of our discipline,” but just because you’re exhorted to commit to something on this basis doesn’t mean that doing so is a good idea for you. So try saying YES to NO once in a while. You might just end up happier.

For a followup to this post, see More on the Power of Should (Olympic Edition)

AUTHOR NOTE: Have a story about succumbing to the GOODBAD and regretting it? I’d like to hear from you, and if enough people share their stories maybe I’ll do a followup post. Or, perhaps you disagree with my perspective — for instance, there’s a whole Tragedy of the Commons slant on this that bears examining — and you feel compelled to rebut. If so, contact me about potentially writing an “In Response” post. Either way, I’m at tscritc@ilstu.edu.

Postscript 1: On How to Say NO

If you’ve resolved to try saying NO more often, you may be able to extract some helpful tips on this elusive art from an essay on “How to respectfully decline an invitation to a social obligation you simply do not feel like attending.” Other advice: here and here.

Postscript 2: The Cultural Anthropology of the GOODBAD

In his classic book Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches, Cultural Anthropologist Marvin Harris took a functional perspective on cultural practices. Across time and generations, these practices “evolve” (get selected) because groups that engage in them prosper. But that doesn’t necessarily make these practices easy for or attractive to individuals. What may “evolve” in parallel is a cultural explanation for the practice that manipulates motivating operations. To borrow one of Harris’ examples, take the Hindu religion’s stance on cows, which are considered sacred manifestations of the goddess Gau Mata and thus to be protected. In places like rural India, Westerners are often amazed to see hungry-looking peasants with very edible cows wandering amongst them. How foolish, outsiders may say. If only they would eat the cows they wouldn’t be hungry!

But an economic analysis reveals that cows are much more useful as a source of sustainable resources (particularly protein-rich milk) than a one-time feast. In the long run you will starve if you eat your cow.

Harris postulates that the religious admonition against cow-eating arose as a hedge against short-term temptation (eat your cow and you’ll feel full, but you’ll also incur the wrath of the gods!). It doesn’t matter, in this account, whether the religious admonition is factually correct because, gods or no gods, it’s effective in promoting behavior that sustains the community.

I suspect it’s similar with the GOODBAD. The peasant who won’t eat his cow and the professional who “takes one for the team” both may struggle temporarily while doing “the right thing.” Most scientists and practitioners, presumably, don’t fear divine retribution for turning down an opportunity, but they have been told a Chicken-Little tale which holds that, if people like you and me don’t volunteer our time to worthy causes, the things we value professionally (like scientific journals in my example above) will collapse and everything will go to hell and it’ll be our fault and nobody will like us.

It doesn’t matter if this tale is factually correct, because it is effective in promoting behavior that sustains the community. Indeed, it’s so effective that few people bother to question its veracity. And yet the test is simple: Turn down “for the team” drudgeries to free up time for things about which you’re passionate. If the GOODBAD is correct, your career and your discipline will implode. But I’m betting that doesn’t happen. Where your career is concerned, the more productive you are with what you’re passionate about, the further you’ll go. And as for the discipline, well, most of those shiny opportunities dangled in front of you aren’t really make-or-break for behavior analysis (it’s been around for a long time and likely will outlast all of us). For the tasks that are truly invaluable, have a little faith in contingencies: Should free labor become scarce, someone’s going to find some other way to keep the lights on. But as long as you work for free, of course, they don’t need to.

Postscript 3: Generational Differences in Attitudes Towards Work

It’s possible that the views expressed in this post will already be transparent to younger readers, as the delusion of career-as-sacred-duty may particularly grip Baby Boomers like me. Results of a 2019 international survey and other observations suggest that members of subsequent generations [Gen X (born ~1965 to1980), Millennials (~1981 to 1996), and Gen Z (~1997 to 2010)] may be less susceptible to the ill effects of the GOODBAD. In various ways these generations are thought to place more emphasis on quality of life and work-life balance. Saying NO might not be as difficult for them.

This is, of course, a broad generalization that doesn’t hold in every case — for instance, there may be regional and cultural differences (e.g., Americans particularly dig the GOODBAD), and I suspect that “sacred duty” attitudes are more deeply engrained in academia and the helping professions than some other domains. Nevertheless, generational shifts are worth noting. It certainly has been interesting to watch members of my generation become exasperated at younger colleagues who are unwilling to throw themselves under the metaphorical bus for a “good cause.” Boomers call them lazy and unconscientious, but perhaps they’re just being rational.

Postscript 4: We’re All Just Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders

If you’d like a different slant on some of the behavioral variables we’re talking about here, read an interesting discussion on what it’s like to be a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader. which apparently is way less fun than it may sound. From the article:

Making someone believe that belonging to something is so crucial to their existence that they should give up things that make them happy is exactly the kind of quality that the most effective cult leaders possess.