“(…) instrumentation is a form of time travel that transports characteristics that are distinctive of the era of its original making, design and use, into the present.”

Cavvichi & Heering, 2022

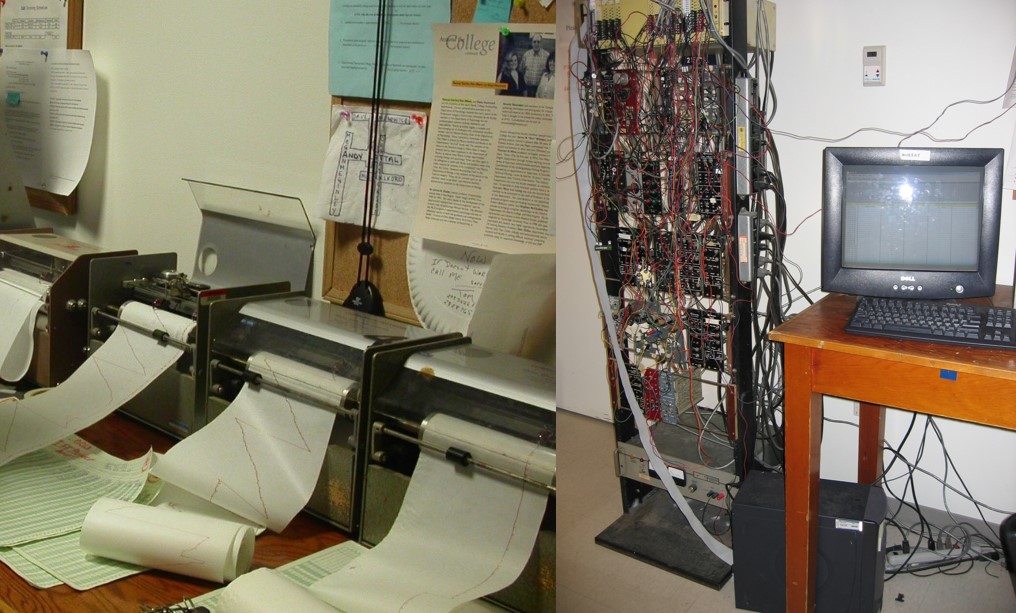

Working in a laboratory as a graduate student, to me, felt like being in a museum of scientific instruments of behavior analysis. Initially, the instruments that were most evident to me were the cumulative recorders (see Photo 1, below) and their corresponding operant chambers. As time passed, I learned more about scientific instruments in behavior analysis, their purpose and history. My advisor, K. A. Lattal is also a curator and collector of scientific instruments and a scholar in the history of behavior analysis.

Preserving the “old” and combining it with the “new” technology can still be seen in some operant laboratories like the one mentioned above. Escobar and Lattal (2014) described how, as shown in Photo 2 below, control panels on relay racks (including snap leads) are interfaced to computers. As Escobar and Lattal called it, this “curious marriage of old and new technologies” (p. 105), taught me to: be present in the laboratory and about the history of behavior analysis.

The sensory experience of listening to the sound of the cumulative recorders and seeing the records traced in red ink in the Lattal lab, was part of the learning process. What meant if there was a pause in the sound of a cumulative recorder? When would the red ink had to be refilled? These were possibilities and instances that required moment-by-moment interactions with the instruments that were allowing us to measure, analyze, and change behavior. Thus, interacting with instruments in the laboratory is essential to learning about behavior principles and their applications. Learning more about the functions (and dysfunctions) of these scientific instruments also entailed learning about the history of the experimental analysis of behavior.

Photo 1. Left. Cumulative recorders and Photo 2. Right. Relay rack with control panels for operant chambers interfaced to a computer. Both photos are from K. A. Lattal laboratory in West Virginia University, taken by Mirari Elcoro.

What is a Scientific Instrument?

Curators Deborah Jean Warner, of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC (Warner, 1990) and Liba Taub, from the Whipple Museum of the History of Science in Cambridge, UK (Taub, 2019) addressed that question.

But before I dive into how curators and museums contribute to teaching and learning, let’s examine what Warner and Taub have to say about the definition of scientific instruments. It is important to emphasize that in this post, I am referring to scientific, laboratory instruments, particularly in behavior analysis.

Along with the term instrument, these curators noted that the words object, device, apparatus, and machine, may frequently be used as synonyms. They also examined how the definition of the term instrument has changed over the years in the Oxford English Dictionary (Taub, 2019). Warner and Taub noted that the function, manufacturer, and historical context of creation and use, are all part of the definition of a scientific instrument. Accordingly, the following quotes allow to draw connections between the work of curators of scientific instruments and teachers of behavior analysis:

“Historic scientific instruments provide a point of access for understanding the history of science.”

Holland, 2002

“ (…) in settings where historical instruments are introduced into classrooms, the historical context is suggested, and becomes a worthy basis for discussion.”

Cavicchi & Heering, 2022

The interactions between human users and scientific instruments are intimate, dynamic, and reciprocal. Taub (2019) reflected about the complexity of defining a scientific instrument by asking if living organisms could also be considered instruments, given that some are models to conduct research. Take for instance, in behavior analysis, the pigeon and the rat are models to examine behavior in the laboratory. Are pigeons as well as cumulative recorders, operant chambers, relay racks, and computers, also scientific instruments?

Similar to how Taub (2019) asked if living organisms are instruments, Lattal and Yoshioka (2017) proposed that humans are refinable scientific instruments. More specifically, humans learn to arrange contingencies of reinforcement and punishment and how to measure behavior as accurately as possible. Lattal and Yoshioka elaborated on the varied influential variables on the performance of a human as a scientific instrument (e.g., physiological, social, environmental, conceptual framework of the human instrument). Such variables and their interactions will in turn affect the relation with technology.

But let’s get back to how these scientific instruments can be used in teaching and learning behavior analysis. These intimate, dynamic, and reciprocal interactions between students, teachers, and instruments are powerful ways to demonstrate behavior principles, schedules of reinforcement, and behavior change. These interactions, especially in settings that contain the actual (not virtual) laboratories with the “old” and the “new” set the occasion to teach and learn about the history of behavior analysis.

Lattal (2004) wrote extensively about the cumulative recorder in his article titled “Steps and Pips in the History of the Cumulative Recorder” (see other of his publications on cumulative recorders such as Lattal, 2021). The history of the cumulative recorder entails the history of the experimental analysis of behavior, with its technological roots being in the kymograph, a scientific instrument used to record physiological variables (e.g., blood pressure) over time (Lattal, 2004). Lattal described how Skinner’s interest in “moment-to-moment changes in behavior in real time as a function of environmental changes” drove him to adapt to kymograph to measure behavior, and design and create the cumulative recorder (Lattal, 2004, p. 331).

Being Part of a Laboratory

Thinking about us humans as scientific instruments can makes us fit right in to a laboratory; only if we actually work in one. Along with highlighting influential readings, Melissa Swisher (2024), Lecturer in the Department of Psychological Sciences at Purdue University, explained in her latest blog Impactful Reading for New Behavior Analysts, that being part of a laboratory is essential in learning behavior analysis. As Swisher shared, as a member of a laboratory, you learn the lore, create your own stories of learn the science of behavior, and learn how to analyze and change behavior.

Swisher’s experiences reminded me of a wonderful memoir titled Lab Girl about being a woman in a scientific laboratory by Hope Jahren (2016). Although Jahren’s experience is in botany, not behavior analysis, much of her learning experiences included in the book, with the added bonus of content of being a woman in science, are germane to the importance of interacting with instruments and the setting of teaching of learning that the laboratory affords in in many disciplines.

But creating and maintaining a laboratory may not be possible in certain educational settings. A laboratory is costly, especially if caring for animals. So, if you are a teacher of behavior analysis and have no laboratory, what are some options out there to approximate these influential experiences into your teaching?

Virtual Reality, Classroom Demonstrations,and Software to Simulate a Laboratory Experience

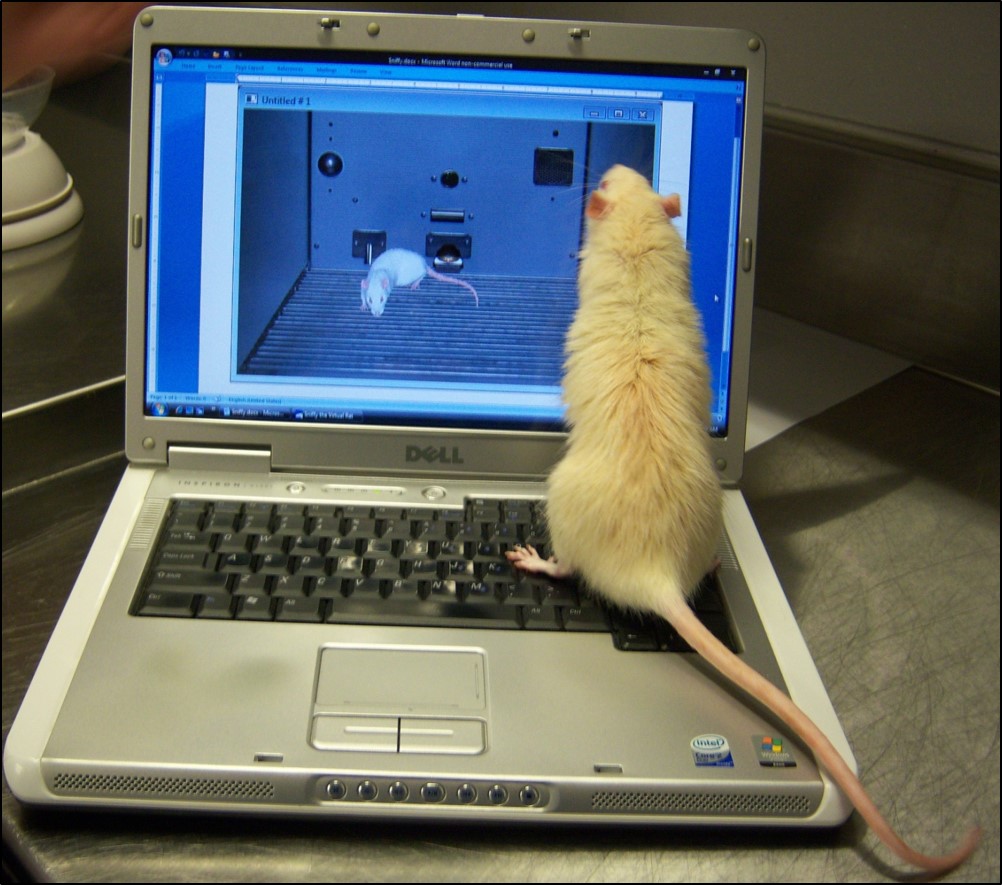

As suggested by the length of the title of this subsection, there are, fortunately, many alternatives out there and our experienced and caring teachers of behavior analysis have tried them. Swisher (2023), described some of these options on her blog titled Teaching Operant Conditioning Principles via Virtual Reality and In-Class Demonstrations. In this blog, Swisher describes the shaping game, the Portable Operant Research and Teaching Lab (PORTL, see Hunter & Rosales-Ruiz, 2023), Sniffy the Rat, and others.

Elcoro and Trundle (2013) compared the experiences of students using a real rat in an operant conditioning laboratory versus a virtual rat. In general, students learned in both environments, but preferred the experience in the actual laboratory with the real rat. Although these results are compelling and support the maintenance and funding of operant animal laboratories in academia (e.g., Bulla & Woodcock, 2024), there are still teachers of behavior analysis who may not have access to a laboratory. In these cases, it is worth implementing the options presented above.

Photo 3. Real rat and virtual rat on laptop. Taken by Melissa Trundle at Armstrong State University.

Museums and Teaching Behavior Analysis and its History

Besides the laboratory, a setting that provides myriad opportunities for teaching and learning is a museum of scientific instruments. I started this blog sharing how the Lattal lab at West Virginia University was like a museum. I also mentioned how my advisor, K. A Lattal, is a collector and curator of scientific instruments in behavior analysis. Well, you will see where I’m going with all of this. Consider that all these experiences are part of my learning history.

Carrying this behavioral history to my first academic job after gradaute school, I was lucky to arrive into a a laboratory setting with “old” and “new” instruments. I recognized some, but not all of the scientific instruments. To find out and use scientific instruments to teach about learning and behavior and history of psychology, Elcoro and McCarley (2015) used a surplus of “older” instruments to teach students about the history of psychology and measurement of behavior. Part of the assignments entailed creating a label to incorporate key aspects of the instrument, as if shown in a museum. Students in Learning and Behavior and History and Systems courses collaborated in this project and eventually organized a museum display that incorporated their work for their courses.

As you can gather, my behavioral history served as inspiration to collaborate in the project described above. I also happened to be at a place where these “older” instruments were available. But again, what if this is not available? Well, I invite you to visit the Behavioral Apparatus Virtual Museum, part of the Aubrey Daniels Institute. With some of the resources shared thus far, consider incorporating this virtual museum into your teaching of behavior analysis. This virtual museum includes photographs and descriptions organized in five virtual rooms, each dedicated to: Environments (Room 1), Observation and Measurement (Room 2), Presenting Stimuli (Room 3), Arranging Consequences (Room 4), and Responses (Room 5). It is worth noting that:

“The museum is indebted to the Association for Psychological Science (formerly the American Physiological Society) for providing its curator, Andy Lattal, with a summer teaching grant that made possible much of the preliminary work culminating in this display, and to Warren Street, who was instrumental in providing photographs of many of the items.”

https://www.aubreydaniels.com/about/aubrey-daniels-institute/behavioral-apparatus-museum

References

Bulla, A. J., & Woodcock, M. . (2024). Ratsketball: Using low-cost 3D printed operant chambers to probe for generative learning. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis, 50(1), 67-84. https://doi.org/10.5514/rmac.v50.i1.88703

Cavicchi, E., and Heering, P. (2022). Introduction: using historical scientific instruments in contemporary education – experiences and perspectives. In E. Cavicchi and P. Heering (Eds.) Historical Scientific Instruments in Contemporary Education (pp. 1-13). Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/61195

Elcoro, M., & Trundle, M. B. (2013). Student preferences for live versus virtual rats in a learning course. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7 (1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2013.070116

Elcoro, M., & McCarley, N. (2015). This Old Thing? Using old laboratory equipment to enhance student learning. Teaching of Psychology, 42(1), 69-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628314562681

Escobar, R., & Lattal, K. A. (2014). Nu-way snaps and snap Leads: an important connection in the history of behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst, 37(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-014-0008-z

Holland, J. (2002). Historic scientific instruments and the teaching of science: a guide to resources. In M. R. Matthews (Ed.), History, Philosophy & New South Wales Science Teaching Second Annual Conference (Sydney: 1999) (pp. 121-29). Retrieved from: https://www.brianjford.com/AvL11.htm

Hunter, M.E., & Rosales-Ruiz, J. (2023). The PORTL Laboratory. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 46(2), 355–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-023-00369-y

Jahren. H. (2016). Lab girl. Penguin Random House.

Lattal, K. A. (2004). Steps and pips in the history of the cumulative recorder. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 82(3), 329–355. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2004.82-329

Lattal K. A. (2021). C-3s and model Ts: the machines behind two lovely farewells. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 44(2-3), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-021-00300-3

Lattal, K. A., & Yoshioka, M. (2017). Introduction. Instrumentation in behavior analysis. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis, 43(2). https://doi.org/10.5514/rmac.v43.i2.62309

Swisher, M. (2023, May 31). Teaching Operant Conditioning Principles via Virtual Reality and In-Class Demonstrations. Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) Blogs. https://science.abainternational.org/2023/05/31/teaching-operant-conditioning-principles-via-virtual-reality-and-in-class-demonstrations/

Swisher, M. (2024, April 3). Impactful Reading for New Behavior Analysts. Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) Blogs. https://science.abainternational.org/2024/04/03/impactful-reading-for-new-behavior-analysts/

Taub, L. (2019). What is a scientific instrument, now? Journal of the History of Collections, 31(3), 453–467. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhy045

Warner, D. J. (1990). What is a scientific instrument, when did it become one, and why? The British Journal for the History of Science, 23(1), 83–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4026803