Please note that this blog is co-written by members of the ABAI Practice Board. ABAI Practice Board website.

Introduction to the ABAI Practice Community Blog and Practice Board member co-author bios.

*This month’s blog was guest-written by Sarah C. Mead Jasperse, PhD, BCBA-D, Emirates College for Advanced Education and

Vanessa Minervini, PhD, Creighton University

We are writing this blog primarily for an audience of practicing behavior analysts. A parallel blog could be written for experimental behavior analysts and the benefits of having a “clinical colleague.”

Are you looking for someone who complements you perfectly? Are you searching for someone who answers the questions you ask and asks questions you can answer? Do you want to be around someone who makes you the best version of yourself? If you’re an applied behavior analyst and the science of behavior is your love language, then you might be looking for your “basic bestie”!

What is a basic bestie?

Before we explain what a basic bestie is and why you need one, we probably should introduce ourselves. We are Sarah and Vanessa, and we met as graduate students at the University of Florida in 2011. (Go Gators!) Sarah is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst – Doctoral ® and an Assistant Professor at Emirates College for Advanced Education in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Her research focuses on the implementation of applied behavior analysis (ABA) services in clinical and educational contexts. Vanessa is an Assistant Professor at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska, USA, and her research expertise is in preclinical behavioral pharmacology.

Sarah (L) and Vanessa at the Mid-American

Association for Behavior Analysis conference

in Omaha, Nebraska in 2019.

We might sound like an improbable match. After all, we don’t even work with the same species (shoutout to Vanessa’s beloved pigeons, rats, mice, and monkeys). While Sarah is making token boards, Vanessa is programming the infusion rate for the syringe pump attached to the operant chamber. When Sarah is writing goals and meeting with support teams, Vanessa is figuring out who will be feeding the lab animals this weekend. As Sarah graphs functional analysis data, Vanessa analyzes dose-response curves.

However, after some friendly banter about whose work has better perks, we realized we had several compatibilities. Perhaps most important, we both held a behavior analytic view of the world. We also realized that each other’s expertise was exactly what we needed to bring our own work to the next level. As an applied behavior analyst, Sarah benefited from understanding things like how medications affect behavior. As a behavioral pharmacologist, Vanessa found it advantageous to understand the challenges encountered in clinical work. Of course, we also figured out that we both love staying up way too late and laughing way too loudly while doing things that amuse mainly just us, like dressing up as a pigeon and operant chamber for Halloween. Thus, the “basic bestie” relationship was born. Vanessa became the basic bestie and Sarah the clinical colleague. Thirteen years later and oceans apart, the basic bestie relationship is stronger than ever, and we’re here today to encourage other applied behavior analysts to find their very own basic bestie!

Vanessa as a pigeon and Sarah as an operant

chamber at a Halloween party in grad school.

What is basic research and why does it matter for clinical ABA practice?

Basic research is focused on answering fundamental questions about how things work. This type of research often involves animal models of behavior but can also include laboratory studies with human participants, too. As stated by Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968, p. 91), “Non-applied research is likely to look at any behavior, and at any variable which may conceivably relate to it.” For example, basic research in behavioral pharmacology might investigate how exposure to differential nutrition (e.g., high fat) changes the effects of a drug (Serafine et al, 2023) or how the size of reinforcers affects choice between drug and non-drug alternatives (Minervini et al., 2019).

There are many reasons why people who deliver ABA services should be well-versed in basic research. Here are a few that come to mind for us. Additional reasons likely will come to readers’ minds.

Ethics: If a clinician is credentialed by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board ® at the BCBA-D, BCBA, or BCaBA level, then they are expected to adhere to the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2020). Section 2 – Responsibility in Practice begins with Subsection 2.01 – Providing Effective Treatment. In that subsection, the Code directs behavior analysts to “provide services that are conceptually consistent with behavioral principles, based on scientific evidence,” (p. 10). Basic research is the foundation upon which all of our interventions are built, and much of the scientific evidence for the principles underlying our services comes out of basic laboratories. Having a handle on the basic literature is one way that practitioners can ensure that the services they are delivering are conceptually systematic.

Knowledge and Skills: The job of an applied behavior analyst requires a specific set of well-developed knowledge and skills. For BCBAs, these professional requirements are laid out in the current version of the BCBA Task List/Test Content Outline (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2022). Basic research, or the experimental analysis of behavior (EAB), is mentioned in the very first section of the task list (A. Philosophical Underpinnings, A-4). In other sections, skills that have their roots in basic research (e.g., measure occurrence, identify the defining features of single-subject experimental designs) play a prominent role. Understanding the basic research from which these skills are derived helps practitioners take their knowledge and skills to the next level.

Practical Outcomes: If the purpose of applied work is to arrange the environment to increase or decrease socially significant behavior, then having a working knowledge of how various intervention parameters may affect behavior is incredibly useful. The contributions of basic research for this purpose should not be overlooked. For example, if a client stops responding as a behavior analyst thins a schedule of reinforcement, then the behavior analyst may want to consider potential schedule effects on behavior. Certainly, there are plentiful examples of schedule thinning and ratio strain in the applied behavior analytic literature. Yet, venturing beyond research papers in our tried-and-true journals can be a lot more fun when reading articles with a basic bestie. This also goes for the basic bestie, who now partakes in the excitement about applied research.

Clearly there are many benefits related to understanding basic research. Some practitioners are highly competent in these areas while others might be ready to embark on a journey through the basic literature but not know where to start because they might feel uncomfortable or not quite fluent with the material. This is where a basic bestie comes in! While Sarah has rudimentary experience with basic research, she can’t rattle off her top 5 EAB role models like she could with ABA mentors. She can’t read a cumulative record as fast as she can interpret a functional analysis graph. And she certainly can’t source basic literature to answer clinical questions in a timeframe that will make funders and concerned parties happy. So, in these cases, she uses the phone-a-basic bestie option.

How can a basic bestie help?

Sarah doesn’t need an excuse to give Vanessa a call, but she’s always happy to ring her basic bestie whenever she encounters an applied question that might find its answer in basic research. One powerful example of the impact that basic research can have on applied work occurred when Sarah was working in a residential program for adults who engaged in severe dangerous behavior.

(NOTE: Cue the Law & Order SVU disclaimer. “The following story is fictional and does not depict any actual person or events.” While based on a basic bestie experience, details in this example have been changed substantially and all identifying information has been removed. However, the medication and target behavior mentioned are part of a true story).

Sarah was working with a 24-year-old woman who was engaging in very dangerous head-banging. The requisite medical workup to rule out pain and other potential determinants of head-banging had been conducted. Physicians had prescribed a psychotropic drug named “Seroquel” to be given as needed. After receiving the medical orders, residential staff administered the drug whenever the client started hitting her head. Sarah noticed that the woman’s headbanging was continuing and possibly even increasing. She started to wonder if the woman had learned that head-banging resulted in access to the medication. In other words, was access to Seroquel reinforcing head-banging? So, she dialed up her basic bestie and asked, “Under what conditions will organisms self-administer Seroquel?”

Vanessa, being the behavioral pharmacology nerd that she is, was more than happy to dive into the published literature and come up with some answers. In this case, the answers came in an article published in Biomolecules & Therapeutics – a journal that Sarah can confidently say she never would have considered searching! In 2013, Cha et al. found that rodents would press levers reliably more frequently when the consequence was an intravenous infusion of quetiapine as compared to an intravenous infusion of saline. (FYI, quetiapine is the generic version of Seroquel. It’s also helpful to have a basic bestie who knows what drug name to search! Sarah would have been stuck looking for studies about Seroquel, but apparently no one is out there buying brand-name pharmaceuticals for their rodent friends if they can help it.)

So, rodents will self-administer quetiapine and will do so at levels that are higher than in a control condition. It maintained lever pressing and thus functioned as a reinforcer. The take-away message from the basic bestie was that applied behavior analysts should proceed with caution in the scenario Sarah encountered. While the abuse liability of Seroquel is nowhere near as high as, say, fentanyl, the possibility that Seroquel could become a reinforcer for a problematic behavior does exist. In this case, Sarah met with the prescribing physician and shared her concerns, which resulted in the “as needed” prescription being revised.

A basic bestie saves the day once again!

The basic bestie with her trusted sidekick.

Other questions that Sarah has asked Vanessa over the years include things such as:

Are there other ways I could program this intermittent reinforcement schedule?

How do I backtrack after hitting ratio strain?

Are there other ways I could fade demands in and reinforcement out?

How can I decrease this behavior without extinction?

How should I handle these competing schedules of reinforcement?

How could I use percentile schedules for shaping this behavior?

Is there new technology for how I can graph these data?

Even though many of these questions probably could be answered by Sarah staying in her own lane, a swerve over to the basic research always has resulted in her looking at the question a bit differently and evaluating options she hasn’t previously considered. Similarly, Vanessa gets a new perspective on basic research and its impact on providers, which then leads her to develop new ways to disseminate her research or communicate its clinical implications.

How can practicing applied behavior analysts engage more with basic research and find their own basic bestie?

If you’ve read this far and have decided that you want to engage more with basic research or maybe even want to find your own basic bestie, we have a few practical tips for getting started.

1. Read basic research.

This sounds simple, but figuring out how to start can be difficult. We recommend starting with a topic that interests you. For example, if the clinical concern of impulsivity is something you’re curious about, then you might want to start by reading something from the literature on choice. Next, dive in, but don’t worry about not understanding all of the procedures or statistics. (Basic bestie secret here…not even Vanessa understands all the statistics!) Focus on the big picture. Read the abstract. Scan the graphs. Skim the discussion. What is the takeaway point? How could that takeaway point be useful in clinical practice? Once you’ve cracked open a few basic research articles, you’ll start to see patterns and understand more about the procedures just as you did with ABA articles.

Ready to start? If you are credentialed through the Behavior Analyst Certification Board, head on over to your BACB Portal and enjoy your free access to a classic basic bestie journal – Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. You also can find plenty of EAB studies in two of ABAI’s journals – The Psychological Record and Perspectives on Behavior Science.

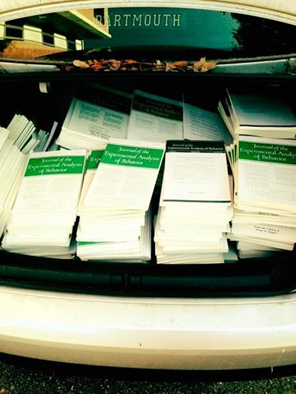

Sarah’s car filled with JEABs

as she prepared to move across

the country from her basic bestie.

If you’d like to start with something recommended by a basic bestie, check out any of these articles. Handpicked, with love, by Vanessa.

Odum, A. L. (2011). Delay discounting: I’m a k, you’re a k. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 96(3), 427-439. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423

Poling, A., Nickel, M., & Alling, K. (1990). Free birds aren’t fat: Weight gain in captured wild pigeons maintained under laboratory conditions. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 53(3), 423-424. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1990.53-423

Sargisson, R. J., & White, K. G. (2001). Generalization of delayed matching to sample following training at different delays. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 75(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2001.75-1

2. Attend basic research talks.

There are at least two ways to do this at conferences. First, you can intersperse basic and applied presentations. At a single-track conference, the conference organizers might make speaker selections to showcase both basic and applied work. Try to choose conferences that do this. At a multi-track conference, such as the Annual Convention of ABAI, you can arrange your agenda so you weave some basic research presentations into your schedule. The Society for the Quantitative Analysis of Behavior arranges tutorials at ABAI’s Annual Convention, with the goal to promote translational research and dialogue between basic and applied researchers. A second approach, and our personal favorite way to attend basic talks, is to frequent symposia that address a single topic from basic, translational, and applied perspectives with a discussant who can bring it all together. Again, choose topics that interest you and go into the presentation allowing yourself grace if you do not understand every detail.

(A quick hat tip here to Symposium #252 at ABAI’s Annual Convention in 2014, “Adjustment to Change” with Drs. Stephanie Kincaid, Cara Phillips, Andy Lattal, and Aubrey Daniels. An exquisite example of how we are one science, one field, and the turning point in Sarah’s understanding of what it means to be a behavior analyst and not just an applied behavior analyst.)

Sarah’s cherished Volumes of JABA and JEAB

positioned next to a piece of quintessential basic

research equipment – the Gerbrands cumulative recorder –

from her basic bestie’s lab.

If you’re planning to attend ABAI’s Annual Convention in 2024, you might consider checking out some of these basic research sessions.

Symposium #51: Basic and Translational Research of Variables That Contribute to Resurgence

Invited Symposium #99A: Rate Dependency: Still Useful After All These Years

Invited Tutorial # 114: SQAB Tutorial: Choice, Time, and Evolution: Dynamics in Self-Injurious Behavior

Symposium #313: Recent Evaluations of Choice Procedures Involving Reinforcing and Aversive Consequences

3. Network with basic researchers.

In our experience, contacting basic research is easier and more enjoyable when it is interactive, humanized, and done over cups of tea and with lots of laughs. So, of course, we encourage applied behavior analysts to network with basic researchers and find their own basic besties. To get started, attend basic research talks as discussed above and chat with the presenters after their sessions. Ask about the applied implications of their research. Like any of us, basic researchers love talking about what they do, so make their day with a question! Who knows, maybe that will be the start of a symbiotic basic bestie relationship! You also can join special interest groups (SIGs) about basic research. For example, ABAI has an Experimental Analysis of Human Behavior SIG. Go ahead and join! There also are plenty of interesting basic and translational researchers on social media who share their work freely and interact with followers.

Want to hear more about basic besties?

We’d like to thank Dr. Jennifer McComas and members of the ABAI Practice Board for the invitation to join as guest bloggers. We are passionate about the intersection of basic and applied work in the field of behavior analysis, and we jump at any chance to share our experience with others. We hope you’ve enjoyed hearing about our basic bestie journey! Please feel free to be in touch at Sarah.Mead@ecae.ac.ae or VanessaMinervini@creighton.edu.

References

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 91-97. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022). BCBA task list (6th ed.). Littleton, CO: Author.

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-code-for-behavior-analysts/

Cha, H. J., Lee, H. A., Ahn, J. I., Jeon, S. H., Kim, E. J., & Jeong, H. S. (2013). Dependence potential of quetiapine: Behavioral pharmacology in rodents. Biomolecules & Therapeutics, 21(4), 307-312. https://doi.org/10.4062/biomolther.2013.035

Minervini, V., Osteicoechea, D. C., Casalez, A., & France, C. P. (2019). Punishment and reinforcement by opioid receptor agonists in a choice procedure in rats. Behavioral Pharmacology, 30(4), 335-342. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0000000000000436

Odum, A. L. (2011). Delay discounting: I’m a k, you’re a k. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 96(3), 427-439. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423

Poling, A., Nickel, M., & Alling, K. (1990). Free birds aren’t fat: Weight gain in captured wild pigeons maintained under laboratory conditions. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 53(3), 423-424. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1990.53-423

Sargisson, R. J., & White, K. G. (2001). Generalization of delayed matching to sample following training at different delays. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 75(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2001.75-1

Serafine, K. M., Elsey, M. K., Beltran, N. M., & Minervini, V. (2023). Eating a high fat/high carbohydrate or ketogenic diet does not impact sensitivity to morphine-induced antinociception in rats with hindpaw inflammation. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 385(S3). https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.122.564700