On Sunday, February 11, 2024, the National Football League hosts its championship game (and the world’s foremost celebration of traumatic brain Injury), the Super Bowl, which will captivate between 100 and 200 million television viewers from all over the world, as long as by “the world” you mean mostly the United States.

Those viewers, by the way, comprise up to about 60% of the total U.S. population (maybe 80% if you subtract those without the capacity to care, such as infants, dementia patients, the criminally insane, and people lacking access to broadcast TV).

As Salon magazine put it:

The holiest of high holidays in all of American sportsballs never starves for attention. Regardless of who’s playing, it is always the highest-rated TV show of any given year.

Watching the Super Bowl on TV represents a clear case of reinforcer substitutes, given that the cheapest in-person ticket costs over $8000, and there are only about 72,000 seats available at any price. So many people will tune in to the Super Bowl that a 30-second television advertisement will sell for about $7 million dollars. It’s worth noting, by the way, that pioneering behaviorist John B. Watson is credited with helping to invent the modern approach to advertising. If you tune in to the game, bow to the great man while watching the E-Trade Babies duel it out on a pickleball court.

Anyway, many people care about the Super Bowl — according to a recent poll, in fact, more than care about Valentine’s Day. And no wonder, since the snacks are better: Those watching the Super Bowl at home will spend over $17 billion on special food and beverages for the occasion. For Valentine’s Day, the main expense is roses, and who eats roses?

So many people care about the Super Bowl that if you’re not one of them you can feel pretty isolated during this maelstrom of cultural obsession. I’m going out on a limb here, but I’ll speculate that the socialization that turns football viewing into a reinforcer has escaped a lot of Americans with advanced degrees. And I know for a fact that most of you who are not Americans are befuddled by football’s arcane rules and rituals, unless you’re Canadian, in which case you have your own version of the game, which is cute.

As a public service to my behavior analysis colleagues who feel bypassed by Super Bowl Fever, I offer the following list of diversions, guaranteed collectively to fill the long hours during which so many others are planted in front of their TVs.

You’re welcome.

And if these don’t work for you, there’s always Puppy Bowl XX.

1. Behavior Theory and Philosophy: Contemplate the Existential Status of the Game

You don’t have to watch football to engage with it. Instead, look into the rules and rituals of the game and conduct a conceptual analysis! I think that, among other things, you will find the game in desperate need of some help with behavioral pinpointing, For instance, take the game’s name, football, which seems woefully off base for a sport in which ball and foot make contact on just a few rare occasions. In reality, almost all football plays involve one player throwing the ball to another or one player running while holding the ball.

Why foot would be emphasized over hand, therefore, is a real verbal behavior mystery. And it should be noted that, in this excessively violent bro-fest of a sport, the only player who is truly responsible for foot work, a kicker, is regarded by teammates and fans as the least macho person on the field. Moreover, casual observation of the game will reveal that a football touches buttocks more often than it touches a foot (see adjacent image and here). Making sense of that should fill a couple of hours at least.

2. Literature Review: Behavior-Analytic Research About Football

Bogus statistics on male mathematical superiority notwithstanding, nothing strips the splendiferous gladiatorial muscularity from a sport like quantifying it (e.g., see “Are super-nerds really ruining U.S. sport?“). Dudes with advanced degrees should appreciate that statistics are a great leveler between Alpha and Beta (or even Gamma) males. Advanced analytics have assumed such a prominent place in sports recently that the boundary between athletes and mathletes has blurred — As Exhibit A, consider the Green Bay Packers fan who applied for a coaching job with the team on the strength of his experience with fantasy football.

Anyway, for those who prefer to approach football intellectually rather than physically, at the bottom of this post you’ll find a fairly extensive, though probably incomplete, bibliography of behavior analytic studies focusing on the sport. There are some really clever interventions to help people learn and play the game, but to me this sort of physiciality-by-proxy is not far enough removed from the sweat and blood and brain injury of actually playing the game. I’m therefore rather partial to the pure cerebral exercise of examining football outcomes through the lens of quantitative models. But each to his own.

As you fill a few hours digesting these studies, take arrogant nerdy pleasure in the fact that few if any of the overpaid jocks suiting up for this year’s game are capable of reading them. Or even just reading.

3. Literature Review: Research on Competing Reinforcers

Not everyone loves sports, but among those who do I predict a modest negative correlation between level of interest in American football and interest in other games involving feet and balls. Not a football person? No worries; I’ve gotcha covered. At the bottom of this post, you’ll find a bibliography of studies on futbol, a game actually played using the feet that Americans charmingly refer to as soccer, a name which makes sense only if you imagine derivation from socks to form a metonymical tact, albeit one that’s about as sane as calling broccoli a refrigerator (yes, please vote for me for Obscure Verbal Behavior Joke of the Week).

For the sake of thoroughness, I’ve also included a few studies on Australian Rules Football and rugby. In the latter case, as a former club hooker (filthy minded Americans, see here to purge your thoughts from the gutter), I can attest that rugby is far more of a foot game than the ineptly-titled American sport. [Moreover, rugby puts the macho bluster of football into a whole new perspective. Ruggers manage to achieve athletic excellence while simultaneously consuming more alcohol than your typical American football tailgater, whose sole form of exertion is struggling to his feet to watch the halftime show. For insight into the relationship between alcohol and rugby, see here and here. Oh, and by the way, unlike the macho posers who play American football in shoulder pads and thigh pads and shin pads and elbow pads and neck rolls and rib pads and rigid polycarbonate helmets and warm gloves for their delicate little fingers, ruggers wear no special protective gear during competition. They view American footballers the way American footballers view kickers.]

Finally, although it doesn’t involve a ball, or a foot, and there’s no behavior analytic research of which I’m aware, I couldn’t resist including a few papers about curling because, really, if you’re not into curling yet, what’s wrong with you?

4. Explore Complementary Reinforcers

I mentioned that Super Bowl fans will spend some $17 billion on food and drink for the game. This represents a significant uptick in snack purchasing over non-Super-Bowl baselines, illustrating how access to one reinforcer can magnify demand for another. Behavioral economists refer to this as complementary reinforcers, an effect that flies in the face of the more-common substitutability of qualitatively different reinforcers, for instance as per the matching law.

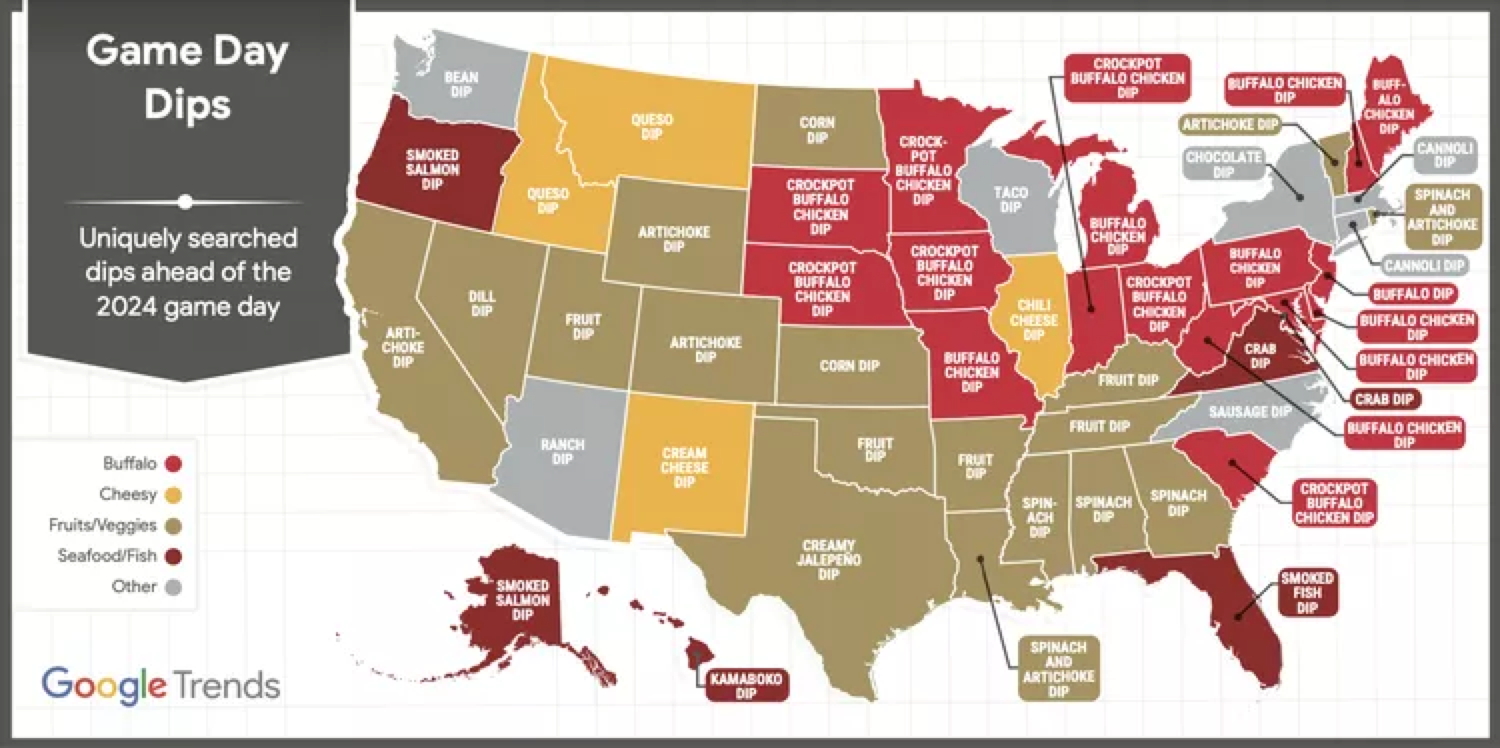

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, there are geographic differences in complementary reinforcers. Here, for instance, courtesy of Google Trends, is an accounting of favorite game-day party dips, by U.S. state. You can squander at least 45 minutes musing on why watching football facilitates different reinforcers in different states.

5. Conduct A Case Study in Incompatible Behaviors

It should come as no surprise to behavior analysts that watching football, like any high-probability behavior, can supplant other behaviors. During the game, viewing of tennis, golf, and other sports decreases precipitously (as a result, television networks tend to show relatively few other sporting events at this time). Attendance plummets at church services, community events, movie theaters, and some kinds of restaurants. And so on.

Some behaviors, however, fluctuate in frequency during the big game. The best-known example may be the tendency for millions of people to use the bathroom during the halftime break. Game-watching largely precludes this behavior (except in infants, dementia patients, the criminally insane, and people lacking access to broadcast TV). Motivating operations gradually build up until, when the game pauses, a literal flood of bathroom demand is unleashed.

As a fun way to fill some time during the game, try measuring people’s pit-stop frequency during game action versus breaks in play (e.g., commercials, halftime).

I love this research idea, perhaps in a modified multi-element design, and your work, if successful, may enshrine you in a surprisingly large, nay massive, behavior analytic literature on all things bathroom-y (for just a few of many possible examples, see here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here… Holy shit. Next time someone tells you that behavior analysis is headed into the toilet, tell them it’s already there).

So, good research topic! But to explore it you will have to surmount some major methodological hurdles. For example, you’re unlikely to be able to directly observe other people’s bathroom breaks, much less insert multiple observers into each vestibule to obtain interobserver agreement. This means relying on verbal self-reports of “bathrooming,” or perhaps on behavior products (like flushing noises or changes in local water pressure) rather than real behaviors. Overall, what you come up with might be interesting, but according to the venerated seven-dimension framework, I’m afraid, it won’t count as applied behavior analysis. Sorry.

However, if against all logic you decide to pursue this inquiry, consider, for extra excitement and communion with our field’s historical traditions, plotting the results as a cumulative record! Unfortunately, because individual fans are unlikely to use the bathroom repeatedly in a short time span, it won’t be possible to employ the rate-focused display of a Standard Celeration Chart. And even if that were possible nobody would be able to read your graph anyway.

6. Contemplate Taylor Swift

No consideration of Super Bowl 2024 would be complete without attending to Taylor Swift. I’m not talking about conspiracy theories speculating that Swift has rigged the game as part of a nefarious left-wing plot — although that is certainly an interesting window into certain kinds of disordered behavior.

No, let’s keep this simple and politically neutral. Swift, who will be at the game, is the only cultural phenomenon in America bigger than the Super Bowl. Far more behavior is focused on Swift than on football. This means that during the broadcast, the camera will pivot often to Swift because viewers demand it. And I suspect that vendors who ponied up $7 million for a commercial spot will be disappointed in the resulting contrast effect: Commercials don’t show Taylor, so why would anyone watch them?

Any behavioral happening this big demands the consideration of specialists in behavior like us. However, for those who are lukewarm to football, there’s a major practical challenge: You won’t be able to watch Swift without watching the stupid game. For some of you that might be a bridge too far, even for a glimpse of Taylor. Therefore, at the bottom of this post I’m offering you a brief, if gratuitous, substitute activity: As food for thought, a 300-word, AI-authored essay on the relationship between Taylor Swift and operant conditioning. I’m not saying it’s great, but reading it can fill a couple of minutes. If you really get desperate for something to do, you can always take on that conspiracy theory.

7. Go for a Walk

Finally, unless you are deceased, you have to emit some behavior, and walking has been unequivocally documented to be a behavior. To fill some time, walking is always a good choice for physical health reasons, and a growing body of research indicates that contact with nature contributes to good mental health. If you are able to venture into green spaces on your walk, you’ll be doing better than those $8000-per-ticket Super Bowl fans who merely shuffled across a parking lot to sit in a giant concrete bowl for four hours. And you’ll be WAY ahead of those stay-at-home fans who only walked to the bathroom at halftime.

If you do walk, just be careful when and where you do it. For several hours after the game, traffic fatalities spike about 40% over normal, a rate even higher than on New Year’s Eve [you didn’t think $17 billion was spent entirely on dip, did you?]. Long story short, you don’t want to be anywhere near the roads while drunken fans are driving home. I suggest getting your walk in early, leaving time later, while everyone else is crashing their cars, to check social media for pics of Taylor at the game.

Behavior Analysis Literature on American Football

-

Behavioral interventions to improve performance in collegiate football

- A behavioral approach to coaching football: Improving the play execution of the offensive backfield on a youth football team

- Behavioral coaching in the development of skills in football, gymnastics, and tennis

- Functional analysis and behavioral coaching intervention to improve tackling skills of a high school football athlete

- Behavioral coaching to improve offensive line pass‐blocking skills of high school football athletes

- A behavioral intervention for teaching tackling skills to high school football athletes

- The generalized matching law in elite sport competition: Football play calling as operant choice

- Effects of posting self-set goals on collegiate football players’ skill execution during practice and games

- The effects of verbal instruction and shaping to improve tackling by high school football players

- An observational study of a successful pop warner football coach

- A matching law analysis of risk tolerance and gain–loss framing in football play selection.

- The matching relation and situation‐specific bias modulation in professional football play selection

- Explanatory flexibility of the matching law: Situational bias interactions in football play selection

- Defensive performance as a modulator of biased play calling in collegiate American-rules football

- Application of the generalized matching law to point-after-touchdown conversions and kicker selection in college football

- Direct versus indirect competition in sports: A review of behavioral interventions.

- Decision-making on the hot seat and the short list: Evidence from college football fourth down decisions

- Scaling N from 1 to 1,000,000: Application of the Generalized Matching Law to Big Data Contexts

- Pain acceptance among retired National Football League athletes: implications for clinical intervention

Behavior Analysis Literature on Futbol

- The use of acceptance and commitment therapy for stress management interventions in football

- A brief educational intervention using acceptance and commitment therapy: Four injured athletes’ experiences

- The Comparison of Metacognitive Group Intervention and Group Acceptance-Based Behavioral Therapy on Competitive Aggression of Anxious Professional Soccer …

- Mindfulness and acceptance in sport: How to help athletes perform and thrive under pressure

-

Applied behavioural analysis in top-level football: Theory and application

- Acting on Injury: Increasing Psychological Flexibility and Adherance to Rehabilitation

- The comparison Effectiveness of the Third Wave Behavioral Therapies on Behavioral Inhibition/Activation Systems of Anxious Football Player

- The Flourishing Footballers programme: Using psycho-education to develop resilience through ACT

- Effects of mindfulness training and locus of control on self-efficacy of professional football players in Nigeria.

- Effects of public posting, goal setting, and oral feedback on the skills of female soccer players

- Training soccer goalkeeping skills: Is video modeling enough?

- Reducing risk of head injury in youth soccer: An extension of behavioral skills training for heading

- Peer behavioral coaching: Soccer

- Team sports for the severely retarded: Training a side‐of‐the‐foot soccer pass using a maximum‐to‐minimum prompt reduction strategy

- Using behavioral skills training with video feedback to prevent risk of injury in youth female soccer athletes

- Visual exploratory activity and resultant behavioural analysis of youth midfield soccer players

- Self-regulation of practice behavior among elite youth soccer players: an exploratory observation study

- Effects of goal setting, individual and group contingencies on learning and effort by talented youth soccer players

- Spectator verbal behavior in organized youth soccer: A descriptive analysis

BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS Literature on Other Games Involving FEET AND Balls

- Modeling the quality of player passing decisions in Australian Rules football relative to risk, reward, and commitment

- Effects of Behavioral Coaching on the Place-Kicking Skills of High School Rugby Players

- Positive Behavior Management: Assessment of Rugby Referees in Children Sport

Curling!

- An Analysis of Curling Strategy

- The sports science of curling: a practical review

- The motion of a curling rock

What Chat GPT Generated About Operant Conditioning and Taylor Swift

Taylor Swift, the iconic pop sensation, may seem worlds apart from the realm of operant conditioning research, a fundamental principle in psychology pioneered by B.F. Skinner. However, upon closer examination, intriguing parallels emerge between Swift’s career trajectory and the principles of operant conditioning.

Operant conditioning is a theory that suggests behavior is influenced by its consequences. Rewards and punishments shape behavior, leading to learning and behavioral change. In the case of Taylor Swift, her rise to stardom exemplifies the principles of operant conditioning. Swift’s early successes, such as winning awards and gaining recognition for her music, served as positive reinforcement, strengthening her musical talents and motivating her to continue pursuing her career in the music industry.

Moreover, Swift’s ability to adapt and evolve her image and musical style to suit changing trends reflects the concept of shaping within operant conditioning. Like a subject in an experiment, Swift learned to modify her behavior (i.e., her musical style) to elicit positive responses from her audience, thereby ensuring continued success and relevance in the ever-changing music industry.

Furthermore, the media’s response to Swift’s actions and behaviors provides a fascinating illustration of operant conditioning’s principles. Swift’s strategic use of social media and public appearances to garner attention and maintain her fan base can be likened to operant behaviors aimed at obtaining reinforcement in the form of publicity and adoration from her fans.

However, operant conditioning also highlights the potential pitfalls of fame and public scrutiny. Swift’s experiences with criticism, controversies, and negative publicity serve as examples of punishment within the framework of operant conditioning. Despite facing backlash and setbacks, Swift has demonstrated resilience and adaptability, learning from her experiences and using them to inform her future actions and decisions.

In conclusion, the relationship between Taylor Swift and operant conditioning research is a compelling one, highlighting the ways in which principles of behavioral psychology can be observed in the context of celebrity culture and the entertainment industry. Swift’s journey serves as a vivid illustration of how rewards, punishments, and reinforcement shape behavior and influence outcomes in both individuals and society at large.