Author note: I thank Shahla Alai-Rosales of University of North Texas, and Odessa Luna and Paolo Millán Santiago of St. Cloud State University, for invaluable assistance in helping me think through some of these issues. This post expresses my views and is not intended to represent theirs. If you want to be mad at somebody make it me.

Does Professionalization Promote Inequity?

You should check out an unsettling article by Dána-Ain Davis and Kelley Akhiemokhali, in Sapiens Magazine, on racial disparities in access to maternal health care in the United States. The raw statistics underpinning the article are unsurprising. Pretty much however you measure, people of color have less access to health care than whites. What’s disturbingly detailed in the article is how, in the area of maternal care, we arrived at such disparity.

A smear campaign. The story begins with the “professionalization” of the obstetrics and gynecology medical specialty area starting in the mid 1800s. Prior to that, most childbirth, for people of all racial groups, took place in the home under the supervision of (inexpensive) midwives, who were disproportionately women of color and members of other underrepresented groups. But then hospitals (often the fee-for-services kind) established maternity wards, and physicians (mostly white and male) began promoting formal credentialing as an essential of maternity care. Physicians also embarked on an aggressive public relations campaign with two foundations. First, they set out to persuade the public that medical technology (e.g., drugs, specialized instruments like forceps) was essential to safe births and could be employed only by a trained physician. Second, they depicted their competition — midwives, and particularly black midwives — as unskilled, unsanitary, and unsafe, claiming that that midwives were responsible for the high newborn mortality rate that existed at the time.

The campaign worked like a charm. Today, about 90% of American births are overseen by a physician rather than a midwife, the vast majority in hospitals rather than at home.

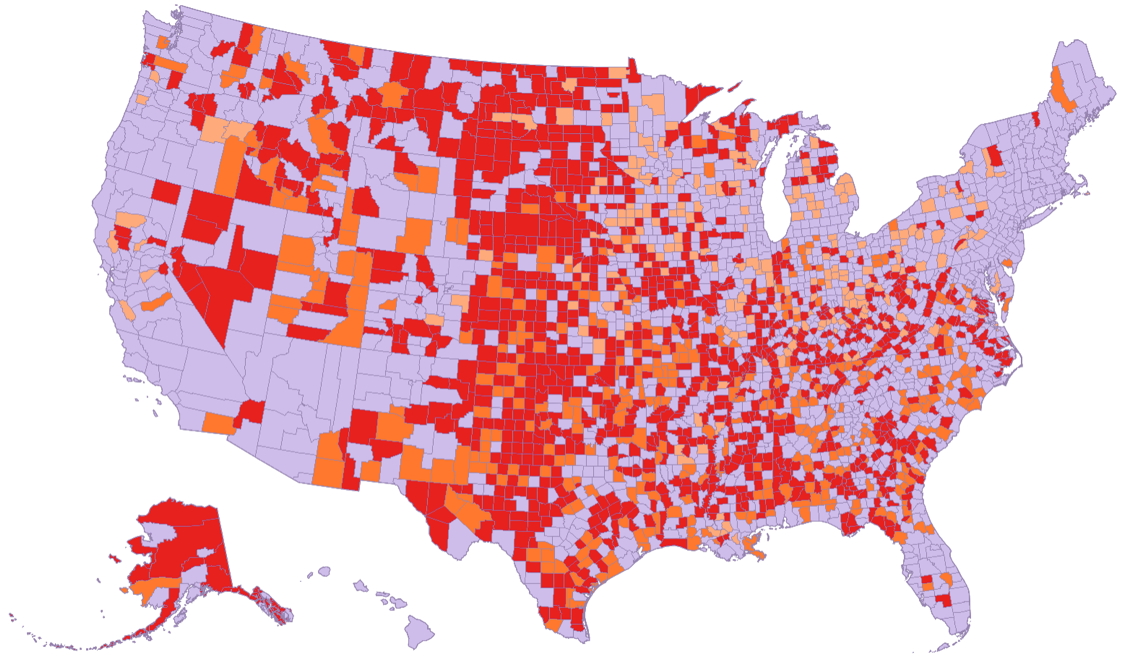

Supply and demand. Now, as I have discussed elsewhere, credentialing and other steps taken to create a “profession” always serve partly to regulate the supply of and demand for professionals. The fact that only certain people meet the requirements for joining the profession serves as both quality control and supply regulation. The former is said to serve the pubic, and the latter works to the economic advantage of the profession — that is, for individual members of a profession, the rewards are maximized when demand outstrips supply. From this functional perspective, it’s perhaps no surprise that today there’s not enough maternal care to go around. In the map, gray areas have adequate access to maternal care. Orange areas have limited access. Red areas are “maternity care deserts,” which the March of Dimes defines as “where there are no hospitals or birth centers offering obstetric care and no obstetric providers.” According to the March of Dimes, annually this shortage affects about half a million births.

Importantly, maternity deserts aren’t randomly distributed. Once maternal care became linked to a credentialed profession, specialized technology, and hospitalization, prevailing conditions assured that women of color would receive less care. One reason is the cost of physician services. Economic disparities in the U.S. tend to follow racial lines, with fewer people of color having the financial resources (today including health insurance) to pay for medical care. Another reason is the loss of alternatives. Because the demand for midwives cratered, fewer women, particularly women of color, became midwives over the years. There are now far fewer midwives than in the 19th Century, and about 90% of American midwives are white.

Today, with physicians mostly calling the shots, the difference in infant mortality between Blacks and whites is greater than it was in 1850, when mortality rate was used to justify the marginalization of midwives in the first place.

The owner-class hypothesis. As awful as this story is, it’s important to separate the physicians’ blatantly racist grab for market share from the race-specific effects that unfolded down the road. As my colleagues Odessa Luna and Paulo Millán Santiago of St. Cloud State University pointed out to me, there is a long history of “owning classes” (those possessing resources and influence) building an economic system that benefits them but creates unhappy side effects for others. Often in America the owning class is white and the “others” are not, but not always. For instance, in West Virginia, where I grew up, a white owning class (mine operators) built an economic system around coal extraction that made them wealthy but at great cost to mostly-white “others.” Wealthy industrialists absolutely intended to centralize their control of an industry that was once dominated by small operators. Once they controlled market share, long-lasting adverse effects (economic, health, and environmental) ensued for mine workers and local communities. The blinders of privilege, however, made it possible for them to overlook this.

Analogously, 19th Century physicians absolutely intended to prevent black midwives from practicing (and there is no question about the racist overtones of their grab for market share). Once the architects of the obstetrics and gynecology profession tipped the first domino, a whole sequence of additional dominos fell, one after the other, to create 150 years of poor maternity care for women of color. Depriving women of color of care may not have been the express intent, but the blinders of privilege made it possible for physicians to overlook this racist consequence of professionalizing maternal care.

Surely We’re Better (Right?)

This got me to thinking about a contemporary case in which a group of people with education and privilege succeeded in establishing a new system that benefitted them. I’m talking about the creation of applied behavior analysis as a profession in which the right to practice and ability to bill for services are reserved for people with a certain credential.

Let me be clear about a couple of things. First, I say the new system benefitted applied behavior analysts because it’s true. For a profession to exist, professionals have to get paid. Nothing insidious per se in that. Second, the people who started certification and worked tirelessly to get ABA covered under health insurance had the best of intentions. Some of them helped to create ABAI’s statement on the consumer’s right to effective treatment. Others emphasized the need for ethical guidance and practitioner quality control. When we speak of the engineers of today’s ABA profession, we’re not talking about evil people, and as a result of their efforts more people receive ABA services today than ever before.

But it’s equally true that the systems that support credentialing and third-party payment were the product of privilege. That is true by definition. The people who made this happen were well educated, in a country where only about 25% of adults possess a Bachelors degree (and those degrees are not distributed equally; the percentage of white people with college degrees is roughly double that of people of color). And in America, although education doesn’t guarantee riches, being white does correlate with a certain amount of generational wealth and influence. Unsurprisingly, the main movers and shakers of the ABA profession were well educated white people, as are the economic beneficiaries of their efforts (about 70% of BCBA and BCAB-D certificants are white and they are all, as required by the certification process, well educated).

Race and money and geography. Which brings us back to the “owner class” hypothesis, which posits adverse consequences of systems built by and for the privileged. Based on this hypothesis we can predict that the availability of services provided by Board Certified Behavior Analysts will be especially low:

- For members of underrepresented groups

- Where BCBA earning potential is low

Below, we’ll examine these predictions with the help of some amazing datasets created by University of Louisville’s Marissa Yingling and colleagues. I cannot recommend strongly enough that you check out her papers that are linked here. They should be required reading for anyone hoping to make a living in ABA.

Let’s start by acknowledging two things. First, providers of ABA services aren’t distributed equally across the U.S., and on a county-by-county basis the ratio of autism spectrum disorder cases to BCBAs can vary by a factor of 100. Figure 2 of a 2021 article by Yingling and colleagues shows the existence of “behavior care deserts” quite reminiscent of the maternity care deserts depicted above (sorry, I’d love to show you the figure but SpringerNature wanted to charge me a fat fee to reproduce it). Second, a system based on for-profit services necessarily maps on to pre-existing economic disparities to produce unequal access to care. In the U.S., economic disparity tends to follow racial lines, so we can predict that people without a lot of wealth — disproportionally non-whites — will be able to afford less care. It’s been reported that autism services in general are less available to people of color. Whether this may be true specifically for ABA services is a complicated subject, as I’ll explain in due course.

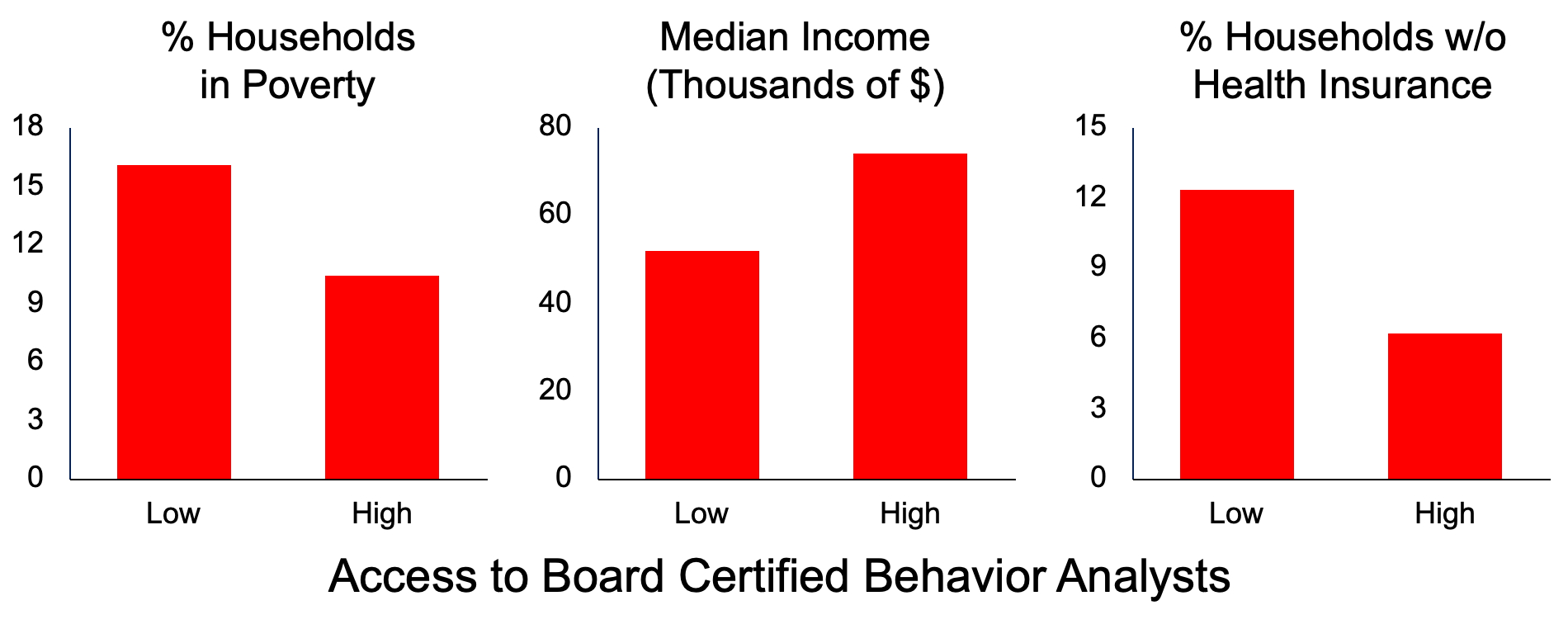

Yingling and colleagues have reported that U.S. counties with low availability of Board Certified Behavior Analysts have slightly higher proportions of black and Hispanic individuals. The difference isn’t statistically significant, but don’t jump to conclusions yet.

What more strongly correlates with the availability of BCBAs is economic factors (above). Yingling and colleagues have shown that, when you compare counties with low and high availability of BCBAs, you find significant differences in household income, percentage of households in poverty, and percentage of households without health insurance.

And if you think of ABA as a business, it makes perfect sense for services to exist disproportionately where they’re profitable. In general, BCBAs are scarce in rural jurisdictions where potential paying customers are scarce. If you divide U.S. counties into those with low and high access to BCBAs, you find they differ in mean population by a factor of more than 10 (low access counties = ~19,000, high access counties = ~203,000). And while access to BCBAs generally correlates with county affluence, that trend is accounted for almost entirely by high-population metropolitan areas. BCBAs tend to be scarce in rural counties regardless of local economic conditions, but in metropolitan areas BCBAs are more plentiful where residents are wealthier.

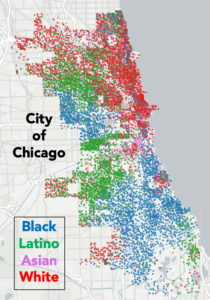

From here we can reconsider the potential racial impact of care disparities. The map at right shows the City of Chicago’s geographic concentrations of race as reported in the 2020 Census. You can see clear racial differentiation, with large concentrations of Black and Latino residents in the city’s south and west-central districts. Now check out the second map, which shows median household income, by zip code, in the City of Chicago. The darker the shading, the higher the income. In comparing the two maps, you don’t have to be a statistical genius to see that race and household income are correlated. And, by the way, you see basically the same correlation when examining median home value (a marker for generational wealth) and the percentage of adults with a college education (a marker for economic opportunity).

Given data like these, why don’t race and BCBA access appear to correlate for the nation as a whole? I’m guessing this is because “the nation as a whole” includes many rural counties where underrepresented groups are, well, underrepresented. Blacks, for instance, make up almost twice as much of the population in metropolitan areas as in rural areas. Look at metropolitan areas only, and I’m betting you’ll find clear racial disparities in access.

To get a sense of what geographic disparity looks like, let’s speculate that for-profit ABA services are disproportionately located in Chicago’s white, wealthy, northern portions of the city. If they are, then even for Latino residents of west Chicago neighborhoods and Black residents of south Chicago neighborhoods who can afford the services, the travel necessary to reach them could be prohibitive.

Here’s a non-hypothetical scenario that makes much the same point about geography and access. In my own town, income disparity correlates closely with both race and geography. My university’s training clinic is the only place in town where kids with autism can be seen for free. But even though it’s not a for-profit operation, the clinic is located on the far edge of the “white side of town,” because that’s where rental office space could be found (developers don’t tend to put up office buildings in impoverished neighborhoods). The end result is that, for many people of color, getting to the clinic requires transportation, and in my town many people of color do not own cars. That leaves city busses, which cost money and take forever to get from location to location. And, by the way, many of the clinic’s services are offered during the day when parents are likely to be working. Who can least afford to miss work? People of limited means. Unsurprisingly, the kids at our clinic are primarily white.

Cultural responsiveness concerns. As many observers have pointed out, economic and physical impediments to care equity are magnified by cultural impediments, in the sense that caregivers tend to represent the “owner class” that built the care system. For much more thoughtful commentary on this than I can offer, see articles by Luna et al. and Alai-Rosales et al. I’ll point out simply that the applied behavior analysis work force doesn’t demographically match the diversity of the U.S. population. According to the Behavior Analyst Certification Board, the overall percentage of white therapists roughly matches the percentage of whites in the U.S. population. But most of the diversity is among Registered Behavior Technicians. As mentioned above, among BCBA and BCAB-D certificants, almost 7 in 10 are white. As the Luna et al. and Alai-Rosales et al. papers discuss, a white-dominated service delivery system may not feel terribly welcoming to people of color, and without special preparation it’s unclear whether dominant-culture professionals have the culturally-responsive skill set to maximize their effectiveness in working with members of non-dominant groups.

A narrow pipeline. As Yingling and colleagues have suggested, it’s reasonable to assume that applied behavior analysts from underrepresented groups will be especially motivated to find ways to get services to the communities they represent, as well as better equipped to work with the unique cultural forces operating in those communities. This places a premium on diversifying the work force, but accomplishing that is tough because there’s a lot more involved than graduate programs being open to accepting students of color.

Consider: Prior to kids reaching school age, lingering cultural and economic sequelae of segregation create differences in pre-academic skills that have long-lasting effects once formal education begins. Kids then enter U.S. public schools that remain heavily segregated, with lower quality schools mainly offered to underrepresented groups. U.S. colleges also remain segregated, with many “general purpose” universities serving relatively few members of underrepresented groups. Should talented students of color somehow overcome those hurdles, let’s not forget that the cost of college has risen precipitously, which places a special burden on low-income students who tend to be members of underrepresented groups. To put cost into context, when I started college my tuition was $300 per year, which is less than $1800 adjusted for inflation. The current in-state tuition at the same university is about $9000 — a relative increase of over 500%. And my alma mater is at least still cheaper than many other public universities. It’s nowhere near some extremely pricey private institutions where tuition can run to $50,000 per year or more. The more expensive college becomes, the more that access will be denied to people of limited financial means.

“There Is No Try”

That’s a lot to overcome, but if we care about spreading ABA more equitably we must try. Or, more accurately, as Yoda, that fictional icon of success by a member of an underrepresented group, told us, “Do or not do. There is no try.”

Here I take some encouragement from my own university’s doctoral program in School Psychology (which by the way is just about the whitest subdiscipline in all of Psychology). Less than a decade ago that program had virtually no students from underrepresented groups. They began traveling to more-diverse campuses to educate undergraduates about the discipline and the program. This increased diversity in their application pool. In the admissions process, they stopped using the Graduate Records Exam (which is culturally biased) and de-emphasized grade point averages (which can reflect equity issues). Instead they focused more on clinical and research experience and on recommendation letters testifying to student maturity, persistence, and grit. Despite the fact that Central Illinois itself is not very diverse, today more than 1/3 of the program’s students come from underrepresented groups, and my subjective impression is that these students, who tend to be highly driven and have something to prove, exert an unusual amount of positive influence on the culture of the overall program. Many express the desire to practice in the under-served communities they came from.

Follow the money redux. Graduate school remains expensive, of course. The program described above has made progress toward diversity in part because it works hard to offer assistantships that defray student costs (I’m told that is rare in School Psychology). It seems obvious that as long as ABA training remains pricey it will benefit mainly advantaged students.

Sadly, I should point out that the financial assistance offered by my department’s School Psychology program does not represent some institution-wide initiative toward defraying the cost of graduate education. Rather, it is the result of contracts that my department has arranged with school districts and agencies that pay to have the students work for them. In truth, as I write this, some university administrators are pushing to discontinue all financial support to graduate students. They are part of a growing trend for universities to treat graduate training as a for-profit cash cow. That trend seems unlikely to promote diversity.

And of course, no matter how students get into the educational pipeline, and no matter how they manage to cover the costs, when they graduate they will enter an employment market built around ABA as a business. You can find discussions of some of the side effects of profit chasing here and here and here, but these discussions rarely delve into implications for equitable care access. Suffice it to say that if you’re an applied behavior analyst of color, and you want a well-paying position with an established agency, there’s a good chance you will find yourself serving mainly people who can afford the services. Professionals have to get paid, and communities most in need of services may not be able to afford them.

My bleak conclusion. I hope you didn’t think I was building to some genius solution. My bleak conclusion, one that I’m sure will not win me friends, is that in creating a for-profit service delivery system that benefits those with power and resources more than those without we are, in some ways, no better than those 19th Century physicians. Whatever the underlying intent of professionalizing ABA, the dominos we set into motion have not fallen equitably.

As Odessa Luna and Paulo Millán Santiago have reminded me, a great deal of contemporary inequity trickles down from societal forces that were set into motion generations ago, long before ABA existed. Unlike in the story of 19th Century maternal care, nobody in ABA can really be blamed for the existence of inequities. But benefitting from an inequitable system carries some ethical responsibility. It’s fair to ask everyone who benefits from our current system to cast off the blinders of privilege and get involved in discussions about how to make the system more equitable. Those discussions have to some degree begun: Racism and diversity and equity are starting to get a lot of attention in the ABA literature. In the latter case, it’s great that the ABA community is taking seriously the challenge of making care that is already available more culturally responsive.

I don’t, however, hear much discussion about the care that isn’t available. Data like those of Yingling and colleagues should be front and center in every conversation about diversity, equity, and inclusion in ABA. I’m all for teaching the professionals in our current system about cultural responsiveness, in order to make their services more effective. But a preliminary concern should be making those services available to all. Unfortunately, as long as the economics of ABA passively favor inequity, we’ll have inequity. There’s a social justice imperative here that should not, cannot, be ignored. I’m hoping some of you will have something to say about this. If you’re interested in writing a guest post, contact me at tscritc@ilstu.edu.

Articles about Access to BCBAs

Postscript About the Inequitable Economics of ABA

- Here’s a succinct and clear discussion in Vox about the strange, unique U.S. system in which health care is tied to employment. As we know, although certification was an important step, ABA didn’t really take off until the advent of third-party reimbursement (i.e., health insurance coverage). But health insurance is disproportionately for the privileged: people who can afford to purchase it or who get it through their employment. The economically disadvantaged and underemployed have limited, and hard to negotiate, alternatives, which leaves them with less access to AbA services. This is an example of how pre-existing, inequitable forces shape a professional system.

- Here’s an insightful article on the transformation of ABA into “therapy for the wealthy.”

Postscripts About Birthing

- One horrific consequence of maternal care shifting from midwives to physicians is that low-income women often were subjected by white physicians to “experimental treatments” with no scientific foundation and that today we recognize as likely harmful. Examples include mercury-based enemas and a “shampoo” of kerosene and ammonia. See this article that Shahla Alai-Rosales showed me about historical OBGYN abuses. Also note that, in the less-than-sterile conditions of 19th Century hospitals, bringing pregnant women into close proximity in a single ward fueled the spread of disease. For instance, in 1927 one New York hospital experienced an epidemic that killed about 1 out of every 7 women in residence — far above the prevailing maternal death rate of no more than 3%.

- Here’s a 2023 article about ongoing forces that prevent midwives from addressing maternal care disparities.

- Added 5/28/24: More on racial and gender inequities in he birthing industry.