Rats have a bad reputation. What does this have to do with Relational Frame Theory? Nothing directly, but emerging from my own peculiar derived stimulus class involving rats is a question I’d like to pose about the theory. Maybe an interested reader will answer it.

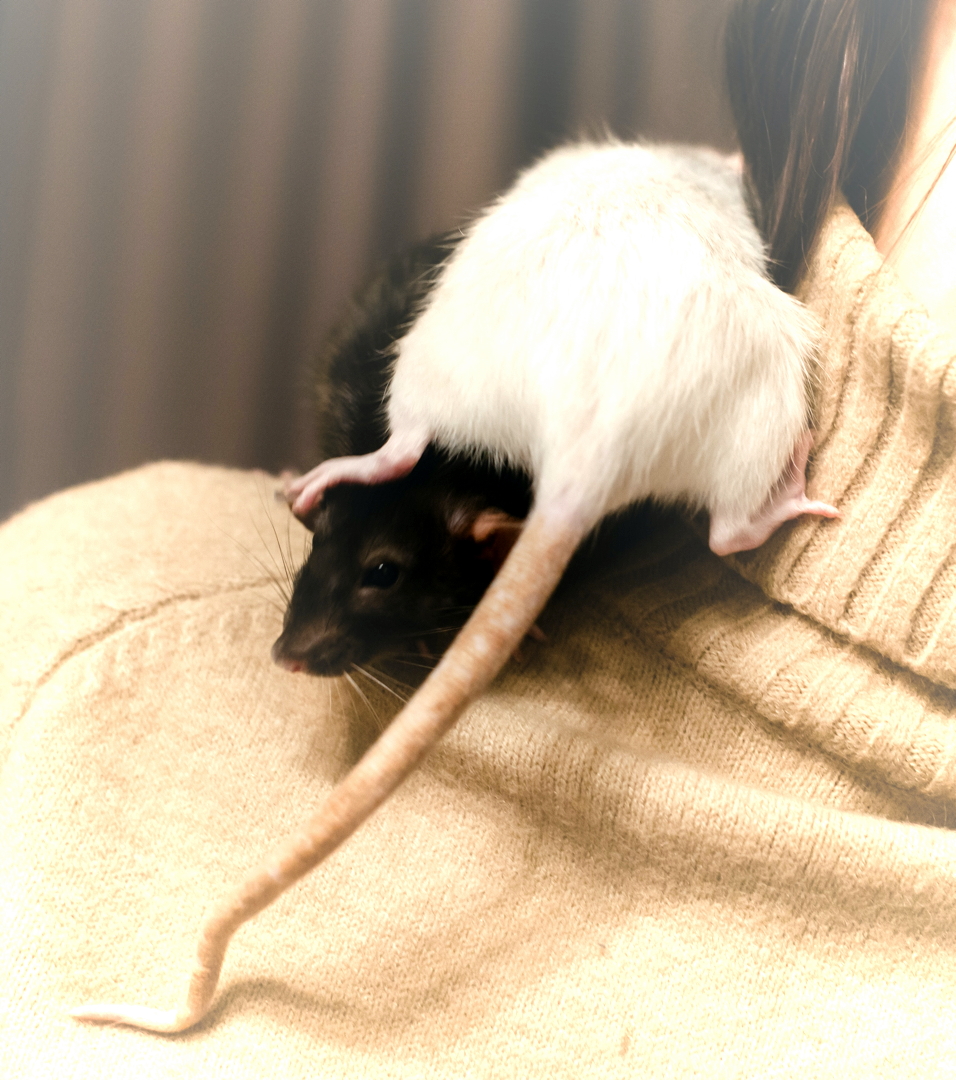

The Devil Incarnate

People are afraid of rats.

I vividly recall a sunny morning in my youth, on a farm in rural West Virginia, when I took my repose in an outhouse. Just as I was getting comfortably positioned on the throne I glanced down to see a big old country rat perched right next to my foot. I lost it, and a second later — imagine this or not, it’s up to you — I was sprinting across the meadow with my pants around my ankles, spewing unintelligible yawps of terror.

Musophobia, fear of rats and mice, is the 6th most common specific phobia (about 9% of the population). But many people have a strong non-clinical rat aversion. This is so common that rats are a favorite trope of horror films, and you can find numerous lists of the “best” rat-themed scary movies. Inevitably in these films, rats-run-amok rise up to slaughter poor innocent humans.

But there are, of course, nonfictional reasons to be wary of rats. They have those nasty looking tails, and they are, by nature, creepy-crawly things in the dark. They steal crops and raid food larders. They can carry disease and have been blamed for Europe’s all-time deadliest plague. As an invasive species, they are the #1 cause (aside from humans, duh) of native-species extinctions.

Rats also have been implicated in some icky stuff that isn’t entirely their fault. For instance, check out this episode of the TV show Fear Factor. And, I kid you not, there is something called rat torture (which does not involve coercing rat spies to divulge state secrets). Honestly, I don’t even want to talk about this. Look it up for yourself.

Suffice it to say that in the popular imagination rats are Pure Evil.

Not So Bad After All

However, I refer you to a lovely recent piece by J.D. Mackinnon in Hakai magazine, which urges a more balanced and realistic appraisal of rat-dom on the grounds that many rat sterotypes are false or overblown. Turns out, for instance, that rats are less likely to carry disease, and more sanitary, than most people think.

Sure, we behavior analysts appreciate rats on a certain level. After all, tracing back to Skinner’s Behavior of Organisms, we’ve made them a cornerstone of basic behavioral research and for this reason, though we might not admit this to clients, without rats there would be no applied behavior analysis. But when we think of similarities between rat and human behavior we tend to think of nuts and bolts stuff like reinforcement schedule effects, extinction, and stimulus control.

Mackinnon’s effort at repairing the rat’s image focuses on social behavior. Rats are social animals that, unlike the attack rats of film, become aggressive only under unusual circumstances. Anyone fortunate enough to take a rat lab class (fewer and fewer these days, sadly) knows that rats are easily tamed. Properly socialized rats seem to get a lot of enjoyment out of interacting with people. And properly socialized people seem to get enjoyment out of interacting with rats; Mackinnon’s article mentions a veterinarian advising people who think they want a small dog to instead get a rat.

What may be less familiar to behavior analysts is how rats treat rats. Pretty decently, actually. Rats reliably show evidence of both “altruism” and “empathy” toward other rats [see this review of the rat empathy literature by Cox and Reichel (2021)]. Many experiments show, for instance, that rats will devote effort to releasing another rat from an unpleasant situation (e.g., confinement, exposure to painful stimuli, etc.). In other words, freeing the other rat functions as a reinforcer. When placed together with a conspecific that has just experienced pain, rats will engage in behaviors, like paw licking, that members of their species commonly emit when in pain. Rats viewing a conspecific in pain experience measurable hyperalgesia (that is, the observer rat feels pain more intensely). And so on.

Empathy and Uncertainty

Based on this kind of evidence it might be said that a rat can say, er, demonstrate, “I feel your pain.” If we take the evidence at face value (there’s room for debate about that), it raises interesting questions about the nature of human empathy. Loosely speaking, empathy is defined as the ability to take another’s perspective or, to put it a bit more behaviorally, acting in a way that suggests you perceive and care about another’s situation (I am oversimplifying here; perspective taking may be complicated).

The best-developed behavioral theoretical account of empathy comes out of Relational Frame Theory — here’s a short and accessible introduction to that account. The gist is that empathy or perspective taking is said to consist of three types of “deictic” stimulus relations, I-YOU, HERE-THERE, AND NOW-THEN. While I is different from YOU, HERE is different from THERE, and NOW is different from THEN, empathy occurs when YOU, in the THERE and THEN, acquires a degree of equivalence with I in the HERE and NOW. There is promising research indicating that teaching deictic relations can improve perspective taking (see

as well), but the outcomes are not always squeaky clean and much remains to be learned. For present purposes, though, I’m more concerned with the underlying theoretical account.

The foundation of all RFT is two core assumptions: (1) Pretty much anything important humans do runs through derived stimulus relations, and (2) All derived stimulus relations are inherently verbal. By default, therefore, empathy, if it depends on deictic relations, is a verbal process. But if that is true, how might rats arrive at behavioral performances that suggest some semblance of empathy? Based on blind logic I can think of these possibilities.

- All empathy is verbal. Nope. Not buying that rats have stealth verbal capabilities.

- All empathy is nonverbal. Also a nope. The effectiveness of verbal deictic training protocols suggests otherwise (though see #4 below).

- Rat empathy is nonverbal and human empathy is verbal. That is, different processes yield topographically similar behavioral outcomes. Not implausible, but in light of a long and sometimes silly scientific history of automatically assuming humans to be special — this has been one basis for rejecting operant processes as relevant to humans — I’m skeptical about this one.

- Both rat empathy and human empathy both have nonverbal roots, which in humans can be supplemented by verbal processes. Here we can find a lot to work with. Evidence suggests that at least some of the neural architecture involved in empathy lies in nonverbal areas of the brain, which would fit with the notion that all empathy is at least partly nonverbal. In the empathy literature it’s also common to assume that empathy subsumes multiple processes that may differ in the degree to which they are “cognitive” (verbal?). As for RFT itself, as a general approach it leans heavily into the potential interactions between verbal and nonverbal processes. For instance, the theory (as extended into Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) often is used to explain human problems in which verbal rules interfere with presumably nonverbal “values” (that is, people’s Big Reinforcers).

And yet there is room for uncertainty. RFT always refers only to homo sapiens, which it considers an inherently verbal species, so perhaps it’s unsurprising that I’m aware of no RFT discussion that explicitly tackles the problem of interspecies generality. Specifically I’m aware of no RFT-focused discussion that talks about potential nonverbal roots of empathy. Most generally, I’ve always had a nagging feeling that RFT is a bit vague on how verbal and nonverbal behavior intermingle in the same organism (except, of course, for those instances where the two clash and create harm). It doesn’t seem to have a lot to say about the potential for evolutionary conservation of psychological processes, or about the possibility that verbal behavior may sometimes be ancillary to nonverbal processes.

A historical perspective may suggest why this is so. RFT was originally introduced, and marketed if you will, as the “post Skinnerian” alternative to traditional Skinnerian behavior analysis. Perhaps since then a bit too much effort has been put into explaining how RFT is different, and not enough into explaining how it builds upon everything behavior analysis established prior to the early 2000s. Maybe the discussion has focused too much on when humans behave verbally and not enough on the possibility of nonverbal processes sometimes predominating (for a stimulating discussion on this point that’s rather specific to the topic of empathy, see Taylor and Edwards, 2021). If I’m right, and there’s a gap in the theory, that’s no criticism. Theory development is a long slog (just ask physicists!) and we might simply be discussing an opportunity to better explore how and whether RFT can be a general purpose theory of behavior rather than a theory of when one species relies heavily on one kind of behavior.

But maybe I’m just wrong. I’m a fan of RFT and believe everyone needs to learn about it (e.g., see my chapter with Ruth Anne Rehfeldt in the ABA “White Book,” 3rd edition). But I’m not an RFT insider, and I haven’t read everything there is to read. So maybe what I want to know is already laid out somewhere. If so, I’m hoping someone in the know will step up and explain it to us in a future post. If that’s you, let me know at tscritc@ilstu.edu.