Here are two core facts of the science of behavior: Response rate (a) tends to increase under reinforcement, and (b) specifically does so when behavior control shifts from continuous reinforcement to most forms of intermittent reinforcement. These effects have been demonstrated in too many studies to count. Imagine the surprise of Pliskoff and Gollub (1974), then, when one of their subjects appeared to break the laws of behavior.

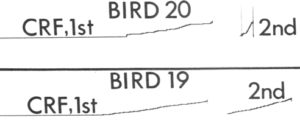

Two hungry pigeons, dubbed S19 and S20 in the published article, but let’s called them Bonnie and Clyde for the lawlessness soon to be described, acquired a key-pecking response after being placed into an operant chamber with a key peck producing food reinforcement on a continuous reinforcement schedule. That they started key-pecking was unsurprising: Pecking is a high probability pigeon behavior, so sooner or later they are likely to peck just about anything in their line of sight. Once Bonnie and Clyde pecked the key and reinforcement followed — this took a bit, as shown in the flat left side of the cumulative records marked “CRF 1st” — it was just a matter of time before response rates started to climb. The cumulative records in the figure (left side) shows that both Bonnie and Clyde took quite a while to get around to that first peck, but thereafter began to depress the key reliably.

Notice especially the 2nd session, where Clyde’s rate took off, but Bonnie’s rate (S19) was unchanged from the 1st session. Bonnie was given two extra sessions on continuous reinforcement, but to no avail. Then the schedule was shifted to variable interval, to limited effect. Then the size of the reinforcer was increased, again to limited effect. No matter what was tried, Bonnie’s response rate remained tepid.

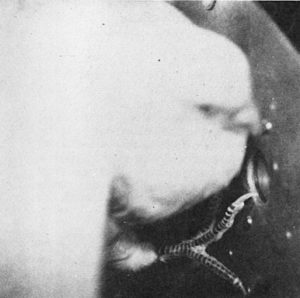

By this time, Pliskoff and Gollub (1974) wrote, “S19 was a prime topic of conversation between the authors and anyone else who would listen. The lesson seemed quite simple: S19 had its own set of behavioral laws.” But eventually a wise member of the research team decided to bypass the intricate data records of the cumulative recorder and peep into the operant chamber during one of Bonnie’s sessions. The photo shows what was observed: Bonnie had not been key-pecking at all!

For some peculiar and inscrutable reason, Bonnie was “pressing” the key, rather than pecking it, but in a most colorful way. She would stand at the rear of the chamber, leap into the air with wings fluttering and head bent to avoid the ceiling, and strike the key with her foot. Many of these “flying kick” responses were poorly aimed and missed the mark, but [the photo] shows a successful one.

When reinforcement doesn’t depend on any particular behavior topography, it tends to follow, and thereby gain control over, high probability responses and/or those involving minimal response effort. However, no law of nature makes this the required outcome. Place 1000 pigeons in Pliskoff and Gollub’s (1974) acquisition procedure, and perhaps 999 of them will start pecking. But in a rare case, any other action that depresses the key and delivers reinforcement might instead be strengthened. Bonnie’s response rate never increased because the topography that got strengthened can only be performed so fast — it takes time to flutter toward the response panel, kung-fu kick at the key, and then dust yourself off and begin the process anew. But this behavior pattern maintained because it worked “well enough.” Once established, it got reinforced sufficiently often to crowd out other types of potential key-depressing responses.

Effects like these are not limited to bird brains. In an experiment that required humans to press four large buttons on a console, I once had a participant press them with her elbow, rather than her fingers. Rather than remain comfortably seated before the console, she spent whole sessions hunched over it in a half crouch, playing a bizarre version of whack-a-mole in which she forcefully jammed her right elbow down on the buttons. I became aware of this only when she informed me she was leaving the study due to elbow pain. To be honest, I had heard the sounds of forceful “button presses” coming out of the subject room. And I had noticed that this participant was a bit of a slow worker. But somehow, unlike Pliskoff and Gollub (1974), I never thought to peek inside the work room. Had I done so, considerable time and effort, not to mention joint pain, might have been saved. By the way, when asked why she chose to use her elbows, my human Bonnie replied, “You never told me to use my hands.”

Inside the operant laboratory, procedures have been worked out so thoroughly, and are so reliable, that we do not expect oddities like these. Outside the laboratory, however, the notion that remarkable response topographies may be selected by unremarkable contingencies is far from novel. This is the entire premise behind functional behavioral assessment, which “diagnoses” the reinforcer responsible for dramatic behaviors like tantrums, physical aggression, psychosomatic symptoms, self-injury, delusional speech, and more. In a vast number of cases, these unusual behaviors turn out to be reinforced by nothing particularly unusual. Speaking loosely, they may be atypical substitutes for mundane behaviors like asking for something you want, asking to stop doing something unpleasant, and getting someone’s attention. Unlike with Bonnie, it may not always be possible to reconstruct how these behaviors became selected over more socially accepted alternatives, but the take-home message is the same as that derived by Pliskoff and Gollub (1974), who acknowledged; “We did, by the way, conclude that the organism is always right.”

Note: The cumulative records and photograph shown here are reproduced from Figures 1 and 2, respectively, of the following article.

Pliskoff, S. S., & Gollub, L. R. (1974). Confidence lost and found, or, is the organism always right?. The Psychological Record, 24, 507-509.