By Nicole Gravina, Ph.D. and Jessica Nastasi, M.A., BCBA

After years of coaching people in business, we have learned that effective leaders are also effective time managers. Successful leadership strategies (e.g., work sampling, feedback, training) require time from a leader, and if the leader does not have the time available, they miss opportunities to use them. Poor time management is also correlated with higher levels of perceived stress, burnout, poor relationships, and other adverse outcomes (Hafner & Stock, 2010; Haffner et al., 2014; Nonis & Sager, 2013; Peeters & Rutte, 2005).

When we say time management, we do not mean completing a certain amount of tasks during a specific time period. We mean choosing to use our available time purposefully, consistent with our goals and values.

We want to acknowledge that life presents many time management challenges. The first author dramatically changed the way she managed her time after having kids, and again at the onset of COVID-19. After the initial upheaval felt from those life events, employing time management strategies helped her find her footing. As a doctoral student, the second author has worked to stay productive and find time for self-care. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that we possess a set of privileges that allow us the space to make these changes, and that others may face additional barriers to managing their time while also taking care of themselves and their loved ones. We hope that these ideas are useful for individuals who are in a position to employ them.

Time management is an ongoing effort to actively balance demands, goals, and values from each domain of our life. It requires continued attention and adjustment as our context changes.

To help leaders understand why time management is imperative, we do an exercise we call Manager A/Manager B. Manager A is a highly effective and well-like manager and when asked to list how Manager A achieves those outcomes, people list several behaviors such as asking questions, setting clear expectations, and providing feedback. Manager B is an ineffective manager and is disliked by the team and when we ask people to list behaviors Manager B engages in to achieve those outcomes, at least half of the list is a lack of behavior (e.g., never available, no feedback, lack of communication). This exercise drives home the point that if a leader is not taking the time to be Manager A, they are probably Manager B.

So where should a leader start to become a better time manager? Below we have listed a few tips we provide when supporting leaders working toward improving their time management skills.

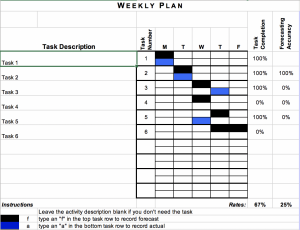

Forecasting

When it comes to time management, we can forecast: what we will accomplish, when, and how long it will take. If we can forecast accurately, we can plan accurately. Most people underestimate how long tasks will take and do not account for unexpected events that arise during their week. We can get better at forecasting with practice. Write down 5-10 tasks you plan to complete this week, how long they will take, and when you will do them. Then, take data on whether you completed them, how long they took, and when you did them, and calculate the accuracy of your predictions. Over time, you will become more effective at accurately predicting the time tasks require, and plan accordingly.

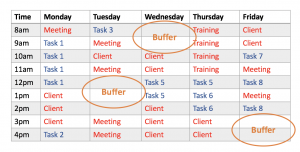

Buffer Time

For most leaders, unexpected events arise each week and if their schedule is fully booked, they must cancel or move calendar items to address these events. But, we can plan unexpected activities into our schedules before we know about them. While you are taking data on forecasting, also take data on how much time you spend addressing unexpected events each week. Then, block off time in your calendar to address these events. If no unexpected events occur that week, great! Refer to your to do list and accomplish a few extra tasks. Creating space for unexpected events will allow you to realistically plan your week and prevent unexpected events from derailing your other scheduled meetings and tasks.

Meeting Audit

Most organizations add meetings while failing to remove others. This is how some leaders end up with 80% of their time spent in meetings. Bring your team together for a meeting audit to reduce the time spent in meetings. Removing just one 1-hr meeting from your calendar each week aggregates to a week of work time regained. Here are the questions to ask during a meeting audit:

Is this meeting necessary?

Does everyone need to be there?

Can it be shorter?

Can it be every other week?

We also recommend ending all meetings 10 min early to allow for transition time to the next meeting. This can help subsequent meetings start on time (Fineup et al., 2013).

Email Management

Most leaders estimate that they spend approximately two hours per day reading and responding to email. They also admit to checking emails as they arrive in their inbox. To reduce the time spent on email, we suggest designating specific times to check and respond to it. It could be a half-hour in the morning and a half-hour at the end of the day. It could be the last few minutes of every hour. Regardless of the schedule you decide, turn it off when you are not checking it to avoid derailing progress on other tasks. Also, when checking email, triage. Emails that require short responses can be responded to right away; others can be immediately moved to a file or deleted. If an email requires a longer response, wait until you have a longer designated time (e.g., end of day) to respond. Finally, some interactions would be more efficient if we discussed the issue in a 5 min phone conversation instead. Do your best to move email discussions to quick phone chats, which have the bonus of reducing miscommunication and improving rapport (Connell et al., 2001).

Plate Spin

Plate spinning is a common technique in sales. To manage sales, salespeople keep a list of prospects and touch base with them every few months. We think this can be easily adapted to client, research, and project management. The first author plate spins the research projects in her lab. Some projects require regular attention and others are in more passive phases (e.g., under review). The list reminds her to give each project attention and it is also a source of ideas for her to do list. Additionally, a plate spin list serves as a quick reference for monitoring research progress and student activities. The list can be in a document, a digital “sticky”, on a white board, or on paper. We prefer low effort solutions to more complex ones, because we are usually more likely to use and maintain them.

Saying No

We mentioned earlier that time management means using time purposefully. Sometimes, to stay focused on our most important tasks, we have to say no to others. Saying no does not have to mean that the task does not get completed. We could delegate it, we could reimagine it in a way that requires less time and effort, or we could delay it. Saying “no” is easier once we have identified the activities that bring the most value to our work and lives. Setting clear boundaries with our time is necessary to take care of ourselves, our families, our team, and our work. If you have too much on your plate at work, we suggest that you make a list of all of your required duties. Then, rank order those duties in terms of the value they add to the organization and whether you are the person with the best skill set to complete those tasks. Ask yourself:

Is this task really necessary?

Does this task need to take this much time or occur this often?

Can someone else do this task?

Can this task be delayed?

These are just a few of the exercises we suggest to leaders working on improving their time management. We believe time management is a journey and the skills and strategies that work for you now, might need adaptation when your job or life circumstances change in the future. Using time management strategies can help us endure the more challenging times, and thrive once they pass.

References

Bond, M. J., & Feather, N. T. (1988). Some correlates of structure and purpose in the use of time. Journal of personality and social psychology, 55(2), 321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.2.321

Connell, J. B., Mendelsohn, G. A., Robins, R. W., & Canny, J. (2001, September). Effects of communication medium on interpersonal perceptions. In Proceedings of the 2001 International ACM SIGGROUP Conference on Supporting Group Work (pp. 117-124). https://doi.org/10.1145/500286.500305

Fineup, D., Luiselli, J., Joy, M., Smyth, D., & Stein, R. (2013). Functional assessment and intervention for organizational behavior change: Improving the timeliness of staff meetings at a human service organization. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 33, 252-262. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2013.843435

Häfner, A., & Stock, A. (2010). Time management training and perceived control of time at work. The Journal of Psychology, 144(5), 429-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.496647

Häfner, A., Stock, A., Pinneker, L., & Ströhle, S. (2014). Stress prevention through a time management training intervention: An experimental study. Educational Psychology, 34(3), 403-416. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.785065

Nonis, S. A., & Sager, J. K. (2003). Coping strategy profiles used by salespeople: Their relationships with personal characteristics and work outcomes. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 23(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2003.10748994

Peeters, M. A. G., & Rutte, C. G. (2005). Time Management Behavior as a Moderator for the Job Demand-Control Interaction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(1), 64-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.1.64