Verbal Apparitions

Guest Blog by: Lee Mason, PhD, BCBA-D

Child Study Center – Cook Children’s, Fort Worth TX

While the holiday season is meant to bring feelings of love and cheer, for many it is also a time of pain and sorrow. There are many ways to combat such holiday stress, including exercise and eggnog. Or perhaps you prefer to escape by picking up a good book. Not a schoolbook. Not an assigned journal article. But something you read purely for the joy of reading it. So let me ask you as you read this: What maintains reading behavior? Your early phonemic awareness and decoding was likely reinforced by teachers and parents. Undoubtedly, comprehension continues to serve as a reinforcer in the presence of textual stimuli. Academic readings may be socially reinforced through class discussions. But what reinforces reading for leisure? Books that are entirely self-serving and unlikely to be discussed with your friends or anyone else. The kinds of readings in which you might even be embarrassed to admit that you take pleasure. At least in times of stress, it might be to escape your current surroundings.

“Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.” – Harper Lee

For me, picking up a book by Joe R Lansdale instantly transports me to East Texas, where I held my first teaching position. I can still smell the pine trees and feel the heat of the Texas sun. Similarly, reading Andrew Vachss teleports me to New York City, where I’ve never been, but from my other experiences in large cities, I can smell the streets and hear the commotion of the large urban surroundings. Perhaps you’re more into Ron Chernow, whose books allow you to travel through time to experience the environmental conditions that led to the American Civil War. Or maybe you prefer Philip K Dick, who allows you to speculate about what the future might hold.

Regardless of what you read for leisure, our tendency to read is probably maintained by the sensory perceptions that have come under the control of verbal stimuli. Like all operant behavior, verbal behavior operates on the environment. What makes verbal behavior unique is the manner in which it functions to modulate space and time. Verbal behavior allows us to order pizzas from across a city or relive the excitement of last week’s sporting event. But for as much good as a complex verbal repertoire can do for us, it may also be the root of that holiday stress you’re feeling right now. Perhaps you’re experiencing the first holiday without a loved one. Or maybe you can still hear the scathing words of a family member that were spoken years ago.

“A book is a dream you hold in your hands.” – Neil Gaiman

The same controlling relations that allow us to get lost in a good book may also serve to trap us in perceptual responding. So let us turn to literature to examine how perceiving comes under the control of verbal stimuli, and explore the notion of mental health with a few notable examples.

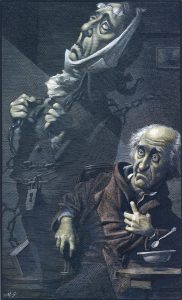

One of the most famous literary psychotic breaks of the holiday season can be found in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843), in which Ebenezer Scrooge is visited by the ghosts of Christmases past, present, and future.

Many of us overlook the mental health disparity of Scrooge, because we’re pleased with how the story works out for Bob Cratchit and family. But do you ever wonder what subsequently happened to old Ebenezer? Did his ghosts ever return? To better understand this, we must first understand where his ghosts came from, and of what they exist.

Our modern idea of ghosts originated from the primitive technology of Victorian era photography, with exposure times of up to 15 min in duration. (Hold that smile!) If the subject left before the shot was finished, the result was a spooky afterimage. But these kinds of ghosts typically only haunt young children and movie goers. The horror of Ebenezer’s visitors had less to do with their incorporeal being than the history of reinforcement from which they emerged.

So how do we account for seeing in the absence of the thing seen? Says Skinner (1974), “Current stimulation is then minimally in control, and a person’s history and resulting states of deprivation and emotion get their chance” (p. 94). While for many of us, the holidays are a cheerful time away from work to spend with friends and family, for Mr. Scrooge, work provided an important social reinforcer that kept aversive stimuli at bay (i.e., memories of the termination of his engagement to Belle, and the passing of his business partner Jacob Marley). Without current sources of stimulation to compete, Scrooge became lost in the echoes of his own history. Notably, Ebenezer never feared his apparitions; what terrified him were the equivalence formations of his past, present, and future self!

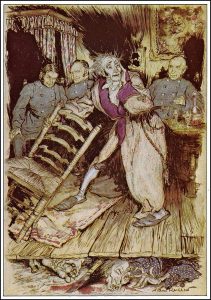

But what, you may ask, is out of proportion? The classic exemplar of disproportionality comes from Poe’s (1843) The Tell-Tale Heart. We typically attribute hauntings to the work of the deceased. But here, the unnamed narrator is haunted by a living old man with whom he shares an apartment. Specifically, it is the old man’s vulture eye from which the narrator cannot escape. Void of competing sources of stimulation, the eye appears to follow him everywhere. Later on, after disposing of the source of his prepotent stimulation, he cannot stop the beating of the old man’s hideous heart!

Once again, Skinner describes this as perceptual behavior, explaining that, “After hearing a piece of music several times, a person may hear it when it is not being played…. he is simply doing in the absence of the music some of the things he did in its presence” (1974, p. 91). But perhaps nobody says it better than Richard Matheson’s Chris Neal (Mad House, 1953), who – unsettled by his own environmental history – proclaims, “With words I have knit my shroud and will bury myself therein.”

“The reading of all good books is like a conversation with the finest minds of past centuries.” – Rene Descartes

While much of this post has been focused on the disproportionate allocation of time to perceptual behavior, we are also fortunate that verbal behavior allows us to be influenced by voices of the past. In 2019 we lost a number of great behavior analysts, including Murray Sidman, Barbara Etzel, Bill Timberlake, Janet Ellis, and Chuck Merbitz among others. If you ever received an email from Chuck, you may have noticed his signature line which read:

While much of this post has been focused on the disproportionate allocation of time to perceptual behavior, we are also fortunate that verbal behavior allows us to be influenced by voices of the past. In 2019 we lost a number of great behavior analysts, including Murray Sidman, Barbara Etzel, Bill Timberlake, Janet Ellis, and Chuck Merbitz among others. If you ever received an email from Chuck, you may have noticed his signature line which read:

“The most important thing in life is to pick your reinforcers.” B.F. Skinner 1951, as quoted by O. R. Lindsley.

Among the many things for which we have to be grateful this holiday season, allocate some time to reflect on the reinforcers that matter most to you. If this includes a favorite book, take note of how the words on a page function to alter your immediate environmental surroundings; or how noncurrent events function to pull you away from those words on a page.

*Note: If you or someone you know is suicidal or in emotional distress, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Lee Mason, PhD, is a licensed behavior analysts with Child Study Center, Cook Children’s Health Care System, and affiliated faculty with Texas Christian University’s ANSERS Institute. His research interests include verbal behavior assessment and transfer of stimulus control. He has served on the boards of the Texas Association for Behavior Analysis and the American Council on Rural Special Education.

Lee Mason, PhD, is a licensed behavior analysts with Child Study Center, Cook Children’s Health Care System, and affiliated faculty with Texas Christian University’s ANSERS Institute. His research interests include verbal behavior assessment and transfer of stimulus control. He has served on the boards of the Texas Association for Behavior Analysis and the American Council on Rural Special Education.