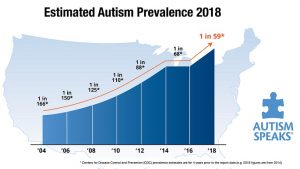

The CDC recently released an updated prevalence estimate of ASD among the children in the United States (full report can be found here).

Despite this increase in the number of individuals diagnosed, many are not diagnosed until the age of four or do not have access to behavioral services. This can be disheartening in light of data supporting the benefits of early behavioral intervention. Instead of letting this information cast a gloomy shadow, we should see it as an opportunity. See it as an invitation to do more.

What can we do?

Early diagnosis

Given the known benefits of early intervention, researchers from a range of different fields are interested in learning more about ASD in infants with the aim of decreasing the average age of diagnosis. It has been well established there are differences in brain structure of individuals with autism and infants at high risk for ASD. Further, researchers have uncovered genetic markers of ASD, suggesting a strong hereditary component. As a result of these scientific efforts, it is possible to pinpoint early biological markers of ASD. Doing so, however, can be costly and many will likely not reap the benefits of these methods for early diagnosis for many years to come. Behavioral assessments and screening tools, however, can be more easily implemented.

Existing diagnostic tools are not normalized with children younger than 24 months old (e.g., ADOS), but it is possible to screen children based on observable, measurable signs of concern. In infants, these signs include lack of age appropriate sounds, unusual repetitive behaviors, lack of age appropriate social interactions, among others. Caregivers are often keen observers of their child’s development and can provide useful information when screening for social-developmental delays. Caregiver concerns of behavioral markers for children between 12-18 months of age have been found to be predictive of a future ASD diagnosis. Further, caregivers can more accurately identify and differentiate children with ASD-related concerns.

Existing diagnostic tools are not normalized with children younger than 24 months old (e.g., ADOS), but it is possible to screen children based on observable, measurable signs of concern. In infants, these signs include lack of age appropriate sounds, unusual repetitive behaviors, lack of age appropriate social interactions, among others. Caregivers are often keen observers of their child’s development and can provide useful information when screening for social-developmental delays. Caregiver concerns of behavioral markers for children between 12-18 months of age have been found to be predictive of a future ASD diagnosis. Further, caregivers can more accurately identify and differentiate children with ASD-related concerns.

Dr. Maurice Feldman and colleagues developed a behavioral screening tool, Parent Observation of Early Markers Scale (POEMS), for caregivers to report early markers of ASD in infants ages 1-24 months old. In our clinic, we have successfully used the POEMS to identify early warning signs of ASD in infants at high-risk for ASD diagnosis (e.g., younger sibling of child with ASD).

In your clinical practice, do you have systems in place for early identification of warning signs in infants? How could we collaborate with other providers (e.g., pediatricians) to ensure more children are properly screened at an early age?

In your research endeavors, how could we refine our screening methods? Could we work with researchers from other fields to establish well-validated behavioral and biological early markers of ASD?

Early, early intervention

On average, children are diagnosed with ASD at the age of four. Thus, the majority may not have access to early intensive behavioral interventions at the ideal time (i.e., before the age of four to five). Ideally, children should start receiving services to address delays as soon as these are detected, even if an ASD diagnosis has not been rendered. Researchers and practitioners have been exploring interventions for very young children at risk for ASD, with the aim of increasing early social skills.

Dr. Sally Rogers at UC Davis has evaluated interventions for ameliorating warning signs in 6-month-old infants. Dr. Martha Pelaez has studied interventions focused on the mother-infant interactions with children at risk of language delays and developmental and learning problems. Her work has been presented at the Florida Association for Behavior Analysis and the most recent ABAI Annual Autism Conference. If you work with infants and toddlers are not familiar with Dr. Pelaez’s work, I highly encourage you to do so.

Others (ourselves included) have focused on coaching caregivers to implement protocols aimed at developing early social skills in infants and toddlers. Just like caregivers are ideal observers of their child’s delays and warning signs, they are also in an ideal position to positively impact their child’s behavior.

In your clinical practice, how do you work with very young children diagnosed with ASD? What role does caregiver training play in your work with very young children with ASD?

In your research endeavors, have you evaluated protocols for early, early intervention? What teaching strategies work best with very young children?

Telehealth services

Telehealth services

Although the number of behavior analysts is steadily rising, many individuals do not have access to behavioral services as a result of geographical or financial barriers. Luckily, technology can help circumvent some of these barriers, allowing us to provide services more broadly.

Telehealth has been used to train staff to conduct preference assessments, train caregivers to conduct functional analyses, train novice therapists to conduct discrete trial training, and train staff to improve the verbalizations of their clients, among others. This recent interest in telehealth services has led various large facilities providing behavioral services to individuals with ASD to launch such services (e.g., Marcus Autism Center, Munroe-Meyer Institute, Scott Center for Autism Treatment).

Is telehealth an alternative in your community? What remains to be understood about the usefulness of telehealth for delivering effective behavioral interventions? Are there ethical or service quality concerns regarding the use of telehealth?

Autism prevalence rates are rising. In this post, I barely scratched the surface of what is possible for behavior analysts to do regarding young children with ASD. But what about adolescents and adults? After all, this increase in number of children diagnosed will also result in increased need for services for older individuals. How can we, as behavior analysts and behavioral scientists, contribute?

Follow the

Follow the